John F. Kennedy was killed on 22 November 1963, about 15m (50ft) from where we were standing on Friday, underneath the sixth-floor window from which Lee Harvey Oswald fired – or didn’t, depending on your point of view. “What hat happened in the window is not true,” said Ron Washington, holding a magazine containing grisly autopsy photographs of the 35th president of the United States. Washington has been on the case for 27 years and comes to Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas to sell conspiracy theory literature to tourists outside the former Texas School Book Depository, which is now a JFK museum. “I believe in the truth and evidence shows, indicates, Oswald’s innocent,” he said, gesturing towards the nearby grassy knoll. “Try to understand that what happened in the window was only a decoy to draw the attention away from the gunman behind the fence.” The imminent release of thousands of documents regarding the assassination is expected to shine at least a faint light on the government’s investigations, possible relationships with Oswald and his foreign trips, including a visit to Mexico City a few weeks before the shooting. Source: www.theguardian.com

Marilyn and the Kennedys – The Unequivocal Truth: Peter Lawford’s home, a $95,000 purchase in 1956 from MGM magnate Louis B. Mayer, had been the setting for Marilyn’s encounter with Bobby Kennedy, on Wednesday 4 October 1961. This occasion had also been a party to honour the Attorney General. As part of the Justice Department’s crackdown on organised crime, Bobby was in town to talk with local law-enforcement officials about the rise in mob activity in Los Angeles. Following his brother John’s favourable account of his first real meeting with Marilyn just 11 days earlier, Bobby was keen to meet the great Hollywood star himself. Although it is safe to say that the Attorney General did grow closer to Marilyn than his brother, JFK, extensive research involving their personal schedules proves that Bobby did not have a fully fledged affair with Marilyn. Moreover, details of Marilyn’s supposed encounters with Bobby’s charismatic brother, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th President of the United States, were subject to a similar level of gossip and misrepresentation.

To this day, fans, historians, documentary makers and movie columnists repeat how Marilyn grew up as an orphan in a succession of foster homes. On both counts, that was totally incorrect. In fact, in September 1937, at the age of 11, Norma Jeane was moved to West Los Angeles to live with Grace McKee’s childless 62-year-old aunt, Ana Lower. It was there that she finally found the warmth and maternal affection she had been deprived of. ‘This woman was the greatest influence on my whole life,’ Marilyn recalled in a 1962 interview with photographer George Barris. ‘I called her aunt Ana. The love I have today for beautiful and simple things is because of her. She was the only person I ever really loved with such a deep love you can give only to someone so kind and so full of love for me. One of the reasons why I loved her was because of her understanding of what really mattered in life. She didn’t believe in a person being a failure either. She believed the mind could achieve anything. She changed my whole life.’

Marilyn had been an emotionally battered woman, weaned on rejection and even cruelty in her adolescent years, but she had learned how to ride her life’s punches. There had been agents, directors, and romantic suitors who went to bat for her, who tried to protect her. But she was actually no victim, at least not of the Hollywood studio system as commonly assumed. In 1993, Ralph Roberts (her official masseur since 1959) disclosed that Marilyn had told him she had only had a one-night stand with John F. Kennedy. ‘Marilyn gave me the impression that it was not a major event for either of them,’ he remarked. In another exchange, Marilyn had announced, ‘He may be a good President, but he doesn’t grab me sexually.’ Another confidant was her former, short-term lover, newspaper columnist James Bacon, whom she confided that the President ‘made love like an adolescent.' Bacon retorted to her: ‘But Marilyn. He’s too busy running the country to be bothered about being good in bed.’ In truth, due to his excruciating back pains, intercourse and lengthy periods of foreplay were, regrettably, nigh-on impossible for the President.

Fundamental to Kennedy’s sexual inefficiencies were the persistent and well-attested problems with his back and other ailments. He suffered from osteoporosis, which seriously affected his spine and, from the age of just 20, forced him to permanently wear a brace. His back was damaged further when, on Monday 2 August 1943, during the Second World War, his torpedo boat was hit by a Japanese destroyer in the South Pacific. For 16 straight hours, Kennedy heroically managed to rescue his fellow seamen, but his bravery only managed to put more pressure on his already damaged spine. By his early 30s, the cocktail of steroids he had been consuming for colitis had accelerated his osteoporosis. His thinning bones, which had been supporting his spinal column, were now collapsing and he was now unable to perform even simple tasks. In an endeavour to ease his incessant back pain, surgeons cut open Kennedy’s back and inserted into either side of his lower spine two thin metal plates. But just three days after the operation, Kennedy developed a staphylococcus infection that spiralled out of control and he went into a coma. Within months, the back pain returned, more severe than before. After the operations, his back was weaker than ever.

When JFK moved into the White House in January 1961, he took with him eight personal physicians; doctors who would keep alive the public persona of a young, vibrant, robust President. He basked in his image of vitality and extreme good health. But in truth, it was a façade. His body was a crumbling wreck. Even the most menial of tasks could cause him great distress. By the one and only time he was intimate with Marilyn, in March 1962, President Kennedy, the most powerful man in the world, was in such disrepair that he had trouble even getting out of bed in the morning. Bending down to pull on his shoes and socks caused him immense discomfort. The thoughts of any kind of sexual intercourse outside the realms of the pool were a complete non-starter. Marilyn and JFK would never share a sexually charged session again, and Marilyn never pursued it. Openly dismissive of the former men in her life, Monroe made it clear to the few friends around her that the most significant thing for her at the start of 1962, was to move forward with her life, and that buying a home was the key to this. However, the decision to finally purchase was not entirely her own. It had actually derived from a suggestion made back in May 1961 by celebrated Californian psychiatrist Dr Ralph Greenson, the latest in a line of psychoanalysts who had managed to practise their methods on the star.

After Marilyn's divorce from her third husband, the playwright Arthur Miller, was finalized in 1961, Joe DiMaggio came back into her life and, by all accounts, desperately tried to bring some stability and calm to an existence that was veering out of control. DiMaggio was always jealous of the attention she generated from other men. He tried to get her away from people who, to his mind, were nothing but trouble (including the Kennedys), and even proposed to her, asking her to marry him again. DiMaggio had initially been drawn (like a few hundred million other men) to Marilyn's "sex goddess" person, but he was never comfortable with her flaunting it, and was a self-admitted control freak, wanting Marilyn to wear low hemlines and quit being a movie star.

Yet during their courtship, DiMaggio had worked to squelch his possessiveness, and Monroe, who spent her life in search of a father figure, a man who’d never abandon her, found that in DiMaggio. “She’d grown accustomed to his paternalistic guidance and the protective side of his personality,” said Monroe’s close friend dancer Lotte Goslar. “And here was a father figure with whom she could have sex. And the sex was pretty damn good, as she said herself.” DiMaggio never stopped trying to win her back and he started therapy for anger management. In February 1961, when Monroe—who’d been diagnosed by two top psychiatrists as a paranoid schizophrenic like her mother—was forcibly institutionalized in New York City, DiMaggio answered her calls for help. In July 1962, a close friend of DiMaggio’s remarked, ‘Joe never sold his home there, the one he wanted for Marilyn. He has never stopped talking about her over the years. I think he believes she’ll eventually find herself and return to him. He’ll wait.’ During the afternoon of 1 August, 1962, now tired of waiting, DiMaggio excitedly flew out to Los Angeles and headed straight to Marilyn’s home in Brentwood where he asked for her hand in marriage. But although appreciative, Marilyn dismissed his offer outright and told him she wished to remain a friend only.

Though there were no doubts that DiMaggio was her best and most trusted friend, the chances of them ever remarrying were very remote indeed. Probably she had no desire to remarry DiMaggio because, put simply, she was no longer in love with him. She saw him now only as a close, platonic friend. And DiMaggio was totally devastated. Genuinely believing she would accept his proposal and imagining he would spend the entire day (and the rest of his life) with the actress, he had cancelled his appearance at that evening’s Fifth Annual Boys’ Invitational Baseball Tournament at Shepherd Stadium in Colonial Heights. His no-show naturally took everyone by surprise. It was something the ever-reliable Joe never did. With Marilyn’s rejection still ringing in his ears, he dejectedly left her home, heading out to San Francisco to prepare for an old-timers’ baseball game which was due to take place at Candlestick Park on Saturday. —"Marilyn Monroe: The Final Years" (2012) by Keith Badman

To this day, fans, historians, documentary makers and movie columnists repeat how Marilyn grew up as an orphan in a succession of foster homes. On both counts, that was totally incorrect. In fact, in September 1937, at the age of 11, Norma Jeane was moved to West Los Angeles to live with Grace McKee’s childless 62-year-old aunt, Ana Lower. It was there that she finally found the warmth and maternal affection she had been deprived of. ‘This woman was the greatest influence on my whole life,’ Marilyn recalled in a 1962 interview with photographer George Barris. ‘I called her aunt Ana. The love I have today for beautiful and simple things is because of her. She was the only person I ever really loved with such a deep love you can give only to someone so kind and so full of love for me. One of the reasons why I loved her was because of her understanding of what really mattered in life. She didn’t believe in a person being a failure either. She believed the mind could achieve anything. She changed my whole life.’

Marilyn had been an emotionally battered woman, weaned on rejection and even cruelty in her adolescent years, but she had learned how to ride her life’s punches. There had been agents, directors, and romantic suitors who went to bat for her, who tried to protect her. But she was actually no victim, at least not of the Hollywood studio system as commonly assumed. In 1993, Ralph Roberts (her official masseur since 1959) disclosed that Marilyn had told him she had only had a one-night stand with John F. Kennedy. ‘Marilyn gave me the impression that it was not a major event for either of them,’ he remarked. In another exchange, Marilyn had announced, ‘He may be a good President, but he doesn’t grab me sexually.’ Another confidant was her former, short-term lover, newspaper columnist James Bacon, whom she confided that the President ‘made love like an adolescent.' Bacon retorted to her: ‘But Marilyn. He’s too busy running the country to be bothered about being good in bed.’ In truth, due to his excruciating back pains, intercourse and lengthy periods of foreplay were, regrettably, nigh-on impossible for the President.

Fundamental to Kennedy’s sexual inefficiencies were the persistent and well-attested problems with his back and other ailments. He suffered from osteoporosis, which seriously affected his spine and, from the age of just 20, forced him to permanently wear a brace. His back was damaged further when, on Monday 2 August 1943, during the Second World War, his torpedo boat was hit by a Japanese destroyer in the South Pacific. For 16 straight hours, Kennedy heroically managed to rescue his fellow seamen, but his bravery only managed to put more pressure on his already damaged spine. By his early 30s, the cocktail of steroids he had been consuming for colitis had accelerated his osteoporosis. His thinning bones, which had been supporting his spinal column, were now collapsing and he was now unable to perform even simple tasks. In an endeavour to ease his incessant back pain, surgeons cut open Kennedy’s back and inserted into either side of his lower spine two thin metal plates. But just three days after the operation, Kennedy developed a staphylococcus infection that spiralled out of control and he went into a coma. Within months, the back pain returned, more severe than before. After the operations, his back was weaker than ever.

When JFK moved into the White House in January 1961, he took with him eight personal physicians; doctors who would keep alive the public persona of a young, vibrant, robust President. He basked in his image of vitality and extreme good health. But in truth, it was a façade. His body was a crumbling wreck. Even the most menial of tasks could cause him great distress. By the one and only time he was intimate with Marilyn, in March 1962, President Kennedy, the most powerful man in the world, was in such disrepair that he had trouble even getting out of bed in the morning. Bending down to pull on his shoes and socks caused him immense discomfort. The thoughts of any kind of sexual intercourse outside the realms of the pool were a complete non-starter. Marilyn and JFK would never share a sexually charged session again, and Marilyn never pursued it. Openly dismissive of the former men in her life, Monroe made it clear to the few friends around her that the most significant thing for her at the start of 1962, was to move forward with her life, and that buying a home was the key to this. However, the decision to finally purchase was not entirely her own. It had actually derived from a suggestion made back in May 1961 by celebrated Californian psychiatrist Dr Ralph Greenson, the latest in a line of psychoanalysts who had managed to practise their methods on the star.

After Marilyn's divorce from her third husband, the playwright Arthur Miller, was finalized in 1961, Joe DiMaggio came back into her life and, by all accounts, desperately tried to bring some stability and calm to an existence that was veering out of control. DiMaggio was always jealous of the attention she generated from other men. He tried to get her away from people who, to his mind, were nothing but trouble (including the Kennedys), and even proposed to her, asking her to marry him again. DiMaggio had initially been drawn (like a few hundred million other men) to Marilyn's "sex goddess" person, but he was never comfortable with her flaunting it, and was a self-admitted control freak, wanting Marilyn to wear low hemlines and quit being a movie star.

Yet during their courtship, DiMaggio had worked to squelch his possessiveness, and Monroe, who spent her life in search of a father figure, a man who’d never abandon her, found that in DiMaggio. “She’d grown accustomed to his paternalistic guidance and the protective side of his personality,” said Monroe’s close friend dancer Lotte Goslar. “And here was a father figure with whom she could have sex. And the sex was pretty damn good, as she said herself.” DiMaggio never stopped trying to win her back and he started therapy for anger management. In February 1961, when Monroe—who’d been diagnosed by two top psychiatrists as a paranoid schizophrenic like her mother—was forcibly institutionalized in New York City, DiMaggio answered her calls for help. In July 1962, a close friend of DiMaggio’s remarked, ‘Joe never sold his home there, the one he wanted for Marilyn. He has never stopped talking about her over the years. I think he believes she’ll eventually find herself and return to him. He’ll wait.’ During the afternoon of 1 August, 1962, now tired of waiting, DiMaggio excitedly flew out to Los Angeles and headed straight to Marilyn’s home in Brentwood where he asked for her hand in marriage. But although appreciative, Marilyn dismissed his offer outright and told him she wished to remain a friend only.

Though there were no doubts that DiMaggio was her best and most trusted friend, the chances of them ever remarrying were very remote indeed. Probably she had no desire to remarry DiMaggio because, put simply, she was no longer in love with him. She saw him now only as a close, platonic friend. And DiMaggio was totally devastated. Genuinely believing she would accept his proposal and imagining he would spend the entire day (and the rest of his life) with the actress, he had cancelled his appearance at that evening’s Fifth Annual Boys’ Invitational Baseball Tournament at Shepherd Stadium in Colonial Heights. His no-show naturally took everyone by surprise. It was something the ever-reliable Joe never did. With Marilyn’s rejection still ringing in his ears, he dejectedly left her home, heading out to San Francisco to prepare for an old-timers’ baseball game which was due to take place at Candlestick Park on Saturday. —"Marilyn Monroe: The Final Years" (2012) by Keith Badman

Scientists pinpoint jealousy in the monogamous brain: Shakespeare's “green-eyed monster” has been written about for centuries, but the scientific study of jealousy is relatively young. Jealousy may have given a fitness advantage to humans in our ancestral environment; current evidence shows that culture also plays a role. “Understanding the neurobiology and evolution of emotions can help us understand our own emotions and their consequences,” says Dr. Karen Bales from the University of California, USA. Unrestrained jealousy can have negative health effects and in extreme cases can even lead to violence. But jealousy also plays a positive role in social bonding, by signaling that a relationship may need attention. It may be particularly important for keeping a couple together in monogamous species like humans. “The neurobiology of pair bonding is critical for understanding how monogamy evolved and how it is maintained as a social system,” says Bales.“ The researchers found that in the jealousy condition, the monkeys’ brains showed heightened activity in an area associated with social pain in humans, the cingulate cortex. “Increased activity in the cingulate cortex fits with the view of jealousy as social rejection,” she adds. “Monogamy probably evolved multiple times so it is not surprising that its neurobiology differs between different species,” says Bales. “However it seems as though there has been convergent evolution when it comes to the neurochemistry of pair bonding and jealousy.” Source: blog.frontiersin.org

"When I kissed her and told her I loved her, Patti, my Princess, looked into my eyes and I knew my life was first beginning. The letters I received were as important to me as was medicine to a sick man. Time moved slowly… We would meet in New Haven, New York, Boston, whenever we could get away. Our love was so wonderful we thought that surely we were the first to love. The only thing we dreamt about was to get married. We had nothing but our love. There were many times through the ensuing years that I hung onto those words: 'I love her.' My feelings, where my wife is concerned, are very deep and very sacred. She is the very reason I live for she is the only reason I know that makes living worth anything… and the boys are equally worth it, but one day they’ll leave and then there will be only us."

"I can only answer “God” honestly, and he knows my worth and my intentions, I have no fear of his wrath for I know he knows I’m basically good. Patti is the first human being that has ever cared about me or for me… Oh, there were a few beings that cared, but not enough that I could have survived. It was only when she came into my life that I realized I had a life… I want so much to scream the things that tug away at my heart and my soul… And when I try, the hurt is so strong, and deep, and festered that I clam up, and the relief I want doesn’t come… But I am a very lucky man to have found the real, right, and perfect human being to spend my years with. I want so much to do the right thing to keep her straight and happy… The only emotional thing that can kill me is when she hurts… or when I’ve caused her pain… but my intentions are never to hurt her, never to do her a moment’s pain, never to create a frown on her lovely face…" —JUST 'CAUSE I LOVE HER by Jerry Lewis (July 4, 1951)

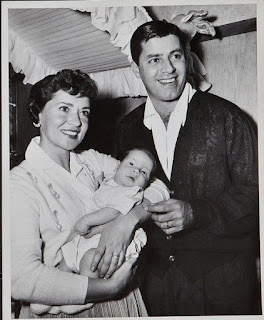

"Friends remember Jerry as being ultra-possessive of me in the early days of our marriage. As the children came along, they saw him as jealous of the time I committed to them. But just when I would start to agree with my friends, I would get a loving note from Jerry about how much he cared for me and the pride he had in my being a good mother. These mixed messages had kept me from separating from Jerry long before we met in court." —"I Laffed Till I Cried" (1993) by Patti Lewis

On February 24th, 1953, Marilyn was awarded the Red Book magazine award for Best Young Box Office Personality. Her presentation as a special guest was made at the end of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis' radio show (there still is an audio recording available). Marilyn was excellent, and even played Jerry's girlfriend in a live skit on the show. Also there was a lot of 'off the cuff' stuff, the three performers hanging out socially in Beverly Hills. Jerry Lewis would comment about his friendship with Marilyn on Bill O'Reilly's and Larry King's talk shows. On neither occasion did he admitted to sleeping with Marilyn, although Lewis was adamant about defending her. In Marilyn Monroe: A Never-Ending Dream (1986), Marilyn confessed to historian/writer Guus Luijters she had found Jerry Lewis "quite sexy."

The Martin and Lewis Show (1953): Dean Martin reveals the identity of the show's secret guest to Jerry Lewis: Marilyn Monroe. Martin and Lewis talk about the cotton dress Marilyn is wearing and her new movie "Niagara"; Lewis attempts to get her to go out on a date with him; Lewis, Martin, and Monroe perform in a sketch about the newspaper editor of the "Daily Hangover" (Jerry Lewis) whose love interest is his star reporter (Marilyn Monroe). Extracted from the radio show's transcript — Marilyn: 'I'm a blonde, and I like to go out with tall, dark, handsome men. You see, opposites attract.' Jerry Lewis: 'Then you'll love me. I'm just the opposite.' Marilyn: 'Look Jerry, you're a man, and I'm a woman.' Jerry Lewis: 'Now that we've chosen sides, let's play.' Dean Martin: 'Won't you give up, Jerry. Marilyn prefers me. I've gone out with women that would not even look at you.' Jerry Lewis: 'So what? I've gone out with women who wouldn't look at me either.' Dean Martin: 'Giving her a kiss doesn't increase the newspaper circulation.' Jerry Lewis: 'But increases mine!' (laughter)

Jerrry Lewis was a perfectionist. But he also showed signs of obsessive compulsive disorder and depressive episodes. Some of his close colleagues thought his brand of childish comedy was a sign of escapism. He had felt like “a dummy, a misfit, the sorriest kid alive” during his childhood. A psychiatrist once even warned him off therapy, saying: “If we peel away the emotional and psychological difficulties, your pain may leave, but it’s also quite possible that you won’t have a reason to be funny any more.” Jerry revealed he had beaten himself up “a thousand times” over his son Joseph’s death, adding: “I’ve worked under the most painful conditions any man has ever felt in his life. But when I walk out on that stage, the pain goes away.” Often ostracized in his late career for his stubborn opposition to the postmodern trends in Hollywood, frequently neglected in an everchanging film industry and overlooked as iconoclast filmmaker in America, he would be vindicated by the likes of Martin Scorsese, who referred to Lewis as "one of the truly greats." To his credit, Lewis was one of the few writers who didn't use systematically his artistic medium as a scoreboard for his grudges or intimate foibles. Obviously, he projected on occasion some of his personal fears or fantasies, but it's not enough to trace a semblance of autobiographical realism through his filmography in any case.

Jerry Lewis loved to work with segmentation, to divide the frame into separate compartments (the line between stage and backstage in the prom scene of The Nutty Professor, the recording studio scene in The Patsy). Another instance: Music disappears from the soundtrack when a girl disappears around a corner with her transistor radio in The Ladies Man. Lewis's great originality as a filmmaker lies in his art of multiplying segmentation or segmenting multiplicity so as to produce a spiraling disorder that leads miraculously to a reassertion of order (as in the endings of The Family Jewels, Which Way to the Front?, and Cracking Up). His films take place in zones of indeterminacy and combinatorial freedom. In The Total Film-Maker, Lewis called the pattern formed by the comic performer "an erratic pattern." If the confessional aspect of The Nutty Professor and the self-reflexivity of films such as The Errand Boy and The Patsy have often encouraged viewers to see Lewis's work as a distorted autobiography, a set of mirror fictions in which he externalizes various aspects of himself, his films make an equally strong demand to be read as the most vivid and emotionally wrenching American show-business hallucinations ever put on film: representations of a modern world, partly real, partly staged. The Bellboy, The Errand Boy, The Nutty Professor, The Patsy, Three on a Couch, and The Big Mouth are comic masterpieces that propose a rich and haunting combination of realms and values without ceasing to coexist within a single frame. These films do not, and are not made to, offer the reassurance of a cohesive narrative controlled by a stable authorial agency. They set up, instead, a liberating and exhilarating confusion of realms, in which Jerry Lewis (the author), too, is one of the figures that swim in and out of focus. Source: www.movingimagesource.us