A new intimate memoir by the controversial and outspoken, Oscar-winning director and screenwriter about his complicated New York childhood, volunteering for combat, and his struggles and triumphs making such films as Platoon, Midnight Express, and Scarface. Before the international success of Platoon in 1986, Oliver Stone had been wounded as an infantryman in Vietnam, and spent years writing unproduced scripts while driving taxis in New York, finally venturing westward to Los Angeles and a new life. Stone, now 73, recounts those formative years with in-the-moment details of the high and low moments: We see meetings with Al Pacino over Stone’s scripts for Scarface; his risky on-the-ground research of Miami drug cartels for Scarface. Chasing the Light is a true insider’s look at Hollywood’s years of upheaval in the 1970s and ’80s. It will be released by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (July 21, 2020)

“Everyone got the demon in here,” Mickey says in Natural Born Killers. “It feeds on your hate. Cuts, kills, rapes. It uses your weakness, your fears. We all know we’re no good pieces of shit from the time we could breathe. After a while, you become bad. You know the only thing that kills the demon, Wayne? Love. That’s why I know that Mallory’s my salvation. She was teaching me how to love.” Stone's work and his critiques of the way white men have gone about making this country constantly summon James Baldwin, who wrote, “People pay for what they do, and, still more, for what they have allowed themselves to become. And they pay for it very simply: by the lives they lead.” We see this most glaringly in Stone’s white heroic depictions, like the hero of Platoon, realizing that he has to pick a side and kill the representative of “the machine.” We see this in the hero of Wall Street selling good fathers, including his blood father, to get in good with Michael Douglas. We see it in the hero in Born on the Fourth of July, buckling under a superior officer’s pressure to lie about battlefield atrocities, then rising up years later to oppose the entire war effort.

Stone's greatness is his audacity, which lies partially in his talent as a skilled storyteller, but mostly in his ability to explore and exploit his moral mediocrity while standing utterly unafraid of looking at how bad, bad, bad our nation has made you, him, and me. Although he is in many ways very far left by Hollywood standards, he is also not the most enlightened person when it comes to feminism, race relations, homophobia, and the like. He struggles with terminology, and like most straight men of his generation, he tends to go into a rhetorical defensive crouch when interrogated about his language and beliefs. Here and there you’ll see lines that are redacted instead of deleted. No one will ever know who requested the redactions—a lawyer working for Abrams Books; my editor or a copy editor; Oliver; me—or what, exactly, is hidden under the redaction lines, but I wanted them to have a presence on the page, even if you couldn’t actually read them. You should think of these blackened lines as spirits cut down during the battle to get this book published. In 1969 Stone wrote his first (still unproduced) feature-length script, Break, an expressionistic piece that turned the war into a psychedelic interior journey, equally influenced by European art cinema, and the rock and roll that made life bearable for soldiers in the bush. Stone sent a copy of the screenplay to Jim Morrison, who was eking out his final days in Paris; his favorite sergeant in Platoon Elias, is a Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol infantryman, whom Stone described as having a Morrison-like face and a dreamy, mystic quality.

After NYU, Stone obsessed over the war while he wrote spec scripts, worked odd jobs in the East Coast film scene, and drove a cab at night. In 1976, Stone wrote the first draft of a screenplay titled The Platoon—a more straightforward account of his experiences than “Break,” filled with journalistic details and savage violence, and anchored to a blank-slate hero not unlike Crane’s Henry Fleming. In 1986, Stone finally got to direct Platoon which is set in the sixties, and its story of a young US Army infantryman (Charlie Sheen) morally torn between a stoner Jim Morrison/Jesus figure (Willem Dafoe) and a ruthless leather-faced, alcoholic redneck (Tom Berenger). Chris is noble, naive, doomed: an innocent abroad, coming of age in hell.

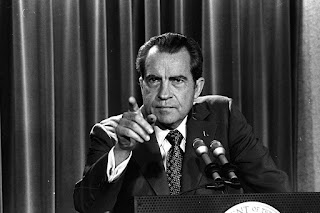

Stone, who sent his first feature-length script “Break” to Morrison right before the singer’s death and modeled Platoon’s Elias on him, has said that The Doors is his fantasy of the rock star as an embodiment of Dionysian fearlessness—a dream figure who carried the emotional arc of the sixties counterculture within him, moving from utopian rebellion and feral boldness to booze-soaked depression, withdrawal, and oblivion. As a film stylist, Stone shares Morrison's interest in breaking away from convention, and at times he frees his movie The Doors from the usual Hollywood formulas, gliding through time and space with exhilarating, psychedelic ease. Stone is less inventive at scene-by-scene storytelling, though. Pamela Courson is depicted as saying hostile things to Patricia Kennealy, when by all reports their interactions were polite. What Stone found particularly compelling about Morrison emerges through such a motif as he studies his hero as doomed not just by internal failings, but also by the specific flaws of his society. Just as much as Nixon represented to Stone both the beauty of America in his capacity to rise from straitened youth to national captaincy—and its dark flipside in his resentment and paranoia—Morrison likewise represents a spiritual America doomed to be tortured by a materialistic age where hedonism is offered as substitute for liberty.

Deleted Scenes on The Doors DVD — These extended scenes are introduced by Oliver Stone who regrets removing some of them from the final cut: Pamela and Jim are on a plane to New York talking about how they would like to die. Another scene showing Ray and Dorothy Manzarek's wedding, followed by Pamela and Jim shopping for their dinner. Also, Morrison in a motel room crying in company of a groupie. What ruined Jim Morrison? The film, at times, dares to make the outrageous suggestion that he died for his audience's sins. One of Mr. Stone's most effective tricks is to fade out the sound entirely at one crucial moment, as Morrison becomes fatally out of touch with his audience. Perhaps Morrison is symbolic of the death of the artist in a society bent on war and destruction.

—Steve Wheeler: What are your thoughts about the Stone movie?

—Frank Lisciandro: "I found it to be intolerable. Oliver Stone did not want to know who Jim Morrison was and he did not come close to capturing the essence of Jim. The film never presented the quiet, sensitive, extremely intelligent human being that Jim was. He wasn’t frantic and manic as he is portrayed in this movie. Jim had a sensational sense of humor and that is what is entirely lacking in the Stone film. The guy was hilariously funny and he would make himself the butt of jokes. I never saw Jim lock someone in a closet and set the room on the fire. I couldn’t even imagine him doing anything remotely like that; this was absolutely not in his nature or personality. He was not a violent person. If Jim needed to get back at you, he would do it with words, and he could be devastating that way. Jim loved to laugh and he was not shy about laughing at himself either. He had such humility that he would do that. Yes, he did some crazy things on occasion, but he was also a warm and sensitive person a vast majority of the time. There’s a balance that you don’t find in the movie and that imbalance totally eliminates the real Jim Morrison from the screen.”

—Steve Wheeler: We did interviews with Morrison's closest friends, bandmates, managers, and others over the years. People thanked us very much for searching and exposing the truth, and not the usual unrealistic, ignorant, garbage gossip people are presented 99% of time. I do find it sad that Stone refused to show any of Morrison's good sides. Even Danny Sugerman, not one to shy away from spewing myths and salacious rumors about Morrison, admitted: “It’s Oliver Stone’s version of Jim. There is some truth within it, but it’s not the truth, and it contains numerous fictionalized accounts and considerable exaggeration.” Robby Krieger: “Oliver was only interested in the self-destructive, brooding personality so he was focusing on that aspect of Jim. We were always complaining that the script was too dark, and that’s why Ray bailed on the movie. Oliver did make Jim into a caricature. I mean Jim could be a little freaky from time to time, but not all the time like the movie would have you believe.”

Jim Morrison: “The answer is never the answer. What's really interesting is the mystery. If you seek the mystery instead of the answer, you'll always be seeking. I've never seen anybody really find the answer. They think they have, so they stop thinking. But the job is to seek mystery, evoke mystery. The need for mystery is greater than the need for an answer."

Jim Morrison: “The answer is never the answer. What's really interesting is the mystery. If you seek the mystery instead of the answer, you'll always be seeking. I've never seen anybody really find the answer. They think they have, so they stop thinking. But the job is to seek mystery, evoke mystery. The need for mystery is greater than the need for an answer."

"Yeah, I missed out on the sixties," Stone admits. "I'm not angry about it, but I am saddened that I missed it—especially the healthy male/female relationships. I never had a coeducational existence. The sixties had this enormous sense of sexual liberation. Women started to come out of the closet and fucking was 'in'. It was stylish, fashionable. I missed all that, and the honest, open man/woman communication that came with it." Stone saw Jim and Pam's relationship as a great love story: "She may be basically a figure of innocence, but I see the movie character of Pam as a monster, too. She's very much a sixties child, not too thoughtful, not too intelligent. She decides to ride the snake with Jim, she can hold on and stay with him all the way out—till the point where she's willing to die with him. What I like in their story is that Jim had this loyalty, too. He stuck with her to the end. That's at the center of the movie. He really loved her. Morrison was even darker than we showed in a lot of ways—what struck me was his sadness and depression. I couldn't find the exact Jim. He's an enigma. Nobody could play Jim Morrison but Jim Morrison." —"Oliver Stone: The Controversies, Excesses, and Exploits of a Radical Filmmaker" (1995) by James Riordan

“Part of what made it easy to play Jim was that he was a brilliant actor. He acted a lot. He didn’t want people to know him and he presented something which prevented you from getting close.” -Val Kilmer

We're reaching for death on the end of a candle. We're trying for something that's already found us. Everything human is leaving her face. Soon she will disappear into the calm vegetable morass. Stay! My Wild Love! Earth Air Fire Water. Mother Father Sons & Daughters. Airplane in the starry night. First fright. Forest follow free. I love thee. Watch how I love thee. Shake dreams from your hair. My pretty child, my sweet one. Choose the day and choose the sign of your day. A vast radiant beach in a cool jeweled moon. And we laugh like soft, mad children. The time has come again. Choose now, they croon. Beneath the moon. Enter again the sweet forest. Enter the hot dream. Everything is broken up and dances. Your milk is my wine. My silk is your shine. —Wilderness (1971) by Jim Morrison

Ray Manzarek: A lot of people didn’t care for Jim’s shades back in the day. My wife complimented him on them and he seemed stunned. He told her “Pam thinks they look too far out there.”

Alan R. Graham (ex-husband of Jim Morrison's sister Anne): Pamela Courson was so very close to Jim Morrison from the beginning because of her love for his poetry. She told him he was a real poet before anyone else did. In return for her love and nurture, Morrison let her deep inside of his heart. He needed this kind of love badly.

-Matt Zoller Seitz: Do you see a connection between The Doors and Natural Born Killers?

-Oliver Stone: Yeah, I think of it as a line. Filming Natural Born Killers was like being free again. I think The Doors is like Natural Born Killers. It’s in that line of film where with imagery we freed ourselves and allowed free associations. I rewrote Randall Jahnson's script. My concept was to set the story to the songs. The song would set the scene, like we did later in Natural Born Killers. There’d be a song that’d be the mood, and it was written. I'd sent Morrison a script of Break, which was my first script which I wrote when I came back, about Vietnam. It was very psychedelic. I thought Jim could play the soldier. He could play the character of me. It was quite a wild script. I didn’t hear back, of course. I’m used to that, I’ve been rejected before.

-Oliver Stone: Yeah, I think of it as a line. Filming Natural Born Killers was like being free again. I think The Doors is like Natural Born Killers. It’s in that line of film where with imagery we freed ourselves and allowed free associations. I rewrote Randall Jahnson's script. My concept was to set the story to the songs. The song would set the scene, like we did later in Natural Born Killers. There’d be a song that’d be the mood, and it was written. I'd sent Morrison a script of Break, which was my first script which I wrote when I came back, about Vietnam. It was very psychedelic. I thought Jim could play the soldier. He could play the character of me. It was quite a wild script. I didn’t hear back, of course. I’m used to that, I’ve been rejected before.

-Matt Zoller Seitz: So he never contacted you?

-Oliver Stone: No. He died in ’71, so that would’ve been probably two years after I wrote the script. I thought Jim was serious, almost suicidal, all out for nothing. I think you see it in the movie, he takes no prisoners. ‘Do you love me?’ ‘Would you die for me?’ It’s crazy stuff. When he left LA for Paris, he was finished with the band. I do think Paris was the beginning of a new stage but it got derailed. I think part of that, this is my opinion only, I can’t prove it, but I do feel that Pamela Courson had a drug problem. My feeling is that he was trying to help her, and kept up with her, and I think he overdid it. We weren’t allowed to depict her addiction, because her parents didn’t want to have any of that, but you can see in the film that she’s high. I actually had access to 120 transcripts through the kindness of Jerry Hopkins, who had collected them. But Manzarek, who I don’t believe ever saw Hopkins’ transcripts, was outrageous in what he said, and totally mean-minded. But the thing that really bothers me is that Manzarek, if you really go over Hopkins’s transcripts, doesn’t figure prominently, except as a musical coworker. He’s Jim’s colleague and all that, he's very important at the beginning, but after the first album you sense Manzarek was a complete opposite to Jim. Everything with Jim was freedom; Manzarek is control. Manzarek is the authority figure. Jim never really had a social life with Ray anyway. Manzarek was like an Iago figure to me. I probably made Morrison more dangerous than he wanted him to be, but I read those transcripts: what was going on sexually, his impotence, all kinds of issues.

-Oliver Stone: He was an alcoholic with a capital A and he wasn’t that sex-driven as much as he was this idea of sex, and you know, Pamela’s a pretty straight woman, kind of boring in a way, [Redacted] But in other words, I don’t see Pamela as some exotic hippie chick. So Meg Ryan was not bad in the part, although she’s strange somehow. Pam Courson was a strange lady, but I find her to be kind of bland, and I think Jim liked that quiet quality of her. I think he was so outrageous that he wanted the opposite. In the film it wasn’t the way Pam really was, but she would probably be happy with Meg. I think we got away with Meg Ryan. Val Kilmer told me—he broke my heart—at the end of the shoot, he said, "You don’t know how to direct" at the last wrap party. —The Oliver Stone Experience (2017) by Matt Zoller Seitz