Although Classical Hollywood had already been dealt a series of death-blows, it might have taken a much longer time dying had it not been for the major eruptions in American culture from the mid-sixties and into the 1970s. Overwhelmingly, the echoes of Vietnam, and subsequently Watergate, were part of the growing force and cogency of radical protest movements—black militancy, feminism, gay liberation. There are two keys to understanding the development of the Hollywood cinema in the seventies: the impingement of Vietnam on the national consciousness, and the astonishing evolution of the horror film genre. The obvious monstrousness of the Vietnam war definitively undermined the credibility of “the system”. Popular protest became common, the essential precondition to a valid revolution. The questioning of authority spread to a questioning of the entire social structure that validated it, and ultimately social institutions, the family, the symbolic figure of the father as superego. The possibility suddenly opened up that the whole world might have to be recreated. Yet this generalized crisis in ideological confidence never begat a revolution. Society appeared to be in a state of advanced disintegration, yet there was no serious possibility of the emergence of a coherent alternative.

Central to the incoherence of Taxi Driver (1976) is its director Martin Scorsese, with his Catholic Italian background, his fascination with the Hollywood tradition, and his comparatively open responsiveness to contemporary issues. Travis (De Niro) becomes obsessed with the mission of washing the scum from the streets—the scum being both literal and human flotsam. The outcome of this obsession is his violent final release and the rescue of Iris in order to send her back to her parents, the act that establishes Travis as a hero in the eyes of society and the popular press. We see the big city is pure filth, Betsy as the angel of true love is an illusion; so what is left? During one of Travis’ conversation with Iris, he asks her if there is any place she wants to go to escape the squalor of her current existence. She replies tentatively that she has heard about “a commune in Vermont.” But Travis dismisses it immediately: he once saw a picture of a commune in a magazine and it “didn’t look clean.”

Travis’ behavior is presented as increasingly pathological and antisocial, with his new ambitions he's become more insane (among his plans, an assassination of a politician). Yet the film can neither clearly reject him (Travis remains, somehow, The Film Hero). I don't think anyone doubts that Travis’ finger-to-forehead gesture of mock suicide is ironically made, yet the irony seems curiously unfocused, and its aim is uncertain. The effect for the viewer is of a kind of paralysis. Being unable to achieve any clear, definitive statement about the hero, the film retreats into enigma. Travis becomes a public hero (ironic), feels satisfaction at what he has done for Iris and her parents, and reaches some personal serenity and satisfaction with himself. The spectator can think either that the hero will continue to cleanse the city of its filth, and he will explode again with another bloodbath. There is another alternative, which comes closest to rendering the action and narrative intelligible—the notion that Travis, while drowning in an obviously beyond-help society, has achieved through his massacre some kind of personal grace or redemption, and that is really all that matters, since civilization is demonstrably unredeemable.

Joe (1970) takes place over several days in New York City and focuses on the unlikely relationship that develops between two middle-age men: Joe Curran (Peter Boyle), a bitter tool-and-dye maker, and Bill Compton (Dennis Patrick), a wealthy advertising executive. While they have nothing in common socially or personally, they share a deep resentment toward hippie youth culture and the radical shifts in the American society. Joe is ranting and raving about “niggers,” “fags,” and “hippies,” grousing about his perceived disenfranchisement and an unfair system that coddles the lazy and punishes honest workers like himself. There is always the suggestion that Bill is just trying to stay on Joe’s good side out of concern that Joe might turn him in to the police, but the film also wants us to believe that these two men forge a real connection, one that feeds off their collective anger.

Of course, that anger, to some extent, derives from jealousy, and when they have the opportunity late in the film to participate in an orgy with a group of hippies, their hesitation is minimal. They see the youth generation as cultural rot, but rot they want a part of, yet they can’t really share. At its best, Joe captures with raw, direct power the intensity of cultural animosity—one might say loathing—that was gripping the nation at the time, and in some ways it was prophetic; it was made just before the Kent State shooting and the subsequent Hard Hat Riot in New York City, both events that Joe Curran would have endorsed. The script merges zeitgeist-defining cultural awareness with a streak of vigilantism that is at times critical and at other times dangerously regressive. It’s hard to get a read on what the film’s ideological positioning is, which is compounded by Wexler’s choice of a contrived scenario about the violence of the generation gap.

Peter Boyle embodies the embittered Joe with a unique mix of angry bluster, coldness, foolish naivete, and dangerously coiled rage. He is simulatenousyl pathetic and scary, yet there is something relatable about him, even as he blurts out his generally misanthropic view of the world. In an interview with The New York Times, Boyle expressed his dismay that certain audiences misread the film and even cheered Joe’s violence (he contended that Joe was a clear anti-violence cry against U.S. involvement in Vietnam). The film seems to condemn Joe’s regressive social attitudes and love of violence, yet the objects of his derision are largely deserving, as most of the hippies portrayed in the film are criminals and frauds who betray any sense of progressive values or morality (it is clearly a post-Manson hippie world).

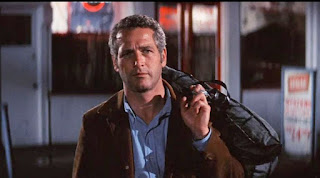

One of the great joys of Stuart Rosenberg’s WUSA (1970) is the way it evokes the New Orleans that was still visible but disappearing even in the 1980s—the Canal Street department stores, the French Quarter dives, the jazz clubs, the bars with wood paneling. If that New Orleans resembled anything, it resembled the blue collar city that disappeared when the dot com boom remade San Francisco in the early 1990s. The YMCA building on Saint Charles Avenue was long gone, as was the Hummingbird Grill, an all-night diner on the ground floor of a residential hotel where ex-cons worked the grill, and the waitresses brought you a thermos when you ordered coffee. Oddly, WUSA can’t seem to make up its mind whether it wants to glorify or condemn Reinhardt’s moral apathy. In fact, apart from fringe elements on both sides of the political spectrum, moral apathy seems to be the defining characteristic of just about everybody in the movie. As in Yeats’s poem, in WUSA, only the worst are full of “passionate intensity.”

Reinhardt finds work as a disc jockey on WUSA; though he identifies as “liberal,” he doesn’t mind reading news with an openly conservative spin. In short order, Reinhardt and Geraldine (Joanne Woodward) move into an apartment in the French Quarter, meeting a group of disaffected hippies and Rainey (Anthony Perkins), a liberal southerner (also a judge’s son) who after a stint in Venezuela with the Peace Corps, has come home and started collecting data on New Orleans welfare recipients for some vague municipal entity. Rainey excoriates Reinhardt for working for WUSA, which pushes Reinhardt to a state of self-delusion. In the film, Newman turns in such a charismatic performance, it’s kind of a contradiction, since the apathy he makes so appealing runs contrary to what would seem to be the movie’s left-leaning political message. When he’s not with Geraldine or working at the radio station, Reinhardt spends most of his time drinking and getting high with the hippies downstairs, who seem as unfazed as him. Along with Reinhardt, they sneer openly at Rainey, the only idealist.

In the novel, all three protagonists, Reinhardt, Geraldine and Rainey are self-destructive. In their film version, Paul Newman’s charisma, his on-screen chemistry with Joanne Woodward, and Anthony Perkins' obsessive personality, all cause the film to express a worldview much closer to Reinhardt’s ultra-individualism than it is to Rainey’s sincere, if somewhat patronizing liberalism—which is a problem, since the movie clearly wants us to sympathize with Rainey’s convictions. If this constitutes one of WUSA’s chief failures, nevertheless, it also makes the movie suggestive of the contradictory philosophical underpinnings of American counterculture, and maybe one of the reasons for becoming the biggest flop of Paul Newman’s career.

Over Neil Diamond's song Glory Road in a montage, Reinhardt walks through a derelict graveyard, grieving Geraldine while trying to find her tomb. In the movie’s final scene, ruefully, Reinhardt tells the hippie guru that he is “a survivor.” Then he flings his jacket over his shoulder and walks out the door, presumably to board yet another Greyhound for a different city. WUSA captures much that was (and is) wrong with American counterculture, which suffers from deeply conflicted philosophical underpinnings, not least the conflict between the individualism at all costs of Reinhardt and the communalism inherent in any leftist critique. Consider the hippies living below Reinhardt, who openly have mocked Rainey for not being “cool.” By all appearances, they’re card carrying members of the American counterculture of the time, and yet throughout the film, they behave so inconsistently. Granted, we realize Rainey is disturbed enough to resort to violence. And yet while the film’s hippies mock Rainey’s idealism, they seem untroubled by Reinhardt’s opportunism. Does this make them opportunists, or worse, radical capitalists?

If anything, the movie posits a world where everybody’s on the grift, from Reinhart’s preacher friend (a conman from New York) to the African-Americans who are dependent on welfare. In point of fact, the WUSA conservatives have it right; in both the film and the novel, most of the welfare recipients Rainey interviews are collecting benefits fraudulently, a fact that only serves to justify Reinhardt’s moral apathy. In WUSA, the closest Reinhardt comes to a change of heart is a speech condemning the Vietnam War at the film’s climax. “When our boys drop a napalm bomb on a cluster of gibbering slants, it’s a bomb with a heart.” As a parody of Newspeak, Reinhardt continues, while the rally turns into a riot. “And inside the heart of that bomb, mysteriously but truly present, is a fat little old lady on the way to the World’s Fair, and that lady is as innocent as she is motherly.” And yet by the time Reinhardt’s lecturing us from the podium, the film’s one committed leftist, Rainey, is being beaten to death by an angry mob.

In one scene, Reinhardt and Geraldine take a night swim in Lake Pontchartrain. After they get out of the water, Reinhardt accuses Geraldine of being a “man-killer” for luring him into the lake. Is he really so paranoid? Among other things, in WUSA, we observe the uneasy relationship countercultural values have with traditional American ideas about maleness, and with the American mythology of the outsider as both hero and anti-hero, at odds with most leftist ideology. In A Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations (1991) Christopher Lasch argues that much of what passes for counterculture is countercultural in appearance only, since it actually apes the values of the mainstream culture; as an example, Lasch cites 1960s countercultural icon Jim Morrison, frontman of the commercial rock band The Doors. In WUSA, won over by the star’ charisma, we might forget Reinhardt’s apathy, and the film would seem to contradict itself. Nevertheless, in part because Newman embodies such a glaring contradiction, the film tells us a great deal about the contradictory forces shaping American culture both before and since it was made. —Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan and Beyond: A Revised and Expanded Edition (2003) by Robin Wood

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)