Megan Abbott on Zodiac: I’ve long wrestled with serial-killer movies, a genre historically fraught with issues of gender and power. For every American Psycho, with its wildly subversive take on toxic masculinity and capitalism, or for every Dressed to Kill, with its twisty, provocative deconstruction of sex and the body, there are countless others that are queasy, underdeveloped, exploitive, tedious. But one of the greatest riches of David Fincher’s extraordinary 2007 film Zodiac is how little gender and sex matter in traditional ways. The Zodiac’s victims were both men and women: a pair of couples, a lone cabbie... The murders aren’t sexualized in obvious ways. Their horror emanates from a place that seems, somehow, at least in Fincher’s parlance, beyond or before sex. A heart, Zodiac is not a serial-killer movie. It’s about our relationship to darkness, our attraction to it, our obsession with the shadowy unknown. “I need to know,” Graysmith says at one point, exhausted and baffled by the depth of his own obsession. In its final, shattering moments, the movie teeters perilously close to a solution, a confirmation. But Fincher is after a far deeper truth than identifying a killer. Solving the crime would provide momentary satisfaction, but the void it would create is too terrifying to ponder. Obsession—perpetual, inexhaustible—keeps alive the possibility of a deeper logic, a sane world, satisfying answers, closure. On some level, you don’t really want to know the truth, because if you did, it would be over and you’d have to face a larger truth—that the darkness isn’t just out there, and spreading. It’s inside you. The virus is you. Source: www.criterion.com

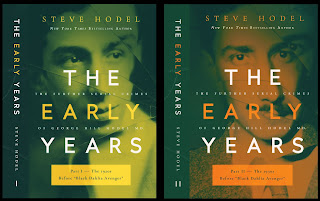

Steve Hodel takes great offense because he believes that Larry Harnisch has been “misinforming his readers.” Hodel portrays himself as a man who cares about the truth and cares about getting his facts straight, yet the facts paint a very different picture of Steve Hodel. Months ago, I posted by my review of Hodel’s book Most Evil. In that review, I proved, beyond any doubt, that virtually all of Hodel’s Zodiac-related claims were 100% false. Most of Hodel’s bizarre solution to the Zodiac case is based on geography and geometry, and I proved, again, beyond any doubt, that virtually all of Hodel’s presentations were inaccurate on both counts. Hodel continues to claim that this already-debunked material is still valid, going so far as to boast of his PowerPoint presentations and continuing to post the same material on his site as if it were factually accurate. An examination of Hodel’s “message” in Most Evil and on his website proves that his work is consistently inaccurate and his claims are easily debunked. One of Hodel’s recent blog entries featured his already-debunked presentations as if they are still valid. Source: zodiackillerfacts.com

Nightmare Alley (2021). Like a stage magician, writers can take advantage of the way we think to keep us looking in one direction while important things are happening somewhere else, burying plot-critical information where it can be uncovered later, without drawing your attention to its significance too early. The hold that stories naturally have on our attention and imagination helps the process along. The psychologist Melanie Green and her colleagues have found that people are more open to persuasion as a function of what they call ‘narrative transportation’. When a story is gripping, vivid, engaging and immersive, we are less on guard, less concerned about whether all the details add up, and more willing to follow a narrative wherever it wants to take us. In the 1970s, the psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman observed that people often take an approach to reasoning that can be described as ‘anchoring and adjustment’. Presented with some piece of information – the asking price for a condo, early results from exit polls, a sample answer to a trivia question – people tend to use that information as a starting point in formulating their own estimates, hypotheses and predictions.

Nightmare Alley (1947). Characters make particularly useful vessels for misleading information, because they add deniability. A character can lie or be mistaken without making the story as a whole inconsistent or dishonest. This handy fact works nicely with another predictable feature of human cognition: our relatively bad memory for source information. Especially if we’re distracted (say, by some compelling, emotionally engaging story content), we can encounter claims in dubious settings, or even see them being debunked, but later remember only that we’ve heard them somewhere before. Then if we encounter the claims again, that sense of familiarity can make us more likely to take them seriously. The psychologist Daniel Schacter, a major figure in the cognitive and neurological study of memory, calls this failing and others like it the ‘sins of memory’, and stories can use them to plant information in places where we are likely to remember the misleading bits while losing track of the caveats. Fortunately, despite our tendency to lose track of this information, we never fully lose track of the distinction, so if a story shows us that a source we trusted was unreliable, we get it. The source is blown, but the story itself can still be on the up-and-up. The con artists in The Big Con (1940) are fond of the maxim ‘You can’t cheat an honest man.’ That claim holds true for some kinds of confidence tricks, perhaps. It’s also a nice thing to tell yourself if you happen to cheat people for a living.

Erving Goffman, one of the most prominent sociologists of the 20th century, wrote his classic essay ‘On Cooling the Mark Out’ (1952) drawing on David Maurer’s The Big Con (1940). Maurer’s account of the later stages of a big con: the first work of grifters is to identify a target, or mark, and gain his confidence. Then the mark can be roped into the criminals’ fraudulent scheme, drawn further in with some small successes, encouraged at last to make a really large investment, and fleeced accordingly. But simply getting the mark’s money is not enough. ‘Suspicious marks are not unusual,’ Maurer reports; ‘in fact all marks are suspicious at first.’ The skilful cooler pours oil on those troubled waters, redirecting, mollifying, distracting and reassuring as needed so that, when it is time to make the big play, the mark goes quietly and willingly, a lamb to the slaughter. As a sociologist, Goffman points out that even though it’s pretty rare to be the victim of a big con, social life is full of people in need of cooling out. Any time someone is ‘caught out on a limb’, when their expectations are dashed and they feel that their status is precarious and their fate is threatened, there is a crisis. If not pacified, they could make a scene, file a lawsuit, or otherwise lash out and spin out of control. Behavioural economists Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein and Martin Weber called ‘the curse of knowledge’: once we know something, it becomes impossible to fully remember or imagine what it is like not to know it. Our earlier selves seem gullible and stupid by comparison. How could we have failed to see what was coming? When we have this reaction to a story, it makes the plot seem brilliant and revelatory. When we have it to events in our own lives, we are more likely to feel guilty and ashamed, culpable in our own downfall. When a story serves up a convincing surprise, we get to have an epiphany about a deeper, truer interpretation of what went before. Source: aeon.co

While his name is likely derived from Charles 'Tex' Watson, Dr. Charles Montgomery’s character most similarly resembles the story of Dr. Walter Bayley, a prime suspect in the murder of the real-life Black Dahlia, Elizabeth Short. Dr. Bayley became a popular suspect long after the initial Black Dahlia investigation. The doctor was a surgeon who lived one block from where Short's body was found; furthermore, after his death, an autopsy revealed he had been suffering from a degenerative brain disease, which could have caused sudden violent behaviors. A popular aspect of this theory is the belief that he had performed illegal abortions, and that he was angry with Short for lying about having a dead son because he had tragically lost his own son years earlier. Considering the fictional doctor performed illegal abortions, and was traumatized by the death of his young son, it’s clear that Charles Montgomery is based on the real-life Dr. Bayley. Dr. Charles Montgomery’s plotline also shares similarities to the real-life case of the Lindbergh baby kidnapping. In March 1932, Charles Lindbergh, Jr. was kidnapped from his crib on the upper level of their home. Over two months later, a truck driver found the infant’s body on the side of a road. In Murder House (2011), Charles and Nora’s son Thaddeus is kidnapped from his upper-level crib by the boyfriend of one of Charles Montgomery’s patients, who then dismembered the baby in revenge. Source: screenrant.com

BLACK DAHLIA, RED ROSE - The Crime, Corruption, and Cover-Up of America’s Greatest Unsolved Murder (2017) by Piu Eatwell: “Nobody had expected her to be so sullenly beautiful,” says Eatwell, who speculates that Elizabeth Short’s striking beauty—which inspired the infatuated press to call her “The Black Dahlia” (“evocative of an exotic flower, of desire both toxic and intoxicating”)—prompted her enduring legend. Piu Eatwell's zealous efforts to solve the case and name the killer (in her view, Leslie Dillon) are less than convincing, but her immersive style is filled with camera-ready period detail. Leslie Dillon was an aspiring screenwriter who was both a former mortician's assistant and a bellhop. Dillon entered the investigation by reaching out to Dr. De River about the case. Dillon claimed a friend of his could have killed Elizabeth Short. De River thought it was a smoke screen and that Dillon may have actually killed Short. Source: nytimes.com

Elizabeth Short was a 22-year-old Boston native committed to being married, her fiancé being killed during the Second World War. Grieving, accounts tell of Elizabeth falling in with dodgy characters as she sought to stay in LA. She variously rented a room behind the Florentine Gardens nightclub and equally had been forced to stay with others at the Chancellor Hotel on Cherokee Avenue in Hollywood. Red Manley was the last person seen in Short’s company, having dropped her at the Biltmore Hotel. Short had told Manley that she was meeting her sister there, but this was a lie, some speculating she may have been meeting another man or simply wished to be rid of Red Manley's company. Manley had been discharged from the army for mental instability and complained that he heard voices in his head. Despite this, Manley had a watertight alibi for the time of Short’s murder and successfully passed two separate polygraph tests. It seems evident that her killing had a profound effect on him, and he was committed to the Patton State psychiatric hospital in San Bernardino in 1954.

Seeking to keep the sensationalism going, the Examiner and other newspapers such as the LA Times needed to one-up the Herald-Express and began to add hints of sex and scandal, suggesting that Elizabeth Short had been a victim of a “sex fiend.” The claims not only hindered the investigation but left a lasting legacy with some still contending to this day that the victim had worked as either a high-class escort or prostitute. There is no evidence for either. On January 17, the Herald-Express first referred to Short as “The Black Dahlia,” a nickname she’d acquired at a local drugstore. Upon investigations, it was revealed that Short had stayed with Mark Hansen before her death, and he quickly became the new prime suspect in the murder despite the fact he would have been unlikely to send the press an address book with his own name on it. Legend tells of how this address book was full of Hollywood names. But this was fiction, and Hansen would later tell police he had given Short his address book as a gift. The nature of that relationship has come under much scrutiny over the years. Hansen had owned several theaters, two boarding houses, and he was a part-owner of the Florentine Gardens nightclub on Hollywood Boulevard. Short had lived with Hansen in October of 1946 and ten days in November. Hansen eventually asked her to leave because of what he saw as her undesirable associations. Some have claimed that Hansen and Short were romantically involved, while others as Elizabeth's close friend Ann Toth contend that she had rejected his advances.

Others suggest that she had “led on” the businessman, angering him when she made it clear she wasn’t really interested. Yet others suggest that there was nothing between the two, and Hansen had merely allowed a lonely woman to stay at his home, being worried about the characters surrounding her. The various versions of the truth are standard with the Black Dahlia case, with much of the evidence convoluted and contradictory. Running a successful nightclub in 1940s LA likely meant that not all of Mark Hansen’s activities were entirely legitimate. Yet, there is nothing to suggest he possessed the level of psychosis attached to the Black Dahlia killing. He had no record of violence in his life and, by all accounts, had felt genuinely sorry for Elizabeth Short and concerned for unnamed associations she was involved with. Having dismissed Manley and Hansen as suspects, police eyes turned toward doctors and medical students. This was both the view of the LAPD and the FBI, with lead investigator Harry Hansen saying that the killer was a “top medical man” and “a fine surgeon.” Police thoroughly investigated medical schools in the area, including the University of Southern California Medical School, located a few miles from the dumpsite. Carrying out extensive background checks, nobody raised any red flags, except Dr. George Hodel for a while.

However, George Hodel wouldn’t be the last physician to be linked with the case. Mainly proposed by LA Times copy-editor Larry Harnisch, Dr. Walter Bayley was a surgeon who lived a mere block south of the lot where Elizabeth Short’s body was found. He had left his wife in October of 1946, just months before the killing, and Dr. Bailey had possibly known Elizabeth Short, being his daughter Barbara a close friend of the Dahlia’s sister, Virginia. While Dr. Bayley had no history of violence or criminality, following his own death in 1948, it was revealed he’d been suffering from a degenerative brain disease. This disease may have made his behavior erratic, with the condition known to cause violent behavior in normally calm individuals. Source: medium.com

No comments :

Post a Comment