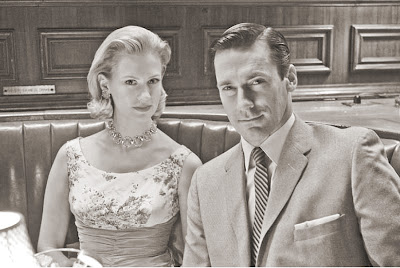

Don Draper (Jon Hamm) and Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss) in "Mad Men" (Season 5, Episode 13 "The Phantom")

Don Draper (Jon Hamm) and Peggy Olson (Elisabeth Moss) in "Mad Men" (Season 5, Episode 13 "The Phantom") "What happens to Peggy after she joins Cutler Gleason and Chaough?" Responding to the first question, creator Matthew Weiner said, "You have to watch." However, the writer made sure that fans will see more of Peggy as he told New York Times, "She's still part of the show. So far. We want to know where she is in this world." He coyly added, "I can't tell you what's planned for her, but there she was." Source: www.aceshowbiz.com

"What happens to Peggy after she joins Cutler Gleason and Chaough?" Responding to the first question, creator Matthew Weiner said, "You have to watch." However, the writer made sure that fans will see more of Peggy as he told New York Times, "She's still part of the show. So far. We want to know where she is in this world." He coyly added, "I can't tell you what's planned for her, but there she was." Source: www.aceshowbiz.com "The Fifties were hypocritical and secretive ... on the surface it was such a happy, lovely time, but it wasn’t like that at all, it was what we pretended, and underneath was exactly what’s happening today : the broken hearts, the looking for love, the lies, the fears." -Jaffe cited in Montagne, 2005. While author Rona Jaffe is here recalling the historical context for her first novel, The Best of Everything, published in 1958, her words have resonance for viewers of Matthew Weiner’s hit show, Mad Men, despite the show’s storyline beginning in 1960. “The Fifties” lasted longer than the decade from 1950 to 1959, and are not bound by those end-dates.

"The Fifties were hypocritical and secretive ... on the surface it was such a happy, lovely time, but it wasn’t like that at all, it was what we pretended, and underneath was exactly what’s happening today : the broken hearts, the looking for love, the lies, the fears." -Jaffe cited in Montagne, 2005. While author Rona Jaffe is here recalling the historical context for her first novel, The Best of Everything, published in 1958, her words have resonance for viewers of Matthew Weiner’s hit show, Mad Men, despite the show’s storyline beginning in 1960. “The Fifties” lasted longer than the decade from 1950 to 1959, and are not bound by those end-dates. January Jones and Jon Hamm as Betty and Don Draper in "Mad Men".

January Jones and Jon Hamm as Betty and Don Draper in "Mad Men". Mad Men is a cultural phenomenon that reflects upon a past era, and exposes a time thought glamorous in its innocent sophistication. It celebrates a time when American consumer capitalism dominated the world discourse through brute strength. With unemployment nearly as high as it was during the Depression, with a bitter war being fought in a distant land, with a country split between conservative aggression and liberal paralysis, Mad Men allows us to pause and reflect on how the ebb and flow of history affects us and how change, no matter how small, is both frighteningly unnerving and assuredly inevitable.

Mad Men is a cultural phenomenon that reflects upon a past era, and exposes a time thought glamorous in its innocent sophistication. It celebrates a time when American consumer capitalism dominated the world discourse through brute strength. With unemployment nearly as high as it was during the Depression, with a bitter war being fought in a distant land, with a country split between conservative aggression and liberal paralysis, Mad Men allows us to pause and reflect on how the ebb and flow of history affects us and how change, no matter how small, is both frighteningly unnerving and assuredly inevitable. Peggy makes a successful bid for Freddy’s office, she is earlier seen exploring the open-plan secretarial floor late one night. A close-up reveals Peggy searching through someone’s desk drawer ; she filches a cigarette, lights it and exhales happily. Then a longer shot shows her stretch luxuriously and sensuously, before wandering off across the office space, usually public, but at night her own private playground. When she inherits Freddy’s former office, Peggy’s pleasure is even greater. She enjoys moving in, having an office boy carry her things, hav ing the other male creatives envy her. She also inherits Freddy’s bar, and is found later by Pete enjoying a solo whiskey. See Elisabeth Moss & Joel Murray in "Mad Men": http://youtu.be/YqU-2QAYWYk

Peggy makes a successful bid for Freddy’s office, she is earlier seen exploring the open-plan secretarial floor late one night. A close-up reveals Peggy searching through someone’s desk drawer ; she filches a cigarette, lights it and exhales happily. Then a longer shot shows her stretch luxuriously and sensuously, before wandering off across the office space, usually public, but at night her own private playground. When she inherits Freddy’s former office, Peggy’s pleasure is even greater. She enjoys moving in, having an office boy carry her things, hav ing the other male creatives envy her. She also inherits Freddy’s bar, and is found later by Pete enjoying a solo whiskey. See Elisabeth Moss & Joel Murray in "Mad Men": http://youtu.be/YqU-2QAYWYk Christina Hendricks as Joan Holloway in "Mad Men"

Christina Hendricks as Joan Holloway in "Mad Men"Gloria Steinem writes in her biography Marilyn/Norma Jean: “She personified many of the secret hopes of men and many secret fears of women”. In the episodes “Maidenform” and “Six Month Leave”, Joan is read by men as a Marilyn-figure and associates herself with the ’50’s screen star and, now, cultural icon. In “Maidenform,” Paul Kinsey pitches an idea to Don on marketing Play tex bras, pleading a case that all women are either a “Jackie” Kennedy or a “Marilyn” Monroe.

Marilyn Monroe in 1950's

Marilyn Monroe in 1950's If Joan is Marilyn, then Betty can be read as a “Jackie”: the wife-and mother who looks after the house and the children. In the same episode he pitches the Play tex campaign Don tells Betty that he doesn’t like her new bright yellow bikini. Betty’s swim gear covers as much if not more than the underwear the Playtex model poses in for the campaign’s image, but Don tells her that the bikini makes her appear desperate.

If Joan is Marilyn, then Betty can be read as a “Jackie”: the wife-and mother who looks after the house and the children. In the same episode he pitches the Play tex campaign Don tells Betty that he doesn’t like her new bright yellow bikini. Betty’s swim gear covers as much if not more than the underwear the Playtex model poses in for the campaign’s image, but Don tells her that the bikini makes her appear desperate. Don firmly separates motherhood and sexual desirability in his own life — going outside his marriage to fulfill his sexual needs. So, while the men at Sterling Cooper may say they want both a “Jackie” and a “Marilyn” we are shown that they want them in different women, not as two sides of the same, as the Play tex campaign implies. “Six Month Leave” positions Joan with Marilyn Monroe, and specifically, with Monroe’s tragic death.

Don firmly separates motherhood and sexual desirability in his own life — going outside his marriage to fulfill his sexual needs. So, while the men at Sterling Cooper may say they want both a “Jackie” and a “Marilyn” we are shown that they want them in different women, not as two sides of the same, as the Play tex campaign implies. “Six Month Leave” positions Joan with Marilyn Monroe, and specifically, with Monroe’s tragic death. Joan and Peggy both grow significantly throughout the first two seasons of "Mad Men." From the first episode, when Joan instructs Peggy on how to use her sexuality to get ahead, to later, when Peggy’s realization that her intelligence is all she needs, both women achieve a personal growth that makes them exciting to watch. “A Night to Remember” ends with Joan rubbing her shoulders where her bra strap has dug in, symbolizing the weight she carries on her shoulders as a woman in a patriarchal society.

Joan and Peggy both grow significantly throughout the first two seasons of "Mad Men." From the first episode, when Joan instructs Peggy on how to use her sexuality to get ahead, to later, when Peggy’s realization that her intelligence is all she needs, both women achieve a personal growth that makes them exciting to watch. “A Night to Remember” ends with Joan rubbing her shoulders where her bra strap has dug in, symbolizing the weight she carries on her shoulders as a woman in a patriarchal society. Episode one of "Mad Men": “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” immediately introduces viewers to the women in Don’s life, juxtaposing Betty as the model suburban wife and mother with counterpart Midge Daniels, the first in a series of mistresses, as well as a bevy of Sterling Cooper secretaries, most with marital ambitions as pointed as their brassieres. Medically speaking, the notorious Victorian “madwoman” is an umbrella figure that runs the gamut from the psychotic murderess to the stifled woman with a nervous cough. She is Betty Draper with her numb hands, or Betty’s gal-pal, Francine, who fantasizes postpartum about poisoning herself and her family as vindication for her husband’s presumed infidelity.

Episode one of "Mad Men": “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” immediately introduces viewers to the women in Don’s life, juxtaposing Betty as the model suburban wife and mother with counterpart Midge Daniels, the first in a series of mistresses, as well as a bevy of Sterling Cooper secretaries, most with marital ambitions as pointed as their brassieres. Medically speaking, the notorious Victorian “madwoman” is an umbrella figure that runs the gamut from the psychotic murderess to the stifled woman with a nervous cough. She is Betty Draper with her numb hands, or Betty’s gal-pal, Francine, who fantasizes postpartum about poisoning herself and her family as vindication for her husband’s presumed infidelity. In the nineteenth century she is most commonly the “hysterical” woman, like Peggy Olson protecting her respectability by mentally repressing her full-term pregnancy with a complete psychotic break. Pedestrian rhetoric, however, is apt loosely to brand any woman who deviates from the norm as “mad.” Madness, therefore, is a label that envelopes any woman who moves beyond that realm of femininity that is familiar and, thus, viewed as “natural.”

In the nineteenth century she is most commonly the “hysterical” woman, like Peggy Olson protecting her respectability by mentally repressing her full-term pregnancy with a complete psychotic break. Pedestrian rhetoric, however, is apt loosely to brand any woman who deviates from the norm as “mad.” Madness, therefore, is a label that envelopes any woman who moves beyond that realm of femininity that is familiar and, thus, viewed as “natural.” Just how natural this learned femininity is, however, extremely suspect, as argued famously by John Stuart Mill in The Subjection of Women: “What is now called the nature of women is an eminently artificial thing — the result of forced repression in some directions, unnatural stimulation in others”. Mill argues that women’s (and presumably men’s) nature can not truly be known since it is manipulated and distorted from infancy into becoming the socialized, gendered creature we recognize, yet the product is so pervasive that we attribute the result to God’s design instead of our own making.

Just how natural this learned femininity is, however, extremely suspect, as argued famously by John Stuart Mill in The Subjection of Women: “What is now called the nature of women is an eminently artificial thing — the result of forced repression in some directions, unnatural stimulation in others”. Mill argues that women’s (and presumably men’s) nature can not truly be known since it is manipulated and distorted from infancy into becoming the socialized, gendered creature we recognize, yet the product is so pervasive that we attribute the result to God’s design instead of our own making. The fallen woman is a familiar warning to the Victorian reader, but the plight of this figure is much farther reaching. Peggy, for example, is merely another in a long literary tradition of fallen women. British letters alone gave rise to infamous eighteenth- and nineteenth-century examples of fallenness: Clarissa, Moll Flanders, Lady Dedlock, Tess Durbeyfield, Ruth, Esther Waters, and the Lady of Shalott. Beyond England, European authors contribute Emma Bovary, Anna Karenina, and Hedda Gabler. Given our shared literary heritage, America also demonstrates a clear preoccupation with women’s virtue and the fallen woman: Charlotte Temple, Hester Prynne, Crane’s Maggie, Ellen Olenska, Edna Pontelier, Carrie Meeber and Jennie Gerhardt, Daisy Miller, and Lena Grove.

The fallen woman is a familiar warning to the Victorian reader, but the plight of this figure is much farther reaching. Peggy, for example, is merely another in a long literary tradition of fallen women. British letters alone gave rise to infamous eighteenth- and nineteenth-century examples of fallenness: Clarissa, Moll Flanders, Lady Dedlock, Tess Durbeyfield, Ruth, Esther Waters, and the Lady of Shalott. Beyond England, European authors contribute Emma Bovary, Anna Karenina, and Hedda Gabler. Given our shared literary heritage, America also demonstrates a clear preoccupation with women’s virtue and the fallen woman: Charlotte Temple, Hester Prynne, Crane’s Maggie, Ellen Olenska, Edna Pontelier, Carrie Meeber and Jennie Gerhardt, Daisy Miller, and Lena Grove. Consequently, most of the women of Mad Men are “fallen” if held to a Victorian standard, and, if not, are at least sexually loose if held to the acknowledged sexual standard of their day. Even if women in 1960 are on the brink of sexual revolution, remnant feelings about female respectability — being the type of girl you marry rather than the type of girl you “date”— nevertheless linger, and this tightrope walk is evident in the struggles of Mad Men’s women.

Consequently, most of the women of Mad Men are “fallen” if held to a Victorian standard, and, if not, are at least sexually loose if held to the acknowledged sexual standard of their day. Even if women in 1960 are on the brink of sexual revolution, remnant feelings about female respectability — being the type of girl you marry rather than the type of girl you “date”— nevertheless linger, and this tightrope walk is evident in the struggles of Mad Men’s women. Interestingly, when these images metaphorically depict the fragility of domestic harmony — as implied through subtle icons like the house of cards — this usually implies that the responsibility lies with the woman since it is her indiscretion alone that will tear the family asunder. In the Drapers’ case, the threat is twofold: aside from Betty’s infidelity, the second threat is that Betty might not take Don back which, again, would result in the collapse of the family structure.

Interestingly, when these images metaphorically depict the fragility of domestic harmony — as implied through subtle icons like the house of cards — this usually implies that the responsibility lies with the woman since it is her indiscretion alone that will tear the family asunder. In the Drapers’ case, the threat is twofold: aside from Betty’s infidelity, the second threat is that Betty might not take Don back which, again, would result in the collapse of the family structure. This scenario, in fact, plays out at the end of Season Three when Betty blames Don for ruining every thing (“The Grown-Ups”). Don, as usual, deflects responsibility, recognizing only that it is Betty who seeks to “break up” the family when she hires a divorce attorney (“Shut the Door. Sit Down.”) -from "Analyzing Mad Men: Critical Essays" by Scott F. Stoddart

This scenario, in fact, plays out at the end of Season Three when Betty blames Don for ruining every thing (“The Grown-Ups”). Don, as usual, deflects responsibility, recognizing only that it is Betty who seeks to “break up” the family when she hires a divorce attorney (“Shut the Door. Sit Down.”) -from "Analyzing Mad Men: Critical Essays" by Scott F. Stoddart