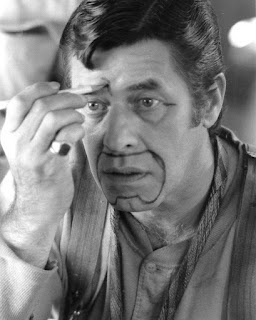

Jerry Lewis plays The Nutty Professor as a lovable loser who gets so lost in his own head that he drones on obliviously. Some of the funniest scenes don’t involve Kelp croaking and yelping, but him rambling on about modern music, or about why he failed to put his glasses in his locker. (“I would’ve put them there myself if I’d known there was a restriction. Some people use them for a façade, I use them for eyes.”) With alter-ego Buddy Love, mostly Lewis is spoofing the kind of macho man sold by the advertising industry, exposing the thin line between arousing the opposite sex and becoming a total creep. There was no love lost between Jerry Lewis and the Rat Pack. It is in the scene at the prom the real Jerry Lewis most clearly emerges—he must step out of character and speak directly to his audience. No matter how that audience reacts, it is Jerry Lewis the man to whom they are directly reacting. And when we see that Buddy Love is a lonely, pitiful man who feels trapped by his audience, by his act, we see how Jerry Lewis sees himself. The Nutty Professor isn’t the only film in which Lewis delves into the schisms within his own psyche, but it was his personal favorite. Source: brightlightsfilm.com

People With Creative Personalities Really Do See the World Differently—What is it about a creative work that elicits our awe and admiration? Is it the thrill of being shown something new, something different, something the artist saw that we did not? The idea that some people see more possibilities than others is central to the concept of creativity. Psychologists often measure creativity using divergent thinking tasks. The aspect of our personality that appears to drive our creativity is called openness to experience. Among the five major personality traits, it is openness that best predicts performance on divergent thinking tasks. Openness also predicts real-world creative achievements, as well as engagement in everyday creative pursuits.

As Scott Barry Kaufman and Carolyn Gregoire explain in their book Wired to Create, the creativity of open people stems from a ‘drive for cognitive exploration of one’s inner and outer worlds’. This curiosity to examine things from all angles may lead people high in openness to see more than the average person, or as another research team put it, to discover ‘complex possibilities laying dormant in so-called “familiar environments”. Another well-known perceptual phenomenon is called “inattentional blindness.” People experience this when they are so focused on one thing that they completely fail to see something else right before their eyes. In our research, published in the Journal of Research in Personality, we found that open people don’t just bring a different perspective to things, they genuinely see things differently to the average individual. Source: www.psychreg.org

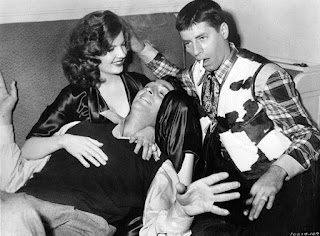

The Stooge (1951) is in many ways a mirror of Dean & Jerry's own rise to fame and also a precursor of the demise of their partnership in 1956. Ted Rogers (Jerry Lewis) is no professional clown. He's funny because he's a dimwit, but also because of a natural ability and, most importantly, because he has a pure heart. Like his character in The Patsy (1964), Ted magically ad-libs a polished routine complete with costumes and props. Also great are Lewis's scenes with a wide-eyed admirer, freckle-faced Genevieve Tait, played with great charm by Marion Marshall. By acting like a little boy in 1952, Jerry was exactly in tune with the Baby Boom generation, and his audience identified with him as a peer. But Jerry could only accept legitimacy in the terms of an earlier culture, one in which such values as “sadness and gracious humility” still held currency.

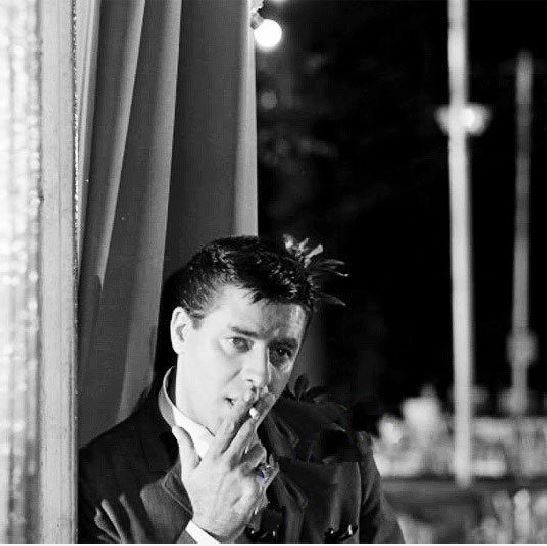

That in his private life he tried as much as possible to comport himself like an up-to-date adult only further revealed the split he felt between himself and the world around him. Even though he was adored, highly compensated and kowtowed, he felt as if the only time in which he wanted to be loved—his childhood—had passed him by. Jerry Lewis was no street urchin, but he had lacked many of the little luxuries most of the kids in his working-class neighborhood had—a rocking horse, a bike, new school clothes each fall. His parents Danny and Rae had moved into a hotel in Times Square, further proof that they saw themselves more as show people than parents and never owned their own home; they rented apartments until Jerry bought them a house in the late 1940s. Jerry couldn’t hide his pain when recalling his family’s modest financial condition: “They were poor and couldn’t help leaving me alone. But I’m supersensitive, and it killed me.” This was a couple, it seems, that just did not care for children; and they had little apparent concern for his comfort, happiness, or security.

When he was old enough to choose a path for himself, he turned to show business as a way of creating a family for himself. Though Jerry wasn’t an orphan, he was often made to feel like one, and in his on-again-off-again relationship with his parents can be found the origins of his thin skin, his eager manner, and his quickness to tears or anger. Many people have survived worse childhoods with less obvious scars, but Jerry came out of his with all these. His bizarre early relationships with women would also take its toll on his already messy demeanor. He had allegedly lost his virginity at age 12 to a stripper named Trudine who lured him into her dressing-room. “She was a piece of work. She danced with a snake,” he remembered. During his Christmas vacation of 1938–39, he met one of his biggest crushes at the Arthur Hotel in Lakewood, New Jersey, a resort forty miles south of Newark. Charlie and Lillian Brown worked as managers in the resort and included Jerry as another member of their family. In later life Jerry remained exceedingly loyal to the Browns, always referring to them as Aunt and Uncle, playing engagements at Arthur Hotel when he could have commanded much more lucrative work.

One of the definitive ruptures between him and Dean Martin, in fact, would be instigated by his loyalty to the Brown family. A large part of Jerry’s affection for the Browns was devoted to their daughter, Lonnie. Like her parents, she sensed the despair that plagued Jerry. A shy, bookish girl, she took Jerry under her wing. He had a crush on her, and he followed her around the hotel and the town of Lakewood like a puppy dog. Lonnie saw how Jerry behaved around his parents, and she was sensitive to the pain her younger friend was suffering. She began to let him into her private world, an entrée that would soon have a monumental impact on his life. There was a clear dychotomy between Trudine and Lonnie, total opposites of female conduct, which would inevitable wreak havoc in his mind and would warrant the genuine awkwardness of his interacions with women onscreen.

During the shoot of My Friend Irma Goes West (1950), Corinne Calvet recalled in her autobiography: “I found Dean friendly, a man of the world, self-assured and quiet. Lewis was exactly the opposite, nervous and trying to override his shyness by flattering and entertaining everyone around him. He seemed to be afraid of silence, to feel compelled to fill the empty spaces. I was sensitive to his great anxiety, his wanting to be liked by everyone.” In the film’s finale, Yvonne Yvonne (Calvet) fell for Seymour (Lewis) and ended up in a romantic clinch with him. In January 1961, Jerry panicked when he learned he stood to be named in a divorce suit being filed by a Southern California restaurateur against his starlet wife, who wanted to collect on her soon-to-be-ex-husband’s estate. Jerry, according to Judith Campbell, who was working for him at the time, “ranted and raved. He would be ruined, his wife Patti would divorce him, his audience would desert him, his friends would hold him in contempt.” Judith Campbell, mistress to both Sam Giancana and John Kennedy, wasn’t at all impressed with Jerry and she found him perfectly resistible: “He quickly goes overboard,” she said. “You expect him to start speaking French. Although he is very serious about his flirting, from a woman’s viewpoint it is funnier than his pratfalls.”

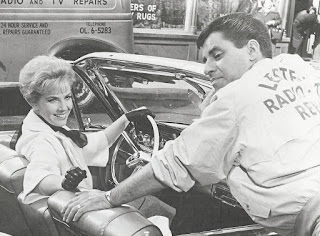

In the early 1950s Martin and Lewis had been a moneymaking machine, it turned out, for everyone except Martin and Lewis. “Plenty of pockets were getting filled,” Jerry remembered, “but there was a big mysterious hole in our own.” Outwardly it looked swell, but it was a dicey existence. “There I was,” Jerry recalled, “driving around in a Cadillac, living in a movie star’s home, and sometimes I didn’t have enough money to pay the grocery bills.” After leaving his home studio, Paramount, most of his solo films tanked or were poorly distributed. American critics—most of whom hadn’t liked his early films—were merciless toward his later ones. (The dim, imperious Bosley Crowther, the longtime chief critic of the New York Times, was reliably harsh.) He was buoyed by the French adoration, but instead of taking that as a reflection of Lewis’s genius, most Americans took that as a sign that the French were nuts.

Jerry Lewis was convinced that too many modern comedians aped previous artists but his opinion was that “imitators never get anywhere,” and “at heart I really belong to the old school which believed that screen comedy is essentially a combination of situation, sadness, and gracious humility.” Murray Pomerance, in his essay Enfant Terrible!: Jerry Lewis in American Film (2002) wrote: "What we really laughted at in Jerry Lewis' films was not the otherness of the suffering but the sameness to our own." “I like good entertainment, nothin’ sordid,” Lewis told Peter Bogdanovich. Asked by Bogdanovich what advice he’d give to young people, Lewis said, “Reach for the child within. The child has never died within you, you’ve just abandoned him, that’s all. Dig him out. Give him some wings and some air and you’ll fly with him.” —"King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis" (1997) by Shawn Levy

Jerry Lewis was convinced that too many modern comedians aped previous artists but his opinion was that “imitators never get anywhere,” and “at heart I really belong to the old school which believed that screen comedy is essentially a combination of situation, sadness, and gracious humility.” Murray Pomerance, in his essay Enfant Terrible!: Jerry Lewis in American Film (2002) wrote: "What we really laughted at in Jerry Lewis' films was not the otherness of the suffering but the sameness to our own." “I like good entertainment, nothin’ sordid,” Lewis told Peter Bogdanovich. Asked by Bogdanovich what advice he’d give to young people, Lewis said, “Reach for the child within. The child has never died within you, you’ve just abandoned him, that’s all. Dig him out. Give him some wings and some air and you’ll fly with him.” —"King of Comedy: The Life and Art of Jerry Lewis" (1997) by Shawn Levy