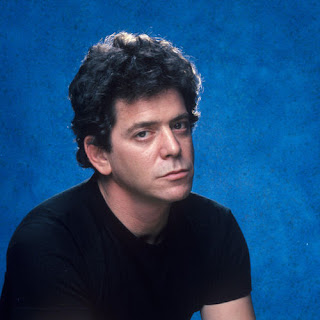

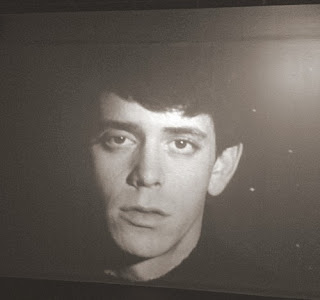

In the new Apple documentary "The Velvet Underground" (2021), Lou Reed says he made $2.35 royalties for his pre-Velvet song "Leave Her For Me", more than he made with the Velvets. But The Velvet Underground is, along with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, one of the three seminal groups in the history of rock ‘n’ roll. If you want to see the Velvets in their prime performing “What Goes On” or “White Light/White Heat” in a steamy rock club, or get a taste of what it was like to see the Exploding Plastic Inevitable at the Dom in New York City in 1966, you’re out of luck, because those clips basically don’t exist. It’s quite an irony considering that Warhol, the band’s mentor, was notorious for filming everything around him. The Velvet Underground, whose music was a mesmerizing midnight trance-out, had no radio niche, no publicity, no “media,” no backstage verité Pennebaker or Maysles. Todd Haynes appears to have vacuumed up every last photograph and raw scrap of home-movie and archival footage of the band that exists and stitched it all into a coruscating document that feels like a time-machine kaleidoscope that immerses you in the band but still leaves them slightly out of reach. The film interviews Reed’s sister, Merrill Reed Weiner, who sets us straight on the legendary tale of how the teenage Lou’s suburban Long Island parents okayed his getting electroshock therapy because they wanted to shock the homosexuality out of him. (She says that’s untrue.)

Lou the subversive guitar bad boy and Cale the debonair experimentalist came together like an acid and a base. Cale is the one whose story the documentary feels organized around. And that’s not just because Cale (now 79) is interviewed at length while Lou Reed, who died in 2013, couldn’t be. No, it’s as if Haynes wanted the Velvets to be an art band even more than he wanted them to be a rock ‘n’ roll band. The Velvets’ second album, “White Light/White Heat”, is written off in the movie as an angry amphetamine binge of a record. But out of that came drama: Lou Reed fired John Cale, just as he had already fired Andy Warhol. That sounds like reckless Lou, and that’s certainly the way the documentary presents it. But maybe Reed knew just what he was doing. He replaced Cale with Doug Yule, and together they made what I think is the group’s greatest album, “The Velvet Underground” (1969). It’s a masterpiece of religious street passion, yet the movie kind of brushes by it. Through it all, the Velvets, and perhaps only the Velvets, have remained perpetually hip. Source: variety.com

Lou Reed enjoyed a solo career renaissance primarily by passing himself off as the most burnt-out reprobate around (and it wasn't all show by a long shot). People kept expecting him to die, so he perversely came back, not to haunt them, but to clean up. The central heroic myth of the sixties was the burnout. Lou Reed was necessary because he had the good sense to realize that the whole concept of sleaze, of decadence, degeneracy, was a joke and he turned himself into a clown. In fact, a large part of Lou's mythic appeal has always been his total infantilism. Like Jim Morrison, Lou Reed realized the implicity absurdity of the rock 'n' roll bète-noire badass pose and parodied it, deglamorized it. Lou Reed, like all the heroes, is there for the beating up. They wouldn't be heroes if they were infallible, they wouldn't be heroes if they weren't miserable wretched dogs, the pariahs of the earth. –"Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung" (2013) by Lester Bangs

“All the books about me are bullshit,” Lou Reed once said, when asked about Victor Bockris' biography, although he reckoned there were lots of truth in Bockris' book. In a breezy tone, Reed’s first wife Bettye Kronstad wrote of the five-year period, 1968-1973, between the end of the Velvet Underground and Reed’s third solo album Berlin. Kronstad makes an effort in Perfect Day to contextualize what’s happening with their personal life with the goings-on of Reed’s career. But at its most interesting and tragic, this book serves to inject the well-worn myths of Lou Reed the legend with humanity, and offers an insider’s perspective to Reed’s losses of personal control, his fears and anxieties, particularly during the Transformer era. With a legacy of four commercial failures to his name, Reed didn’t exactly emerge as a hot property. Wearied from his Velvets experience and unsure about his next move, Reed ended up moving back to his parents’ house on Long Island and started a relationship with theatre student Bettye Kronstad. Bettye found him a kind, gentle, sensitive guy who nicknamed her 'Princess' and who telephoned her in the wee hours talking about his dreams of becoming a writer. In fact, they became serious and Bettye spent the first year she dated him living at his parents’ Long Island home.

Bettye Kronstad: "At seventeen, Lou’s parents had sent him to see a psychiatrist who prescribed EST for his depression and mood swings. During the summer of 1959, he was treated at Creedmoor State Psychiatric Hospital in Queens, New York, where the EST treatments were administered without an anesthetic. At that time, the procedure involved putting him on a wooden gurney with a rubber block between his teeth. This was an experience that scarred Lou for life. It is commonly thought that EST was prescribed to Lou in order to cure him of his ‘bisexual tendencies,’ but he never told me this or even alluded to it. I think he told journalists this to be more sympathetic to the gay community, and in part to broaden his appeal to that audience. From the beginning of our relationship I told Lou in no uncertain terms that if I saw a needle anywhere near him, I would—without fail—leave him. Hard drugs were his Achilles’ heel, and I knew they would destroy him if he started taking them again."

Shelley Albin: "Lou Reed is a very fifties type guy. He's ultimately straight. He wants his wife, Sylvia, who is a very fifties type girl, to take care of him." As much as Reed's sexuality was pondered, he had a long time girlfriend in Shelley Albin, and married three times. Reed even admitted his heterosexuality when initiated his relationship with Sylvia Morales. Reed's Ecstasy album addressed the failed marriage to Sylvia Morales (in the songs Baton Rouge and Tatters - she wanted kids, Reed obviously did not) and then he came with Set The Twilight Reeling, which dealt with his need to become "the newfound man, and set the twilight reeling" with Laurie Anderson.

Lou Reed was a self-sabotaging, widely disliked man who gave voice to the unwanted and despised. Like Danny Fields said once: "poor Lou - his act worked too well." Humanity brought out the worst in him, and he returned the favor. Anthony DeCurtis: "There was an incredible level of fear of abandonment and terror and that's what motivated his violence—coming out of a kind of desperation, it was less about hostility than about a kind of self-hatred and fear." As Lester Bangs wrote shortly after his first encounter with Reed: "I never met a hero I didn´t like. But then, I never met a hero. But then, maybe I wasn´t looking for one." "I just hope it doesn’t start getting thought of as this terrible down death album, because that’s not at all what I mean by it,” Lou Reed said of "Magic & Loss" (1992) to the Chicago Tribune: "I think of it as a really positive album, because the loss is transformed magically into something else." In "Warrior King," Reed channels his anger into a fantasy of omnipotence: "I wish I was a warrior king; inscrutable, benign / With a faceless charging power always at my command / Footsteps so heavy that the world shakes / My rage instilling fear." Reed feels his loss, but has reached a level of acceptance: "My friends are blending in my head / They're melting into one great spirit / And that spirit isn't dead."

Ellen Willis, the first rock critic for The New Yorker wrote “The Velvet Underground” essay, included in fellow critic Greil Marcus’ book “Stranded” (1979). “The songs on ‘The Velvet Underground’ are all about sin and salvation,” Willis begins. The crux of Willis’ essay is that Lou Reed managed to exist in that rare space between irony and sentimentality, to avoid slipping into either the snarl or the smile. His music was an exercise in rejection, but not the knee-jerk anti-establishment hostility. It’s a rejection of rejection, a fight against both the nihilism of punk and the boppy, commercial vibes of pop music. “For the Velvets, the aesthete-punk stance was a way of surviving in a world that was out to kill you,” Willis writes. “The Velvets were not nihilists but moralists.” Willis explains, “Their songs are about unspeakable feelings of despair, disgust, isolation, confusion, guilt, longing, relief, peace, clarity, freedom, love—and about the ways we habitually bury them from a safe, sophisticated distance in order to get along in a hostile, corrupt world. Rock & Roll makes explicit the use of a mass art form was a metaphor for transcendence, for connection, for resistance to solipsism and despair.”

Shelley Albin said about Reed's sexuality: "I think by nature he was more driven to women because of his relationship with his mother. That’s what he thought was normal. It was comfortable.” Reed, Shelley said, was “a romantic at heart. He could be very sweet. He’s probably the only person who ever literally gave me a heart-shaped box of chocolates on Valentine’s Day. But he wasn’t happy unless he made somebody more miserable than he was. Misery made for his best work, whether it came from me or somebody else. He wasn’t anybody I wanted to live with and put up with. It wasn’t worth it. It was too much grief.” As for his reputation as a sexual player, that, too, was something of an image. “I got the impression that he never really had a girlfriend in high school,” she said. “I think he put on an aura later of being a ladies’ man. Hardly at all. That didn’t fit with the guy I met. He didn’t do as much in college as he pretended later. I met him after he’d been at college for a year. He was awkward. Boys I went out with in high school were smoother.” “I liked his brain,” Shelley said. “We could talk for hours and hours, days and days. We connected. He was an incredible romantic. So we connected on that level. It was very much a creative-mind thing. I was crazy about him. He was a great kisser and well coordinated. His appeal was of a very sexy boy/man. Lou was very insecure, and he needed a nurturer.” Lou Reed treated relationships, sex, and masculinity with a sense of simultaneous distance and intimacy. Just as femininity, sex clubs, and drugs were something to look at, so was masculinity. Reed’s explorations of identity evolved from rocker to strung-out junkie to effeminate songster to middle-aged intellectual. Lou Reed's quixotic/demonic relationship to sex was clearly intense. No one understood Lou's ability to make those close to him feel terrible better than the special targets of his inner rage, his parents, Sidney and Toby. Lou dramatized what was in the 1950s suburban America his father's benevolent dominance into Machavellian tyranny, and viewed his mother as the victim when this was not the case at all. The fact is Sidney and Toby Reed adored and enjoyed each other. After twenty years of marriage, they were still crazy about each other." –"Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story" (2014) by Victor Bockris