‘I’m literally Joan Baez right now’: Gen Z women relate to Bob Dylan’s toxic situationship: Joan Baez met Bob Dylan at Gerde’s Folk City, a Greenwich Village venue, in 1961, when she was a bonafide star and he was new to the scene. They became creative partners, with Baez believing she inspired Dylan classics such as Visions of Johanna and Like a Rolling Stone. Dylan ended the relationship in 1965 as he shot into superstardom, and Baez has since forgiven him: “We were stupid, and you can’t blame somebody for ever. I certainly tried but finally stopped.” Now 84, Baez has emerged as the unlikely hero of A Complete Unknown: yet another woman who stepped out from the shadow of a guitar-playing alt boy. Another woman analyzes their Newport performance of It Ain’t Me Babe, when Baez and Dylan shared the microphone. “Whenever I see this video of Bob and Joan it lowkey fills me with annoyance. I’ve always loved him but ever since watching the biopic it’s like sir why are you screaming over her.”

One counterpoint, per a comment: “that’s just how he sings I’m afraid.” Stephen Petrus, a scholar of 1960s folk music and director of public history programs at LaGuardia Community College, believes that gen Z is “expressing solidarity” with Baez online. “I think there was a sense of mutual opportunism between the pair,” he said. “But Dylan was not always kind to her, and he wanted to be the dominant one on stage, which is pretty clear both in the movie and certain performances.” Diamonds and Rust was the 1975 confessional Baez penned about her relationship with Dylan. For a generation accustomed to modern dating drudgery, lyrics like “Well I’ll be damned / here comes your ghost again” still hit. Source: www.theguardian.com

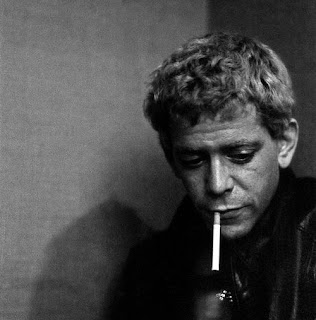

‘I’m not in this game for the money or to be a star,’ Lou Reed insisted early on. Of course, all rock stars said that, early on, when they were striving for money and stardom. Lou Reed actually meant it. It was, perhaps, the most truthfully shocking thing about him. Reed grew up playing high-school baseball and taking classical piano lessons. Although he later complained about his musical education (‘I took classical music for fifteen years – does that make me legitimate?’) it left him with an impressive grasp of musical theory and composition and ‘a natural affinity for music’. By 1959, Sidney could stand it no longer and made arrangements to have his terrified but still defiant son admitted to Creedmore State Psychiatric Hospital, a state-run facility housing more than 6000 patients. For the next eight weeks, Reed underwent hour-long bouts of ECT. It was a devastating experience that would stay with him, mentally and physically, for the rest of his life. The adult Reed would recall with disgust ‘the thing down your throat so you don’t swallow your tongue’. The electrodes methodically attached to his head, held in a brace. His juddering body strapped tight to the bed.

He was eventually put on a tranquilliser, Placidyl, and would continue to take a daily dose for several years. Known on the street as ‘jelly bellies’, it became a contributory factor in the deadpan expression Reed was to assume for the rest of his life. He also began having weekly sessions with a psychiatrist. It could be argued Reed never stopped writing about the therapy that nearly robbed him of his mind. That he would never forgive the ice-cold father who put him in the ward or the ruthless doctors who performed the ‘therapy’ upon him. That he would never trust anyone again until his life was almost over, throwing up a shield that only the similarly damaged could ever truly see through.

When John Cale married Betsey Johnson in April 1968, it drove a further rift between him and Lou. Many assumed Lou was so deep into his drugs and his musical trip that he simply had no time to love anybody but himself. It wasn’t true. In fact, Lou was secretly seeing his old flame from Syracuse, the beautiful Shelley Albin. Shelley was now married and had moved with her husband to New York in 1966, since which time Lou and she had begun seeing each other again but only – much to Lou’s disappointment – as ‘good friends’. By 1968, however, the rumour was that this friendship had blossomed once again into a full-blown love affair. Certainly, Lou would claim so, to friends, and by mentioning his love for someone who was married in Pale Blue Eyes. ‘Lou and I connected when we were too young to really put it into words,’ Shelley would recall years later. But, though she loved his fierce intelligence, his flare for the extraordinary bon mot or surprisingly romantic gestures, Shelley had always been wary of what she saw as his ‘crazy side’. And the more he begged her to leave her husband and come and have a real life with him, the more she shrunk from the idea. No matter how hard he implored, accusing her of choosing ‘security’ over ‘love’, Shelley refused to leave her husband.

The first solo album of Lou Reed (1971) was produced by Richard Robinson for RCA Records. At the insistence of Reed, the cover was designed by Tom Adams, a former illustrator of Raymond Chandler's paperbacks, featuring a forlorn chick looking parentless and doomed. This album bombed in USA and also in the UK. In fact, without the intervention of David Bowie, it seems highly unlikely that Lou Reed would ever have had a career. The two had finally met for real in September that year, when Bowie was flown into New York to great fanfare, in order to celebrate his signing to RCA. Dennis Katz, via Richard and Lisa Robinson, brokered the meeting, organising a party at the Ginger Man, around the corner from Madison Avenue. Lou turned up with Bettye and David showed up with Angie.

Tony Zanetta had bonded with David and Angie in London, and nervously affected introductions. Despite of Nick Tosches having remarked that hordes of girls would never have pursued Lou Reed and John Cale like all the girls who went hysterical for The Beatles, Bowie, however, expressed to Melody Maker that for him "The Velvet Underground talked to me more than the Beatles ever did. For me, Lou Reed is the greatest songwriter in rock and roll." The Robinsons felt that they had brought Lou out of retirement and saw his alliance with Bowie move as the ultimate betrayal. After the breach when they weren’t speaking, Lou would say of the Robinsons: ‘They’re little pop people.’ To promote their new star, Reed had fashioned himself in the image of what his English fans imagined he was—a junkie hustler.

However, Andy Warhol, a man with a telling eye for these things, pointed out, “When John Cale and Lou were in the Velvets, they really had style. But when Lou went solo, he started copying other people.” The figure he presented to the public didn’t really exist. Lou didn’t shut up, his insecurities raging as he confronted the English star he’d been told had been featuring Velvet Underground songs in his set, and who he was now connected directly to through their shared relationship with RCA and, specifically, its vice-president of A&R, Dennis Katz. Bowie for his part remained relatively quiet, overwhelmed by the force of the always heavily loaded New York conversation, not sure who was putting who on, or who was being put down. While Angie Bowie, of course, could match Lou or anyone else for fast-track trash talk, NY-style. Bettye, meanwhile, sat quietly, obediently, in her pants suit, looking like ‘an airline stewardess’. Lou, for his part, hardly looked like the hip young former Factory imp that Bowie had been expecting. While David was going through his ‘Lauren Bacall phase’, his blonde hair long and swept over one shoulder, his eyelashes fluttering under the weight of heavy blue shadow, Lou had turned up looking like the guy who came to fix the plumbing; dressed down in head-to-toe denim, paunchy, his hair cut almost Army short.

As Angie wrote in her autobiography: "David always had that knack of looking you in the eye and making you feel you were his only priority at the time. I think David saw Lou and to a lesser extent Iggy as his competition, and his master game was to drag them to his dominion and try to neuter them in some capacity." Leading the backlash in Britain was the NME, whose Charles Shaar Murray characterised Transformer in his review as ‘a collection of songs witty, songs trivial, songs dull, songs sad, none of them really much cop’. It was in America, though, where Lou and Bettye returned home, in time for its release, that the knives were really out. The New Yorker called the album ‘lame, pseudo-decadent lyrics, lame pseudo-something-or-other singing, and a just plain lame band’. Henry Edwards also panned the album in the New York Times. So it was that Lou Reed began recording the album Berlin, that would both become his masterpiece and effectively end his career as a major recording star at that time. Considering where Lou Reed had spent his entire musical career – in the backrooms of the music biz, making records for the doomed to gaze at their reflections in – the subject matter of Berlin is arguably in keeping with the arc of his own artistic narrative. Yet considering he was now coming off the back of a bona fide worldwide hit, it’s staggering how prepared he was to risk it all for an album, masterpiece though it is, as profoundly disenchanted as Berlin.

That while shrewd David Bowie was busy releasing crowd-pleasers like Aladdin Sane, Lou Reed would almost deliberately sabotage his own career in the name of what? Art? Arrogance? Disdain? While in Creem magazine, Robert Christgau refused to be shocked, just merely "too bored to puke at it." He said that the story was lousy and ‘coughed up by some avant-garde asshole’ and he gave it a C. In response, sales were abysmal. Recorded at New York’s Bottom Line club in May 1978, and featuring a superbly splenetic Lou Reed in absolutely blistering form, Take No Prisoners was the live summation of everything the post-Velvets Lou Reed had become. Before the band comes absolutely smashing into the riff of ‘Sweet Jane’, which then goes on for over eight minutes as Lou digresses again into the kind of backstories that future MTV-style story-behind-the-song programmes could never hope to match, including how much Lou hates ‘fucking Barbra Streisand’ for thanking ‘all the little people’ in her Academy Awards. From there the album takes off into something that is part rock’n’roll, part Lenny Bruce comedy act, part confessional, part pure confrontation. ‘Hey, shut up!’ when someone interrupts his flow. ‘Are you fucking deaf?’ at another juncture. A weird musical milieu where ‘I Wanna Be Black’ is suddenly hilarious and self-mocking: ‘Let’s ask the chicks…’ Where ‘Satellite Of Love’ and ‘Pale Blue Eyes’ are soulful and wincingly revealing, played virtually straight. ‘So now everybody’s gonna say Lou Reed’s mellowed, he’s older. He didn’t act mean, he talked. Oh boy. I say we’ll mug you later, all right? You feel better?’

Along the way we are treated to some more classic asides: ‘I do Lou Reed better than anybody else, so I thought I’d get in on it,’ he announces to braying laughter. ‘Hey, watch me turn into Lou Reed!’ He also takes the opportunity to mock his critics, raging at Robert Christgau, calling him ‘a toe fucker’ for his pathetic A, B, C ratings system, telling on John Rockwell of the New York Times, who ‘comes to CBGBs with a bodyguard’. Back home in New York, when pressed whether it was true he had actually hit David Bowie, an unrepentant Lou snapped: ‘Yes, I hit him – more than once. It was a private dispute. It had nothing to do with sex, politics or rock’n’roll.’ That he had ‘a New York code of ethics’. He scowled. ‘In other words, watch your mouth.’ Word eventually crept out though that the basis of Lou’s rage was in David’s response to Lou’s only-half-joking inquiry about whether he would like to produce Lou’s next album. When Bowie answered in the affirmative, but only on condition that Lou ‘clean up his act first’, Lou went insane. His second wife and manager Sylvia would occasionally accompany Lou on his tours, but mainly her role would be as the traditional homemaker. According to Lou, “Sylvia’s very, very smart, so I have a realistic person I can ask about things: ‘Hey, what do you think of this song?’ She helped me so much in bringing things together and getting rid of certain things that were bad for me, certain negative people. I’ve got help, for the first time in my life. And that’s a real change. I don’t know what I would have done without her.”

As Lou told one reporter a couple of months after the wedding: ‘I now know that certain things will get taken care of and looked out for on the home front… I’ve found my flower, so it makes me feel like a knight.’ There was a temptation for those that had followed his career for longer than 15 minutes to treat such quotes as the further stoned ramblings of an arch-deceiver. But this time Lou actually meant it. Opening with the spellbinding ‘My House’, a hymn to his and Sylvia’s new life at the farmhouse in New Jersey, underneath there was a startling evocation of his old friend and ‘the first great man I ever met’, Delmore Schwartz. ‘My Dedalus to your Bloom,’ he almost weeps, ‘Was such a perfect wit…’ Dissolving into the next track, ‘Women’, a subtle, joyous, almost unbearably straight-talking paean to Sylvia and to the whole concept of womanly love, something Lou had never fully embraced since he’d been a boy, wrapped tight in the arms of his former beauty queen mother Toby. Opening with the rockabilly pop ‘I Love You Suzanne’, a hit single for anybody else, a total flop for Lou Reed, New Sensations was so listenable that attracted the attention of an advertising agency executive, Jim Riswold, then chief copywriter for the Madison Avenue's Wieden & Kennedy. As Sylvia approached thirty, she told Lou the time had come for them to have children, characterizing it as a great adventure. Lou, however, saw the question of children through realistic eyes. Stated one friend, “There’s no way Lou would ever have children, he’s the archetypal constant child. At least he can admit that it would be a big disaster if he had children.“

Then Lou met Laurie Anderson. Ironically, the impending collapse of Lou’s marriage did not do him any harm on the professional front. By the time Lou completed work on Magic and Loss, he and Sylvia had begun to talk about getting a divorce and consulted their respective lawyers. Sylvia knew she was going to be comfortable financially—Lou’s financial situation had changed for the better since they had joined forces and even he openly credited Sylvia for this—but the realization that she was going to lose the glamour and drama of being Mrs. Lou Reed weighed upon her. Meanwhile, her lawyer advised her not to move out of their Upper West Side apartment because that would put her in the position of desertion. “He’s got an image to keep up,” said a friend. “Beyond the fact that he’s thinking, ‘God, I’m alone, I’ve got to find somebody else.’ I’m sure in the middle of the night, that’s the reason he calls Sylvia, because that’s when it hits him—‘Oh my God, I’m by myself.’ That picture of him on the cover of Vox [in May 1993] was so awful. He looks like a ghoul. You heard this thing about his liver.

I’m surprised he’s still alive.” For the most part, the positive chemistry of the former Velvet Underground members overcame their collective fear, and Sterling and Moe worked as a buffer between Lou and John. In fact, the reunion might have been a great success if it hadn’t been for the added pressure of Sylvia, whose ego had ballooned out of proportion. According to several people involved with the shows, Sylvia made no secret of her contempt for John, whom she called stupid and untalented. John was convinced that Sylvia had learned everything in this department from Lou, but others were not so sure. She virtually showered contempt on Cale, going so far at one point as to make the curious remark that as he had grown older John had become exceedingly ugly while Lou had grown more and more handsome. Sources: Transformer (2014) by Victor Bockris and Lou Reed: The Life (2017) by Mick Wall

.jpg)

No comments :

Post a Comment