Widely considered an inveterate nihilist, the most misunderstood late 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, once observed: "In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering in innumerable solar systems, there once was a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the highest minute of 'world history' - yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star grew cold, and the clever animals had to die." Russian writers of the period like Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, Herzen and Chernyshevsky are almost unmatched in portraying nihilism in thought and action. Examples of extreme nihilism can be found in characters, largely villainous, who stress on how life, the universe, and everything are all meaningless to fight over, how existence is insignificant, and morality illusory. Homer's Iliad, is one example, others can be found in the works of H.P. Lovecraft, Ayn Rand, Joseph Conrad, George Orwell in "1984" and in "Keep The Aspidistra Flying".

However, it is the other end that should be of more interest - and value for us is the "anti-nihilism" whose proponents, occasionally being nihilists themselves, are maybe of a more realistic and constructive sort. They are, by no means, under any illusions of the beneficence of their world or society or fellow people, and know how terrible and unfair all these can be, but still, as a conscious choice, they choose to be caring, loving, or compassionate. For they do not seek to revel in despair or dissipate their intense cynicism - which remains internal, but arrogate to themselves the right, the power to create meaning, values and purpose in their life. Hollywood director Stanley Kubrick summed it up well: "The most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile, but that it is indifferent. However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light." Like their polar nihilist counterparts, the anti-nihilists also know compassion, love and empathy are only fictional, but the difference is that for them, these are fictions still worth believing in, and acting on.

Most conscientious private detectives (Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe, in line with the author's "Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean..." sentiment), police officers (say Martin Beck and his friends in Per Wahloo and Maj Sjowall's pioneering Nordic crime fiction series, Steve Carella, Mayer Mayer, and others of Ed McBain's 87th Precinct), and even superheroes, are the best example of these tropes in fiction. Take Batman: Bruce Wayne, having undergone a seemingly random and meaningless tragedy that left him an orphan, could have decided that life itself was meaningless and turned to depression. Instead, he chose to focus on what his parents meant to him and to his home city Gotham, re-inventing himself as a champion of order and justice, against the mayhem and chaos caused by the Joker, the Penguin, and the like.

Terry Pratchett's Discworld books feature quite a few proponents as principal protagonists, especially Death, represented as an anthropomorphic personification, and is wise too ("You need to believe in things that aren't true; how else can they become?"), and City Watch commander Sam Vimes. But the best example is Lord Vetinari, the city's competent and benevolent ruler, who repeatedly mocks the inherent evil/stupidity of people, but perseveres on for them regardless. He once also goes on to give a graphic example of the indifferent cruelty of nature he observed, and concludes it taught him that if there was a supreme creator, it was the duty of every sentient being to become a moral superior. Camus uses the mythological villainous Greek king, condemned to ceaselessly roll uphill a heavy boulder - which rolled back to the base as soon he reached the summit - to show why we must keep doing what we have to do without thinking it futile. "...The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy," he ponders. Source: theconversation.com

Marxist theorist Fredric Jameson’s essay on Raymond Chandler: The Detections of Reality is interesting yet also frustrating in its constant search of analogies fitting into a Marxist context. The essay is actually a monograph consisting of three chapters whose main thesis is that Chandler’s novels are all essentially the same story, and Marlowe travels from space to space, the spaces each defining different socio-economic realities. The ‘crimes’ are all incidental; the search/journey is the point. In the end, the search validates Heidegger’s distinction between the ‘world’ and the ‘earth’—our historical/cultural ethos and the material world in which it is set. Marlowe discovers that separation and thus offers an interesting example of modernism which reinforces the theories of such continental thinkers as Barthes, Benjamin, Jakobson, Althusser and Heidegger. When Chandler studied at Dulwich he came under the influence of A. H. Gilkes, who had a profound respect for the ‘common man’—a view that affected P. G. Wodehouse, C. S. Forester and other prominent writers. This, along with Chandler’s own painfully-won knowledge of British snobbery helped to shape his views of culture and society. Jameson argues that the real villains in Chandler’s crime novels are “societal” villains, e.g. police corruption; the Chandler villains are all “institutional”—big government, big unions, organized crime, big business, and so on and it is his ongoing argument that these structures are often in cahoots with one another and always at the expense of the lone, decent individual. Chandler makes this point at length in the peroration of “The Simple Art of Murder”. That isolated individual struggling to be heroic in the face of long odds and long guns is Chandler’s hero and he fits very nicely within the ethos of both modernism and film noir. It is one of the truly interesting aspects of twentieth-century literature that there is not a long distance between Eliot’s Waste Land and Chandler’s Los Angeles. Source: criticalinquiry.uchicago.edu

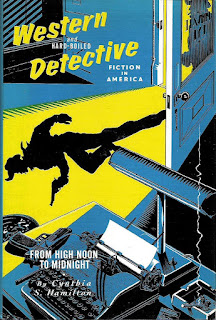

Professor of Cultural History and American Literature Cynthia S. Hamilton writes in Western and Hard-Boiled Detective Fiction in America: From High Noon to Midnight, "Chandler's misanthropy demands an absolute separation between Marlowe and the moral squalor of his society". In her view Marlowe is antisocial, an "alienated outsider who vindicates that stance by his demonstrable superiority in a society unworthy of his services." Chandler took on the daunting challenge of using the highly individualistic figure of the private eye to explain how and why American rugged individualism has failed. Chandler reserved his bitterness and contempt for society as a whole and those who occupied the upper echelons in society in particular, whom he considered “phoney.” Roy Meador observed the disillusioned affinity between Chandler's The Big Sleep and John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wraith, also placing them alongside Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust; all of which were published in 1939. However, of these novels, Meador argues that The Big Sleep is by far the most popular because as a character, “Marlowe encompasses the others and reaches out to new dimensions”.

One might then expect Chandler's class bias to have endeared him to a Marxist critic such as Ernest Mandel, who, however, feels that Marlowe, among other detectives, is a sentimentalist who wastes his energy on pursuing criminals who wield only "limited clout". It is doubtless Chandler's reluctance to make any global condemnation of the capitalist system that bothers Mandel. Chandler consistently and symbolically sought redress for social ills within the democratic system as he knew it in the United States, within the liberal tradition. In "The Simple Art of Murder," he insisted that no social or political hierarchy is truly divorced from the "rank and file" in a democracy, and thus cannot be completely blamed for its failures. Ross Macdonald's primary criticism of Chandler is that he is too moralistic; Like other critics, Macdonald misreads Chandler's "The Simple Art of Murder," overemphasizing Chandler's call for "a quality of redemption" as a "central weakness in his vision" in novels. Chandler isolates his hero, Philip Marlowe, by means of "an angry puritanical morality". Chandler's deepest concerns - his interest in the community as well as the individual, his hatred of the abuse and the abusers of power, his conviction that ethical conduct must be continually scrutinized - are inevitably what Hollywood was most concerned to change onscreen.

Where Carroll John Daly's, Dashiell Hammett's, and Mickey Spillane's heroes display the self-sufficient, self-aggrandizing traits of classic rugged American individualism, Chandler—through Marlowe—is sometimes prone to critizice the individualist myths. In a world in which the police are as guilty of egregious violence as criminals, Marlowe roundly condemns both; his toughness is measured not by resorting to such extreme measures, but by his refusal to respond violently to the threats of gangsters (Eddie Mars in The Big Sleep, Laird Brunette in Farewell, My Lovely) or the police (Christy French in The Little Sister, Detective Dayton in The Long Goodbye). "No matter how smart you think you are, you have to have a place to start from; a name, an address, a background, an atmosphere, a point of reference of some sort," says Marlowe in The Long Goodbye. In transforming the figure of the hard-boiled detective, Chandler created a new paradigm, not only for a new detective, but for a new individual as well.

Toward the end of his life, Chandler came to feel that L.A. had become a grotesque and impossible place to live. It was a “jittering city,” sometimes dull, sometimes brilliant, but always depressing to him. In his later years, Chandler commented that he felt L.A. had completely changed in the years since he’d arrived. Even the weather was different. “Los Angeles was hot and dry when I first went there,” he said, “with tropical rains in the winter and sunshine at least nine-tenths of the year. Now it is humid, hot, sticky, and when the smog comes down into the bowl between the mountains which is Los Angeles, it is damned near intolerable.” The function of the work of art is to open a space in which we are called upon to live within an existential tension. Chandler’s novels insist on this “unresolvable tension,” his work at best exemplifies noir as existentialism, engendering for readers what amounts to a spiritual ethic—a practice of balancing in the void.

Raymond Chandler was otherwise described, in the course of his life, as cynical and gullible; reclusive and generous; depressive and romantic; proud and paranoid. The influence of Chandler is far beyond a detective novelist (he admired Dickens, Flaubert, and Fitzgerald). Chandler was admired by W.H. Auden, Camus, and Graham Greene. Black Mask was a pulp magazine which had been set up by two New York editors in 1920 to support the lossmaking but prestigious literary magazine Smart Set. The connection with Smart Set – whose most famous contributor was F. Scott Fitzgerald – was an ironic one for Chandler. Despite being his predecessor, Chandler did not consider Hammett to be an especially good writer: ‘What he did he did superbly,’ decided Chandler, ‘but there was a lot he could not do. For all I know, Hemingway might have learned something from Hammett.’ "Marlowe was an idealist," Chandler admitted, ‘he hates to admit it, even to himself.’ Chandler believed that the entire intellectual establishment was in a state of terminal self-delusion, cut off from the public it despised. Such people thought they could write, he said, ‘because they have read all the books, but they are in fact hacks’.

Suspicious as he was of most institutions, Chandler was politically non-partisan. The trouble was, he believed, that post-war Western culture was being controlled by the first generation of highbrows not to have a grounding in the classics. Without God and without heroes, it was a generation that admired the art of writing itself rather than writing about things that meant anything. Nervous fashion had replaced wisdom. ‘The critics of today’, he told Charles Morton, ‘are tired Bostonians like Van Wyck Brooks or smart-alecks like Fadiman or honest men, confused by the futility of their job, like Edmund Wilson.’ They were all hooked on syntax and pessimism, ‘the opium of the middle classes’. To a correspondent who suggested that Marlowe was immature, Chandler replied sharply that if being in revolt against a corrupt society was immature, then Marlowe was extremely immature. -"Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe: The Hard-Boiled Detective Transformed" by John Paul Athanasourelis (2017)

.jpg)

No comments :

Post a Comment