Jake Gyllenhaal (with Laura Dern and Mark Ruffalo) attending the Spirit Silver Lake Film Festival Awards, on 16th April, 2004 in LA

Jake Gyllenhaal (with Laura Dern and Mark Ruffalo) attending the Spirit Silver Lake Film Festival Awards, on 16th April, 2004 in LA

Jake Gyllenhaal, out and about in Beverly Hills, on 3rd December 2011

Jake Gyllenhaal, out and about in Beverly Hills, on 3rd December 2011

TAKING A WALK ON THE FILMIC SIDE, TRANSITING THE VINTAGE ROADS.

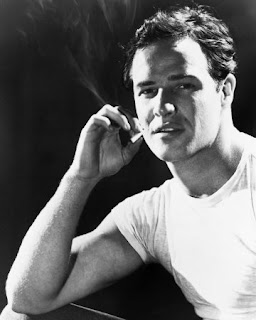

Ann Sheridan and John Garfield in "Castle On The Hudson" (1940) directed by Anatole Litvak

Ann Sheridan and John Garfield in "Castle On The Hudson" (1940) directed by Anatole Litvak "John Garfield plays Tommy Gordon, a small time hood who is working his way to the top against the wishes of his girlfriend Kay Manners, played by Ann Sheridan. When he forgets it's his bad luck night (Saturday) and pulls a job anyway, naturally he gets caught.

"John Garfield plays Tommy Gordon, a small time hood who is working his way to the top against the wishes of his girlfriend Kay Manners, played by Ann Sheridan. When he forgets it's his bad luck night (Saturday) and pulls a job anyway, naturally he gets caught. Kay visits him in prison and says she's working with his lawyer to get him out. Gordon doesn't trust his lawyer, thinking he's making a play for Kay, and tells her to stay away from him. Gordon soon befriends a couple of cons played by Burgess Meredith, the smart guy, and Guinn "Big Boy" Williams, a dumb lug and they all hatch a plan to escape. On the night of the escape, Gordon realizes it's Saturday night and refuses to leave his cell.

Kay visits him in prison and says she's working with his lawyer to get him out. Gordon doesn't trust his lawyer, thinking he's making a play for Kay, and tells her to stay away from him. Gordon soon befriends a couple of cons played by Burgess Meredith, the smart guy, and Guinn "Big Boy" Williams, a dumb lug and they all hatch a plan to escape. On the night of the escape, Gordon realizes it's Saturday night and refuses to leave his cell. Later, Gordon is summoned by the warden and told that Kay has been in an auto accident and isn't expected to live. If Gordon will promise to come back, the warden will let him go to see her. He promises to return even if it means the chair. As he's leaving the warden's office, he notices that it's Saturday but goes on anyway. On his way to see Kay, Gordon picks up a tail from a policeman who can't believe what he's seeing.

Later, Gordon is summoned by the warden and told that Kay has been in an auto accident and isn't expected to live. If Gordon will promise to come back, the warden will let him go to see her. He promises to return even if it means the chair. As he's leaving the warden's office, he notices that it's Saturday but goes on anyway. On his way to see Kay, Gordon picks up a tail from a policeman who can't believe what he's seeing. When Gordon gets to the bedridden Kay, he learns that his lawyer was indeed moving in on her and was the cause of her injuries. He takes her gun and starts to leave to settle the matter when Kay convinces him not to and to give her the gun. About that time, the lawyer shows up and the two men start fighting. When the lawyer appears to get the upper hand, Kay shoots him. The policemen hears the shot and tries to force Kay's apartment door. Gordon flees with the gun and the lawyers money.

When Gordon gets to the bedridden Kay, he learns that his lawyer was indeed moving in on her and was the cause of her injuries. He takes her gun and starts to leave to settle the matter when Kay convinces him not to and to give her the gun. About that time, the lawyer shows up and the two men start fighting. When the lawyer appears to get the upper hand, Kay shoots him. The policemen hears the shot and tries to force Kay's apartment door. Gordon flees with the gun and the lawyers money. Gordon hooks up with his old gang and arranges for safe passage out of town on a boat. However, upon reading the headlines and seeing that the warden will lose his position for letting him go, he decides to return. Kay insists she shot the lawyer but nobody believes her and Gordon is sentenced to die. The ending of the film is very good, with Williams having to face his fate before Garfield, John Litel as the prison chaplain, and a couple of more scenes with Sheridan and O'Brien as Gordon faces his fate". Source: www.classicfilmguide.com

Gordon hooks up with his old gang and arranges for safe passage out of town on a boat. However, upon reading the headlines and seeing that the warden will lose his position for letting him go, he decides to return. Kay insists she shot the lawyer but nobody believes her and Gordon is sentenced to die. The ending of the film is very good, with Williams having to face his fate before Garfield, John Litel as the prison chaplain, and a couple of more scenes with Sheridan and O'Brien as Gordon faces his fate". Source: www.classicfilmguide.com Ann Sheridan made seven films in 1938, including "Angels With Dirty Faces" with James Cagney.

Ann Sheridan made seven films in 1938, including "Angels With Dirty Faces" with James Cagney. She was named Max Factor’s Girl of the Year in 1939.

She was named Max Factor’s Girl of the Year in 1939. Ann Sheridan and Ronald Reagan in "Kings Row" (1942) directed by Sam Wood. Ann's role Randy Monaghan in "Kings Row" was her favorite performance of her career. Bogart had tipped Ann off about it before the filming entered in production.

Ann Sheridan and Ronald Reagan in "Kings Row" (1942) directed by Sam Wood. Ann's role Randy Monaghan in "Kings Row" was her favorite performance of her career. Bogart had tipped Ann off about it before the filming entered in production. Carole Landis with fellow actress Ann Sheridan

Carole Landis with fellow actress Ann Sheridan Once refusing the role in "Strawberry Blonde" (1941) directed by Raoul Walsh, because she'd played too many like that already. That role went to Rita Hayworth.

Once refusing the role in "Strawberry Blonde" (1941) directed by Raoul Walsh, because she'd played too many like that already. That role went to Rita Hayworth. Another of Sheridan's walkouts was over a salary dispute -- she was earning $700 a week and, being one of the studio's top assets, she felt she should get $2000. In the war years she was one of the handful of stars who traveled to the faraway corners of the global conflicts to entertain the troops almost on the line of fire.

Another of Sheridan's walkouts was over a salary dispute -- she was earning $700 a week and, being one of the studio's top assets, she felt she should get $2000. In the war years she was one of the handful of stars who traveled to the faraway corners of the global conflicts to entertain the troops almost on the line of fire. Bette Davis and John Garfield looking at plans for the Hollywood Canteen

Bette Davis and John Garfield looking at plans for the Hollywood Canteen Ann Sheridan signs autographs for enlisted men at the Hollywood Canteen in 1943

Ann Sheridan signs autographs for enlisted men at the Hollywood Canteen in 1943 In her words, regarding James Cagney and Pat O'Brien: "They raised me. I was a brat running around who they could pick on. I was certainly fond of them and they seemed pretty fond of me. All the people on the lot were pretty wonderful, we all got along."

In her words, regarding James Cagney and Pat O'Brien: "They raised me. I was a brat running around who they could pick on. I was certainly fond of them and they seemed pretty fond of me. All the people on the lot were pretty wonderful, we all got along." Regarding John Garfield: "John Garfield was a dear man. He was like the little guy who brought the apple for the teacher."

Regarding John Garfield: "John Garfield was a dear man. He was like the little guy who brought the apple for the teacher." Ann said she loved Humphrey Bogart and Errol Flynn. Source: www.altfg.com

Ann said she loved Humphrey Bogart and Errol Flynn. Source: www.altfg.com After Sheridan and Humphrey Bogart co-starred in "San Quentin" (1937) directed by Lloyd Bacon, in which their characters were siblings, they became friends and began referring to each other as Sister Annie and Brother Bogie.

After Sheridan and Humphrey Bogart co-starred in "San Quentin" (1937) directed by Lloyd Bacon, in which their characters were siblings, they became friends and began referring to each other as Sister Annie and Brother Bogie. Humphrey Bogart and Ann Sheridan in "It All Came True" (1940) directed by Lewis Seiler

Humphrey Bogart and Ann Sheridan in "It All Came True" (1940) directed by Lewis Seiler

Ann Sheridan with Humphrey Bogart and George Raft in "They Drive by Night" (1940) directed by Raoul Walsh

Ann Sheridan with Humphrey Bogart and George Raft in "They Drive by Night" (1940) directed by Raoul Walsh In their Ann Sheridan obituary the London Times said: "Without ever achieving the mythic status of a superstar, she was always a pleasure to watch, and, as with all true stars, was never quite like anyone else". Very true words, I concur.

In their Ann Sheridan obituary the London Times said: "Without ever achieving the mythic status of a superstar, she was always a pleasure to watch, and, as with all true stars, was never quite like anyone else". Very true words, I concur.

James Stewart as Ransom Stoddard in "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" (1962) directed by John Ford

James Stewart as Ransom Stoddard in "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" (1962) directed by John Ford Bingham’s "Acting Male" is closer to a ‘star study’ of three actor case studies - Robert Sklar’s "City Boys: Cagney, Bogart, Garfield" is similar in this regard.

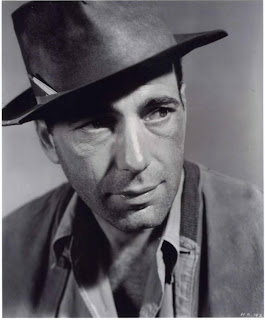

Bingham’s "Acting Male" is closer to a ‘star study’ of three actor case studies - Robert Sklar’s "City Boys: Cagney, Bogart, Garfield" is similar in this regard. John Garfield as Tony Fenner in "We Were Strangers" (1949) directed by John Houston

John Garfield as Tony Fenner in "We Were Strangers" (1949) directed by John Houston Humphrey Bogart as Paul Fabrini in "They drive by night" (1940) directed by Raoul Walsh

Humphrey Bogart as Paul Fabrini in "They drive by night" (1940) directed by Raoul Walsh And Cagney "does not merely inhabit or present [the figure of Tom Bowers in The Public Enemy]...he creates it...His short, quick movements, his clipped diction, his mobile eyes and mouth, are counterpointed with...an almost sultry languor". -Kirkus Reviews.

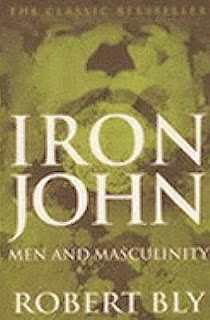

And Cagney "does not merely inhabit or present [the figure of Tom Bowers in The Public Enemy]...he creates it...His short, quick movements, his clipped diction, his mobile eyes and mouth, are counterpointed with...an almost sultry languor". -Kirkus Reviews. Robert Bly’s "Iron John: A Book About Men" is noteworthy for its engagement with the idea of masculinity as a collective and communal practice. Bly admires the stoicism of the ‘fifties male’, bemoans the feminine ‘soft male’ of the 1970s and calls for men to uncover the ‘deep’ masculinity inherent in all men than has been hidden as a result of social and cultural changes of the past few decades, articularly feminism. In this way, Bly’s work appears to conform to a wider pattern in film and masculinity studies in seeing masculinity as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’.

Robert Bly’s "Iron John: A Book About Men" is noteworthy for its engagement with the idea of masculinity as a collective and communal practice. Bly admires the stoicism of the ‘fifties male’, bemoans the feminine ‘soft male’ of the 1970s and calls for men to uncover the ‘deep’ masculinity inherent in all men than has been hidden as a result of social and cultural changes of the past few decades, articularly feminism. In this way, Bly’s work appears to conform to a wider pattern in film and masculinity studies in seeing masculinity as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’. Social historians such as Michael Kimmel have attempted to locate crises of masculinity historically, quantifying them schematically according to dominant social positions such as ‘profeminist, antifeminist, and promale’. Kimmel defines crises of masculinity as cultural and historical ‘moments of gender confusion that assume a prominent position in the public consciousness’, offering examples in Restoration England (1688–1714) and the US in the years 1880 to 1914.

Social historians such as Michael Kimmel have attempted to locate crises of masculinity historically, quantifying them schematically according to dominant social positions such as ‘profeminist, antifeminist, and promale’. Kimmel defines crises of masculinity as cultural and historical ‘moments of gender confusion that assume a prominent position in the public consciousness’, offering examples in Restoration England (1688–1714) and the US in the years 1880 to 1914. Harrison Ford as Henry Turner in "Regarding Henry" (1991) directed by Mike Nichols

Harrison Ford as Henry Turner in "Regarding Henry" (1991) directed by Mike Nichols Ultimately, these position pieces argue that the masculine tropes described emerge from a critical convergence of events shaping masculine identities during specified periods. Masculinity, as scholars such as R. W. Connell have pointed out, is a fluid identity and constantly in flux. Since what constitutes ‘being a man’ continually changes according to the particular social or cultural moment, adapt, change and, in effect, recycle their male identities. Yet movement too far in either direction is considered to undermine masculinity.

Ultimately, these position pieces argue that the masculine tropes described emerge from a critical convergence of events shaping masculine identities during specified periods. Masculinity, as scholars such as R. W. Connell have pointed out, is a fluid identity and constantly in flux. Since what constitutes ‘being a man’ continually changes according to the particular social or cultural moment, adapt, change and, in effect, recycle their male identities. Yet movement too far in either direction is considered to undermine masculinity. Edward Norton and Brad Pitt as The Narrator and Taylor Durden in "Fight Club" (1999) directed by David Fincher

Edward Norton and Brad Pitt as The Narrator and Taylor Durden in "Fight Club" (1999) directed by David Fincher Although Palahniuk said in interviews that he had not read "Iron John", Tyler and Jack (played by Edward Norton in the film) could have been lifted from its pages, resonating themes of father loss and overdependence on the mother, initiation ceremonies (head shaving), and the supposedly feminising effects of consumer culture.

Although Palahniuk said in interviews that he had not read "Iron John", Tyler and Jack (played by Edward Norton in the film) could have been lifted from its pages, resonating themes of father loss and overdependence on the mother, initiation ceremonies (head shaving), and the supposedly feminising effects of consumer culture. Jack moves into Tyler’s dilapidated house and they start an underground boxing club to give men the opportunity to release their primal aggression and reclaim their sense of masculinity. When the fight clubs become a national success, Tyler decides to ‘take it up a notch’ and Project Mayhem is born: a full-scale anti-capitalist terrorist organisation with the ultimate aim of overthrowing corporate America and eradicating consumer debt.

Jack moves into Tyler’s dilapidated house and they start an underground boxing club to give men the opportunity to release their primal aggression and reclaim their sense of masculinity. When the fight clubs become a national success, Tyler decides to ‘take it up a notch’ and Project Mayhem is born: a full-scale anti-capitalist terrorist organisation with the ultimate aim of overthrowing corporate America and eradicating consumer debt. However, women are ultimately more threatening to men than consumerism and Tyler’s misogyny culminates in his verbal and emotional response to Marla (Helena Bonham Carter); women are ‘tumours’, ‘scratches on the roof of your mouth’, and ‘predators posing as house pets’.

However, women are ultimately more threatening to men than consumerism and Tyler’s misogyny culminates in his verbal and emotional response to Marla (Helena Bonham Carter); women are ‘tumours’, ‘scratches on the roof of your mouth’, and ‘predators posing as house pets’. At the same time, in labelling herself as ‘infectious waste’, Marla corroborates the image of women as dirty and contaminated, further reinforced by Tyler’s donning of rubber gloves during a sexual encounter.

At the same time, in labelling herself as ‘infectious waste’, Marla corroborates the image of women as dirty and contaminated, further reinforced by Tyler’s donning of rubber gloves during a sexual encounter. Representations of the 'Wild Man' in "Fight Club" explicitly model themselves in opposition to the figure of the 'Wimp'. Tyler Durden’s 'Wild Man' is repeatedly set against Jack, whose softness is amplified when framed in conjunction with Tyler’s hypermasculinity. "Fight Club" demonstrates a self-conscious awareness of this opposition by playing with the conventions of masculinity and femininity. -"Masculinity and Film Performance: Male Angst in Contemporary American Cinema" by Donna Peberdy (2011)

Representations of the 'Wild Man' in "Fight Club" explicitly model themselves in opposition to the figure of the 'Wimp'. Tyler Durden’s 'Wild Man' is repeatedly set against Jack, whose softness is amplified when framed in conjunction with Tyler’s hypermasculinity. "Fight Club" demonstrates a self-conscious awareness of this opposition by playing with the conventions of masculinity and femininity. -"Masculinity and Film Performance: Male Angst in Contemporary American Cinema" by Donna Peberdy (2011)

Frank: That other girl. She don't mean anything to me.

Frank: That other girl. She don't mean anything to me. Cora: Oh Frank, I couldn't turn you into Sackett. I couldn't have this baby and then have it find out that I'd sent its father into that poison gas chamber for murder.

Cora: Oh Frank, I couldn't turn you into Sackett. I couldn't have this baby and then have it find out that I'd sent its father into that poison gas chamber for murder. "Some elements of 'The Postman Always Rings Twice' sprang from real life, notably the infamous Ruth Snyder murder case, in which the defendant murdered her husband with the help of her lover, who she then tried to poison. Cora was modeled on a girl who pumped Cain's gas at a service station. She was kind of cheap, Cain acknowledged (more like the Cora of the novel than the Cora of the motion picture, who just seemed too classy to be working in a cheap roadside diner), but so sexy that she stuck in his memory". Source: bernardschopen.tripod.com

"Some elements of 'The Postman Always Rings Twice' sprang from real life, notably the infamous Ruth Snyder murder case, in which the defendant murdered her husband with the help of her lover, who she then tried to poison. Cora was modeled on a girl who pumped Cain's gas at a service station. She was kind of cheap, Cain acknowledged (more like the Cora of the novel than the Cora of the motion picture, who just seemed too classy to be working in a cheap roadside diner), but so sexy that she stuck in his memory". Source: bernardschopen.tripod.com When they are way out in the deep dark ocean and Cora tiredly struggles to stay afloat, she asks for him to either save her from drowning and pledge to restore their love, or leave her to perish. Frank rescues his exhausted lover.

When they are way out in the deep dark ocean and Cora tiredly struggles to stay afloat, she asks for him to either save her from drowning and pledge to restore their love, or leave her to perish. Frank rescues his exhausted lover. Cora: What I wanted to be sure of was, whether you trust me, if you don't believe that I can ever turn on you again. I'm too tired. I could never make it alone. Nobody'll ever know.

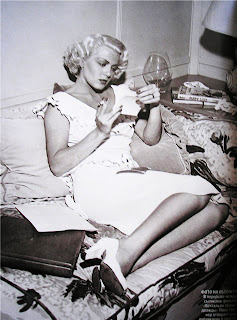

Cora: What I wanted to be sure of was, whether you trust me, if you don't believe that I can ever turn on you again. I'm too tired. I could never make it alone. Nobody'll ever know. Lana Turner as Cora Smith in 'The Postman Aways Rings Twice'

Lana Turner as Cora Smith in 'The Postman Aways Rings Twice'