Sunday, June 01, 2014

A fall from grace: Franchot Tone & Barbara Payton (She wasn't Ashamed)

Franchot Video ("My love for you") video.

Barbara Stanwyck saw what was happening with Joan Crawford’s marriage to Franchot Tone, and though Joan had been changed by Franchot (Joan had hoped their marriage would be like that of the Lunts, joined onstage and off—longtime, loving friends and actors), she was already wearying of him and their endless arguments, in which Tone occasionally, in a drunken rage, beat her, and she would go to work wearing dark glasses to hide the bruises on her face.

Joan and Franchot had finished making The Bride Wore Red, and Joan was working on a picture with Spencer Tracy. Barbara [Stanwyck] knew that Joan was mixed up with Tracy. What Joan was doing with her marriage infuriated Barbara. It was only a flurry with Tracy, but Joan would come home after being with him and call people at two or three in the morning asking if Franchot was there. “Well, I don’t know where he is. He’s out... and I can’t find him. And I’m desperate.” Franchot was out drinking and, said Barbara [Stanwyck], “wearing his heart on his sleeve and staying in some lousy bar” because he’d found out “about Joan and Tracy.”

In addition to Robert Montgomery, the negotiating committee for the Screen Actors Guild consisted of Kenneth Thomson, the guild’s executive secretary and veteran actor from the mid-1920s who appeared in more than sixty pictures; and Franchot Tone, scion of an industrialist fortune, who’d fled his privileged upbringing for the stage to become the handsome, genteel leading man of the Group Theatre. Tone decided to leave the stage for a year when an offer came from Hollywood; the other Group Theatre founders were heartbroken to see him go; they believed Tone had the makings of a great stage actor. Twenty pictures later and with a long-term contract with Metro, Tone was married to one of the studio’s most glamorous stars and had himself become the ultimate of urbane movie idols. Tone, ever ambivalent in his choices, saw his defection from the stage as a fall from grace.

Barbara Payton: "I was engaged to the actor with the most class in Hollywood-Franchot Tone. In other words I was the queen bee, the nuts and boiling hot. The odds were a million to one I'd grow old with twenty servants, three swimming pools and a personal masseuse plus an adoring husband. I try to think of what was my biggest moment-my biggest thrill. I think it was 1950 on St. Valentine's Day. I was going to start a big movie with Jimmy Cagney the next day and I went with Franchot Tone to the opera. I wore a mink stole he had given me and I was dripping ice (diamonds). We marched into the Opera House and it was like everyone had suddenly been struck silent. People stopped whatever they were doing and just stared at us. We were the most glamorous thing since Lily St. Cyr's pasties. Franchot and me, we just stood there and let them gape for a moment. It was heaven."

"Franchot Tone, suave, likeable, quiet, unexciting Franchot asked me to do a play with him in New York. He was hooked on me. He spelled it out for me and I read him... 'Kiss me and your troubles are over.' I may not look like I used to but, not very long ago Franchot Tone asked me again if I'd marry him. You know what he said? 'If you'll marry me, I'll become young for you again. I'll become a boy again.' After living a full life he wanted me back again."

"I was good to Franchot. He was good to me, too. You'd think that combo would strike oil-but it was a dry well." Tom kept zinging Franchot with, 'What the hell, you're twenty years older than Barbara. She's a passionate broad. What happens ten years from now? Are you going to be able to satisfy her?' Franchot kept debating the subject politely but I know he was getting madder and madder and madder. ------A next-door neighbor of Barbara’s named Judson O’Donnell claimed to have witnessed the fight, he said that Tom Neal pummeled Franchot over thirty times, adding, “It was like watching a butcher slaughtering a steer. At first, I thought my refrigerator was on the fritz. It sounded like a prizefighter in a gym beating the bag. It was one of the bloodiest fights I’ve ever seen, and I’ve seen plenty — on that very lawn!” Los Angeles Herald-Examiner staff writer James Bacon reported that he visited Franchot the morning after his plastic surgery. “He was wrapped in enough bandages to fill a Johnson and Johnson warehouse,” said Bacon. “I was told that his face underneath looked like a piece of beefsteak that had been run over by a truck.”------

Barbara Payton: "I loved Tom. I liked and respected Franchot. In May of 1951, I married Franchot Tone, a millionaire success who loved me more than any girl in the world. Sounds like a happy ending to a fairy tale, doesn't it? Sorry - it was just the beginning. Franchot is a lovable, honest, irascible, masochistic man who loves beauty for beauty's sake. Some core of insecurity makes him insanely jealous. He tortured himself. I was only somebody for his doubts, fears, recriminations to bounce off. I resolved to let him spend himself of the torture. It was endless. It built and there was no end in sight. After days of wrangling and reconciliations our attorneys agreed on a settlement."

One of Tom’s more understated (and ludicrous) quotes to the press during this time alluded to his and Barbara’s wedding plans, now canceled. “I’m not paying for her Wassermann if she’s going to continue to see Tone,” he declared with an almost laughable sincerity. With very little effort, Tom’s artless offerings became fodder for a ravenous press intent on crucifying him. Barbara’s friend Tina Ballard offers, “I think Barbara wished she could combine Franchot’s qualities of wealth, intelligence and class with Tom’s down-and-dirty, raw sexuality, and make a whole other person out of them!"

In an example of Hollywood’s growing vendetta against Barbara for the humiliation she had brought to the well-liked Franchot Tone, as well as to the film community in general, Dore Schary, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s Chief of Production, and Darryl F. Zanuck, Vice President of 20th Century-Fox, both of whom had once publicly expressed an interest in buying Barbara’s contract from WB, quickly changed their minds.

Sources: "Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye - The Barbara Payton Story" (2013) by John O'Dowd, "I Am Not Ashamed" (1962) by Barbara Payton, and "A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907-1940" by Victoria Wilson

Barbara Payton, nominated 'the girl most of men would like to be trapped with in an ice-manufacturing plant' about to star in her first major production "Trapped" (1949)

"The Song is You" (2007) by Megan Abbott (Excerpts):

Hop felt funny. She was lonely and he was willing to spare a

minute. “Barbara?”

“Yeah?”

“Let me ask you: you’ve been around this dirty town a few years. You’ve never been afraid to dig your heels in.”

“Hell no.”

“You ever run into Marv Sutton and Gene Merrel out on the town?”

“Yeah.” She paused, which she’d never done once since Hop met her.

“What’s their story?”

“Fuck if I know, Hop.”

“C’mon, Barbara. Between you and me. You don’t need to pussyfoot with me.”

There was another pause. Then, “Look, I don’t like repeating what I ain’t seen firsthand.”

“I’m a clam, Barbara. It’s my one and only virtue.”

“Well, that Marv’s cuddled up to me a few times, but there was something about both of them that rubbed me the wrong way. A girl gets a kind of radar.”

Barbara Payton, circa 1950

So he said now, pointedly, to Barbara Payton, bleached-brittle hair and toreador pants, smell of bar vibrating off her, “You’re the last person, Barbara, that I’d expect to take stock in rumors.” “Hey, I got nothing to hide,” she said, crossing her legs, lipstick-red mule hanging from her twitching foot. “They’re probably all true, every last one. Did you see the photos Mr. Franchot Tone spread all over town a few years back? Those private dick shots of me on my knees, all black garters and beads, before my beloved boxing partner, Tom Neal? How many girls get out of that?”

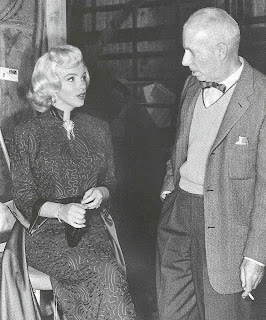

Franchot Tone and Barbara Payton outside the Mocambo nightclub on July 8, 1951 in Los Angeles, California

Hop nodded his signature knowing, understanding nod. She sighed, rubbing her arm wistfully. “What was I supposed to do? Play the blessed virgin or Betty Crocker? I was having a ball. And I wasn’t about to pull the brakes for Louella Parsons or Daryl Zanuck. I know it’s hurt me. I’ve paid. You don’t see me on-screen with Gregory Peck or Jimmy Cagney these days. The money ran out. There were some bad men. I hit the sauce. A bottle of Seconal a hotel doctor had to suck back out of me with a tube. Then I took the route, as the junkies say. It started sticking to me. You know the song. You could sing it to me.” -"The Song is You" (2008) by Megan Abbott

Happy Anniversary, Marilyn Monroe! (new biography by Carl Rollyson)

When Marilyn remained focused, she created an extraordinary range of performances: from the introvert in Bus Stop to the extrovert in The Prince and the Showgirl. Watch just those two films, and you will see why she is a great actress. Each performance is a de novo creation built through a vocabulary of gesture and movement that is inimitable. In her major roles, Marilyn Monroe did not repeat herself.

Primarily because of the skirt-blowing scene, she was treated as having shown more of herself than ever before. The filming of this celebrated scene at 2:30 a.m. on September 10, 1954, in New York City, attracted a crowd variously estimated to have been between one thousand and four thousand people, who watched Monroe’s skirt fly up fifteen times as the scene was rehearsed. DiMaggio had arrived two days earlier and drew the attention of some fans and the press. Amid shouts of “higher” and “hurrah” as the wind-blowing machine puffed his wife’s skirt over her head, DiMaggio retreated in silent anger.

Monroe herself seemed taken aback at the spectacle Billy Wilder had made of her. She is reported to have asked him if he was going to show the more lurid shots to his male cronies. Around 4:00 a.m., Monroe returned to her hotel room. DiMaggio arrived somewhat later. Evidently they quarreled over her night’s work, for “some shouting and scuffling was overheard by other hotel residents nearby, followed by hysterical weeping.” The next day DiMaggio departed for California, and Monroe remained heavily sedated.

When she arrived on the set of The Seven Year Itch, her bruises had to be covered with makeup. Given Monroe’s superb command of Hollywood publicity, it came as a shock a few months later when she announced that she was leaving Twentieth Century-Fox and moving to New York. Almost immediately, however, her move was suspected to be a publicity ploy, and few people seemed to appreciate that she had become so saturated with her own stardom that she felt stymied. Although Monroe would indulge in various kinds of publicity maneuvers for the rest of her career, never again would her life be quite as public as it has been during The Seven Year Itch and her divorce from DiMaggio.

Marilyn celebrating her birthday, 1962 1st June, on the set of Something’s Gotta Give

By the time Something’s Got to Give went into full production on April 23, 1962, the actress was facing a lifetime of failed enthusiasms. Although both Dr. Greenson and Mrs. Murray (acting now as the actress’s housekeeper) believed she was making significant progress, she felt profoundly ambivalent about going back to work. She had not been able to cope well with her buried paranoia, feelings of persecution, frustration, and rage. Before the shooting date, she consulted Nunnally Johnson, who was writing the script, a remake of a 1940 comedy, My Favorite Wife, starring Cary Grant and Irene Dunne.

Johnson had worked on How to Marry a Millionaire and We’re Not Married. Her first words to him, “Have you been trapped into this too?” were a fair indication of her distrust of the studio and of her suspicion of any project it might propose. When Cukor began to revise the script, his actions were tantamount to challenging Monroe’s hard won convictions, for this was a script she could believe in.

The revisions were an attack upon her—especially since, according to Johnson, Cukor had similarly sabotaged her performance in Let’s Make Love. And the studio wanted to get a picture out of Monroe as soon as possible, figuring that her reign as sex symbol was about to expire. Walter Bernstein, the last of six writers to work on Something’s Got To Give, recalls that the studio catered to Monroe’s every whim. Once her artistic vision of the film was violated, she reacted like a politician or a general, making sure her power remained intact. “Sometimes she would refer to herself in the third person, like Caesar. ‘Remember you’ve got Marilyn Monroe,’ she said to Bernstein when she wanted to wear a bikini in one scene. Such comments reveal how difficult it was for the actress to jettison her screen personality. -"Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress (Revised and Updated)" (2014) by Carl Rollyson

Primarily because of the skirt-blowing scene, she was treated as having shown more of herself than ever before. The filming of this celebrated scene at 2:30 a.m. on September 10, 1954, in New York City, attracted a crowd variously estimated to have been between one thousand and four thousand people, who watched Monroe’s skirt fly up fifteen times as the scene was rehearsed. DiMaggio had arrived two days earlier and drew the attention of some fans and the press. Amid shouts of “higher” and “hurrah” as the wind-blowing machine puffed his wife’s skirt over her head, DiMaggio retreated in silent anger.

Monroe herself seemed taken aback at the spectacle Billy Wilder had made of her. She is reported to have asked him if he was going to show the more lurid shots to his male cronies. Around 4:00 a.m., Monroe returned to her hotel room. DiMaggio arrived somewhat later. Evidently they quarreled over her night’s work, for “some shouting and scuffling was overheard by other hotel residents nearby, followed by hysterical weeping.” The next day DiMaggio departed for California, and Monroe remained heavily sedated.

When she arrived on the set of The Seven Year Itch, her bruises had to be covered with makeup. Given Monroe’s superb command of Hollywood publicity, it came as a shock a few months later when she announced that she was leaving Twentieth Century-Fox and moving to New York. Almost immediately, however, her move was suspected to be a publicity ploy, and few people seemed to appreciate that she had become so saturated with her own stardom that she felt stymied. Although Monroe would indulge in various kinds of publicity maneuvers for the rest of her career, never again would her life be quite as public as it has been during The Seven Year Itch and her divorce from DiMaggio.

Marilyn celebrating her birthday, 1962 1st June, on the set of Something’s Gotta Give

By the time Something’s Got to Give went into full production on April 23, 1962, the actress was facing a lifetime of failed enthusiasms. Although both Dr. Greenson and Mrs. Murray (acting now as the actress’s housekeeper) believed she was making significant progress, she felt profoundly ambivalent about going back to work. She had not been able to cope well with her buried paranoia, feelings of persecution, frustration, and rage. Before the shooting date, she consulted Nunnally Johnson, who was writing the script, a remake of a 1940 comedy, My Favorite Wife, starring Cary Grant and Irene Dunne.

Johnson had worked on How to Marry a Millionaire and We’re Not Married. Her first words to him, “Have you been trapped into this too?” were a fair indication of her distrust of the studio and of her suspicion of any project it might propose. When Cukor began to revise the script, his actions were tantamount to challenging Monroe’s hard won convictions, for this was a script she could believe in.

The revisions were an attack upon her—especially since, according to Johnson, Cukor had similarly sabotaged her performance in Let’s Make Love. And the studio wanted to get a picture out of Monroe as soon as possible, figuring that her reign as sex symbol was about to expire. Walter Bernstein, the last of six writers to work on Something’s Got To Give, recalls that the studio catered to Monroe’s every whim. Once her artistic vision of the film was violated, she reacted like a politician or a general, making sure her power remained intact. “Sometimes she would refer to herself in the third person, like Caesar. ‘Remember you’ve got Marilyn Monroe,’ she said to Bernstein when she wanted to wear a bikini in one scene. Such comments reveal how difficult it was for the actress to jettison her screen personality. -"Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress (Revised and Updated)" (2014) by Carl Rollyson

Friday, May 30, 2014

Happy Anniversary, Howard Hawks! Marilyn Monroe: Another World's Blonde

Marilyn Monroe - 'Monkey Business' Premiere (Rare footage). "Monkey Business" (1952) is a screwball comedy film directed by Howard Hawks and starring Cary Grant, Ginger Rogers, Charles Coburn, Marilyn Monroe, and Hugh Marlowe. To avoid confusion with the famous Marx Brothers movie of the same name, this film is sometimes referred to as Howard Hawks' Monkey Business.

Marilyn seemed at ease on screen in the comedy 'Monkey Business,' her third movie of 1952, but did not get on with the director, Howard Hawks. Physically impressive (like Huston) Hawks was “six-feet-three, broad shouldered, slim-hipped, soft-spoken, confident in manner, conservative in dress, and utterly distinguished overall.” Born in Indiana, the son of a wealthy paper manufacturer, Hawks was educated at Exeter and graduated from Cornell in 1917 with a degree in mechanical engineering. He was a lieutenant in the Army Air Corps in World War I, and after the war built airplanes and a racing car that won the Indianapolis 500.

In 1922 he came to Hollywood, where screenwriter Niven Busch found him impressively distant and formidably frigid: “He gave me his reptilian glare. The man had ice-cold blue eyes and the coldest of manners. He was like that with everyone – women, men, whatever. He was remote; he came from outer space. He wore beautiful clothes. He spoke slowly in a deep voice. He looked at you with these frozen eyes.” Marilyn has the decorative but unrewarding role of Charles Coburn’s secretary. In one scene the seventy-five-year-old Coburn “had to chase and squirt Marilyn with a siphon of soda, a moment he approached with glee. Any seeming reluctance, he later explained,was only his indecision about where on Marilyn’s... um... ample proportions to squirt the soda.”

Despite her small part, Marilyn also caused trouble on this picture and forced Hawks to shoot around her when she failed to show up. The problem, as everyone later discovered, was her infected appendix, which she had removed, in late April 1952, as soon as her work was completed. No doctor performing an appendectomy would excise her reproductive organs. The formidable Hawks, mistaking her pain and fear for stupidity, was even more critical than Fritz Lang. Hawks considered Marilyn ‘so goddamn dumb’ that she was wary and afraid of him.

Still, Hawks admitted that she did a fine job in the film and that ‘the camera liked her.’ Cary Grant, like Celeste Holm and many other colleagues, was surprised by her meteoric rise to fame the following year: “I had no idea she would become a big star. If she had something different from any other actress, it wasn’t apparent at the time. She seemed very shy and quiet. There was something sad about her.” To the other actors Marilyn could seem ordinary, unresponsive and apparently “dumb,” but on camera she seemed to glow.

By 1953, against almost impossible odds, Marilyn had achieved the stardom she longed for. Yet her celebrity intensified her insecurity and unhappiness. The novelist Daphne Merkin wrote that Marilyn’s “desperation was implacable in the face of fame, fortune and the love of celebrated men. . . There is never sufficient explanation for the commotion of her soul” – though the reasons can, in fact, be found. Her wretched background, together with the pressures of life as a movie star, created her mental and emotional chaos. The cinematographer Jack Cardiff described it as “an aura of blank remoteness, of being in another world.”

As Howard Hawks remarked, “there wasn’t a real thing about her. Everything was completely unreal.” In Marilyn’s last two films of 1953 she played her typical and most popular incarnation: the gold-digger with a heart of gold. In 'Gentlemen Prefer Blondes' – based on the book and musical comedy by Anita Loos and directed by Howard Hawks – a dumb blonde and a showgirl, both well endowed, sail to Paris to find rich husbands.

In one scene of 'Gentlemen Prefer Blondes' Marilyn wears a top hat, long black gloves, transparent black stockings, high heels and a gaudy sequined costume cut like a bathing suit. In another, wearing a strapless, floor-length, pink satin gown, with long-sleeved gloves, she steals the show by singing “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend.” The best lines in the film – “Those girls couldn’t drown. Something about them tells me they couldn’t sink” – were cut by the censor.

'Gentlemen Prefer Blondes' had been a 1925 book by the fabulous Anita Loos, which spawned a long-running Broadway adaptation. Hawks was ostensibly making a film version of the play, but the play didn’t have much of a workable plot, so he was rewriting it extensively with Charles Lederer, and the rewrite entailed discarding a fair number of the famous songs from the stage version—a decision which somewhat calls into question the logic of making a movie version of the show in the first place. And if the whole point of the thing seemed to be a justification for 90 minutes worth of breast jokes, Hawks seemed blithely unaware of the sex appeal of his two stars. In one of the strangest things anyone has ever said, Hawks said of Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell “I never thought of either of them as having any sex.” They just weren’t his type.

Marilyn made a freeflowing tape for her psychiatrist, with “extensive comments about her problems achieving orgasm – in very blunt language.” Emphasizing the crucial paradox in her life, she bitterly said, “I just don’t get out of sex what I hear other women do. Maybe I’m a sexless sex goddess.” It’s sadly ironic that Marilyn herself did not live to see the sexual revolution and suffered greatly for being its symbol. She’d experienced intense sexual pleasure with Jim Dougherty and with Fred Karger in the mid-1940s; but by the 1950s, under the stress of promiscuous sex and stardom, she’d become frigid.

The photographer André de Dienes said that “Marilyn is not sexy at all. She has very little feeling toward sex. She is not sensuous.” The make-up man George Masters frankly called her “an ice-cold cookie, as frigid as forty below zero, and about as passionate as a calculating machine.” The costume designer Billy Travilla, who knew her in the early 1950s, was more sympathetic and felt the need to protect her, but was also disappointed by her inability to respond: “Her lips would tremble. Those lips! And a man can’t fight it. You don’t want that baby to cry. I think she wanted to love, but she could only love herself. She was totally narcissistic.” -"The Genius and the Goddess: Arthur Miller & Marilyn Monroe" (2009) by Jeffrey Meyers

Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Splitsville: Franchot Tone & Barbara Payton, Mad Men 'Waterloo' (Don & Megan)

Born February 27, 1905, in Niagara Falls, New York, Franchot Tone excelled in playing the debonair, tuxedo-suited aristocrat in his many film roles, which included an Academy Award-nominated performance in the classic 1935 picture 'Mutiny on the Bounty.' By 1950, he had nearly 60 films to his credit and was one of the town’s wealthiest and most respected stars. Los Angeles Magazine writer Tom Johnson offers a description of the actor: “Franchot Tone: a dapper man-about-town, the kind of guy who could make lighting a cigarette look like mankind’s highest calling. He was safe, secure, successful, dignified, and everything a woman could ask for.”

In 1933 Tone had completed seven motion pictures for MGM, co-starring with his future wife, Joan Crawford, for the first time, in Howard Hawks’ popular World War I drama, 'Today We Live'. One of his finest enactments of his near patented, rich playboy characterization was in 'Dancing Lady,' in which he and Clark Gable were rivals for Crawford’s affections. He was paired with Crawford for a third time in 'Sadie McKee' (1934), before being loaned to Paramount for 'The Lives of a Bengal Lancer.'

Bob Thomas writes (about Tone's courtship of Joan Crawford): “He was charmingly insistent, lavishing on her not only flowers but also rare books and works of art. At night he built a fire in her den and read Ibsen, Shaw and Shakespeare to her while she hooked a rug.” Rumors of Franchot’s intense professional jealousy and alleged heavy drinking, physical arguments, and rampant unfaithfulness on both their parts culminated with the couple’s divorce in April 1939.

After a staggering 29 motion pictures in six years, Franchot left MGM after 'Fast and Furious' (1939), a Busby Berkeley directed mystery/comedy, co-starring Ann Sothern. He returned to the New York stage, and to the Group Theater, to co-star with Sylvia Sidney in The Gentle People, a fine production that nonetheless flopped. Often relegated to second male leads for the remainder of his film career, Tone never quite managed to break out of the narrow mold Hollywood had cast him in. “Franchot Tone is a gentleman by breeding and inclination,” Burgess Meredith told TV Guide in January 1966. "He’s always been a man’s man, a hunter, a fisherman, and also a woman’s man. He’s an intellect, a man of charm, good looks, perception and enormous natural gifts as an actor."

In 1941, Franchot, 36, married 18-year-old, ex-Earl Carroll showgirl and Paramount starlet Jean Wallace (Blaze of Noon), and the couple eventually had two sons, Pascal Franchot and Thomas Jefferson Tone. However, this marriage, too, proved stormy and problematic, and would not endure. The blonde-haired Wallace, whose facial appearance and provocative figure bore striking similarities to Barbara Payton’s, would later go up against her lookalike nemesis in a highly-publicized court case. She also appeared to share Barbara’s propensity for trouble.

By 1948, Jean’s frequent domestic squabbles with Franchot led to an acrimonious breakup that found them wrangling over custody of their sons. During their divorce trial, Franchot accused his wife of committing adultery with several men, including Johnny Stompanato, who later would gain posthumous notoriety when he was stabbed to death by 14-year-old Cheryl Crane (the daughter of his lover, Lana Turner).

The suave, tuxedoed Franchot Tone twittered on Barbara's every word the night they met in Ciro's. "She was a sparkling liquid tipping at the brim," Tone recalled, "Radiating beauty like a phosphorous doll..." Carrying scars from a corrosive, second divorce -to actress Jean Wallace- Tone found the young Barbara "vampy and outrageously appealing".

Franchot was still walking around in a kind of daze over Barbara and continued to court her with almost daily gifts of champagne, flowers and expensive jewelry. Barbara responded by lovingly nicknaming him “Doc” and treated him to delicious, home-cooked meals at her Hollywood Boulevard apartment. “Franchot Tone was a very nice and extremely generous person,” adds Jan Redfield (Barbara's sister-in-law). “We saw him several times at Barbara’s apartment and he was a lovely man. Although I don’t think I ever saw him without a drink in his hand, he was never out of line nor did I ever hear him raise his voice at Barbara ever. His manners were always impeccable. I think Barbara saw him as someone who would love her unconditionally and take care of her and support her — things she didn’t always get from her father.”

According to Lisa Burks: "Franchot was extremely altruistic and I think he tried to give the relationship every chance, but he could not endure the humiliation of Tom’s constant presence in Barbara’s life before he gave up. Her continued infidelity with Tom Neal aside, I think Franchot finally gave up on Barbara when she, in a way, began to give up on herself." According to Barbara's autobiography "I'm Not Ashamed", Franchot offered to marry her again, attempting to rescue Barbara from her self-destruction, promising her "I'll be young for you again." Sadly, Barbara was too far gone by then. -"Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye - The Barbara Payton Story" (2013) by John O'Dowd

Don clearly didn't see his split from Megan coming, but once he realizes the sad truth that Megan can't bring herself to say, he doesn't handle it with the bile he once spewed at Betty; instead, he promises Megan all of the resources he can offer and allows their marriage to come to a quiet end. Later, he makes a professional sacrifice when he tells Peggy to deliver the Burger Chef pitch, voluntarily giving up his last chance to make himself irreplaceable at Sterling Cooper so he can give his protégé the chance she earned. Source: theweek.com

Don makes a call to Megan and, by doing so, severs his own tie — to love, to California, to the promise of rebirth and manifest destiny. He confesses to her that he’s about to be fired, that he thought if he kept his head down and did his job, things would work out. He offers to go to Los Angeles, and Megan just doesn’t say anything, leaning on her beautiful green phone. She’s done. Maybe they’re done forever and ever and it’s time for a trip to Reno. Source: flavorwire.com

In 1933 Tone had completed seven motion pictures for MGM, co-starring with his future wife, Joan Crawford, for the first time, in Howard Hawks’ popular World War I drama, 'Today We Live'. One of his finest enactments of his near patented, rich playboy characterization was in 'Dancing Lady,' in which he and Clark Gable were rivals for Crawford’s affections. He was paired with Crawford for a third time in 'Sadie McKee' (1934), before being loaned to Paramount for 'The Lives of a Bengal Lancer.'

Bob Thomas writes (about Tone's courtship of Joan Crawford): “He was charmingly insistent, lavishing on her not only flowers but also rare books and works of art. At night he built a fire in her den and read Ibsen, Shaw and Shakespeare to her while she hooked a rug.” Rumors of Franchot’s intense professional jealousy and alleged heavy drinking, physical arguments, and rampant unfaithfulness on both their parts culminated with the couple’s divorce in April 1939.

After a staggering 29 motion pictures in six years, Franchot left MGM after 'Fast and Furious' (1939), a Busby Berkeley directed mystery/comedy, co-starring Ann Sothern. He returned to the New York stage, and to the Group Theater, to co-star with Sylvia Sidney in The Gentle People, a fine production that nonetheless flopped. Often relegated to second male leads for the remainder of his film career, Tone never quite managed to break out of the narrow mold Hollywood had cast him in. “Franchot Tone is a gentleman by breeding and inclination,” Burgess Meredith told TV Guide in January 1966. "He’s always been a man’s man, a hunter, a fisherman, and also a woman’s man. He’s an intellect, a man of charm, good looks, perception and enormous natural gifts as an actor."

In 1941, Franchot, 36, married 18-year-old, ex-Earl Carroll showgirl and Paramount starlet Jean Wallace (Blaze of Noon), and the couple eventually had two sons, Pascal Franchot and Thomas Jefferson Tone. However, this marriage, too, proved stormy and problematic, and would not endure. The blonde-haired Wallace, whose facial appearance and provocative figure bore striking similarities to Barbara Payton’s, would later go up against her lookalike nemesis in a highly-publicized court case. She also appeared to share Barbara’s propensity for trouble.

By 1948, Jean’s frequent domestic squabbles with Franchot led to an acrimonious breakup that found them wrangling over custody of their sons. During their divorce trial, Franchot accused his wife of committing adultery with several men, including Johnny Stompanato, who later would gain posthumous notoriety when he was stabbed to death by 14-year-old Cheryl Crane (the daughter of his lover, Lana Turner).

The suave, tuxedoed Franchot Tone twittered on Barbara's every word the night they met in Ciro's. "She was a sparkling liquid tipping at the brim," Tone recalled, "Radiating beauty like a phosphorous doll..." Carrying scars from a corrosive, second divorce -to actress Jean Wallace- Tone found the young Barbara "vampy and outrageously appealing".

Franchot was still walking around in a kind of daze over Barbara and continued to court her with almost daily gifts of champagne, flowers and expensive jewelry. Barbara responded by lovingly nicknaming him “Doc” and treated him to delicious, home-cooked meals at her Hollywood Boulevard apartment. “Franchot Tone was a very nice and extremely generous person,” adds Jan Redfield (Barbara's sister-in-law). “We saw him several times at Barbara’s apartment and he was a lovely man. Although I don’t think I ever saw him without a drink in his hand, he was never out of line nor did I ever hear him raise his voice at Barbara ever. His manners were always impeccable. I think Barbara saw him as someone who would love her unconditionally and take care of her and support her — things she didn’t always get from her father.”

According to Lisa Burks: "Franchot was extremely altruistic and I think he tried to give the relationship every chance, but he could not endure the humiliation of Tom’s constant presence in Barbara’s life before he gave up. Her continued infidelity with Tom Neal aside, I think Franchot finally gave up on Barbara when she, in a way, began to give up on herself." According to Barbara's autobiography "I'm Not Ashamed", Franchot offered to marry her again, attempting to rescue Barbara from her self-destruction, promising her "I'll be young for you again." Sadly, Barbara was too far gone by then. -"Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye - The Barbara Payton Story" (2013) by John O'Dowd

Don clearly didn't see his split from Megan coming, but once he realizes the sad truth that Megan can't bring herself to say, he doesn't handle it with the bile he once spewed at Betty; instead, he promises Megan all of the resources he can offer and allows their marriage to come to a quiet end. Later, he makes a professional sacrifice when he tells Peggy to deliver the Burger Chef pitch, voluntarily giving up his last chance to make himself irreplaceable at Sterling Cooper so he can give his protégé the chance she earned. Source: theweek.com

Don makes a call to Megan and, by doing so, severs his own tie — to love, to California, to the promise of rebirth and manifest destiny. He confesses to her that he’s about to be fired, that he thought if he kept his head down and did his job, things would work out. He offers to go to Los Angeles, and Megan just doesn’t say anything, leaning on her beautiful green phone. She’s done. Maybe they’re done forever and ever and it’s time for a trip to Reno. Source: flavorwire.com

Saturday, May 24, 2014

Franchot Tone: Smooth P.I. in "Love Trouble"

'I Love Trouble' (1948) is a film noir written by Roy Huggins from his first novel 'The Double Take,' directed by S. Sylvan Simon, and starring Franchot Tone as Stuart Bailey. Plot: A wealthy man hires a detective to investigate his wife's past. The detective (Franchot Tone) discovers that the wife had been a dancer and left her home town with an actor. The latter is killed before he can talk, but, with the help of a showgirl, the detective learns that the wife had used stolen papers from a girl friend to enter college after she had stolen $40,000 from the night club where she worked.

Franchot Tone was a terrific actor. He could play a psycho as in "Phantom Lady" and "Man on the Eiffel Tower" or he could switch to a smooth, fast-thinking and highly intelligent private eye as in "I Love Trouble". The title is misleading. It suggests a comedy-mystery, which this is not. Tone is not sardonic, like a Dick Powell. He's not weary, like a Robert Mitchum, and he's not tough, like a Humphrey Bogart. He's smart and quick-witted and self-controlled.

Janet Blair pops up, as the sister of whom this wife had taken an identity before her marriage. And Janet's real sister, the possessor of that identity, has happily left it behind when she married. That's Janis Carter, affecting a terrible South American accent. Tone doesn't know if he can trust Blair, but he knows he's attracted to her. Meanwhile his detecting takes him all over LA and nearby places where he meets up with a bevy of well-known supporting players and complications.

This is noir, done Chandler-style in complexity, in which even the writer may not know who did what to whom, when, and why. I haven't grasped it all myself, but the ride is sure enjoyable, and I'll take it again. It's done in a lighter Dick Powell "Murder My Sweet" vein, but without any narration. Solid film noir.

A great turn by Franchot Tone as LA private eye Stuart ‘George’ Bailey, who out-Bogart’s and out-Powell’s Philip Marlowe in a deliciously convoluted story of deception, greed, frame-ups, murder, and sexy high jinks. Bit player Glenda Farrell is a comic delight as Bailey’s cute, loyal, eccentric, and sharp-as-nails secretary Hazel. Tom Powers delivers a solid performance as the aging suspicious husband who hires Bailey to tail his young wife, who is being blackmailed. Steven Geray delivers a nuanced low-key performance as mysterious crime-boss Keller, and John Ireland, Raymond Burr, and Eddie Marr are great as Keller’s heavies. Sid Tomack is in his element as a small-time chiseller who is out of his league. The dames are all delightfully buxom good-bad girls, with enough charm and innuendo for a dozen Marlowes: Janet Blair, Janis Carter, Adele Jergens, Lynn Merrick, and Claire Carleton. A weird waitress-from-hell played by uncredited bit-player Roseanne Murray, is a scream. Source: filmsnoir.net

One afternoon in the Formosa Café near Goldwyn Studios, the actor Franchot Tone approached Beth Short (The Black Dahlia). She was at the bar as the actor stepped from the inside telephone booth. He pretended to know her, dropping a few names, but Beth only smiled and shook her head. “She said she was waiting for someone,” Tone says, “and I said to her, ‘Of course you are, you’re waiting for me! And I have just arrived.”’ He says it was “a ridiculous line” he had used before. The actor insisted he remembered her “very well... and I think many girls were flattered by it, but this one seemed more concerned that I’d had too much to drink.”

He told her he had finished a film with director Robert Siodmak, 'Phantom Lady,' and convinced Beth that an associate interviewing young women with “your kind of looks” would be most interested in meeting her. He took her to the unoccupied office of the “associate” but she was not interested in cozying up on the sofa, which opened into a bed. Tone says, “I thought it was a pickup from the start but to her it wasn’t anything of the kind!” It was an extraordinary experience, Tone later recalled. Beth believed they had “hit it off” as people. She was disappointed that Tone had only “that” in mind. He tried to kiss her a couple of times and told her she had the most gorgeous eyes in the world, which he thought she did—dreamy eyes that he was almost seeing through grey smoke. He could imagine her as a siren luring sailors to their death. And then she turned ice cold. Always the gentleman, Tone turned the situation around and made it seem that he had made a mistake thinking that she was after romance. He did find her most refreshing to “talk” to, he said, but secretly the actor was flustered —a pathetic scene, and the girl seemed so sad that Tone had to hold back tears. “She told me she’d been ill,” he says, “something about an operation to her chest.” He gave her a phone number to reach him about “the part and the associate. I gave her whatever bills were in my wallet. It was a strange and unsettling experience. Even after I called a cab for her and she was gone, the feeling stayed with me. It was almost as though I had experienced being afraid of her.” -Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder (2006) by by John Gilmore

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Barbara Payton & Franchot Tone: Love Brawl

Today We Live (1933) -- Well here's the answer to the trivia question, "What movie did Joan Crawford and Gary Cooper star in together?" Based on a short story by William Faulkner (who also worked on the screenplay), it's a soapy love triangle set in the English countryside during World War I. Joan plays a lonely young (British) woman who is torn between love of her brash tenant (Gary Cooper) and a valiant soldier (Robert Young). Franchot Tone plays Joan's brother -- two years later the couple were married in real life! -- Turner Classic Movies, Wednesday, 8:15 a.m. Source: www.theeagle.com

In the 1940s, Tone’s film roles varied widely. One moment he was involved in fluffy affairs with the much younger Deanna Durbin (in Nice Girl?, His Butler’s Sister, and Because of Him), the next he was up to his neck in some sort of dangerous business in, say, Billy Wilder’s Five Graves to Cairo, with Erich von Stroheim and Anne Baxter;

Robert Siodmak’s classic film noir Phantom Lady, with Ella Raines. Apparently, it was Joan Harrison, Universal’s first female producer and former screenwriter for Alfred Hitchcock, who brought Phantom Lady to Franchot’s attention. He admired her talent, trusted her instincts, and was eager to learn from her. Also, Franchot loved both working with newcomers (such as co-star Ella Raines) and trying new forms of cinematic expression. Phantom Lady would prove to be Robert Siodmak’s breakthrough film at Universal, and it set the early standard for film noir. But when it came down to it, Franchot was hungry to play a dark role and Jack Marlow fit the bill.

-Franchot Tone was Joan Crawford’s second husband (1935-1939). What was that marriage like? And what was it like for Tone to play opposite Crawford, then one of MGM’s top stars, in no less than seven films?

-Franchot and Joan’s marriage was her second (or third, depending on who you talk to) and his first, and it was a passionate one. They remained friends after their divorce and until Franchot’s death; I think that connection speaks for itself. A true love story even though the marriage didn’t work out.

Franchot loved women. Loved. His sexual appetite was an integral part of his identity. He was most happy when he was married because those relationships gave him stability — except for his short, tumultuous union with [minor leading lady] Barbara Payton [1951-1952]. He also loved family life; he had two sons with his second wife, actress Jean Wallace [1941-1948; Wallace later married Cornel Wilde]. But when he was single, he was never lacking in female companionship. [Tone’s fourth -- and last -- wife was actress Dolores Dorn, 1956-1959.]

-Franchot Tone’s film career came to a halt in the early 1950s. Why?

-That decade got off to a rocky start with his marriage to Barbara Payton, which took a huge toll on him both emotionally and physically. (After the fisticuffs with his romantic rival, boxer/actor Tom Neal). He felt betrayed and publicly humiliated by Payton’s infidelities. But he had to keep going, for his sons and for himself. Source: www.altfg.com

John O'Dowd: Franchot Tone first met Barbara at Ciro's nightclub in Hollywood in 1950, and was evidently blown away by her beauty. She, in turn, was most likely impressed with his millionaire status and with the fact that he was a very big movie star. Tone reportedly wooed her with daily gifts of champagne, flowers, and expensive jewelry, while Barbara reciprocated with home-cooked meals. The couple was soon engaged and was photographed often over the next year at various film premieres and nightclubs. When Tone left on a business trip to NYC in July 1951, Barbara attended a pool party in Hollywood and met Tom Neal.

An inveterate romantic, Barbara was immediately swept off her feet by Neal's rugged good looks and machismo, and quickly broke off her engagement to Tone. Several engagements followed--to both men--and she was all set to walk down the aisle with Neal in September 1951 when, on the eve of their wedding, she dumped him for an afternoon tryst with Tone at The Beverly Hills Hotel. Tom was living with Barbara at the time, and in the wee hours of September 14, he ambushed the couple upon their return to her home. Neal was an ex-amateur boxer and a weightlifter, and he hammered Franchot Tone into the ground. Tone was rushed to the hospital with severe head injuries, and for the next 18 hours he lingered near death in a comatose state. The brawl made worldwide headlines and brought a torrent of bad press raining down on the trio. Tom Neal had a comfortable upbringing in the Chicago suburb of Evanston and there were no police incidents in his youth. It appears that Barbara often toyed with Tom's emotions, as she was often inclined to do with the men in her life. "She drove the men in her life nuts" is how Tom's son put it to me. -John O'Dowd interviewed by writer Alan K. Rode in 'The Big Chat' Source: www.noirfilm.com

“Hop, you have no idea how rough it is,” the actress said, lighting a match off the bottom of her shoe like the slickest of New York bookies. “I know, Barbara. Believe me.” “Here I got one guy in love with me—Franchot—he reads Zigmund Freud to me while my head’s in his lap, and I got another guy, Tom, muscles like poured concrete, who’d just as soon gut Franchot as give up one night with his chin nestled in my thighs. Why make it either/or? Why not both?” Her lips curled into a smirk and he couldn’t help but laugh. She did, too, like a horse. On her it was inexplicably sexy. “I understand, Barbara. I really do. But you got a dozen columnists chasing this story.” She tapped her cigarette on one silky knee. “Fuck, Hop, what do I care? I’m having a ball. It’s not like I compete with Loretta Young for parts. I play hookers, molls, pinup girls.”

Hop hadn’t bothered with Tom Neal, a side of beef in tight pants. But he’d worked Franchot Tone a bit. Over the last week, he’d carried on several soulful late-night conversations with the longfaced, highbrow actor. “What do I care what they say?” Tone had confided. “Don’t you see? I love her. Love that darling girl.” And it was no surprise to Hop. Tone had long had a taste for beauties whose hems were still wet from the gutter. Even Joan Crawford, whom Tone married when she was Hollywood royalty, came with the richly thrilling backstory of a pre-fame gold-standard stag film, a seven-minute loop Hop himself had seen at more than one Hollywood party. It had been shown so many times at so many different gatherings that it had taken on the quality of a ho-hum home movie trotted out one too many Christmas mornings. -"The Song is You: A Novel" (2008) by Megan Abbott

For more details, please read my previous post: The Barbara Payton story

In the 1940s, Tone’s film roles varied widely. One moment he was involved in fluffy affairs with the much younger Deanna Durbin (in Nice Girl?, His Butler’s Sister, and Because of Him), the next he was up to his neck in some sort of dangerous business in, say, Billy Wilder’s Five Graves to Cairo, with Erich von Stroheim and Anne Baxter;

Robert Siodmak’s classic film noir Phantom Lady, with Ella Raines. Apparently, it was Joan Harrison, Universal’s first female producer and former screenwriter for Alfred Hitchcock, who brought Phantom Lady to Franchot’s attention. He admired her talent, trusted her instincts, and was eager to learn from her. Also, Franchot loved both working with newcomers (such as co-star Ella Raines) and trying new forms of cinematic expression. Phantom Lady would prove to be Robert Siodmak’s breakthrough film at Universal, and it set the early standard for film noir. But when it came down to it, Franchot was hungry to play a dark role and Jack Marlow fit the bill.

-Franchot Tone was Joan Crawford’s second husband (1935-1939). What was that marriage like? And what was it like for Tone to play opposite Crawford, then one of MGM’s top stars, in no less than seven films?

-Franchot and Joan’s marriage was her second (or third, depending on who you talk to) and his first, and it was a passionate one. They remained friends after their divorce and until Franchot’s death; I think that connection speaks for itself. A true love story even though the marriage didn’t work out.

Franchot loved women. Loved. His sexual appetite was an integral part of his identity. He was most happy when he was married because those relationships gave him stability — except for his short, tumultuous union with [minor leading lady] Barbara Payton [1951-1952]. He also loved family life; he had two sons with his second wife, actress Jean Wallace [1941-1948; Wallace later married Cornel Wilde]. But when he was single, he was never lacking in female companionship. [Tone’s fourth -- and last -- wife was actress Dolores Dorn, 1956-1959.]

-Franchot Tone’s film career came to a halt in the early 1950s. Why?

-That decade got off to a rocky start with his marriage to Barbara Payton, which took a huge toll on him both emotionally and physically. (After the fisticuffs with his romantic rival, boxer/actor Tom Neal). He felt betrayed and publicly humiliated by Payton’s infidelities. But he had to keep going, for his sons and for himself. Source: www.altfg.com

John O'Dowd: Franchot Tone first met Barbara at Ciro's nightclub in Hollywood in 1950, and was evidently blown away by her beauty. She, in turn, was most likely impressed with his millionaire status and with the fact that he was a very big movie star. Tone reportedly wooed her with daily gifts of champagne, flowers, and expensive jewelry, while Barbara reciprocated with home-cooked meals. The couple was soon engaged and was photographed often over the next year at various film premieres and nightclubs. When Tone left on a business trip to NYC in July 1951, Barbara attended a pool party in Hollywood and met Tom Neal.

An inveterate romantic, Barbara was immediately swept off her feet by Neal's rugged good looks and machismo, and quickly broke off her engagement to Tone. Several engagements followed--to both men--and she was all set to walk down the aisle with Neal in September 1951 when, on the eve of their wedding, she dumped him for an afternoon tryst with Tone at The Beverly Hills Hotel. Tom was living with Barbara at the time, and in the wee hours of September 14, he ambushed the couple upon their return to her home. Neal was an ex-amateur boxer and a weightlifter, and he hammered Franchot Tone into the ground. Tone was rushed to the hospital with severe head injuries, and for the next 18 hours he lingered near death in a comatose state. The brawl made worldwide headlines and brought a torrent of bad press raining down on the trio. Tom Neal had a comfortable upbringing in the Chicago suburb of Evanston and there were no police incidents in his youth. It appears that Barbara often toyed with Tom's emotions, as she was often inclined to do with the men in her life. "She drove the men in her life nuts" is how Tom's son put it to me. -John O'Dowd interviewed by writer Alan K. Rode in 'The Big Chat' Source: www.noirfilm.com

“Hop, you have no idea how rough it is,” the actress said, lighting a match off the bottom of her shoe like the slickest of New York bookies. “I know, Barbara. Believe me.” “Here I got one guy in love with me—Franchot—he reads Zigmund Freud to me while my head’s in his lap, and I got another guy, Tom, muscles like poured concrete, who’d just as soon gut Franchot as give up one night with his chin nestled in my thighs. Why make it either/or? Why not both?” Her lips curled into a smirk and he couldn’t help but laugh. She did, too, like a horse. On her it was inexplicably sexy. “I understand, Barbara. I really do. But you got a dozen columnists chasing this story.” She tapped her cigarette on one silky knee. “Fuck, Hop, what do I care? I’m having a ball. It’s not like I compete with Loretta Young for parts. I play hookers, molls, pinup girls.”

Hop hadn’t bothered with Tom Neal, a side of beef in tight pants. But he’d worked Franchot Tone a bit. Over the last week, he’d carried on several soulful late-night conversations with the longfaced, highbrow actor. “What do I care what they say?” Tone had confided. “Don’t you see? I love her. Love that darling girl.” And it was no surprise to Hop. Tone had long had a taste for beauties whose hems were still wet from the gutter. Even Joan Crawford, whom Tone married when she was Hollywood royalty, came with the richly thrilling backstory of a pre-fame gold-standard stag film, a seven-minute loop Hop himself had seen at more than one Hollywood party. It had been shown so many times at so many different gatherings that it had taken on the quality of a ho-hum home movie trotted out one too many Christmas mornings. -"The Song is You: A Novel" (2008) by Megan Abbott

For more details, please read my previous post: The Barbara Payton story

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

_01.jpg)

_NRFPT_01.jpg)

_06.jpg)

_07.jpg)

_01.jpg)

_12.jpg)

_02.jpg)

_NRFPT_10.jpg)

_10.jpg)

_28.jpg)

_23.jpg)

_1.jpg)

.jpg)