Decades of psychological research has revealed that different facial expressions can communicate different emotional intents. Smiles are arguably the most important facial expression, given their frequent use in day-to-day interpersonal interactions. What exactly constitutes a “successful smile”? In a recent study from the University of Minnesota, Professor of Psychology & Statistics Nathaniel Helwig concludes: The results reveal that no single smile is "perfect" compared to the others. Instead, there exists a window of parameters, or “smile sweet spot,” which creates successful smiles. We observed somewhat of a Goldilocks Phenomenon, such that successful smiles needed just the right amount of teeth. Also, we found that too much smile angle and extent produced fake and creepy smiles. Interestingly, we discovered that smiles with slight timing asymmetries are more successful than perfectly symmetric smiles, but asymmetries larger than 125 milliseconds were detrimental. Past research has revealed that the eyes are important—particularly for distinguishing between “Duchenne” (genuine) versus “Pan Am” (fake) smiles. Our results reinforce the idea that the lower half of the face, particularly mouth movement, is a prominent factor for determining the emotional intent of a facial expression. Source: www.researchgate.net

In the bestselling tradition of Henry Bushkin's Johnny Carson comes The Way It Was: My Life with Frank Sinatra, a candid and eye-opening inside look at the final decades of Sinatra's life, told by Eliot Weisman, his long-time manager and friend. Weisman worked with Frank Sinatra from 1975 up until Sinatra's death in 1998, and became one of the singer's most trusted confidantes and advisers. In this book, Weisman tells the story of the final years of the iconic entertainer from within his exclusive inner circle--featuring original photos and filled with scintillating revelations that fans of all Sinatra stages--from the crooner to the Duets--will love. Capitol/UMe announced a new collection from Frank Sinatra set for release on October 6. Ultimate Christmas collects 20 of the Chairman’s seasonal standards from both his Capitol and Reprise periods, spanning 1954 to 1991, including collaborations with his children Frank Jr., Tina, and Nancy. Source: www.amazon.com

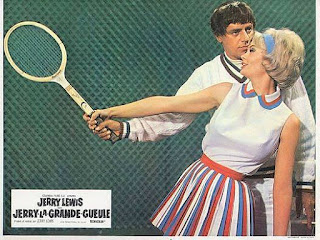

Jerry Lewis clowns around behind the bar at the Copacabana nightclub in New York City. The paths of Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra crossed at the Copacabana in 1948 when Sinatra appeared with the comedian Jerry Lewis. Sinatra thought Lewis was great, the creative dynamo in the tandem Martin & Lewis. “The Dago’s lousy,” Frank said of Dino. However, Frank’s friendship would in time develop with Dean, not Jerry. As writer William Schoell said, “Frank would naturally gravitate to another cool ‘wop’ like Martin than to a crazy, difficult Jew like Lewis.” A reporter once asked Dean just how close he was to Frank. “He is my dearest, closest friend,” Dean claimed. Ironically, Frank’s career in 1952 was on the rocks, but Jerry and Dean were reaching the peak of their popularity. Dean’s second wife, Jeanne Martin, said her husband “had great admiration for Sinatra as a singer, but had no respect for him as a man.” After their split, Jerry Lewis accused Dean of professional jealousy: “I’m sure he felt I was writing the material to build myself up. I’m sure I did things to irritate Dean, but in this matter, my hands are clean. As producer Hal Wallis and others know, I leaned over backwards to give Dean more to do at my own expense.”

Martin & Lewis, despite multimedia triumph, couldn't last: while Jerry loved Dean like a brother, feckless, unreliable Dean said "To me, you're nothing but a dollar sign" which led Jerry to break out of their association. The Martin and Lewis partnership lasted 10 years. Professional jealousy and assorted other tensions brought it to an end, bitterly, in 1956, and although the two attempted occasional cordial meetings, the split lasted the rest of their lives. When Dean became an integral part of the famous Rat Pack clan, he had joked, “Frank is the rat. I am the pack.” Frank was especially interested in hearing about Dean’s experiences with women he had not yet seduced. Dean's conquests included such stars as Pier Angeli, Dorothy Malone, Lori Nelson, Jill St. John, Jacqueline Bisset, and even June Allyson, America’s “sweet-heart” in the mid-1940s. Dean Martin appeared at the Sands in Las Vegas with a bevy of showgirls. Unaware that Montgomery Clift (Dean Martin's co-star in The Young Lions) was a homosexual, Dean told Sinatra: “I at first thought he was fucking Elizabeth Taylor.” In Hollywood, a guy marries a somewhat plain woman who will stand by him on the way up. But when he arrives at the big time, he can go for the sultry siren type. Frank Sinatra was the perfect example of that—from Nancy Barbato to Ava Gardner.

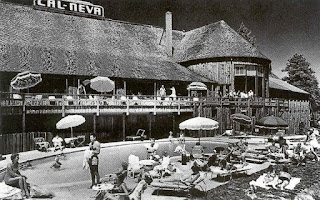

Frank would later assert to Playboy, “You can be the most artistically perfect performer in the world, but an audience is like a broad—if you’re indifferent, endsville.” Frank persuaded Dean to become part owner of the infamous Cal-Neva Lodge on the border between California and Nevada (the casino was carefully positioned in Nevada). Dean purchased seven percent interest in the lodge. He later learned that Frank owned one-quarter of the real estate. When Dean learned of the mob’s association with Cal-Neva, Dean asked Frank if he could pull out. Frank said he’d make arrangements to have someone else take over Dean’s interests. Introduced to him by Frank, Dean found sex goddess Marilyn Monroe a bit too exotic for his tastes. But in time he'd enter her web of intrigue and emotional dependency. He visited her apartment with a rewritten script of My Favorite Wife, which had starred Cary Grant and Irene Dunne in 1940. My Favorite Wife had been retitled Something’s Got to Give (Marilyn's last film). Originally Fox wanted James Garner for the part, but Marilyn held out for Dean Martin. The blonde goddess had every intention of finishing the movie before Fox fired her for holding up production. She even told Martin that she planned to follow their movie with another script called What a Way to Go, which would costar Frank Sinatra.

Marilyn crossed out entire pages within her copy of the original script, telling director George Cukor, “It’s unbelievable. Dean Martin would never be attracted to another woman if he had me.” After endless delays on the set, including times when Marilyn didn’t even show up, director George Cukor told Dean he wanted to replace Marilyn with Lee Remick or Kim Novak, Frank’s former girlfriends. Dean held out for Marilyn. “If Marilyn is fired, I walk,” he warned Fox executives. Dean went into a deep depression when he heard of Marilyn’s death on August 4, 1962. He tried to attend the funeral with Frank but Joe DiMaggio had left orders for security guards to bar both of them.

Frank Sinatra called January 25, 1990, the “saddest day of my life.” He’d just put down the phone after a call from London. His beloved Ava had died of pneumonia at the age of sixty-seven. Shortly before her death, she told a reporter, “I drank too much, partied too much in the Fifties. It’s all caught up with me. I didn’t age well, honey child. I was never that great an actress. Now, I’m what is called a faded beauty.” Sinatra, in one of the low points of his career, had joined up with Bogart’s Rat Pack in 1953. After Humphrey Bogart died of cancer in 1957, the original Rat Pack more or less dissolved. Bacall pronounced it “gone forever.” Unlike Bogie’s Rat Pack, which was purely social, Sinatra’s Rat Pack often performed together, either on stage or in the movies. Frank set the rules for the club. The drink of choice was a bottle of Jack Daniels. The dress code was crisp white shirts, shiny sharkskin suits, and thin dark ties. Dean warned Frank, “Don’t ever let Jerry Lewis become a member—or else I’m out of here.” Of all the Rat Packers performing on stage, Peter Lawford was viewed as the least talented—“a louchemeister of limited gifts who was there only because he was married to JFK’s sister,” in the words of one critic.

As Patti Lewis recalled: “Jerry accused me of having an affair with Dean. I did not. We were like family. Dean tried, in his own way, to offer me support, and just knowing someone else was aware of what was going on eased my pain. It also created a bond between us and helped me understand Dean’s feelings.” If Patti understood Dean’s feelings, it may have been, in part, because of their shared experience as show people born to Italian immigrants. Dean and Patti recognized each other across that noisy table at Lindy’s. They were cut from the same cloth, however differently they wore it. Patti might have reminded Dean of his mother. There was nothing sexual between them—Dean usually went for blondes—but that Jerry was married to such a woman surely raised him a notch in Dean’s eyes.

Unknown to many, Marilyn Monroe became a temporary but rather unstable member of the Rat Pack. Columnist Dorothy Kilgallen, an enemy of Frank’s, wrote that he dated some of the great beauties and stars of their day, including Marilyn and Lana Turner. “Others,” she claimed, “were fluffy little struggling dolls of show business.” Although Joe DiMaggio socialized with Sinatra, he never completely trusted him, especially around Marilyn, causing a rift in the trio. Marilyn wanted to film What a Way to Go with Sinatra, but one night she decided that she preferred Gene Kelly as her co-star. At 20th Century Fox, executives wanted to co-star Marilyn and Sinatra in Pink Tights, a remake of Betty Grable’s 1943 Coney Island. Marilyn was open to the idea of co-starring with Frank in a film in which her character evolves from a prim schoolteacher to a torch-singing cabaret artiste.

Privately, Frank had told Dean Martin and others, “I wish Marilyn would divorce Joe. He’s not right for her. For Marilyn to give up her career—now that’s making the big sacrifice.” Frank was playing a dangerous game, being Marilyn’s confidant and protector on the one hand, and DiMaggio’s good pal on the other. Frank allegedly told his friend Jilly Rizzo that he wanted to keep information about his sexual involvement with Marilyn private from DiMaggio. “I don’t need the aggravation. Joe would get seriously pissed off at me. Of course, if Marilyn and I get really serious about this thing, Joe is gonna find out. If she becomes the next Mrs. Frank Sinatra, the whole fucking world will know. Joe already suspects us. He’s not as dumb as he looks.” Marilyn’s secretary and confidante, Lena Pepitone, who wrote a book entitled Marilyn Monroe—Confidential in 1979, claimed that she asked Marilyn why she would consider marrying Frank if she were still in love with DiMaggio. “Joe loves me, but he’s insisting I give up my career. I’ll never do that.” Ironically, Frank, if he’d agreed to marry her, would have insisted that Marilyn give up her career, too. During the last vacation weekend of her life, Frank invited Marilyn to the Cal-Neva Lodge, whose location straddled the border between California and Nevada. When DiMaggio heard of this, he too headed there.

He’d told friends about Sinatra and his influence on his ex-wife Marilyn, “why doesn’t he let her alone? He’s only fucking up her mind. And those are gangsters he’s got her mixed up with!” DiMaggio was no doubt referring to mob boss Sam Giancana who was a guest at the Lodge that weekend. On Sunday, September 18, Frank’s voice, but not Frank, joined Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis on a historic episode of The Colgate Comedy Hour. This was the show where Martin and Lewis, who were in the midst of epic battles and had less than a year to survive as a comedy team, seemed to declare an uneasy truce in a skit spoofing the quiz show The $64,000 Question. When Dean, playing the emcee, pushes Jerry, as the contestant, underwater in a dunk-tank isolation booth, Jerry rises up and splutters, “Haven’t you heard? The feud is over!” In a poolroom sketch later, Jerry, purporting to be a songwriter, tries to sell Dean a goofy tune called “Yet I Can’t Forget Her.” As delivered by Lewis in his Idiot Kid mode, the song is pure malarkey, but when he turns on a radio the next moment, there’s Sinatra singing it, quite charmingly. Frank Sinatra, who was almost incapable of ad-libbing a comic line onstage, envied Jerry Lewis' comedic talents.

To Frank Sinatra, who always seemed to be crying or killing himself over a woman, who always seemed to be dispatching others to do his dirty work, whose mammismo relationship with his mother was that of a little boy—Dean was la cosa vera, the real thing, the right stuff. Ohio-born Dean Martin had been a former prize fighter and card shark reconverted into suave crooner. As for Dean’s feelings about Frank—well, who knew? He certainly admired him as a singer. Yet, Nick Tosches contends, Martin felt Sinatra “took it all so fucking seriously. He thought he was a fucking artist, a fucking god.” And while Frank’s charisma, volatility, and huge success in the 1950s made him a natural leader, with a group of followers who jumped at his every wish—and often flinched when his temper flared—Dean Martin wasn’t one of them. Though both Sinatra and Martin had dropped out of high school in the tenth grade, Frank possessed a restless, ravening intellectual curiosity; Dean loved watching Westerns on TV and reading comic books. —"Sinatra: The Chairman" (2015) by James Kaplan

“Dean doesn’t have an overwhelming desire to be loved,” Dean's second wife Jeanne said. “He never had a male friend,” Jeanne asserted flatly. Nick Tosches punts on the issue: “He was close to Mack Gray, to Sammy Cahn, to Frank Sinatra, to others,” he writes. “But he did not need friendship.” Jerry Lewis, like Frank Sinatra, was an only child and once said that Dean Martin was the big brother he never had. Sinatra looked up to Martin in similar ways. A song Cahn and Van Heusen would later write for Frank put it unapologetically: “I like to lead when I dance.” With Martin and Lewis, the dance had ended badly. With Martin and Sinatra, the dance went on and on. Jerry Lewis was the most vulnerable of the three performers. Before teaming with Martin, Lewis had toured the vaudeville circuit with a “record act” in which he played back the recorded voices of popular singers and accompanied them with his own exaggerated pantomime. The idea had come while he was romancing Lonnie Brown in her bedroom. These performances undoubtedly not only parodied the sentiments the songs were meant to evoke but revealed the constructed, performed, and artificial nature of the person who was supposed to be exteriorizing these sentiments (thereby subverting the ideology of individuality). In these “Satirical Impressions in Pantomimicry,” Lewis presented himself as a partial or composite being—a personality that existed because of, and through a difference from, another personality. Foregrounding this difference exposed the fictive nature of both personalities.

"Love and laughter has to be what it's all about. Then you'll survive. Maybe we'll all survive. Maybe. But the touch question when dealing with people is: 'How do I know when I'm human enough?' I'm going to use a wrong word because that's the way I want to use it, letting the language purists feel superior. The word I'm talking about is humanities. There is a great deal of confusion between humanism, which means a cultural attitude, and humanity, which really means a kindly disposition toward your fellow man. I maintain we're dealing in a humanities area just as critical, in its way, as open-heart surgery. I don't care how much technical information you have stored away, you blow the picture when you blow the human end. I am not ashamed or embarrassed at how seemingly saccharine something in my films will sound. Actors are a strange breed of people. If you want to attempt to understand actors, read a quote from Moss Hart's Act One: 'The theatre is an inevitable refuge of the unhappy child, and the tantrums and childishness of theatre people are not either accidental nor a necessary weapon of their profession. It has nothing to do with so-called artistic temperament. The explanation, I think, is a far simpler one. For the most part, they are impaled in childhood like a fly in amber.' But there's a contradiction, too. They are there so that everyone in the world can watch them, yet at the same time no one should be permitted to see them act. Actors are very complex people."

"I do love to act, however. Why? There is a tremendous satisfaction in making people laugh. It feels good. The best way to photograph a woman is dead-on and close. A low angle on a woman often distorts. Women are tough to shoot. There is still another misconception in cut coverage, one of those rules to be broken: it says that the director make a single shot of the male if he has made a single of the female. I prefer to do a single of the female and relate her to the male with an over-on, over her on him, at the same time keeping a single of her. With two singles there is no direct tie between the characters. Too many beginning directors play with their cameras, moving them to let the audience know the camera is moving. They should have their hands broken, should have the cameras dumped on them. Again, it is that kid's shout, 'Hey, lookit me!' George Stevens, in directing A Place in the Sun, Giant and The Greatest Story Ever Told, shows mastery in almost every frame, and the viewer, whether or not he enjoys the film or the subject matter, is unconsciously aware of the fine stitching throughout. I respect Hitchcock and his superb talents but he crossed the line of decency and I hate some of his films. I hated Psycho, although it was a good movie. After seeing it at the DeMille Theater in New York I went to a bar and shook a brandy down. I couldn't enter the bathroom in the hotel without shuddering."

"Make enough films, even if you are Robert Wise, and you'll bomb once in a while. There are many directors not in the category of a Robert Wise, a William Wyler, a George Stevens or a Zinnemann who turn out fine pictures and may someday do their classic. Ninety percent of the avant-garde clique who proclaim, 'Look at the greatness of his film,' are ashamed to admit they don't know what the hell it is all about. They can't wait to run to the coffeehouse to breathe out, 'Wasn't that magnificent?' God forbid someone asks, 'What did it mean?' There's a long silence. Then some creep with a beard and thick lenses says, 'What's the difference?' Insofar as an eight-hour Andy Warhol film is concerned, I lump the avant-garde and the underground in the category of film users rather than filmmakers. Often they are using film indulgently for no other purpose than to create controversy."

"Maybe, for some of us, after we cut away the drivel, comedy is our bag because it is in our gut. We have no choice. It's laugh or cry. People can't hate when they are laughing. A good comedian, I think, comes from a shallow beginning if not a minority group. Shallow emotionally or financially, often both. No one from a silver-spoon family has ever been a top banana. A few have tried but haven't made it. Comedy, humor, call it what you may, is often the difference between sanity and insanity, survival and disaster, even death. It's man's emotional safety valve. If it wasn't for humor, man could not survive emotionally. Peoples who have the ability to laugh at themselves are the peoples who eventually make it. I also feel there is nothing more dramatic than comedy. There must also be relief from laughter as opposed to comic relief. An audience cannot be allowed to laugh too long, or too hard, within anyone period of time. Rolling in the aisles comes from laughter but it also comes from the inability to handle it. There are times when slight laughter is better than a lot of it."

"When my crew are looking at me with some kind of envy: 'Look at this confidence. Cocksure. What he knows he's going to do, he's going to do.' They should only know that 60 percent is confidence. Forty percent is crap. The world is still made up of green apples and dreams and wishing wells; the heart beats fast when a pretty girl winks. All of that is still what it is all about. The important things, the ones some people put down, are the lovely, wonderful things that gives gooseflesh. Sometimes I have been accused of being morally theatrical. I hate that. I’m moral. I like to think I’m moral. There’s a wonderful line: “I care about the demise of a man because I’m involved with mankind.” My involvement is genuine, it’s sincere. I feel that if you’re given a special place in this life, you can’t walk into a small room and close the door with it. I think that’s wrong. Because it’ll be of no consequence to yourself or anyone else, unless you use that gift. Use it how? To get another gift? No, you use that gift to spread the word that made you the recipient of the gift. So I’m kind of idealistic, mid-Victorian, completely old-fashioned. I’ve gotten further with truth than a thousand people hedging, fudging. When you learn, and I have, truth is immediate. Most of the characters that I played had truth as a foundation. Cagey, maybe; but never deceptive. His truth was part of his innocence. And certainly part of his naivety." —"The Total Film-Maker: The New Collectors Edition" (2017) by Jerry Lewis

Whether he appeared in his own films or not, Lewis’s directorial style was too drastic, uncompromising, and strong for even a self-reinventing Hollywood. Like all narratives, the Lewisian narrative, however thwarted or vestigial it may be, poses and answers a question. But in Lewis’s work, the question becomes forgotten or displaced. In The Ladies Man, the master question—Can Herbert get over his problem with women?—is simply dismissed, as Herbert finds himself in a house surrounded by women who overcome his reluctance and persuade him to stay. The Patsy and Cracking Up are especially interesting as the two Lewis films in which he directly confronts the possibility of his own character’s death (as he does, more obliquely, in The Family Jewels and The Big Mouth): the films try to define and preserve selfhood even as they play with its disappearance, only to end up acknowledging the fictional and optional nature of selfhood and (like Three on a Couch) the untenability of any standard of “success.” Though based on a routine premise, The Big Mouth reaffirms Lewis’s commitment to the absurd and his independence from Hollywood norms of narrative and characterization. The possibility that individuality could be eradicated or annulled always lies underneath the dazzling variety of Lewis’s playful constructions of identity.

Where does life end and performance begin? The Errand Boy and The Patsy propose a continuity between the two. The famed columnist Hedda Hopper tells Stanley’s handlers in The Patsy: “You’ve come across somebody who hasn’t yet learned to be phony. He felt something, and he said it, which was real and honest. And now if you apply that to his performance, you’ve got a great success.” The Errand Boy is neither a celebration nor an evisceration of Hollywood; it is a mourning of it, a lament for its disappearance. One of Lewis’s innovations is making the showbusiness id the instrument and the vehicle of a superior alternate model of self-realization to that of psychoanalysis. In The Errand Boy, Morty’s encounter with Magnolia steers the film away from slapstick and toward a low-key existential meditation, with overtones of the possible beginning of a romantic relationship. Lewis’s semi-documentary style through several films (The Bellboy, The Errand Boy, Hardly Working) marks him as one of the major pop-modernists of American cinema, along with Howard Hawks, Frank Tashlin, and Andy Warhol. In his love scene with Pat Stanley's character in The Ladies Man, Herbert is trying desperately to be that young man that might be her possible choice. The tracking shot of the car wash in The Errand Boy celebrates the sleekness of modernity, aligning the film with some of the major themes of American pop culture (see also the parody rock song “I Lost My Heart in a Drive-in Movie” in The Patsy).

It’s worth rehearsing how so much of the plot from The Patsy obviously meant to mirror Jerry’s own experience of Hollywood while touching on his favorite narrative themes—the cynical handlers, the clown who comes through with sincerity when his act fails, the women who want to burp him, the lying sycophants and journalists, the absurd means by which nobodies become stars. The film features several Hollywood stars playing themselves—Rhonda Fleming, George Raft, Mel Tormé, Ed Wynn—yet the script asks them all to play phonies. Hedda Hopper appears at a cocktail party with an absurdly oversized hat, and only Stanley has the effrontery to laugh at it. The routine on the Sullivan show is truly bizarre. Stanley, trained as a stand-up comic, is so bad that crickets can be heard chirping in the background at one of his club dates, but suddenly he’s able to pull off a long silent comedy routine with no rehearsal. Even in the logically unstable world of Jerry Lewis (which more than one critic has compared to that of Lewis Carroll), this is hard to rationalize. There was about The Patsy an air of self-deprecation that none of his other projects had.

“Jerry Lewis as The Patsy,” read the opening titles, and the audience can make that identification on several levels. This was not just a simple reappearance of the Kid in a new setting; this was a mature man coming to grips with the fact that his career was built on ephemera and boosted by liars. It’s no wonder the film’s box office was among the softest yet for a Jerry Lewis picture. The pratfalls and silly walks that Lewis devised to delight us movie after movie, resulted in back injuries—not to mention addiction to painkillers—that essentially led to lifelong pain. Being funny hurts. But Lewis was really a musician and dancer rolled into one, even when he was neither playing music or dancing outright. His routines were a glorious rush of improvisatory looseness and seemingly contradictory precision: He’d know intuitively when to cross his eyes or jut his jaw, and if his split-second decisions were as definitive as a well-placed sixteenth note, they also felt wild and a little dangerous, an invitation to reckless freedom and joy. And Jerry went on alone to be writer-director-star, to flop on TV, to labor for Muscular Dystrophy research, to raise a big family, to fight show-biz segregation. As for his moviemaking decline, Jerry blamed Hollywood's "corporate structure." —"Jerry Lewis: The Total Film-Maker" (2009) by Chris Fujiwara

_01.jpg)