"The Black Dahlia: she's a ghost and a blank page to record our fears and desires," wrote James Ellroy. "A post-war Mona Lisa, an L.A. quintessential." It's a real-life mystery that's inspired countless moviemakers and writers from "Double Indemnity," "Chinatown" and "L.A. Confidential." One of the most important themes in noir is the confusion of identity. In that sense, "The Black Dahlia" is one of the purest examples in the whole genre. The femme-fatale in the story, Madeleine, identifies with Elizabeth's looks. Lee identifies Elizabeth with his little sister, Bucky sees himself reflected in Elizabeth's personality. Even Kay sees herself dragged in this twisted litany of obsession: "[Lee] loved us. And I love you. And if you hadn't seen so much of yourself in her you'd realize how much you loved me". Bucky has fallen in love with Elizabeth's image: "Bye-bye Betty, Beth, Betsy, Liz, we were a couple of tramps, too bad we didn't meet before 39th and Norton, it just might have worked, maybe us would've been the one thing we wouldn't have fucked up past redemption". This 'death leer', the book's dominating image, joins the comic to the macabre and joy to anguish because of the critical distance it puts between victim and tormentor. [...] great art requires distancing. It's perspective and slant that makes us wonder if Beth, despite the brutal pain inflicted on her by them, didn't get the last laugh on Ramona and Tilden, that sorry pair whose sole claim on our memory comes from their connection with her. Bucky's voice over: "They found him [Georgie Tilden] croaked in a parking lot downtown, just twelve blocks from where he'd dumped Betty Short. Just croaked. I hoped the evil ate him from the inside out, filling him with blackness..." -"Like Hot Knives to the Brain: James Ellroy's Search for Himself" (2006) by Peter Wolfe

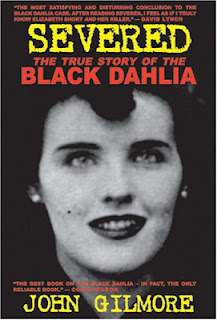

John Gilmore: I met Elizabeth Short in late ’46 when I was 11 years old. Elizabeth Short’s father abandoned his car on the Charlestown Bridge in Massachusetts, and seemed to vanish—to disappear. This was just after he lost his business during the Depression. Phoebe (Elizabeth's mother) worked as a bookkeeper, but for the next four years the family mostly depended on Mother’s Aid and government handouts. Phoebe Short was shocked when she received a letter from Cleo. He said he was in Northern California working in the shipyards, and apologized for leaving the way he did. He tried to explain in the letter that he had not been able to face up to the troubles, but knew that in his absence, if it appeared that he deserted or was dead, Phoebe would be eligible for more support. He asked if she might now allow him to return to the family. Phoebe answered her husband with an emphatic 'no'. She did not consider him her “husband.” Beth met a very handsome Army Air Corps lieutenant, a pilot who had taken her to dinner twice. He had the use of a car and he’d take her to the beach and the amusement pier, or to Knott’s Berry Farm for fried chicken. This sentiment changed on New Year’s Eve of 1945, when flyer Major Matt Gordan stepped into her life. A few days later the major asked her to be his wife. “I’m so much in love, I’m sure it shows,” she wrote to her mother. “Matt is so wonderful, not like other men... and he asked me to marry him.” Phoebe was very surprised with this news, but impressed with the photograph her daughter sent of herself and the handsome pilot. Matt gave Beth a gold wristwatch that was set with diamonds as a pre-engagement gift, and wrote to his own sister-in-law that Beth “is an educated and refined girl whom I plan to marry.”

James Ellroy: The LAPD will not let civilians see the file on the Dahlia case, which is six thousand pages long. When I started working on the novel, I was still living in Westchester County and realized that I could get, by interlibrary loan, the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Herald-Express on microfilm. All I needed was four hundred dollars in quarters to feed the microfilm machine. Man, four hundred bucks in quarters—that’s a lot of coins. I used a quadruple-reinforced pillowcase to carry them down from Westchester, on the Metro-North train. It took me four printed pages to reproduce a single newspaper page. In the end the process cost me six hundred dollars. Then I made notes from the articles. Then I extrapolated a fictional story. The greatest source, however, was autobiography. Who’s Bucky Bleichert? He’s a tall, pale, and thin guy, with beady brown eyes and fucked-up teeth from his boxing days, tweaked by women, with an absent mother, who gets obsessed with a woman’s death. It wasn’t much of a stretch. Source: www.theparisreview.org

Larry Harnisch: Steve Hodel has also returned to his claim that his father “probably” killed Geneva Ellroy, mother of author James Ellroy. Steve Hodel earned a robust, throaty “Fuck You” from Ellroy when he originally floated this nonsense, so although Ellroy had jumped into the Hodel crowd, he has now jumped out, refusing to discuss Steve Hodel or the Black Dahlia. One of Steve Hodel’s more bizarre claims is that when the purported killer of Elizabeth Short called Examiner city editor James Richardson, he identified himself as the “Black Dahlia Avenger.” Of course, that isn’t true. As with so many things, it’s something Steve Hodel would very much like to be true. But it’s not. And the nonsense about George Hodel being a taxi driver and knowing the city of Los Angeles like the back of his hand, including the neighborhood on South Norton Avenue where Elizabeth Short’s body was found. Naturally, Steve Hodel has never actually researched when the neighborhood was developed – or he would know that it didn’t exist when his father was driving a cab. Did I mention that George Hodel’s purported photos of Elizabeth Short aren’t her? So says her family. I may add to this as I find more lies – and these are lies. Steve Hodel knows that these things aren’t true. These aren’t mistakes. These are deliberate misrepresentations and lies. The main thing, of course, is that every bit of Steve Hodel’s investigation is about Steve. Elizabeth Short barely enters the discussion. It is all about Steve Hodel. Source: ladailymirror.com

Larry Harnisch has studied the case off and on for twenty-five years. He has interviewed more than one hundred-fifty people, ranging from the first officer on the scene, to family members of Short, to a former boyfriend, to detectives assigned to the investigation, to the woman who discovered the body. The office in his small South Pasadena home is crammed with five metal file cabinets, twenty boxes of file folders, and four bookcases lined with hundreds of books, all focused on the Short homicide or Los Angeles history. Harnisch is writing a book about the case, but the homicide and the investigation are only part of his focus. His research began when he was a copy editor at the Los Angeles Times and he was writing a 1997 fiftieth anniversary story on the killing. He had so much additional material that when the story ran, he decided to write a book. After three drafts, engaging in countless online battles with people writing about the case whom he constantly fact-checks, and struggling to find a publisher, there are days, he says, when he wished he never heard of the case. He never imagined that he would unearth a murder scenario and a suspect who would intrigue LAPD detectives. “Nobody can tell this story straight.” Harnisch scowls. “Everyone wants to fuck with it.” Some writers claimed she was lured to Hollywood from the East because she was an aspiring actress. She wasn’t. Others wrote that the newspapers gave Short the sobriquet. They didn’t. A few have intimated she was a hooker. She wasn’t. Or that, at the very least, she was promiscuous.

She wasn’t. Some writers contended the original detective team was inept. They weren’t. She’d been called a war widow. She wasn’t. Harnisch is grateful he began his research decades ago, long before the case generated renewed interest in the Twenty-First Century, because many of those he interviewed are now dead. “What keeps me going is that I promised myself I would clear up all the lies and myths and try to reclaim Elizabeth Short from the Dahlia freaks. I feel a responsibility. The family has gone through so much and all writers have ever done is rip them off. They deserve to have somebody tell the story accurately. That’s the least I can do for them and for Elizabeth Short, someone who changed my life.” In the 2001 documentary James Ellroy’s Feast of Death, Harnisch presents his theory of the case during a dinner hosted by Ellroy, who called Harnisch’s theory “the most plausible explanation of the murder that I’ve heard… the theory is great. It’s just about watertight in most ways.” “Everyone wants this to be a noir morality play,” Harnisch says. “The aspiring young actress comes to tinsel town with stars in her eyes and this is what happens to impressionable young women who want to be in the movies. The truth is she came out to Southern California for a man. That’s a lot less glamorous.” Writers have portrayed Short as a promiscuous loser sleeping her way across Hollywood. The truth is, Harnisch says, she was just a young woman traumatized by the death of her fiancée, she was a lost soul. Harnisch anticipates finally finishing his book soon. Source: crimereads.com

Larry Harnisch: "To the people who ask how my Black Dahlia book is going. A snippet: James Ellroy is a wretched human being and a tortured soul. A high-school dropout who tosses around words he's dug out of a thesaurus and belabors and belittles everyone with his "Demon Dog" status. Anyone who isn't suitably deferential will be on the outs with Ellroy in short order. Today, he is coasting on his reputation, slowly sinking into a pool of poisonous thoughts, lazily penning racist, sexist fantasies about an imagined past for a dwindling base of fans who sees his abuse as some sort of genius." Source: Instagram.com

No comments :

Post a Comment