Percy Sledge’s song When a Man Loves a Woman touched enough people to make it a number-one song in 1966. Next, compare the feeling of love in Sledge’s song with that of Odysseus in Homer’s epic the Odyssey. The eponymous hero doesn’t want to fly. When the beautiful goddess Calypso tries to keep him as her bedmate, he turns her down even though she promises him immortality – a place with the gods. He wants to go home to his wife. Before Ekman and Friesen, love had most certainly been considered an emotion. Indeed, the two psychologists were bucking a long tradition that made love not only an emotion but sometimes also the premier emotion. In the 4th century BCE, love was one of 12 passions named by Aristotle (though he knew that he was leaving out many others). In the 13th century CE, Thomas Aquinas made love the prime mover of every emotion. And in the 1960s, Magda Arnold, a pioneer of cognitivism, classified love as a positive ‘impulse’ emotion. For all of these theorists, love was paradigmatic of all the other emotions. Percy Sledge’s inability to think about anything but his girl tapped into a Western tradition of very long-standing: love as an obsession. It means coveting, admiring, desiring and being frustrated.

Saturday, August 20, 2022

Love and Tragedy: The Hustler by Robert Rossen

Researchers from Harvard Chan SHINE and the Human Flourishing Program have published a new paper in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology (August, 2, 2022) exploring the role of strengths of moral character and love in mental health. Authors Dorota Weziak-Bialowolska, Matthew T. Lee, Piotr Bialowolski, Ying Chen, Tyler J. VanderWeele, and Eileen McNeely used longitudinal observational data. “Our findings show that persons who live their life according to high moral standards have substantially lower odds of depression.” —Dorota Weziak-Bialowolska concluded.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, obsessive love’s narrative became darker. In Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), the eponymous hero is hopelessly in love with Lotte. He constantly thinks how, if only she were with him, he would cover her with kisses. He never stops wearing the outfit that he wore at their first meeting and, when it wears out, he gets another that is identical. Lotte is everywhere in his imagination. He loves her ‘solely, with such passion and so completely’ that he knows nothing except her. He measures up because he loves. He’s glad to be miserable. When he kills himself, it is because one must go to any length for love. Romantic profundity is not merely about duration, it is also about complexity. An analogy can be found in music. In 1987, William Gaver and George Mandler, psychologists from the University of California, San Diego, found that the frequency of listening to a certain kind of music increases the preference for it. As with music, so it is with love. The complexity of the beloved is an important factor in determining whether love will be more or less profound as time goes on: a complex psychological personality is more likely to generate profound romantic love in a partner, while even the most intense sexual desire can die away. Source: aeon.co

“Happiness in marriage is not something that just happens. A good marriage must be created. In the art of marriage, the little things are the big things. It's never being too old to hold hands. It's remembering to say 'I love you' at least once a day. It's never going to sleep angry. It's at no time taking the other for granted; the courtship should not end with that honeymoon, it should continue through all the years. It is havig a mutual sensue of values. It is standing together facing the world. It is not looking for perfection in each other. It is cultivating flexibility and a sense of unity and patience. It is doing things for each other not in the attitude of duty or sacrifice but in the spirit of joy. It is having the capacity to forgive and forget. It is finding room for the things of the spirit. It is a common search for the good and the beautiful. It is not marrying the right partner, it’s being the right partner.” – Excerpt from Paul and Joanne’s vow renewal letter.

Robert Rossen came to another performance of our play, and this time he came backstage and was introduced to me by my agent. He was dressed very casually and seemed a little nervous holding the script that he presented to me. “I saw you in the plays at the Actors Studio,” he told me. “I’ve written something I’d like you to read.” My agent Bob Richards thought this approach was a waste of time, but I persisted. I thought of all the hours the writer had spent, and I felt I owed them more than a hasty read. Rossen’s script was called The Hustler. My character, Sarah, didn’t enter till about page forty, but around page five I already knew I wanted to be in this movie. The script was so clean and strong, and I was excited. I had never before read a script where I could so vividly feel the characters and rooms. I could pour myself into it and disappear. I told my agent right away that I wanted to do it. Thank God, Rossen had been patient. We agreed to meet. He came up to my empty apartment, where the living room now had a chair in addition to the daybed, and we talked a little about this mysterious girl, Sarah Packard. Who she really was. I thought I understood her, even if I didn’t know the particulars, the truth about her background. Rossen told me Sarah was sort of a fallen woman, and a romantic at heart. The film was being produced by 20th Century-Fox. The studio had wanted Anne Francis to play the part. They finally relented and agreed to sign me but wouldn’t move above a certain figure. My agents and I stood firm on $40,000—not a princely sum, but a fair one for the time. Rossen took a stand on my behalf and insisted on my playing the role and their paying me the $40,000. The studio finally agreed.

Rossen felt he couldn’t speak to an actor about what he wanted for a particular moment or scene in terms “useful to the actor,” though he knew it when he saw it. If it rang true to him, he’d record. I’d done Until They Sail with Paul Newman two years before at MGM, but on that film there had never been an occasion for me to be close to him. Lifting my head from the script to speak my first line to Paul, I was met with the blinding force of his unearthly blue eyes. It was more than the eyes; it was also of course the mouth, and the unbelievable grace of his cheekbones. Almost two weeks passed before I could do my work and just see a man acting his part. Working with Paul was a joy from the beginning. I’m sure he was unaware of the effect his beauty had on people. He was very serious about the work, often thinking he wasn’t good enough. But outside the work, he was generally easygoing and quite down to earth. When I arrived every morning, I would see Paul reading a newspaper in the makeup room. Up to that time, he was the only actor I had ever seen doing that. Not many actors read anything but the trade papers or their script that early in the morning. It surprised me because generally Paul made an effort to come off as cool and casual. I saw clearly he had a lot of interests. Was I seeing the budding philanthropist he'd become in the future?

And he liked to joke with me, trying to soften the gritty tone of the film. In an innocent way, I played house with Paul. Our cell-like dressing rooms were right next to each other, somewhere upstairs in the huge warehouse that was now our studio. We each had only a cot and a small table. I set up a hot plate in my room and brought soups for myself for lunch. One day Paul told me of a favorite imported dehydrated soup that he loved. After that I made a point of getting that soup or something close to it, heating it up, and bringing him a mugful at lunchtime. I sat on his cot with him while we both smiled and ate. It was a silent bonding time. One day Paul invited me to join him and his wife, Oscar-winning actress Joanne Woodward, at a fund-raiser ball for the Actors Studio. I had met Joanne only once. She visited the set for a brief time, wearing a beautiful red coat. I believe it was the only time she came to the set to see Paul. I thought it was very sensitive of her. My boyfriend John was shooting in California, so Paul and Joanne suggested their friend Gore Vidal be my escort to the ball. The night of the ball we all met at the Newmans’ apartment (I had heard about their dining room, and yes indeed, it was completely empty save for a large pool table). Joanne wasn’t quite ready and invited me to come back to the bedroom to keep her company while she was finishing up. A couple of flourishes to her hair, a powder puff, and some jewelry. I doubted I would have been that open with a woman I didn’t really know, but John, who knew her, was right; he had described her as someone I would like, “a really straight dame.” Gore Vidal was charming and witty, and the evening seemed festive. It was a release for everyone.

Every morning while we were shooting, the hairstylist would come to my apartment and blow-dry my hair straight in front of the makeup mirror. Then she’d wrap my head carefully with fine tulle to protect it for the drive to the location or the studio. One day Paul asked if I’d like him to pick me up for work in the morning on his motor scooter. Of course, I said yes. The next morning we flew through Central Park. It was beautiful, no traffic, round and around through the trees. Somewhere in Central Park my head covering floated away, but I didn’t care. Bob Rossen greeted us when we arrived at the studio and gave us both holy hell before he sent us to makeup. Rossen was very caring of me, beyond my being the actress in his movie. When he found out I was not sleeping well, he hired a masseuse to come to my apartment a couple of times a week at the end of the day. It didn’t help my sleep much, but it sure felt good. When I’d first told John I was going to do the movie, he’d asked about Rossen’s interest in me. Was it personal or strictly professional? I told him I thought it was both. There had been some unspoken but palpable anger between Rossen and Paul on the set. I think Paul may have been aware that he was not Rossen’s first choice, and that couldn’t have made things easier. Rossen once told me that his dream casting would have been John Garfield, if he’d been alive, or Peter Falk, whom the studio vetoed because he wasn’t a big enough star. Peter was terrifically attractive in the days before he dressed himself down for Columbo.

One day I went to Rossen and told him that I didn’t think I should be wearing clothes in the scene where Fast Eddie and I first wake up in bed. I should at least appear as if I weren’t. The bedsheets would hide most of my body. The production code was still very strict at the time; even married people could not be seen sleeping in the same bed. But Paul and I would be in the same bed, and Paul, of course, wouldn’t be wearing much, so why should I? I asked Rossen to tell Paul what I was planning to do beforehand so it wouldn’t be a total surprise. Rossen said, “I don’t think Paul is going to like that; he may be uncomfortable.” But nothing more was said about it, and that’s what we did. Rossen shot two versions: one for the foreign market, with Paul and me undressed under the sheets, and one for the United States, with me wearing a robe and lying on top of the sheets and Paul wearing a T-shirt. Interestingly, the acting in the clothed scene was far better, so that’s the one that was used. A few days later John went back to California to finish All Fall Down. Paul had seen John coming to pick me up at the rehearsal hall after work when John visited. He used to say to me, “Why don’t you marry the guy?”

I didn’t know if Paul was serious or not, but that idea, even with John, was frightening to me. It took fifteen years to pass for me to see the genius of what was done, of editor Dede Allen’s brilliant work. How perfect the movie is. I saw how wrenchingly sensitive Paul’s Fast Eddie was, and how brave. He made me weep over my own (Sarah’s) death. It’s a pity it took me so long to see it. There were lots of subsequent screenings of The Hustler, and though I did not attend them, I heard about them. Everyone seemed to love the movie, even the critics. —Learning to Live Out Loud (2011) by Piper Laurie

By the time of The Hustler’s completion, Rossen summed up one capsule version of his intentions in this way: “The game represents a form of creative expression. My protagonist, Fast Eddie, wants to become a great pool player, but the film is really about the obstacles he encounters in attempting to fulfill himself as a human being. He attains self-awareness only after a terrible personal tragedy which he has caused—and then he wins his pool game. Eddie needs to win before everything else; that is his tragedy.” In later discussions, Rossen touched on more intertwined aspects of the themes. “Filming The Hustler, I was extremely conscious of what I was doing from beginning to end. In every region, on every level, from that of billiards to the fact that Eddie associates with a cripple. In fact, why is she lame? It is hard to say, and yet it could not be otherwise. He too is a cripple, but on the level of feeling, while she is one even physically.” He spoke of this again when he was asked about his tendency to speak of disability in his last films. He replied, “It is because if I look at the world in which we live, if I think about this world of today, I cannot keep from seeing in it a great number of cripples, and I want to speak of them with sympathy, to try to understand them.”

In April 1966 the influential French journal Cahiers du Cinema devoted a special issue to Rossen’s work, two months after his death. It was an important, if still limited, re-claiming of the value of his work—at least in Europe. In his homage to The Hustler, Jacques Bontemps poetically evoked this motif of being “crippled” and its relationship to a central theme of knowing yourself, of attempting to know and connect to others: This was a story of wounded ones, of isolated ones, of unknowns. Constrained to limp alone. At the threshold of the insurmountable strangeness of the other was revealed an irremediable strangeness to one-self. Bontemps wrote of one provocative sense of these resonances: “The film, its story full of digressions and lacunae, said that, essentially ‘hustled,’ each person was perhaps most deeply his own ‘hustler’ forever.” For Rossen, the materials of the story, as he adapted them, resonated on a personal level. With the ideological turmoil of the blacklist and testifying somewhat loosening its hold on his imagination, he sensed in this narrative a parable on the hustlers of Hollywood—at any time. Bontemps, again, was insightful on this implication, writing that in “a universe dulled with leveling... the one who wins is not the one who concerns himself with the beauty of the gesture, but he for whom everything poses itself in terms of efficacy of return. Compromise and resignation are required. There is a place only for Bert or for Minnesota Fats.”

The gesture of The Hustler, with its own kind of beauty, is jagged and unsettling, a paradox. As Claude Ollier had perceptively written when the film first came out, what gives The Hustler its special quality, its staying power, goes beyond its “ultra-classical skill.” It is that “one has the constant impression that something else is happening that is escaping, being only briefly suggested by acting and dialogues with two meanings.... A sense of indecision hovers permanently over this strange film, and the final explanations are not enough to dispel it.” Nevertheless, the preconceptions of the critics kept most from seeing The Hustler for what it really was. Most critics, while praising it, did not allow it to resonate on these deeper themes. Some even complained that the whole affair with Sarah—the crux of the film’s deepest feelings and insights—was too depressing and destructive. Brendan Gill in The New Yorker felt Rossen had become “over-ambitious.” He bemoaned “the marvelous picture it might have been if it hadn’t got so diffuse.” For Gill, Bert Gordon was another “tough gangster-gambler.” Pauline Kael dug a bit deeper into it: “George C. Scott in The Hustler suggests a personification of the power of money. The Last American Hero isn’t just about stock-car racing, any more than The Hustler was only about shooting pool.” She does not, however, go on to differentiate the vast differences in insight and artistry in dealing with what else the two films were about. The Hustler is the most achieved and fulfilled of Rossen’s films. It is the quintessential version of Rossen’s deepest, abiding interests and insights, his core sense of the shape of things, and his unflagging hopes. Rossen felt that we could all be driven through the turbulent, often inexplicable flux of our inner weaknesses and external pressures, to betray others—and ourselves.

Certainly part of the work’s artistic fulfillment was his writing the best dialogue of his career—credible and moving, yet thoughtful, meaningful, and even iconic. Rossen’s wonderful use of Cinemascope (in black and white) to create an oppressive, elongated world in which ceilings always seem terribly low; and people terribly separate from each other; in one shot Newman is even separated from his own image in a mirror by almost the whole width of a very wide screen. It is a world in which the pool table seems the one natural shape, while human beings seem untidy intruders, and that, of course, is the film’s chief concern: the human cost of being the greatest pool player in America. This sense of oppressive, enclosing settings—décor in the broadest sense—is one of the central constellations of visual motifs that span the structure of the film. These settings help to shape the restricting pressures of the world in which the characters live—their enclosed trap and arena. Only one major scene takes place within an outdoor setting. The sensitive, quietly magnificent cinematography of Eugen Shuftan captures and projects every nuance.

In Rossen’s parable of the artist in Hollywood, all are merely human, all are hustlers. They need—to win, to be right, to believe. The artist strives too much to hustle and win, to be a success; the Party member goes beyond reason to hold on to his beliefs. The more either (or both in one) hustles and strives, the more he betrays his gift, his élan, betraying his ideals and dreams of a better world. And the more he strives, the more he ends up placing himself in the hands of the moguls who not only want to control the product, but, like the gambler Bert Gordon, want to own and control the people who create it for them—or in the bloody hands of political tyrants, who, too, must control all in ways that have even more dire and dreadful results. But Bert is a more subtle Hollywood power broker, a Congressional Committee member, a Communist Party manipulator. He too is one of those who will use you and break your spirit if he has to. Bert’s drive for power rises from an ego that is paradoxically both strong and uncertain.

The woman in this strange triangle of struggle and power also is more fully, and ambiguously, developed than any of Rossen’s previous female characters. Patric Brion even saw “the center of interest displaced from Paul Newman to Piper Laurie and, indeed thereby, acquiring a very attaching [attachant, engaging] truth and tenderness.” He saw Sarah as a mid-point in an important new strain of interest, from Adelaide in Cordura to Lilith. Sarah is a potential artist, a writer, but far from the perfection of her counterpart, Peg, in Body and Soul. She understands and spreads the value and joy of love (a scene lovely in her awkwardly winning openness when she goes shopping and girlishly proclaims, “I’ve got a fella”). But, lame and alcoholic, she too is psychologically crippled. She is, as Bert Gordon recognizes, a born loser. Too familiar with defeat, Sarah is drawn to it, almost seems to need it. And so she cannot help herself; she lets Bert Gordon win, and lets herself betray Eddie and herself, as though she just couldn’t fight anymore, as though that were the only tragic way left for her to win. ”Well, what else have we got? We’re strangers. What happens when the liquor and the money run out, Eddie? You told Charlie to lay down and die. Will you say that to me too?” When he slaps her, she says coldly “You waiting for me to cry?” Wearing a jacket and tie, he had taken her to a fancy French restaurant. She won’t believe him, can’t. “Is that your idea of love?” “I got no idea of love,” he answers. “And neither have you. I mean, neither one of us would know what it is if it was coming down the street.” She says later, “They wear masks, Eddie. And underneath they’re perverted, twisted, crippled. Bert's not going to break your thumbs. He’ll break your heart.”

Sunday, August 14, 2022

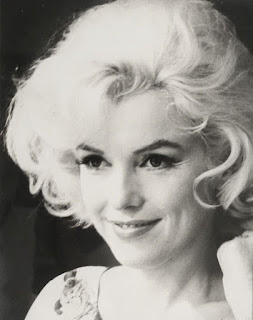

The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe: The Unheard Tapes (Analysis by Donald R. McGovern)

Cassette 93B: Eunice Murray, Marilyn Monroe's housekeeper and author of Marilyn: The Last Months (1975)

The taped testimony offered by Eunice Murray, at least the testimony included by Anthony Summers in his recent documentary Marilyn Monroe: The Unheard Tapes appeared to confirm that Robert Kennedy visited Marilyn; but did Marilyn’s housekeeper actually say on August the 4th? Well, no she did not. We know that Robert Kennedy visited Marilyn, accompanied by Pat and Peter Lawford, on the 27th of June in 1962. Eunice Murray recounted the attorney general’s brief visit on that Wednesday for biographer Donald Spoto: the Lawfords arrived at Fifth Helena that afternoon to collect Marilyn, and Robert Kennedy was with them: Marilyn wanted them to see her new home.

After a brief tour of Marilyn’s humble hacienda, the group proceeded to the Lawford’s beachside mansion for a dinner party. That June visit, residential tour and dinner party was the fourth and final meeting of Bobby and Marilyn. Certainly the president and the attorney general knew that anything they said about Marilyn’s death would have been promptly misconstrued, would only have served as a potent fertilizer fomenting more suspicion, speculation and rumor. Furthermore, the fact that Tony Summers included the statements of Harry Hall and James Doyle showed a lack of balance plus an eagerness to accept the most illogical and ahistorical kind of testimony. For instance, that somehow there were FBI agents on the scene of her home in the early morning hours of August the 5th, which no credible author has ever noted. FBI Counter-intelligence chief William Sullivan said his boss J. Edgar Hoover tried to inflame rumors about an affair between Bobby Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe. The problem was, neither the boss nor his minions could find any evidence of an affair. Why did Hoover want to do this? Because Bobby Kennedy was the only attorney general who actually acted like he was Hoover’s boss. For instance, Hoover wanted to do next to nothing on civil rights, but Bobby Kennedy ordered him to. But even at that, Hoover would not reveal undercover information that could have prevented bloody violence during the Freedom Rides. (See Irving Bernstein, Promises Kept, 1991)

When President Kennedy went up against steel executives in 1962, FBI agents served subpoenas to J. Edgar Hoover in the wee hours of the morning. Hoover got back at the Kennedys by doing things like spreading rumors about the president and Ellen Rometsch, a reputed East German spy working out of Washington. When ace researcher Peter Vea discovered the raw FBI reports on Rometsch, there was nothing in there about an affair between her and the president. The testimony of friends and confidants, those who actually knew Marilyn Monroe, would at least cast reasonable doubt, if not virtually disprove, all the malarkey posited by those who have used her for financial gain and yet never knew her nor even met her. But more importantly, why has Marilyn’s own testimony been omitted, why has her own voice been silenced by the conspiracists? Because every conspiracy theory and virtually every allegation of affairs with the middle Kennedy brothers and sundry mobsters began after Marilyn’s death; it began with rumors and innuendo; and the actual testimony offered by the woman involved, limited though it is, contradicted all the wild allegations.

On a Friday afternoon in Chicago, August the 3rd, Robert Kennedy boarded an American Airlines flight in Chicago connecting from Washington, DC. The attorney general joined his wife, Ethel, and his four eldest children, Kathleen, Joseph II, Robert Jr., and David. The American flight proceeded to San Francisco where the Bates family awaited their weekend guests. John Bates, Sr. then drove the group southeast from San Francisco to Gilroy, a pleasant two hours drive into the picturesque Santa Cruz Mountains. From Gilroy they drove an additional twenty minutes West to the Bates Ranch located just north of Mount Madonna. The Kennedy family spent the entire weekend with the Bates family on their bucolic ranch. The preceding account is an irrefutable fact. Also on the flight was the FBI’s liaison to the attorney general, Courtney A. Evans. An FBI file no. 77-51387-300, written by Evans, memorialized the Kennedy’s weekend excursion: The Attorney General and his family spent the weekend at the Bates ranch located about sixty miles south of San Francisco.

In the 1985 print version of Goddess, Summers mentioned the Kennedy family’s visit to the Gilroy ranch; but exactly how the families occupied themselves on Saturday, August the 4th, would not be revealed for eight years, appearing finally in Donald Spoto’s 1993 publication. According to John Bates, Sr., they returned to the ranch where the afternoon included a BBQ, swimming and a game of touch football. Due to the ranch’s hilly terrain, the participants had to locate a spot with a relatively level topography. That search consumed two hours of their trip. After the football contest, the group enjoyed more swimming; and then, the attorney general tossed his children into the swimming pool. Once the children had been put to bed, the adults enjoyed a peaceful dinner. The conversation during dinner focused predominantly on a speech the attorney general would deliver to the American Bar Association in San Francisco on Monday, August the 6th. According to John and Nancy Bates, dinner ended at approximately 10:30 PM, after which the fatigued adults retired.

John Bates, Sr. and Nancy along with John Bates, Jr. and Roland Snyder, the ranch foreman, testified on more than one occasion that Robert Kennedy never left the ranch during that fun-filled Saturday. More importantly, though, a group of ten photographs taken that day clearly depicted each activity as described by the Bates family and clearly confirmed that Robert Kennedy was at the ranch all day; and he was an active participant in all the day’s activities; therefore, how could anybody contend that Robert Kennedy was in Brentwood on August the 4th and visited Marilyn in the afternoon or night? It is mystifying indeed since any absence by Robert Kennedy would have been immediately noticed by any and all present, particularly Robert Kennedy’s children. Roland Snyder stated emphatically: "They were here all weekend, that’s certain. By God, he wasn’t anywhere near L.A." John Bates, Jr. recalled: "I was fourteen at the time and was about to go off to boarding school. I remember Bob Kennedy teasing me about it, saying, “Oh, John, you’ll hate it!” The senior Bates told Donald Spoto: "I remember Bobby sitting with the children as they ate and telling them stories. He truly loved his children." August the 5th was a significant requirement: the group attended an early morning Mass in Gilroy. On August the 6th, the local newspaper The Gilroy Dispatch printed a brief article entitled “Robert Kennedys Visits Local Ranch.” After commenting on the attorney general’s Monday speech, the article noted: "Robert Kennedy, his wife and four oldest children have been the guests of Mr. and Mrs. Jack Bates of Piedmont at their Gilroy ranch on Sanders Rd. They are expected to leave tonight when they fly on to the Seattle World’s Fair. Sunday morning the Kennedys attended 9 o’clock mass at St. Mary’s Church in Gilroy."

In 1973, to the Ladies Home Journal and The Chicago Tribune, Eunice Murray reported that Robert Kennedy did not appear at Fifth Helena on August the 4th, a position that she also maintained in her 1975 memoir. During an interview with Maurice Zolotow, published by the Chicago Tribune on September the 11th in 1973, Mrs. Murray asserted that the stories about Marilyn and Robert Kennedy were the most evil gossip of all before declaring: "It is not true that Marilyn had a secret love affair with Mr. Kennedy and I would tell you if it were so." She recalled the Wednesday visit in June of 1962 when the attorney general, accompanied by the Lawfords, came to see the house, finally adding that Marilyn certainly didn’t have a love affair with him. When asked directly by Zolotow if Bobby Kennedy was in the house that Saturday night, Eunice answered: No. After Zolotow posed the same question about Peter Lawford and Pat Newcomb, Eunice answered: No. Absolutely not. There was nobody in the house that night except Eunice Murray and Marilyn. The doors were locked. The windows locked. The French window in her room locked. And the gate was shut.

On March the 21st of 2022, Megyn Kelly interviewed Robert Kennedy, Jr. a mere six decades after the events of 1962; and to her everlasting credit, she broached the topic of Marilyn Monroe. Robert Jr. admitted: There’s not much I can tell you about Marilyn Monroe. But Megyn Kelly pressed the issue: The rumors are that she had an affair with your dad, that she had an affair with your uncle and even possibly that your dad was somehow there the night that she died out in California. Robert Jr. responded as follows: "Those are rumors that have been time and again proven completely untrue. There’s two days … my father’s schedule, every minute of his day is known. So people know where he was every moment of the day and it happens that the day that they say that my father, you know, that these people who are selling books and these things … that day that they say my father was with her he was with us at a camping trip up in Oregon and northern California and it would have been impossible for him to be there, though that was the day she died. These authors, who are just bogus authors, are making money by saying these things, all the days that they claim my father could have been with Marilyn Monroe are days when we know exactly where he was". Unfortunately, Megyn Kelly lapsed into the same fallacious argument employed by many persons who suffer from faulty reasoning based on weak analogies: since John Kennedy was an inveterate philanderer, then his brother must have been as well. But then, many of Robert Kennedy’s friends and associates have asserted over the years that he was disinclined to engage in extramarital activities. In 1973, Norman Mailer published his biographical novel of Marilyn Monroe. Concealed within Mailer’s lavender prose and his frequent flights of whirligig rhetoric, he offered the following proclamation: If the thousand days of Jack Kennedy might yet be equally famous for its nights, the same cannot be said of Bobby. He was devout, well married, and prudent. While John Kennedy would, in today’s enlightened society, undeniably be diagnosed a sex addict, his younger brother might be diagnosed a puritan.

Biographer Ronald Steel speculated that if Robert Kennedy had been born into a poor family without a power-hungry patriarch driving the boys into politics, he might have been a priest. Steel described Robert Kennedy’s religious ideology as a fierce brand of Irish Catholicism and that the attorney general was in his heart―and always was―a Catholic conservative deeply suspicious of the moral license of the radical left. Robert Kennedy did not embrace the drug culture and sexual permissiveness of the ’60s. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. offered the following: Robert Kennedy lived through a time of unusual turbulence in American history; and he responded to that turbulence more directly and sensitively than any other political leader of that era. He was equipped with the certitudes of family and faith―certitudes that sustained him till his death. According to Richard Goodwin, advisor to both John and Robert Kennedy, the attorney general, unlike the president, was temperamentally disinclined to philander or engage in extramarital activities, even with Marilyn Monroe.

The boast often proclaimed by Anthony Summers to extol his Marilyn pathography is that his research for Goddess included six-hundred and fifty interviews. However, in his Netflix doc, Summers included a mere twenty-seven of the recorded interviews. Of the interviews Summers tape recorded, six-hundred and twenty-three, the vast majority, remain unheard. An inquiring mind would immediately ask several questions. What, for instance, is the testimony on the vast majority of the still unheard tapes? According to Marilyn biographer Gary Vitacco-Robles, Summers omits interviews which contradict the interviews he chose to include. He uses interviews to support Kennedy was at Peter Lawford’s house in August 4; however, he interviewed all of Lawford’s guests that night and all reported Kennedy was not there. A case in point is the tape recording of Summers’ interview with Milt Ebbins. Several persons have heard it. Along with all of Summers’ tapes, the Ebbins tape is housed at the Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills, California. Why was that interview excluded from the Netflix flick? Also, it is painfully clear that at least one tape presented by Summers had been edited, and that tape was not the product of a Summers conducted interview: it was the product of an interview conducted by the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office. So, this imperative question follows: had any of the other tapes been edited especially for inclusion in the Netflix documentary?

Moreover, it should be obvious, and also troubling, that Summers withheld, excluded testimony from witnesses who actually knew Marilyn and, unlike Arthur James, could prove they knew her: Pat Newcomb would be a case in point. Others would be Ralph Roberts, Norman Rosten and Whitey Snyder. According to Summers’ source notes, he interviewed all of the preceding persons. Did he fail to tape record those interviews? But even more egregious is the exclusion of the first-hand, eye-witness testimony of the Bates family and Roland Snyder, all of whom spent that early August weekend with the Kennedys; and dare I even mention the exclusion of the Bates family photographs, ten of them, that memorialized and created a historical record of what happened at the Bates Ranch on Saturday, August the 4th, created a documentary record that Summers did not even deign to mention, much less pursue. Those photographs have been available since 1962; and Susan Bernard published them in 2011. If the purpose of his documentary was to present the facts, then why was essential and pertinent information withheld? The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe: The Unheard Tapes is not a documentary. It is a sensationalized melodrama featuring dramatized pantomime by unidentified actors, a cheesy and distracting tactic one reviewer noted; and viewers are treated to maudlin music and grimy film-noir-like cinematography.

The sensationalized melodrama is the result of Summers’ repeated suggestions that perhaps Marilyn’s death was the result of activities more diabolical than an overdose—Then at the seventy-eight minute mark, Summers announced: "So, I’m not at all of the mind of the loony people who write books saying she was murdered. I did not find out anything that convinced me that she had been deliberately killed." Legerdemain Summers certainly rivals Norman Mailer’s use of paralipsis on a narrative scale, in which the novelist indulged himself with insinuation and innuendo, theories of conspiracy to the point of tedium before finally admitting that Marilyn more than likely killed herself; and Mailer’s Kennedy narrative, like Summers’ Kennedy narrative, ends up being fundamentally incidental. Summers wrote in Goddess, Marilyn's mystery hinges on “scandal”―and scandal is a gaping excavation from which the sparkly twinkly jewels of insinuation and speculation can be mined almost without end, the actual truth notwithstanding. But then, ironically, as Marilyn said at the beginning of the documentary: "True things rarely get into circulation. It’s usually the false things." Source: marilynfromthe22ndrow.com

Monday, August 08, 2022

Raymond Chandler: The Detections of Totality

Widely considered an inveterate nihilist, the most misunderstood late 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, once observed: "In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering in innumerable solar systems, there once was a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the highest minute of 'world history' - yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star grew cold, and the clever animals had to die." Russian writers of the period like Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, Herzen and Chernyshevsky are almost unmatched in portraying nihilism in thought and action. Examples of extreme nihilism can be found in characters, largely villainous, who stress on how life, the universe, and everything are all meaningless to fight over, how existence is insignificant, and morality illusory. Homer's Iliad, is one example, others can be found in the works of H.P. Lovecraft, Ayn Rand, Joseph Conrad, George Orwell in "1984" and in "Keep The Aspidistra Flying".

However, it is the other end that should be of more interest - and value for us is the "anti-nihilism" whose proponents, occasionally being nihilists themselves, are maybe of a more realistic and constructive sort. They are, by no means, under any illusions of the beneficence of their world or society or fellow people, and know how terrible and unfair all these can be, but still, as a conscious choice, they choose to be caring, loving, or compassionate. For they do not seek to revel in despair or dissipate their intense cynicism - which remains internal, but arrogate to themselves the right, the power to create meaning, values and purpose in their life. Hollywood director Stanley Kubrick summed it up well: "The most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile, but that it is indifferent. However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light." Like their polar nihilist counterparts, the anti-nihilists also know compassion, love and empathy are only fictional, but the difference is that for them, these are fictions still worth believing in, and acting on.

Most conscientious private detectives (Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe, in line with the author's "Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean..." sentiment), police officers (say Martin Beck and his friends in Per Wahloo and Maj Sjowall's pioneering Nordic crime fiction series, Steve Carella, Mayer Mayer, and others of Ed McBain's 87th Precinct), and even superheroes, are the best example of these tropes in fiction. Take Batman: Bruce Wayne, having undergone a seemingly random and meaningless tragedy that left him an orphan, could have decided that life itself was meaningless and turned to depression. Instead, he chose to focus on what his parents meant to him and to his home city Gotham, re-inventing himself as a champion of order and justice, against the mayhem and chaos caused by the Joker, the Penguin, and the like.

Terry Pratchett's Discworld books feature quite a few proponents as principal protagonists, especially Death, represented as an anthropomorphic personification, and is wise too ("You need to believe in things that aren't true; how else can they become?"), and City Watch commander Sam Vimes. But the best example is Lord Vetinari, the city's competent and benevolent ruler, who repeatedly mocks the inherent evil/stupidity of people, but perseveres on for them regardless. He once also goes on to give a graphic example of the indifferent cruelty of nature he observed, and concludes it taught him that if there was a supreme creator, it was the duty of every sentient being to become a moral superior. Camus uses the mythological villainous Greek king, condemned to ceaselessly roll uphill a heavy boulder - which rolled back to the base as soon he reached the summit - to show why we must keep doing what we have to do without thinking it futile. "...The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy," he ponders. Source: theconversation.com

Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson’s essay on Raymond Chandler: The Detections of Reality is interesting yet also frustrating in its constant search of analogies fitting into a Marxist context. The essay is actually a monograph consisting of three chapters whose main thesis is that Chandler’s novels are all essentially the same story, and Marlowe travels from space to space, the spaces each defining different socio-economic realities. The ‘crimes’ are all incidental; the search/journey is the point. In the end, the search validates Heidegger’s distinction between the ‘world’ and the ‘earth’—our historical/cultural ethos and the material world in which it is set. Marlowe discovers that separation and thus offers an interesting example of modernism which reinforces the theories of such continental thinkers as Barthes, Benjamin, Jakobson, Althusser and Heidegger. When Chandler studied at Dulwich he came under the influence of A. H. Gilkes, who had a profound respect for the ‘common man’—a view that affected P. G. Wodehouse, C. S. Forester and other prominent writers. This, along with Chandler’s own painfully-won knowledge of British snobbery helped to shape his views of culture and society. Jameson argues that the real villains in Chandler’s crime novels are “societal” villains, e.g. police corruption; the Chandler villains are all “institutional”—big government, big unions, organized crime, big business, and so on and it is his ongoing argument that these structures are often in cahoots with one another and always at the expense of the lone, decent individual. Chandler makes this point at length in the peroration of “The Simple Art of Murder”. That isolated individual struggling to be heroic in the face of long odds and long guns is Chandler’s hero and he fits very nicely within the ethos of both modernism and film noir. It is one of the truly interesting aspects of twentieth-century literature that there is not a long distance between Eliot’s Waste Land and Chandler’s Los Angeles. Source: criticalinquiry.uchicago.edu

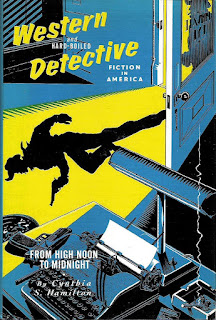

Professor of Cultural History and American Literature Cynthia S. Hamilton writes in Western and Hard-Boiled Detective Fiction in America: From High Noon to Midnight, "Chandler's misanthropy demands an absolute separation between Marlowe and the moral squalor of his society". In her view Marlowe is antisocial, an "alienated outsider who vindicates that stance by his demonstrable superiority in a society unworthy of his services." Chandler took on the daunting challenge of using the highly individualistic figure of the private eye to explain how and why American rugged individualism has failed. Chandler reserved his bitterness and contempt for society as a whole and those who occupied the upper echelons in society in particular, whom he considered “phoney.” Roy Meador observed the disillusioned affinity between Chandler's The Big Sleep and John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wraith, also placing them alongside Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust; all of which were published in 1939. However, of these novels, Meador argues that The Big Sleep is by far the most popular because as a character, “Marlowe encompasses the others and reaches out to new dimensions”.

One might then expect Chandler's class bias to have endeared him to a Marxist critic such as Ernest Mandel, who, however, feels that Marlowe, among other detectives, is a sentimentalist who wastes his energy on pursuing criminals who wield only "limited clout". It is doubtless Chandler's reluctance to make any global condemnation of the capitalist system that bothers Mandel. Chandler consistently and symbolically sought redress for social ills within the democratic system as he knew it in the United States, within the liberal tradition. In "The Simple Art of Murder," he insisted that no social or political hierarchy is truly divorced from the "rank and file" in a democracy, and thus cannot be completely blamed for its failures. Ross Macdonald's primary criticism of Chandler is that he is too moralistic; Like other critics, Macdonald misreads Chandler's "The Simple Art of Murder," overemphasizing Chandler's call for "a quality of redemption" as a "central weakness in his vision" in novels. Chandler isolates his hero, Philip Marlowe, by means of "an angry puritanical morality". Chandler's deepest concerns - his interest in the community as well as the individual, his hatred of the abuse and the abusers of power, his conviction that ethical conduct must be continually scrutinized - are inevitably what Hollywood was most concerned to change onscreen.

Where Carroll John Daly's, Dashiell Hammett's, and Mickey Spillane's heroes display the self-sufficient, self-aggrandizing traits of classic rugged American individualism, Chandler—through Marlowe—is sometimes prone to critizice the individualist myths. In a world in which the police are as guilty of egregious violence as criminals, Marlowe roundly condemns both; his toughness is measured not by resorting to such extreme measures, but by his refusal to respond violently to the threats of gangsters (Eddie Mars in The Big Sleep, Laird Brunette in Farewell, My Lovely) or the police (Christy French in The Little Sister, Detective Dayton in The Long Goodbye). "No matter how smart you think you are, you have to have a place to start from; a name, an address, a background, an atmosphere, a point of reference of some sort," says Marlowe in The Long Goodbye. In transforming the figure of the hard-boiled detective, Chandler created a new paradigm, not only for a new detective, but for a new individual as well.

Toward the end of his life, Chandler came to feel that L.A. had become a grotesque and impossible place to live. It was a “jittering city,” sometimes dull, sometimes brilliant, but always depressing to him. In his later years, Chandler commented that he felt L.A. had completely changed in the years since he’d arrived. Even the weather was different. “Los Angeles was hot and dry when I first went there,” he said, “with tropical rains in the winter and sunshine at least nine-tenths of the year. Now it is humid, hot, sticky, and when the smog comes down into the bowl between the mountains which is Los Angeles, it is damned near intolerable.” The function of the work of art is to open a space in which we are called upon to live within an existential tension. Chandler’s novels insist on this “unresolvable tension,” his work at best exemplifies noir as existentialism, engendering for readers what amounts to a spiritual ethic—a practice of balancing in the void.

Raymond Chandler was otherwise described, in the course of his life, as cynical and gullible; reclusive and generous; depressive and romantic; proud and paranoid. The influence of Chandler is far beyond a detective novelist (he admired Dickens, Flaubert, and Fitzgerald). Chandler was admired by W.H. Auden, Camus, and Graham Greene. Black Mask was a pulp magazine which had been set up by two New York editors in 1920 to support the lossmaking but prestigious literary magazine Smart Set. The connection with Smart Set – whose most famous contributor was F. Scott Fitzgerald – was an ironic one for Chandler. Despite being his predecessor, Chandler did not consider Hammett to be an especially good writer: ‘What he did he did superbly,’ decided Chandler, ‘but there was a lot he could not do. For all I know, Hemingway might have learned something from Hammett.’ "Marlowe was an idealist," Chandler admitted, ‘he hates to admit it, even to himself.’ Chandler believed that the entire intellectual establishment was in a state of terminal self-delusion, cut off from the public it despised. Such people thought they could write, he said, ‘because they have read all the books, but they are in fact hacks’.

Suspicious as he was of most institutions, Chandler was politically non-partisan. The trouble was, he believed, that post-war Western culture was being controlled by the first generation of highbrows not to have a grounding in the classics. Without God and without heroes, it was a generation that admired the art of writing itself rather than writing about things that meant anything. Nervous fashion had replaced wisdom. ‘The critics of today’, he told Charles Morton, ‘are tired Bostonians like Van Wyck Brooks or smart-alecks like Fadiman or honest men, confused by the futility of their job, like Edmund Wilson.’ They were all hooked on syntax and pessimism, ‘the opium of the middle classes’. To a correspondent who suggested that Marlowe was immature, Chandler replied sharply that if being in revolt against a corrupt society was immature, then Marlowe was extremely immature. -"Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe: The Hard-Boiled Detective Transformed" by John Paul Athanasourelis (2017)

Thursday, August 04, 2022

Marilyn Monroe's 60th Anniversary of her death

In interviews with over 700 people, Anthony Summers, author of Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe (2017) encountered nothing to suggest that Daryl Zanuck or any Hollywood producer assaulted or raped Marilyn Monroe. Summers says he is fearful about Andrew Dominik's new film based on Oates' novel, Blonde, starring Ana de Armas. Summers said: "When Oates’ novel Blonde came out, her defence was that, in a work of fiction, she ‘had no particular obligation’ to the facts. In my view, that is not so. The people she named in her novel were real people with real reputations – and historical legacies – and such fictional fabrication is unjustifiably cruel. The fact that the individuals concerned are dead is no defence." ‘The scale of the Monroe myth is impossible to measure,’ Professor Sarah Churchwell wrote in her book "The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe" (2005): "More books have been written about the star than about any other entertainer. More than 20 films already offer a fictional version of her life story." Will the coming Netflix film be an indulgent wallow in her sex life and in conspiratorial fantasising about her death, or deliver something worthwhile? Source: theguardian.com

Donald McGovern: Netflix, the gigantic streaming service did not invent scandalous or salacious entertainment, but they have the authorship of a content company that churns out such provocative reflections on reality, week by week. Its latest slop, served for an audience of armchair detectives, is a special kind of gross. The problem is you have to be familiar with the subject matter. Most of the public which watches this will not be. When I first learned that Netflix would be airing a doc that intended to reveal some previously unheard tapes obtained by Anthony Summers, I assumed the tapes would only be the interviews obtained by the author during his research prior to writing Goddess. These mysterious secret tapes were purportedly made by private detectives Fred Otash, Bernard Spindel, and Barney Ruditsky, all three of questionable character and honesty. Of course, Summers offered some commentary about his investigation into Marilyn’s life, but primarily her death and her sex life. Some of the interviewees knew Marilyn, or alleged they knew her anyway; but most of the persons that Summers interviewed, or at least the tapes of interviews that he included in the movie, operated on the periphery of Marilyn’s life.

Several persons who were actually an integral part of her life, Pat Newcomb and Susan Strasberg for instance, persons that Summers interviewed just to mention two, did not receive any airtime, did not even receive a mention. Marilyn’s three husbands, Jimmie Dougherty, Joe DiMaggio, and Arthur Miller did not appear. Marilyn comments prophetically: “Because the true things rarely get into circulation. It’s usually the false things.” But Anthony Summers certainly could not be interested in false things, could he? Marilyn signed her initial Fox contract on the 26th of August in 1946 at the tender age of twenty years. Besides, Al Rosen never represented Marilyn, a fact that did not, of course, preclude a possible acquaintanceship. Still, Summers did not tell his audience that Rosen was not Marilyn’s agent. Rosen told Summers that Marilyn and the powerful movie mogul, Joseph Schneck, were lovers. After all, Rosen concluded, “Schneck was a human being;” and Schneck was not alone. He was just one of Marilyn’s many potential human beings. Of course, Summers did not report that both Marilyn and Joe Schneck denied that they had been lovers. Each maintained steadfastly that their relationship was strictly platonic.

Marilyn Monroe denounced the rumors circulating through Hollywood that she was Mr. Schenck’s paramour. She called these rumors "scurrilous lies". Also, according to Marilyn, the aging producer never solicited her for sex. According to Albert Broccoli, who later produced several 007 movies, Schneck had kind feelings for Marilyn. Broccoli asserted that Marilyn’s wonderful smile invigorated Schneck: his face brightened when he saw her. All Joe Schneck wanted from Marilyn, according to Broccoli, was her friendship. But according to Rosen, Marilyn’s name was in the little black books of Hollywood moguls. The reason Summers and Netflix positioned Rosen’s interview at the start of their flick is painfully clear: it’s all about the voyeurism, it’s all about the sex. Still, just how well Al Rosen actually knew Marilyn and when he actually knew her is open to debate. And not one of the many Marilyn biographies that I consulted even mentioned Al Rosen. Hmm.

Marilyn’s psychological difficulties have been discussed and written about frequently; her personality and her behavior have been analyzed by psychologist and psychiatrist alike. Leading to diagnoses that Marilyn possibly struggled with a bipolar disorder along with a borderline personality. Her mood swings and her feelings could be extreme. Her thoughts could be intensely focused on her profound unhappiness. Tired of the incessant gossip, Marilyn asked both Rupert Allan and Ralph Roberts if they had heard the rumors regarding a romance between her and Robert Kennedy. When each man responded affirmatively, she responded emphatically that the rumors were false. And she confided in each man that Robert Kennedy, although she appreciated him, was not her physical type. Even Peter Lawford testified to the LAPD that what had been written by various authors about Marilyn and the middle Kennedy brothers was pure fantasy. And Lawford reported to Randy Taraborrelli: “All of this business about Marilyn and JFK and Bobby is pure crap. I think maybe—and I’m saying maybe—she had one or two dates with JFK. Not a single date with Bobby, though…” Also I have several serious issues with Arthur James’ testimony. But for the sake of brevity, I’ll discuss only one at this time: the assertion that Marilyn spent a weekend with her alleged good friend and confidant in Laguna Beach. James says that, “We met in Laguna a month before she died. She came down for the weekend and she told us…what had really taken place with the Kennedys.” There are only two weekends during which this purported visit to Laguna Beach could have occurred within a month of her death: the last Saturday in June and the first Sunday in July (June 30th and July 1st), or the first weekend in July (July the 7th and 8th)

I can only surmise that Marilyn did not inform Arthur James of any other life altering events that she had recently endured, at least not on the tape Netflix and Summers shared, just her alleged shattering break-up with the middle Kennedy boys. “As a person, my work is important to me,” she commented in early 1962. “My work is the only ground I’ve ever had to stand on.” Considering that her profession was in serious peril at that time, surely she would have mentioned that fact to her dear friend, Arthur James; and too, clearly there are calendar date conflicts. She could not have been in Laguna Beach if she was with George Barris at Santa Monica Beach or with Richard Meryman at Fifth Helena Drive giving an interview. Arthur James also testified that Marilyn “was terribly hurt when she was told directly never to call or contact” the Kennedys again. An order that supposedly came from both the President and the AG: “That’s the end of it.”

Curious. If Robert Kennedy abruptly dispatched Marilyn and ordered her not to contact him ever again, why did he and his wife invite Marilyn to attend a party at their Virginia mansion shortly afterwards? Under the circumstances described by Arthur James, for Robert Kennedy to have extended that invitation was certainly nonsensical. Researcher Donna Morel asked Arthur James if he had “any letters, photos or any type of evidence to substantiate his relationship with Monroe.” James admitted, just like Jeanne Carmen, Robert Slatzer, and Ted Jordan, that he likewise had no evidence, no proof that he even knew the world’s most famous movie star, much less that he was one of her confidants. But of even more importance is this: James denied asserting that Marilyn visited him at Laguna Beach in 1962, a month before she died. He reported to Donna that Marilyn’s weekend visit occurred “at least a year earlier than that. Then he seemed to indicate this happened in the early 1950s and she would stay at an apartment building he owned.” So, James denied saying what he had clearly said on tape; at least the tape that Summers decided to use.

A considerable amount of testimony pertaining to Robert Kennedy’s Puritanical attitude and behavior has been offered over the years. Testimony from acquaintances, friends, and even FBI agents dispatched by J. Edgar Hoover with the expressed mission of mining muck on one of Hoover’s archenemies. In his posthumously published memoir, William Sullivan, who was Deputy Director of the FBI under Hoover, asserted that the boss desperately wanted and attempted to catch Robert Kennedy in compromising situations. But the FBI director never did because Robert Kennedy “was almost a Puritan.” Agents of the FBI often observed him at parties during which the attorney general “would order one glass of scotch and still be sipping from the same glass two hours later,” Sullivan asserted. The stories involving a love affair between Bobby Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe were just that, stories started by Frank Capell, “a right-wing zealot who had a history of spinning wild yarns.” According to many persons who knew Robert Kennedy, he was a devout Catholic. And regarding whether or not Marilyn was under the influence of a “Bobby thing” or a “Jack thing,”

Jeanne Martin recalled that her impression was both. Miriam-Webster Dictionary defines impression as follows: “An often indistinct or imprecise notion or remembrance.” Gloria Romanoff, wife of restaurateur Michael Romanoff, briefly mentioned the Lawfords’ 1962 dinner party, which Marilyn and Robert Kennedy attended on the 1st of February, along with many other guests, including Robert Kennedy’s wife, Ethel, Pat Newcomb, Edwin Guthman, and John Seigenthaler. Tony Curtis and his wife, Janet Leigh, also attended, along with members of the media. As Gloria noted, during the dinner party, Robert Kennedy telephoned his father, who had recently suffered a serious stroke; and Marilyn spoke to the aging patriarch. During the course of that same evening, Gloria reported, Marilyn actually danced with the attorney general. John Seigenthaler, Robert Kennedy’s administrative assistant and his friend for most of his political life, noted in a newspaper article: “Yes, Robert Kennedy danced with Marilyn Monroe. So what? I danced with Janet Leigh. Ethel Kennedy danced with Tony Curtis and Bobby danced with Ethel. It was dinner, dancing, conversation—and that was it;” and according to Seigenthaler, Robert Kennedy’s social encounters with Marilyn were just that and nothing more. Besides, Marilyn’s friendly conversation with the ailing Joe Kennedy, Sr., who could barely speak, and her dance with Bobby, proved nothing, except this: any activity, regardless of its innocence, can be transformed into innuendo and used to suggest an ill intent; especially when one is looking for it."

Besides, Summers was primarily interested in Marilyn’s decline, a topic about which he often asked his interviewees; and he asked if Margaret Feury saw Marilyn “in the time of her deterioration?” Apparently, Feury did not respond anything. In May of this year, I contacted Joan Greenson via email. I hoped she would agree to open a dialogue with me, during which we could discuss Marilyn along with the Greenson family’s association with Anthony Summers. The Greenson family, I had been warned by Donna Morel, felt that they had been misled by Summers about the kind of book he was writing. On the same day Fox filed their lawsuit for breach of contract, Dr. Greenson sent Marilyn for an examination by Dr. Michael Gurdin, the eminent Beverly Hills surgeon. Greenson was alarmed when he saw that Marilyn’s eyes were black and blue and swollen. According to Dr. Greenson, Marilyn provoked her injuries when she slipped and fell while taking a shower. Even though Marilyn’s nose was not broken, she retreated to her Fifth Helena Drive hacienda, where she sheltered herself for sixteen days. She didn't want be seen in public with a bruised, discolored face.

The Netflix Blonde movie trailer intimates that de Armas’ character has Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). As a mental health condition that typically sees one person with a “host” personality and one or more “alters,” this implies that de Armas will not be playing Monroe in the traditional sense but will likely be playing Monroe as an alter for host, Norma Jeane. The trailer suggests that in this instance of DID the host personality has little or no control over the alters and vice versa. As detailed by the American Psychiatric Association, each personality state “takes control of the person’s behavior” and has a unique and distinct way of processing and relating to the world, frequently leaving the other states with long lapses in memory. This appears to be the case in the Blonde movie, with de Ana de Armas beginning the trailer as the host Norma Jeane at her dressing room, begging for her alter, Marilyn Monroe, to take control—thus relieving what appears to be an extremely shy Norma Jeane of a public appearance. While the implications of this speculative reimagining are substantial in respect to how the public perceives Monroe, the idea that Monroe was a product of Norma Jeane’s DID is surprisingly plausible.

As is commonly the case with those who develop DID, Norma Jeane is believed to have endured multiple forms of trauma at a young age. Furthermore, looking to Norma Jeane’s tragic death, especially untreated in the 1960s, people living with DID are prone to depression, drug addictions, and suicide. If the Blonde movie portrays de Armas’ character as one with DID, viewers will likely see de Armas playing Norma Jeane and Monroe as separate, distinct characters, but, interestingly, the trailer may suggest another alter as well. In the trailer’s final moment, the film’s title, Blonde, appears in three different fonts—an elegant, polished script for the “B,” followed by a less-refined, bolder “lond,” and finally a chalk-looking, printed, and perhaps child-like “e.” Considering this, it could be that the Blonde movie will see Norma Jeane as the host (in this case the most substantial part of the title), with Monroe being the elegant alter (and also the alter that the world sees first, i.e. the first letter of the title), and a second alter—possibly a child—represented by the title’s “e.” Accordingly, viewers should prepare to see Monroe in a whole new way and de Armas in the role(s) of a lifetime. Source: screenrant.com

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)

.jpg)

.jpg)