-"You can't tell about your life until you're all through living it" -John Garfield as Joe Morse in "Force of Evil" (1948)

-"You can't tell about your life until you're all through living it" -John Garfield as Joe Morse in "Force of Evil" (1948) "The past rears its ugly head", people often say. For me the past isn't so ugly so much as it's sad: sad to have been robbed of my father, the charismatic movie star, at the age of seven, sad that my father died of a massive heart attack at the ripe old age of 39 years -it was more like an attack on his heart, by his own country and by his own friends, including those he had most revered: the Kazans and the Odets, the ones who betrayed their own kind to save their careers.

"The past rears its ugly head", people often say. For me the past isn't so ugly so much as it's sad: sad to have been robbed of my father, the charismatic movie star, at the age of seven, sad that my father died of a massive heart attack at the ripe old age of 39 years -it was more like an attack on his heart, by his own country and by his own friends, including those he had most revered: the Kazans and the Odets, the ones who betrayed their own kind to save their careers. My father's ghost comes back to me when I meet people who say "I knew Johnny", even though I know they didn't because nobody who really knew him called him anything but Julie. I've kept him as a God because I need to, but -in his integrity, in his refusal to name names- was he not godlike? How many could have held out like he did? Could I have?"

My father's ghost comes back to me when I meet people who say "I knew Johnny", even though I know they didn't because nobody who really knew him called him anything but Julie. I've kept him as a God because I need to, but -in his integrity, in his refusal to name names- was he not godlike? How many could have held out like he did? Could I have?" -Foreword by Julie Garfield (John Garfield's daughter) for Robert Nott's book "He Ran All the Way: The Life of John Garfield" (2004)

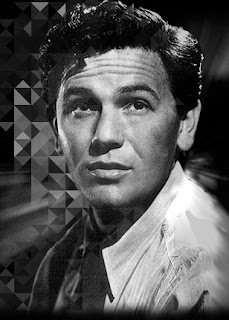

John Garfield was the first actor to play characters who somehow managed to lose even when they were winning. He is generally considered to be the first "rebel" actor in film history; the one who opened the door for all the other cinematic anti-heroes: Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, Robert De Niro and many others walked through that door; somehow Garfield became obscured by it.

John Garfield was the first actor to play characters who somehow managed to lose even when they were winning. He is generally considered to be the first "rebel" actor in film history; the one who opened the door for all the other cinematic anti-heroes: Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, Steve McQueen, Paul Newman, Robert De Niro and many others walked through that door; somehow Garfield became obscured by it. John Garfield (March 4, 1913 – May 21, 1952) was born as Jacob Julius Garfinkle in a small apartment on Rivington Street in Manhattan's Lower East Side, to David and Hannah Garfinkle, Russian Jewish immigrants. Garfield's father, a clothes presser and part time cantor, struggled to make a living and to provide even marginal comfort for his family. His widowed father remarried and moved to the West Bronx where Garfield joined a series of gangs.

John Garfield (March 4, 1913 – May 21, 1952) was born as Jacob Julius Garfinkle in a small apartment on Rivington Street in Manhattan's Lower East Side, to David and Hannah Garfinkle, Russian Jewish immigrants. Garfield's father, a clothes presser and part time cantor, struggled to make a living and to provide even marginal comfort for his family. His widowed father remarried and moved to the West Bronx where Garfield joined a series of gangs. Much later he would recall: "Every street had its own gang. That's the way it was in poor sections... the old safety in numbers." He soon become gang leader. At this time people started to notice his ability to mimic well-known performers, both bodily and facially. He also began to hang out and eventually spar at a boxing gym on Jerome Avenue. It was under the guidance of the school's principal Angelo Patri that he was introduced to acting.

Much later he would recall: "Every street had its own gang. That's the way it was in poor sections... the old safety in numbers." He soon become gang leader. At this time people started to notice his ability to mimic well-known performers, both bodily and facially. He also began to hang out and eventually spar at a boxing gym on Jerome Avenue. It was under the guidance of the school's principal Angelo Patri that he was introduced to acting. He began to take acting lessons at a drama school part of The Heckscher Foundation and was recommended to attend the American Laboratory Theater. Funded by the Theatre Guild, "The Lab" had contracted with Richard Boleslavski to stage its experimental productions and with Russian actress and expatriate Maria Ouspenskaya to supervise classes.

He began to take acting lessons at a drama school part of The Heckscher Foundation and was recommended to attend the American Laboratory Theater. Funded by the Theatre Guild, "The Lab" had contracted with Richard Boleslavski to stage its experimental productions and with Russian actress and expatriate Maria Ouspenskaya to supervise classes. Garfield took morning classes and began volunteering time at the Lab after hours, auditing rehearsals, building and painting scenery, and doing crew work. Among the people becoming disenchanted with the Guild and turning to the Lab for a more radical, challenging environment were Stella Adler, Lee Strasberg, Franchot Tone, Cheryl Crawford and Harold Clurman.

Garfield took morning classes and began volunteering time at the Lab after hours, auditing rehearsals, building and painting scenery, and doing crew work. Among the people becoming disenchanted with the Guild and turning to the Lab for a more radical, challenging environment were Stella Adler, Lee Strasberg, Franchot Tone, Cheryl Crawford and Harold Clurman. Garfield contracted typhoid fever (which would cause irreparable heart damage for life) from taking a drink of water from a contaminated well in Nebraska. He welcomed 1931 in a hospital bed. After a stint with Eva Le Gallienne's Civic Repertory Theater and a short period of vagrancy involving hitchhiking, freight hopping, picking fruit, logging in the Pacific Northwest (Preston Sturges conceived the film 'Sullivan's Travels' after Garfield's hobo adventures) Garfield made his Broadway debut in 1932, in a play called 'Lost Boy'.

Garfield contracted typhoid fever (which would cause irreparable heart damage for life) from taking a drink of water from a contaminated well in Nebraska. He welcomed 1931 in a hospital bed. After a stint with Eva Le Gallienne's Civic Repertory Theater and a short period of vagrancy involving hitchhiking, freight hopping, picking fruit, logging in the Pacific Northwest (Preston Sturges conceived the film 'Sullivan's Travels' after Garfield's hobo adventures) Garfield made his Broadway debut in 1932, in a play called 'Lost Boy'. John Garfield and Priscilla Lane in "Four Daughters" (1938) directed by Michael Curtiz

John Garfield and Priscilla Lane in "Four Daughters" (1938) directed by Michael CurtizHis first film, 'Four Daughters' (1938) by Michael Curtiz, was a surprise hit and he received an Oscar nomination.

Priscilla Lane and John Garfield in "Dust Be My Destiny" (1939) directed by Lewis Seiler

Priscilla Lane and John Garfield in "Dust Be My Destiny" (1939) directed by Lewis Seiler Robert Nott in his biography of John Garfield, 'He Ran All the Way', describes an actor struggling to find projects worthy of his talent. This led to Garfield forming his own production company to try to develop challenging projects, which he did later in his career.

Robert Nott in his biography of John Garfield, 'He Ran All the Way', describes an actor struggling to find projects worthy of his talent. This led to Garfield forming his own production company to try to develop challenging projects, which he did later in his career. Some of the films he appeared in included 'The Sea Wolf', 'Tortilla Flat', 'Destination Tokyo', 'Humoresque', 'Pride of the Marines', and 'Gentleman's Agreement'.

Some of the films he appeared in included 'The Sea Wolf', 'Tortilla Flat', 'Destination Tokyo', 'Humoresque', 'Pride of the Marines', and 'Gentleman's Agreement'. According to Nott, author of the excellent biography 'He Ran All the Way', Garfield’s first movie role, as Mickey Borden in 'Four Daughters', gave him the chance to basically sculpt the mold for the sensitive tough-guy, the anti-hero, the outcast on screen.

According to Nott, author of the excellent biography 'He Ran All the Way', Garfield’s first movie role, as Mickey Borden in 'Four Daughters', gave him the chance to basically sculpt the mold for the sensitive tough-guy, the anti-hero, the outcast on screen. Not surprisingly Warner Bros. - which prided itself on its line-up of tough-guy actors including James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, George Raft, and Humphrey Bogart – saw how audiences responded to Garfield’s sensitive, doomed pianist, and simply transplanted that character (and the actor) into gangster stories, prison dramas, and heel-on-the-lam pictures.

Not surprisingly Warner Bros. - which prided itself on its line-up of tough-guy actors including James Cagney, Edward G. Robinson, George Raft, and Humphrey Bogart – saw how audiences responded to Garfield’s sensitive, doomed pianist, and simply transplanted that character (and the actor) into gangster stories, prison dramas, and heel-on-the-lam pictures. "A composite movie image of John Garfield, the most modern of 1940's Hollywood actors, finds him hurrying furtively through a shabby Manhattan neighborhood late at night to keep an assignation with some shady characters in a desolate Edward Hopper cafe. Stopping for a moment, he bends under a street lamp, cupping his hands to light a cigarette, his hat tilted down over one eyebrow, the collar of his overcoat turned up against the late-November chill".

"A composite movie image of John Garfield, the most modern of 1940's Hollywood actors, finds him hurrying furtively through a shabby Manhattan neighborhood late at night to keep an assignation with some shady characters in a desolate Edward Hopper cafe. Stopping for a moment, he bends under a street lamp, cupping his hands to light a cigarette, his hat tilted down over one eyebrow, the collar of his overcoat turned up against the late-November chill". John Garfield, frustrated that he could not enlist because of his heart condition, founded the Hollywood Canteen with Bette Davis. It was a club that offered food and entertainment to American servicemen. For five years he entertained the troops all over the world.

John Garfield, frustrated that he could not enlist because of his heart condition, founded the Hollywood Canteen with Bette Davis. It was a club that offered food and entertainment to American servicemen. For five years he entertained the troops all over the world. According to Robert Nott, "Garfield has to be considered as one of Warner Bros. top five stars from 1939-1946. But he was never the top star. Cagney, Robinson, and even George Raft dominated the period from 1939-1942; Bogart broke through as a star in the 1941/1942 period, eclipsing Garfield in the early 1940's.

According to Robert Nott, "Garfield has to be considered as one of Warner Bros. top five stars from 1939-1946. But he was never the top star. Cagney, Robinson, and even George Raft dominated the period from 1939-1942; Bogart broke through as a star in the 1941/1942 period, eclipsing Garfield in the early 1940's. Late in his career, Garfield starred in a number of film noirs that have stood the test of time. "Garfield’s position as a film noir icon is somewhat assured, and even younger people who follow the noir movement know his work. Today’s critics and historians are, in fact, more likely to pay attention to the post-war, non-Warner Bros. noirs that Garfield acted in during the late 1940s," said Nott.

Late in his career, Garfield starred in a number of film noirs that have stood the test of time. "Garfield’s position as a film noir icon is somewhat assured, and even younger people who follow the noir movement know his work. Today’s critics and historians are, in fact, more likely to pay attention to the post-war, non-Warner Bros. noirs that Garfield acted in during the late 1940s," said Nott. John Garfield under examination before the House Committe on Unamerican Activities (April 23, 1951)

John Garfield under examination before the House Committe on Unamerican Activities (April 23, 1951) John Garfield had been a supporter of left-wing causes, but not a communist. According to author Jake Hinkson in an article he wrote for the Noir City Sentinel in 2009: "These people were all small fish, though. What the Committee really wanted was someone big. That meant a bona fide movie star, and almost from the beginning they had their eye on John Garfield. He was dragged before the Committee where he denied knowing anything about Communism. He denied having ever met a single Communist. These were blatant lies (his wife Robbie had been a party member), but Garfield had never been a party member, and he had no desire to put the finger on any of his friends just to save his career".

John Garfield had been a supporter of left-wing causes, but not a communist. According to author Jake Hinkson in an article he wrote for the Noir City Sentinel in 2009: "These people were all small fish, though. What the Committee really wanted was someone big. That meant a bona fide movie star, and almost from the beginning they had their eye on John Garfield. He was dragged before the Committee where he denied knowing anything about Communism. He denied having ever met a single Communist. These were blatant lies (his wife Robbie had been a party member), but Garfield had never been a party member, and he had no desire to put the finger on any of his friends just to save his career". "The Committee asked him about John Berry and Hugo Butler, both of whom had fled the country. Garfield said nothing. They asked him who wrote 'He Ran All The Way', and he didn’t mention Dalton Trumbo, (one of the writers). When Garfield refused to turn rat, HUAC gave his testimony to the FBI and asked them to build a perjury case. The studios stopped hiring him.

"The Committee asked him about John Berry and Hugo Butler, both of whom had fled the country. Garfield said nothing. They asked him who wrote 'He Ran All The Way', and he didn’t mention Dalton Trumbo, (one of the writers). When Garfield refused to turn rat, HUAC gave his testimony to the FBI and asked them to build a perjury case. The studios stopped hiring him. One of the biggest movie stars of the 1940's —a man with two Oscar nominations and millions of fans was done in Hollywood. The FBI started tailing him, eventually compiling a thousand-page file on the comings and goings of an out-of-work actor. Panicked, Garfield wrote an article for Look magazine called “I Was A Sucker For A Left Hook” in which he denounced Communism and said he’d been duped into supporting various leftist causes. The magazine refused to publish it.

One of the biggest movie stars of the 1940's —a man with two Oscar nominations and millions of fans was done in Hollywood. The FBI started tailing him, eventually compiling a thousand-page file on the comings and goings of an out-of-work actor. Panicked, Garfield wrote an article for Look magazine called “I Was A Sucker For A Left Hook” in which he denounced Communism and said he’d been duped into supporting various leftist causes. The magazine refused to publish it. ‘I’ll act anywhere,’ he told a columnist in late 1951. But his career was over. In May of 1952, he died suddenly of a heart attack.” Director Berry, a native New Yorker, who left the country because of the blacklist and directed films in France for decades, said the pressure to cooperate with the Committee was very powerful.

‘I’ll act anywhere,’ he told a columnist in late 1951. But his career was over. In May of 1952, he died suddenly of a heart attack.” Director Berry, a native New Yorker, who left the country because of the blacklist and directed films in France for decades, said the pressure to cooperate with the Committee was very powerful. “The tension to play ball must have crossed his mind. This may sound romantic but I think what happened was, faced with this option, Julius Garfinkle of the Bronx said to the John Garfield of Hollywood, ‘You can’t do this to me.’ And John Garfield packed his bags and died. The only way to clear himself was to rat and he couldn’t do that.” Source: atyourlibrary.org

“The tension to play ball must have crossed his mind. This may sound romantic but I think what happened was, faced with this option, Julius Garfinkle of the Bronx said to the John Garfield of Hollywood, ‘You can’t do this to me.’ And John Garfield packed his bags and died. The only way to clear himself was to rat and he couldn’t do that.” Source: atyourlibrary.org "He never lived long enough to become an icon like Humphrey Bogart", said David Heeley, one of the producers of "The John Garfield Story" a documentary that had its premiere on Turner Classic Movies. "He didn't know what happened to him in the end," Mr. Heeley said. "He didn't understand why they were hounding him. In the end he was scared."

"He never lived long enough to become an icon like Humphrey Bogart", said David Heeley, one of the producers of "The John Garfield Story" a documentary that had its premiere on Turner Classic Movies. "He didn't know what happened to him in the end," Mr. Heeley said. "He didn't understand why they were hounding him. In the end he was scared." His daughter, Julie Garfield, an acting teacher in New York, put it another way. "He was horribly neglected, forgotten, pushed aside," she said. "It was almost as if Hollywood was so ashamed of what was done to him that they almost made him disappear."

His daughter, Julie Garfield, an acting teacher in New York, put it another way. "He was horribly neglected, forgotten, pushed aside," she said. "It was almost as if Hollywood was so ashamed of what was done to him that they almost made him disappear." Garfield is most remembered for his role opposite Lana Turner, in Tay Garnett's sexy drama "The Postman Always Rings Twice" (1946), based on James M. Cain's novel. His other films included "Humoresque" (1947), with Joan Crawford;

Garfield is most remembered for his role opposite Lana Turner, in Tay Garnett's sexy drama "The Postman Always Rings Twice" (1946), based on James M. Cain's novel. His other films included "Humoresque" (1947), with Joan Crawford; Robert Rossen's classic "Body and Soul" (1947), in which he works his way up from poverty to become a champion boxer at great personal cost; and Abraham Polonsky's "Force of Evil" (1948), in which Garfield was acclaimed for his role as a greedy lawyer for racketeers.

Robert Rossen's classic "Body and Soul" (1947), in which he works his way up from poverty to become a champion boxer at great personal cost; and Abraham Polonsky's "Force of Evil" (1948), in which Garfield was acclaimed for his role as a greedy lawyer for racketeers. He also played the Jewish friend of Gregory Peck's character in Elia Kazan's "Gentlemen's Agreement" (1947), about anti-Semitism. Garfield was nominated twice for Oscars, as a supporting actor for his first film, "Four Daughters" (1938), and as best actor for "Body and Soul" (1947).

He also played the Jewish friend of Gregory Peck's character in Elia Kazan's "Gentlemen's Agreement" (1947), about anti-Semitism. Garfield was nominated twice for Oscars, as a supporting actor for his first film, "Four Daughters" (1938), and as best actor for "Body and Soul" (1947). Just before his 22nd birthday in 1935, Garfield had married his childhood sweetheart from the Bronx, Roberta Seidman. They had three children: Katherine (1938–1945), who died of an allergic reaction on March 18, 1945, David (1943–1994), and Julie (born 1946), the latter two later becoming actors themselves. Source: themave.com

Just before his 22nd birthday in 1935, Garfield had married his childhood sweetheart from the Bronx, Roberta Seidman. They had three children: Katherine (1938–1945), who died of an allergic reaction on March 18, 1945, David (1943–1994), and Julie (born 1946), the latter two later becoming actors themselves. Source: themave.com David Garfinkle (John Garfield's father) was indifferent to his son's enormous success; reportedly he never saw one of his son's films; that aspect of their troubled relationship must have caused Garfield considerable pain.

David Garfinkle (John Garfield's father) was indifferent to his son's enormous success; reportedly he never saw one of his son's films; that aspect of their troubled relationship must have caused Garfield considerable pain. Garfield got along well with Ann Sheridan during the filming of 'They Made Me a Criminal' (1939), who was cast as the secondary female lead. An early scene called for Sheridan to passionately kiss Julie on a couch. Director Busby Berkeley told Sheridan "Hold it until I say cut".

Garfield got along well with Ann Sheridan during the filming of 'They Made Me a Criminal' (1939), who was cast as the secondary female lead. An early scene called for Sheridan to passionately kiss Julie on a couch. Director Busby Berkeley told Sheridan "Hold it until I say cut". Sheridan did as told, Berkeley never yelled cut. Garfield tried to squirm away but Sheridan held fast, knocking him off the couch and onto the floor. The cast and crew loved it. Garfield was the perfect fall guy for such occasions; Berkeley and Sheridan had prearranged the entire bit to make him uncomfortable. Oddly enough, whatever his offscreen reputation as a lover, Garfield disliked onscreen lovemaking.

Sheridan did as told, Berkeley never yelled cut. Garfield tried to squirm away but Sheridan held fast, knocking him off the couch and onto the floor. The cast and crew loved it. Garfield was the perfect fall guy for such occasions; Berkeley and Sheridan had prearranged the entire bit to make him uncomfortable. Oddly enough, whatever his offscreen reputation as a lover, Garfield disliked onscreen lovemaking. "He was shy, vibrant and intelligent. And so ahead of his time. He had terrific magnetism", said John Garfield's 'The Postman Always Rings Twice' co-star Lana Turner. "The only co-star I know that he had an affair with, actually, was Lana Turner", Vincent Sherman (director of 'The Damned Don't Cry', 'The Hasty Heart' etc.) remembered.

"He was shy, vibrant and intelligent. And so ahead of his time. He had terrific magnetism", said John Garfield's 'The Postman Always Rings Twice' co-star Lana Turner. "The only co-star I know that he had an affair with, actually, was Lana Turner", Vincent Sherman (director of 'The Damned Don't Cry', 'The Hasty Heart' etc.) remembered. Unlike other noir actors, Garfield, as a film producer, helped create his own noir world. It was as if he realized he belonged in that strange netherworld of cinema. Once in, it's nearly impossible to get out.

Unlike other noir actors, Garfield, as a film producer, helped create his own noir world. It was as if he realized he belonged in that strange netherworld of cinema. Once in, it's nearly impossible to get out. On Broadway, Garfield and Bob Roberts saw actress Beatrice Pearson in the comedy hit 'The Voice of the Turtle' and Roberts put her under contract.

On Broadway, Garfield and Bob Roberts saw actress Beatrice Pearson in the comedy hit 'The Voice of the Turtle' and Roberts put her under contract. Pearson was more or less forced upon screenwriter Polonsky as the love interest in 'Force of Evil'. Pearson is one actress who does not seem to sexually connect with John Garfield on screen.

Pearson was more or less forced upon screenwriter Polonsky as the love interest in 'Force of Evil'. Pearson is one actress who does not seem to sexually connect with John Garfield on screen. If Garfield was hoping to make a pass at her off screen, he was to be disappointed: According to both Abraham Polonsky and Marie Windsor, Pearson was a lesbian. Like 'Body and Soul', 'Force of Evil' is concerned with corruption. In 'Body and Soul' this corrupt world doesn't collapse, only Charley Davis does.

If Garfield was hoping to make a pass at her off screen, he was to be disappointed: According to both Abraham Polonsky and Marie Windsor, Pearson was a lesbian. Like 'Body and Soul', 'Force of Evil' is concerned with corruption. In 'Body and Soul' this corrupt world doesn't collapse, only Charley Davis does. In 'Force of Evil', just about everybody goes down with the ship. Martin Scorsese loves 'Force of Evil' which influenced his own work. "'Force of Evil' never died", Polonsky said in the early 1990's, "and it's a better picture than 'Body and Soul'".

In 'Force of Evil', just about everybody goes down with the ship. Martin Scorsese loves 'Force of Evil' which influenced his own work. "'Force of Evil' never died", Polonsky said in the early 1990's, "and it's a better picture than 'Body and Soul'". Before filming 'The Breaking Point' (1950) was completed, Garfield called Phyllis Thaxter up one evening and asked her to have dinner with him. She declined. With Thaxter he had been gentle, funny and flirtatious both on and off the set.

Before filming 'The Breaking Point' (1950) was completed, Garfield called Phyllis Thaxter up one evening and asked her to have dinner with him. She declined. With Thaxter he had been gentle, funny and flirtatious both on and off the set. With Patricia Neal, he was brusque, rough and sarcastic. "He was kind of macho", Neal said years later with a laugh. "Like he had to play the part off the screen as well. It kind of turned me off".

With Patricia Neal, he was brusque, rough and sarcastic. "He was kind of macho", Neal said years later with a laugh. "Like he had to play the part off the screen as well. It kind of turned me off".Tuesday, August 27, 1940

"Called up Julie (now John) Garfield. Over he came in a hurry, thinking that he should not be feeling juniorish to me and yet feeling that way. We talked a long time, he mostly uneasy because of a waning connection with his wife and a prurience that makes him, so he said, want to sleep with every woman he looks at. He said that it didn’t matter here what you did or who you were – it was only a matter of different brands of canned tuna fish, screen actors, films and all".

Thursday, October 3, 1940

"I left Julie with a motto, he having brought up the matter first: “A slack string has no tone.” Anyone with any character is always worried in Hollywood by the slack feeling of the self".

-extracts from "The Time Is Ripe: The 1940 Journal of Clifford Odets" -With an Introduction by William Gibson (1989)

John Garfield was without doubt the only major movie star of the period to be blacklisted. And the blacklist may have played a part in his current lack of standing as a Hollywood icon.

John Garfield was without doubt the only major movie star of the period to be blacklisted. And the blacklist may have played a part in his current lack of standing as a Hollywood icon. "John Garfield testified under oath in 1951 that he had never been a member of the Communist Party. The Committee did not believe him and asked the FBI to see if there were grounds for perjury; from that moment on he could not get work in Hollywood. Kazan testified before the Committee in early 1952, admitting his own associations with the Communist Party but refusing to name anyone else. Pressured to cooperate more fully if he wanted to avoid the blacklist, Kazan named names in a closed executive hearing in April.

"John Garfield testified under oath in 1951 that he had never been a member of the Communist Party. The Committee did not believe him and asked the FBI to see if there were grounds for perjury; from that moment on he could not get work in Hollywood. Kazan testified before the Committee in early 1952, admitting his own associations with the Communist Party but refusing to name anyone else. Pressured to cooperate more fully if he wanted to avoid the blacklist, Kazan named names in a closed executive hearing in April. Then on May 18 Garfield finished a long confession and began walking the streets of New York-- in despair apparently, according to friends interviewed after the fact.

Then on May 18 Garfield finished a long confession and began walking the streets of New York-- in despair apparently, according to friends interviewed after the fact. Clifford Odets appeared before the Committee on May 19 and 20, having already taken Kazan’s testimony to heart, and while he did not name Garfield, he did name another Group Theater friend, recently blacklisted and recently dead (prematurely) of an apparent heart attack at age 48, J. Edward Bromberg. Because Odets’s testimony was broadcast live on the radio, Garfield would have heard the voice of his old friend coming from open apartment house windows as he walked about the city that day.

Clifford Odets appeared before the Committee on May 19 and 20, having already taken Kazan’s testimony to heart, and while he did not name Garfield, he did name another Group Theater friend, recently blacklisted and recently dead (prematurely) of an apparent heart attack at age 48, J. Edward Bromberg. Because Odets’s testimony was broadcast live on the radio, Garfield would have heard the voice of his old friend coming from open apartment house windows as he walked about the city that day. It must have been stressful, since sometime during the early morning hours of May 21, he died in the New York apartment of Iris Whitney, a woman friend. Garfield was only 39, the victim of an apparent heart attack. Two days later The New York Times reported that over 10,000 people crowded his funeral, and printed a letter from Odets who proclaimed his undying love for his friend, Julie.

It must have been stressful, since sometime during the early morning hours of May 21, he died in the New York apartment of Iris Whitney, a woman friend. Garfield was only 39, the victim of an apparent heart attack. Two days later The New York Times reported that over 10,000 people crowded his funeral, and printed a letter from Odets who proclaimed his undying love for his friend, Julie. Director Elia Kazan filming "A Face in the Crowd" with Patricia Neal and Lee Remick (1956)

Director Elia Kazan filming "A Face in the Crowd" with Patricia Neal and Lee Remick (1956) Elia Kazan, who cooperated with the committee after some initial misgivings, was the only one to go on to a gloriously successful Hollywood career. Kazan’s memoirs, published in 1988, are long, ungainly, boastful (about having an sexual affair with Marilyn Monroe), crude, and unrepentant. A decade later Kazan received an honorary Academy Award, although not everyone in the audience was willing to applaud and he remained despised by those of his old friends on the left who were still alive. It is not possible to understand the debate over mass culture in the 1950s without knowing this history as well". Source: cla.calpoly.edu

Elia Kazan, who cooperated with the committee after some initial misgivings, was the only one to go on to a gloriously successful Hollywood career. Kazan’s memoirs, published in 1988, are long, ungainly, boastful (about having an sexual affair with Marilyn Monroe), crude, and unrepentant. A decade later Kazan received an honorary Academy Award, although not everyone in the audience was willing to applaud and he remained despised by those of his old friends on the left who were still alive. It is not possible to understand the debate over mass culture in the 1950s without knowing this history as well". Source: cla.calpoly.edu

No comments :

Post a Comment