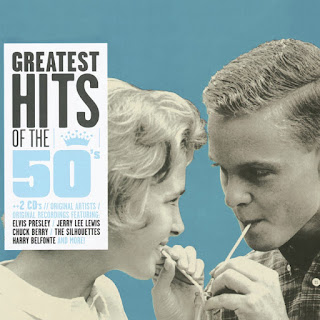

The United States was the most influential economic power in the world after World War II under the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower. Inflation was moderate during the decade of the 1950s. The first few months had a deflationary hangover from the 1940s but the first full year ended with annual inflation rates ranging from 8% to 9%. By 1952 inflation subsided. 1954 and 1955 flirted with deflation again but the remainder of the decade had moderate inflation ranging from 1% to 3.7%. The average annual inflation for the entire decade was only 2.04%. The fifties has been heralded as the decade of a great social comfort and widespread cultural consensus. The fifties was also the decade when rock and roll officially broke out. The interaction of country music with jazz and R&B was especially important in the creation of rock and roll, but though western swing influence—country music’s string-powered response to big-band jazz—has been recently researched, the “hillbilly boogie,” which bridged the gap between western swing and the rockabilly genre, has been virtually ignored.

Hollywood musicals and animated cartoons helped popularize swing, and western films created a national audience for country music. “Blueberry Hill” became a rock classic at the hands of Fats Domino in 1956, but the song, which had been a No. 1 pop hit for Glenn Miller in 1940, was also sung by Gene Autry in 1941, and recorded in 1949 by Louis Armstrong. For the most part, the blues found its way into rock music through jazz, which had long incorporated blues in the early 1920s. With rare exceptions, the Delta blues had little impact on rock ’n’ roll before the British Invasion of the mid-1960s regarded it as influential. During the swing era, big bands such as Count Basie’s, Benny Goodman’s, and Tommy Dorsey’s had picked up the boogie-woogie sound, while blues and country music took on a jazzy feel. The roots of rock run through mainstream pop as well, from Irving Berlin’s vaudeville songs to the Andrews Sisters’ harmonized boogie-woogies, and the R&B-flavored crooning of Frankie Laine and Johnnie Ray. The nascent sound of rock ’n’ roll could be heard as early as the 1920s in a number of piano boogies, and jazz-band arrangements.

Before Elvis Presley or Bill Haley had a hit, the pop singer Kay Starr made the Top 20 with her cover version of the Clovers’ 1951 rhythm-and-blues chart-topper “Fool, Fool, Fool.” Before Little Richard turned it into a rock ’n’ roll anthem in 1957, “Keep A Knockin’” was recorded by James Wiggins and by Bert Mays in 1928, by Lil Johnson in 1935, by Milton Brown in 1936, by Louis Jordan and by Jimmy Dorsey in 1939, and by Jimmy Yancey in 1950, among others. Most official rock ’n’ roll timelines begin with the late 1940s or early 1950s. Only a few historians, such as Ed Ward (The History of Rock & Roll: 1920-1963), Geoffrey Stokes (Star-Making Machinery: Inside the Business of Rock and Roll), or Robert Palmer (Rock & Roll: An Unruly History), dare to trace the rock and roll origins as early as the 1930s. Perhaps the best explanation of the origins of rock is still to be found in Charlie Gillett’s The Sound of the City (first published in 1970), one of the only books to recognize the link between big-band swing and rock ’n’ roll. Another writer who has traced some of the various musical strains that found their way into rock ’n’ roll is Nick Tosches (Unsung Heroes of Rock ’n’ Roll: The Birth Of Rock In The Wild Years Before Elvis).

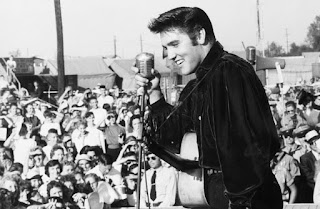

Both Sam Phillips and Marion Keisker heatedly denied Phillips' alleged remark as Albert Goldman quoted it in his 1981 biography of Elvis Presley: “If I could find a white boy who could sing like a nigger, I could make a million dollars.” In 1957, Presley recorded “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin” as the flip side of “All Shook Up,” with the Jordanaires adding vocal harmonies. Listening to these earliest Elvis recordings today, it is nearly impossible to understand the apocryphal Sam Phillips quote: the eighteen-year-old Presley does not sound black at all. Peter Guralnick (Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley) compares the voice of Elvis on his early demos to “a sentimental Irish tenor,” adding that “there could have been nothing less overtly African-American-sounding than this particular acetate or this particular song.” Presley evidently aspired to be a country-pop crooner, and though he earned the title King of Rock ’n’ Roll with up-tempo rockers such as “Hound Dog” and “All Shook Up,” he continued to sing and record ballads throughout his career. Published reports that Presley frequented blues clubs on Beale Street in Memphis while still in high school were also debunked by Peter Guralnick.

Presley’s early exposure to live music came mainly through shows by white gospel quartets such as the Blackwood Brothers and the Statesmen. Radio was Presley’s primary source of musical inspiration, but though he surely tuned in to the pioneering Memphis rhythm-and-blues station WDIA, his repertoire was largely drawn from pop singers such as Teresa Brewer, Jo Stafford, Bing Crosby, Dean Martin, Eddie Fisher, and Perry Como, as well as country singers such as Hank Williams, Eddie Arnold, and Hank Snow. John Lennon, in his final 1980 interview, told David Sheff that “Rock Around the Clock” had inspired him to pursue a musical career. “I really enjoyed Bill Haley, but I wasn’t overwhelmed by him,” Lennon added. “It wasn’t until ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ that I really got into it.” It was Lennon who is said to have stated, “Before Elvis, there was nothing,” although this widely circulated quotation appears to be apocryphal. By the early 1950s, hillbilly boogies were no longer novel. Boogie-woogie fever had swept America in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Western swing, country music’s fiddle-driven answer to big-band jazz, followed suit. The roots of rock are audible on “Boogie Woogie,” which Count Basie recorded with a small combo in 1936 and with his big band in 1937 (both versions featuring singer Jimmy Rushing), and which Tommy Dorsey recorded as an instrumental in 1938. Boogie-woogie fever peaked with “Beat Me Daddy,” a big hit for the Andrews Sisters in 1940, the same year that Frank Sinatra made his first records with Tommy Dorsey.

Hollywood musicals and animated cartoons helped popularize swing, and western films created a national audience for country music. “Blueberry Hill” became a rock classic at the hands of Fats Domino in 1956, but the song, which had been a No. 1 pop hit for Glenn Miller in 1940, was also sung by Gene Autry in 1941, and recorded in 1949 by Louis Armstrong. For the most part, the blues found its way into rock music through jazz, which had long incorporated blues in the early 1920s. With rare exceptions, the Delta blues had little impact on rock ’n’ roll before the British Invasion of the mid-1960s regarded it as influential. During the swing era, big bands such as Count Basie’s, Benny Goodman’s, and Tommy Dorsey’s had picked up the boogie-woogie sound, while blues and country music took on a jazzy feel. The roots of rock run through mainstream pop as well, from Irving Berlin’s vaudeville songs to the Andrews Sisters’ harmonized boogie-woogies, and the R&B-flavored crooning of Frankie Laine and Johnnie Ray. The nascent sound of rock ’n’ roll could be heard as early as the 1920s in a number of piano boogies, and jazz-band arrangements.

Before Elvis Presley or Bill Haley had a hit, the pop singer Kay Starr made the Top 20 with her cover version of the Clovers’ 1951 rhythm-and-blues chart-topper “Fool, Fool, Fool.” Before Little Richard turned it into a rock ’n’ roll anthem in 1957, “Keep A Knockin’” was recorded by James Wiggins and by Bert Mays in 1928, by Lil Johnson in 1935, by Milton Brown in 1936, by Louis Jordan and by Jimmy Dorsey in 1939, and by Jimmy Yancey in 1950, among others. Most official rock ’n’ roll timelines begin with the late 1940s or early 1950s. Only a few historians, such as Ed Ward (The History of Rock & Roll: 1920-1963), Geoffrey Stokes (Star-Making Machinery: Inside the Business of Rock and Roll), or Robert Palmer (Rock & Roll: An Unruly History), dare to trace the rock and roll origins as early as the 1930s. Perhaps the best explanation of the origins of rock is still to be found in Charlie Gillett’s The Sound of the City (first published in 1970), one of the only books to recognize the link between big-band swing and rock ’n’ roll. Another writer who has traced some of the various musical strains that found their way into rock ’n’ roll is Nick Tosches (Unsung Heroes of Rock ’n’ Roll: The Birth Of Rock In The Wild Years Before Elvis).

Both Sam Phillips and Marion Keisker heatedly denied Phillips' alleged remark as Albert Goldman quoted it in his 1981 biography of Elvis Presley: “If I could find a white boy who could sing like a nigger, I could make a million dollars.” In 1957, Presley recorded “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin” as the flip side of “All Shook Up,” with the Jordanaires adding vocal harmonies. Listening to these earliest Elvis recordings today, it is nearly impossible to understand the apocryphal Sam Phillips quote: the eighteen-year-old Presley does not sound black at all. Peter Guralnick (Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley) compares the voice of Elvis on his early demos to “a sentimental Irish tenor,” adding that “there could have been nothing less overtly African-American-sounding than this particular acetate or this particular song.” Presley evidently aspired to be a country-pop crooner, and though he earned the title King of Rock ’n’ Roll with up-tempo rockers such as “Hound Dog” and “All Shook Up,” he continued to sing and record ballads throughout his career. Published reports that Presley frequented blues clubs on Beale Street in Memphis while still in high school were also debunked by Peter Guralnick.

Presley’s early exposure to live music came mainly through shows by white gospel quartets such as the Blackwood Brothers and the Statesmen. Radio was Presley’s primary source of musical inspiration, but though he surely tuned in to the pioneering Memphis rhythm-and-blues station WDIA, his repertoire was largely drawn from pop singers such as Teresa Brewer, Jo Stafford, Bing Crosby, Dean Martin, Eddie Fisher, and Perry Como, as well as country singers such as Hank Williams, Eddie Arnold, and Hank Snow. John Lennon, in his final 1980 interview, told David Sheff that “Rock Around the Clock” had inspired him to pursue a musical career. “I really enjoyed Bill Haley, but I wasn’t overwhelmed by him,” Lennon added. “It wasn’t until ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ that I really got into it.” It was Lennon who is said to have stated, “Before Elvis, there was nothing,” although this widely circulated quotation appears to be apocryphal. By the early 1950s, hillbilly boogies were no longer novel. Boogie-woogie fever had swept America in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Western swing, country music’s fiddle-driven answer to big-band jazz, followed suit. The roots of rock are audible on “Boogie Woogie,” which Count Basie recorded with a small combo in 1936 and with his big band in 1937 (both versions featuring singer Jimmy Rushing), and which Tommy Dorsey recorded as an instrumental in 1938. Boogie-woogie fever peaked with “Beat Me Daddy,” a big hit for the Andrews Sisters in 1940, the same year that Frank Sinatra made his first records with Tommy Dorsey.

Duke Ellington took a more inclusive view in an article for Music Journal in 1962. “Rock ’n’ Roll is the most raucous form of jazz, beyond a doubt,” he wrote. “It maintains a link with the folk origins, and I believe that no other form of jazz has ever been accepted so enthusiastically by so many.” “Lovesick Blues,” a Tin Pan Alley song written by Irving Mills and Cliff Friend, was first recorded in 1922 by the vaudeville singer Elsie Clark. In 1928, Emmett Miller rerecorded “Lovesick Blues” in New York with a group of jazz musicians including trombonist Tommy Dorsey, saxophonist Jimmy Dorsey, and guitarist Eddie Lang. Rex Griffin’s 1939 cover of Miller’s “Lovesick Blues” is the basis for Hank Williams’s 1949 version, the biggest hit of Williams’s career. According to Peter Guralnick, Elvis Presley “sang quite a few of Kay Starr’s songs” while still in high school, but these were probably ballads. “Fool, Fool, Fool”/“Kay’s Lament” has been overlooked by compilers of the first rock ’n’ roll records, and though the Oklahoma-born Starr was a “white” southerner who scored pop hits mixing rhythm-and-blues in an authentic style before Bill Haley, she has so far escaped consideration as the first rock ’n’ roll singer (as has Anita O’Day). One of Decca’s first post-band recordings was of Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters’ version of “Pistol Packin’ Mama,” a country, pop, and R&B hit. “Pistol Packin’ Mama” was covered by artists ranging from the Pied Pipers (a white vocal group featuring Jo Stafford) to the Hurricanes (a black doo-wop group) to Gene Vincent, whose rockabilly rendition, recorded in London, was arranged by Eddie Cochran.

Although Elvis Presley adapted some of his music directly from rhythm-and-blues and claimed that genre as the source of his style, it’s clear from his recording of “Milkcow Blues Boogie” that he was acquainted with western swing, and it’s hardly credible that he was less than familiar with the hillbilly boogie. Bill Haley’s roots in western swing and hillbilly boogie are well documented, and the melody of “Rock Around the Clock,” originally published by the African American bandleader Richard M. Jones, can be heard in a number of 1940s country songs. By the early 1950s, if not sooner, country artists were recording in an idiom recognizable as rockabilly or rock ’n’ roll, terms that would not be used to characterize the genre until a few years later. Swept up in the wave of enthusiasm that accompanied rock ’n’ roll’s breakthrough into the popular mainstream, Haley and Presley were hailed as musical pioneers, but they just were following a well-worn stylistic path. “Rock Around the Clock” was not the first rock and roll song, despite its shuffling rhythm, boogie-ish bass line, and twelve-bar verse-and-refrain structure. Although many 1950s rock songs feature one or more of these characteristics, many do not. Others, such as “Blue Suede Shoes” or “Jailhouse Rock,” have a sixteen-bar verse-and-refrain structure; “Great Balls of Fire” follows the thirty-two bar AABA pattern typical of ballads, complete with bridge.

Upon its emergence, rock ’n’ roll encountered a firestorm of criticism. “From 1958 to 1960 rock and roll lost much of its early drive and impetus, due largely to anti-rock pressures. From 1960 to 1962 rock and roll was toned down,” write Linda Martin and Kerry Segrave in Anti-Rock: Opposition to Rock and Roll. The songwriters headquartered in Manhattan’s Brill Building put their own distinctive stamp, a kind of pop-rock update on Tin Pan Alley, while the surf music of southern California brought guitar instrumentals to the forefront. The demise of rock ’n’ roll has been proclaimed at least since Don McLean’s 1971 hit “American Pie” lamented the passing of Buddy Holly on “the day the music died.” Nevertheless, rock lives on, however feebly, having shown relatively little creative spark since the grunge era. The remaining rock scene splintered into subgenres: power pop, psychobilly, post-punk, grunge, lo-fi, and Americana. Paralleling the development of jazz, rock music has grown so distant from its original sound that modern rock hardly seems to belong to the same genre as vintage rock ’n’ roll. Only the backbeat and amplified guitar-bass-and-drums instrumentation have endured. Rock ’n’ roll showed its greatest verve in the mid-1950s, being revived several times, spiking during the folk-rock and psychedelic rock of the 60s, the 70s glam/punk, the 80s new wave and the 90s grunge/avant-garde. What genuine inventiveness persists is mostly relegated to the fringes of the mainstream scene. Today’s rock musicians seem to have little or no familiarity with old-school rock ’n’ roll—regrettably, since reconnecting with the music’s roots might help restore its vigor. —"Before Elvis: the prehistory of rock 'n' roll" (2013) by Larry Birnbaum

Tom Hanks is in negotiations to play Elvis Presley’s iconic manager Colonel Tom Parker in Baz Luhrmann’s untitled Warner Bros. biopic about the legendary musician. Luhrmann will direct the movie. He also penned the script with Craig Pearce. Parker discovered Presley when he was just an unknown and quickly moved in as his lone representation. Parker was responsible for various milestones, including Presley’s record deal with RCA and his successful acting career. While Luhrmann always envisioned a star for Parker’s part, he wants a newcomer for the role of Elvis Presley. The director has begun meeting with talent for the part. Insiders say a budget is still being ironed out, but Hanks’ commitment will urge the studio to push the project forward. Luhrmann hopes to get the picture into production sometime this year. Source: variety.com