Douglas Caddy: This morning (08/06/020) I had a cup of coffee at a donut shop in Houston with a friend, Philip Dyer. I casually mentioned to him that I had recently viewed The JFK Assassination: The Garrison Tapes directed by John Barbour and I was impressed with his work. Phil then told me that he had met Clay Shaw in New Orleans sometime after Shaw had been found innocent by the jury in the trial brought by Garrison. This occurred while Phil was visiting his close friend, Bill Howard, who was New Orleans' premier interior decorator, and Howard invited him to join an unnamed friend that he planned to have breakfast with. Upon arrival at the restaurant Howard surprised Phil by introducing him Clay Shaw who was already seated. Phil said that Shaw was impeccably dressed and had piercing blue eyes. Because Howard was a close friend of Shaw and Phil was a close friend of Howard, Shaw was relaxed in his conversation at breakfast. So Phil decided to ask him whether he knew Lee Harvey Oswald. Phil told me that Shaw replied, "I knew Lee very, very well." Phil then asked Shaw whether he believed Oswald killed President Kennedy. Shaw replied, "You need to know that Lee Harvey Oswald was a patsy." Later that day Howard invited Phil to join him in attending a party at the residence of Tennessee Williams. Phil said they walked from Howard's residence in the French Quarter to Williams' house that had an immense back yard of grass, so it was likely in the nearby Garden District.

Phil said there were a hundred people at the party and they were the most beautiful people he had ever seen. I remarked to Phil that it was tragic the way Tennessee Williams later died swallowing a bottle cap that got lodged in his windpipe in his throat. It is amazing how some celebrities leave this world. Nelson Rockefeller had a heart attack while having sex with a young woman, Andy Warhol died of neglect in New York Hospital, and Dorothy Kilgallen allegedly died of a drug overdose but more likely of murder. So just add Tennessee Williams to the list. Phil Dyer is my closest friend in Houston. I have known him for years. He had told me this story before several times but it wasn't until I listened to The Garrison Tapes recently that I realized the significance of it. Phil is extremely intelligent and I said to him that what he had told me about meeting Clay Shaw and what Shaw had said made him a supremely important witness to history. I do not know whether Phil at this late stage in his life is willing to go public with what he knows and as a result become a public figure with all the headache and controversy that goes with that. I do think he would be agreeable to having a phone conversation with Jim DiEugenio so that Jim as a historian would be able to vouch later as to what Phil told me in the conversation. Source: educationforum.ipbhost.com

Jill Abramson, New York Times’s executive editor: An estimated 40,000 books about JFK have been published since his death. Readers can choose from many books but surprisingly few good ones, and, maybe with the exception of JFK & the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters by James W. Douglass, not really outstanding ones. It is a curious state of affairs, and some of the nation’s leading historians wonder about it. “There is such fascination in the country about the 50th anniversary, but there is no a great book about Kennedy,” Robert Caro lamented. The situation is all the stranger since Kennedy’s life and death form “one of the great American stories.” Caro should know. His epic biography of Lyndon B. Johnson brilliantly captures parts of the Kennedy saga, especially the assassination in Dallas, revisited in the latest installment, “The Passage of Power.”

Phil said there were a hundred people at the party and they were the most beautiful people he had ever seen. I remarked to Phil that it was tragic the way Tennessee Williams later died swallowing a bottle cap that got lodged in his windpipe in his throat. It is amazing how some celebrities leave this world. Nelson Rockefeller had a heart attack while having sex with a young woman, Andy Warhol died of neglect in New York Hospital, and Dorothy Kilgallen allegedly died of a drug overdose but more likely of murder. So just add Tennessee Williams to the list. Phil Dyer is my closest friend in Houston. I have known him for years. He had told me this story before several times but it wasn't until I listened to The Garrison Tapes recently that I realized the significance of it. Phil is extremely intelligent and I said to him that what he had told me about meeting Clay Shaw and what Shaw had said made him a supremely important witness to history. I do not know whether Phil at this late stage in his life is willing to go public with what he knows and as a result become a public figure with all the headache and controversy that goes with that. I do think he would be agreeable to having a phone conversation with Jim DiEugenio so that Jim as a historian would be able to vouch later as to what Phil told me in the conversation. Source: educationforum.ipbhost.com

Jill Abramson, New York Times’s executive editor: An estimated 40,000 books about JFK have been published since his death. Readers can choose from many books but surprisingly few good ones, and, maybe with the exception of JFK & the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters by James W. Douglass, not really outstanding ones. It is a curious state of affairs, and some of the nation’s leading historians wonder about it. “There is such fascination in the country about the 50th anniversary, but there is no a great book about Kennedy,” Robert Caro lamented. The situation is all the stranger since Kennedy’s life and death form “one of the great American stories.” Caro should know. His epic biography of Lyndon B. Johnson brilliantly captures parts of the Kennedy saga, especially the assassination in Dallas, revisited in the latest installment, “The Passage of Power.”

Robert Dallek, the author of “An Unfinished Life,” probably the best single-volume Kennedy biography, suggests that the cultish atmosphere surrounding, and perhaps smothering the actual man may be the reason for the deficit of good writing about him. “The mass audience has turned Kennedy into a celebrity, so historians are not really impressed by him,” Dallek told me. His own book included a good deal of fresh information on Kennedy’s severe health problems and their cover-up by those closest to him. Dallek is also good on the fairy-tale aspects of the Kennedy family history, and he closely examines the workings of the Kennedy White House. Indeed, a dolorous mood of “what might have been” hangs over a good deal of writing about Kennedy. Arriving in time for November 22 was the aptly titled “If Kennedy Lived. The First and Second Terms of President John F. Kennedy: An Alternate History,” by the television commentator Jeff Greenfield, who imagines a completed first Kennedy term and then a second. This isn’t new territory for Greenfield, who worked for Kennedy’s brother Robert and is the author of a previous book of presidential “what ifs” called “Then Everything Changed.”

Thurston Clarke, the author of two previous and quite serviceable books on the Kennedys, also dwells on fanciful “what might have beens” in “JFK’s Last Hundred Days,” suggesting that the death of the presidential couple’s last child, Patrick, brought the grieving parents closer together and may have signaled the end of Kennedy’s compulsive womanizing. What’s more, Clarke makes a giant leap about Kennedy as leader, arguing that in the final 100 days he was becoming a great president. One example, according to Clarke, was his persuading the conservative Republicans Charles Halleck, the House minority leader, and Everett Dirksen, the Senate minority leader, to support a civil rights bill. Once re-elected, Kennedy would have pushed the bill through Congress. Bad books by celebrity authors shouldn’t surprise us, even when the subject is an American president. The true mystery in Kennedy’s case is why, 50 years after his death, highly accomplished writers seem unable to fix him on the page.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who wrote three magisterial volumes on Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, attempted a similar history in “A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House.” Published in 1965, it has the virtues of immediacy, since Schlesinger, Kennedy’s Harvard contemporary, had been on the White House staff, brought in as court historian. He witnessed many of the events he describes. In 1993, the political journalist Richard Reeves wrote “President Kennedy: Profile of Power”, a minutely detailed chronicle of the Kennedy's White House. As a primer on Kennedy’s decision-making, like his handling of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban missile crisis, the book is fascinating. What’s missing is a picture of Kennedy’s personal life, though Reeves includes a passing mention of Marilyn Monroe being sewn into the $5,000 flesh-colored, skintight dress she wore to celebrate the president’s birthday at Madison Square Garden in 1962.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who wrote three magisterial volumes on Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, attempted a similar history in “A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House.” Published in 1965, it has the virtues of immediacy, since Schlesinger, Kennedy’s Harvard contemporary, had been on the White House staff, brought in as court historian. He witnessed many of the events he describes. In 1993, the political journalist Richard Reeves wrote “President Kennedy: Profile of Power”, a minutely detailed chronicle of the Kennedy's White House. As a primer on Kennedy’s decision-making, like his handling of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban missile crisis, the book is fascinating. What’s missing is a picture of Kennedy’s personal life, though Reeves includes a passing mention of Marilyn Monroe being sewn into the $5,000 flesh-colored, skintight dress she wore to celebrate the president’s birthday at Madison Square Garden in 1962.

Balancing out, or warring with, the Kennedy claque are the Kennedy haters, like Seymour M. Hersh and Garry Wills. In “The Dark Side of Camelot,” Hersh wildly posits dubious connections between the Kennedys and the mob. The sum total of this oddly polarized literature is a kind of void. Other presidents, good and bad, have been served well by biographers and historians. We have first-rate books on Jefferson, on Lincoln, on Wilson, on both Roosevelts. Even unloved presidents have received major books: Lyndon B Johnson (Caro) and Richard Nixon (Wills). Kennedy, the odd man out, still seeks his true biographer. Why is this the case? One reason is that even during his lifetime, Kennedy defeated or outwitted the most powerfully analytic and intuitive minds. In November 1960, Esquire magazine commissioned Norman Mailer’s first major piece of political journalism, asking him to report on the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles that nominated Kennedy. Mailer’s long virtuoso article, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” came as close as any book or essay ever has to capturing Kennedy’s essence, though that essence, Mailer candidly acknowledged, was enigmatic.

Here was a 43-year-old man whose irony and grace were keyed to the national temper in 1960. Kennedy’s presence and light was at once soothing and disruptive. He carried himself “with a cool grace which seemed indifferent to applause, his manner somehow similar to the poise of a fine boxer, quick with his hands, neat in his timing, and two feet away from his corner when the bell ended the round.” Finally, however, “there was an elusive detachment to everything he did. One did not have the feeling of a man present in the room with all his weight and all his mind.” Mailer himself doesn’t know “whether to admire this elusiveness, or to beware of it. One could be witnessing the fortitude of a superior sensitivity or the detachment of a man who was not quite real to himself.” And yet Kennedy’s unreality, in Mailer’s view, may have answered the particular craving of a particular historical moment. “It was a hero America needed, a hero central to his time, a man whose personality might suggest contradiction and mysteries which could reach into the alienated circuits of the underground, because only a hero can capture the secret imagination of a people, and so be good for the vitality of his nation.”

Those words seemed to prophesy the Kennedy mystique that was to come, reinforced by the whisker-thin victory over Nixon in the general election, by the romantic excitements of Camelot and then by the horror of Dallas. Over fifty years later we are still sifting through the facts of the assassination. Among the more ambitious is “A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination,” a work of more than 500 pages. Its author, Philip Shenon, a former New York Times reporter, uncovered a new lead, in the person of a heretofore overlooked woman who may have had suspicious ties to Lee Harvey Oswald. But when Shenon finds the woman, now in her 70s, in Mexico, she denies having had a relationship with Oswald, and Shenon’s encounters with her prove more mysterious than illuminating. Kennedy’s murder was bound to attract novelists, and some have approached the subject inventively, if with strange results. Stephen King’s “11/22/63,” a best seller published in 2011, takes the form of a time-travel romp involving a high school English teacher who finds romance in Texas while keeping tabs on Oswald. At more than 800 pages, the novel demands a commitment that exceeds its entertainment value. Most critics seem to think the outstanding example of Kennedy assassination fiction is “Libra,” Don DeLillo’s postmodern novel, published in 1988. The narrative is indeed taut and bracing. But the challenge DeLillo set for himself, to provide readers with “a way of thinking about the assassination without being constrained by half-facts or overwhelmed by possibilities, by the tide of speculation that widens with the years,” exceeds even his lavish gifts.

Here was a 43-year-old man whose irony and grace were keyed to the national temper in 1960. Kennedy’s presence and light was at once soothing and disruptive. He carried himself “with a cool grace which seemed indifferent to applause, his manner somehow similar to the poise of a fine boxer, quick with his hands, neat in his timing, and two feet away from his corner when the bell ended the round.” Finally, however, “there was an elusive detachment to everything he did. One did not have the feeling of a man present in the room with all his weight and all his mind.” Mailer himself doesn’t know “whether to admire this elusiveness, or to beware of it. One could be witnessing the fortitude of a superior sensitivity or the detachment of a man who was not quite real to himself.” And yet Kennedy’s unreality, in Mailer’s view, may have answered the particular craving of a particular historical moment. “It was a hero America needed, a hero central to his time, a man whose personality might suggest contradiction and mysteries which could reach into the alienated circuits of the underground, because only a hero can capture the secret imagination of a people, and so be good for the vitality of his nation.”

Those words seemed to prophesy the Kennedy mystique that was to come, reinforced by the whisker-thin victory over Nixon in the general election, by the romantic excitements of Camelot and then by the horror of Dallas. Over fifty years later we are still sifting through the facts of the assassination. Among the more ambitious is “A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination,” a work of more than 500 pages. Its author, Philip Shenon, a former New York Times reporter, uncovered a new lead, in the person of a heretofore overlooked woman who may have had suspicious ties to Lee Harvey Oswald. But when Shenon finds the woman, now in her 70s, in Mexico, she denies having had a relationship with Oswald, and Shenon’s encounters with her prove more mysterious than illuminating. Kennedy’s murder was bound to attract novelists, and some have approached the subject inventively, if with strange results. Stephen King’s “11/22/63,” a best seller published in 2011, takes the form of a time-travel romp involving a high school English teacher who finds romance in Texas while keeping tabs on Oswald. At more than 800 pages, the novel demands a commitment that exceeds its entertainment value. Most critics seem to think the outstanding example of Kennedy assassination fiction is “Libra,” Don DeLillo’s postmodern novel, published in 1988. The narrative is indeed taut and bracing. But the challenge DeLillo set for himself, to provide readers with “a way of thinking about the assassination without being constrained by half-facts or overwhelmed by possibilities, by the tide of speculation that widens with the years,” exceeds even his lavish gifts.

Kennedy may have enjoyed the company of writers, but the long history of secrecy and mythmaking has surely contributed to the paucity of good books. In recent years, the protective seal seems to have loosened. The Kennedy family, including Edward Kennedy and his sister Jean Kennedy Smith, gave unfettered access to their father’s papers to David Nasaw, the author of “The Patriarch,” a well-received biography of Joseph P. Kennedy. Caroline Kennedy has been open to the claims of history and was involved in the publication of two books and the release of accompanying tapes. One of them, “Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life With John F. Kennedy,” contains the transcripts of the first lady’s interviews about her husband with Schlesinger, conducted in 1964 but kept secret until 2011. Unfortunately, the tapes of William Manchester’s two five-hour interviews with Jackie Kennedy, who seems to have regretted her frankness, remain under seal at the Kennedy Library until 2067. This is a final sadness for a reader sifting through these many books. Taken together, they tell us all too little about this president, who remains as elusive in death as he was in life. Source: nytimes.com

The House of Kennedy (2020), written by James Patterson and Cynthia Fagen, does something I would have thought no writer could possibly do in 2020. In the long section dealing with JFK, I detected not even the mention of the Vietnam conflict. This is astonishing—for two reasons. First, there have been many important documents released by the National Archives that help define President Kennedy’s intentions and policies in Vietnam. If the authors did not want to read those documents—and it’s pretty clear whoever the team was behind this product did not—then there were books based on those documents that one could consult. Patterson and Fagen did not do that either. How on earth can anyone write any kind of biography of John Kennedy, or description of his presidency, and leave that subject out?

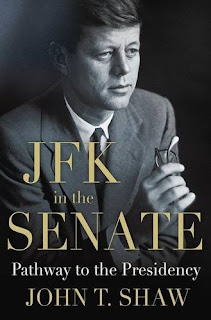

Also, you will not learn anything about what Jack Kennedy did in his 14-year congressional career in this book. That is quite a negative achievement, because author John T. Shaw wrote an entire book about that subject: JFK in the Senate: Pathway to the Presidency (2013). Shaw came to the conclusion that Kennedy’s most important achievement on Capitol Hill was his forging of a new foreign policy toward countries emerging from the bonds of European colonialism. This policy grew directly out of Kennedy’s opposition to what had come before him in the form of both the administrations of Harry Truman and Dean Acheson and that of Dwight Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles. The great schism between Senator John Kennedy and Eisenhower/Dulles came in the form of Kennedy’s famous Algeria speech of 1957. In that speech, the senator denounced the Eisenhower administration’s inability to break away from loyalty to France in the colonial war. John Kennedy said that the White House did not seem to understand that what was going to happen in Algeria was a reprise of what had just happened in 1954 at the siege of Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam. That is a resounding French defeat, with the USA on the wrong side of history again. Source: kennedysandking.com

Jonathan Rosenbaum (The Chicago Reader): "Warren Beatty sounds off angrily and shrewdly about politics, delivering what is possibly his best film and certainly his funniest and liveliest." Bulworth (1998) is a onetime Kennedy liberal (like Beatty himself), an incumbent senator from California who is accused by an opponent of being "old liberal wine trying to pour himself into a new conservative bottle." Distraught because of his own corruption and the sad state of American politics, Bulworth hires an assassin to kill him, an act that gives Beatty a new lease on life. Invigorated, he sets about appropriating African-American slang and culture, as well as telling "the truth." Beatty directed, produced and co-wrote "Bulworth," and it's doubtful that any other Hollywood power could have put a story like this on the screen or would want to. A shrewd political observer for decades, Beatty has fashioned a hilarious morality tale that delivers a surprisingly potent, angry message beneath the laughs. Hollywood rarely embraces political satire on this level as if it were impolite and would make people uncomfortable but Beatty's lampoon excels as sharp commentary.

The coolest stuff in "Bulworth" happens in the second half when the candidate, having decided that he doesn't want to die after all, romances a young black woman (Halle Berry) and hides out at her family's ghetto residence. Beatty deserves huge credit for pulling off an enterprise as audacious and risky as "Bulworth," for giving such a frisky and intelligent performance, and for drawing the best from his supporting actors: Jack Warden as Bulworth's senior aide, Christine Baranski as his brittle wife, Paul Sorvino as a vicious lobbyist, Don Cheadle as a South Central Los Angeles gang leader and especially Oliver Platt as Bulworth's flustered, bellicose chief operative.

You could call him insane, but if you look at it more romantically, perhaps he is "posessed" by the "spirit" of social justice, a mere vessel for the truths that need to be told. He is a character unaware of the significance in what he is saying. To him, if he's not completely insane, he's simply a man who broke down and decided to tell it like it is (ala Peter Finch in Network). There's even a performance by poet-playwright Amiri Baraka as a homeless muse who resurfaces throughout the film to counsel Bulworth, "You got to be a spirit. You got to sing -- don't be no ghost." That piece of poetry may be the closest Beatty comes to a pure statement here: 'Take control of your life,' he seems to say; 'don't let the system play you for a fool.' Nominee for Best Writing in 1999, Screenplay written directly for the screen by Warren Beatty and Jeremy Pikser, Bulworth is a quintessential example of a 'contemporary classic' for our generation. Source: www.sfgate.com

Is JFK a good movie? Actually, it’s a great movie that looks better with each passing year. JFK has a mad genius, making the ultimate point of that Kennedy may have been murdered as part of an institutional coup d’état by powerful shadowy forces, usurping democracy by preventing citizens from investigating further. Stone keeps bringing the movie back to two men. There’s Jim Garrison, whom JFK paints as a fair, reasonable, good-humored man—trying to run a major investigation on a piddly budget, while seeing his faith in institutions tested many times. And then there’s John Kennedy, whom JFK recognizes as a divisive figure, sparking heated arguments among American citizens. “It’s up to you,” Garrison says directly into the camera at the end of the closing argument of the only major criminal trial related to the Kennedy assassination. But as Stone shows the revolting headshot in the Zapruder film, he also reminds the audience that this is a film about a gifted President whose administration ended horrifically—and undemocratically. If Stone hasn’t exactly solved the Kennedy assassination, he has captured—with a dark cinematic flair that leaves you reeling—why it still looms like a sickening nightmare. Source: thedissolve.com

The House of Kennedy (2020), written by James Patterson and Cynthia Fagen, does something I would have thought no writer could possibly do in 2020. In the long section dealing with JFK, I detected not even the mention of the Vietnam conflict. This is astonishing—for two reasons. First, there have been many important documents released by the National Archives that help define President Kennedy’s intentions and policies in Vietnam. If the authors did not want to read those documents—and it’s pretty clear whoever the team was behind this product did not—then there were books based on those documents that one could consult. Patterson and Fagen did not do that either. How on earth can anyone write any kind of biography of John Kennedy, or description of his presidency, and leave that subject out?

Also, you will not learn anything about what Jack Kennedy did in his 14-year congressional career in this book. That is quite a negative achievement, because author John T. Shaw wrote an entire book about that subject: JFK in the Senate: Pathway to the Presidency (2013). Shaw came to the conclusion that Kennedy’s most important achievement on Capitol Hill was his forging of a new foreign policy toward countries emerging from the bonds of European colonialism. This policy grew directly out of Kennedy’s opposition to what had come before him in the form of both the administrations of Harry Truman and Dean Acheson and that of Dwight Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles. The great schism between Senator John Kennedy and Eisenhower/Dulles came in the form of Kennedy’s famous Algeria speech of 1957. In that speech, the senator denounced the Eisenhower administration’s inability to break away from loyalty to France in the colonial war. John Kennedy said that the White House did not seem to understand that what was going to happen in Algeria was a reprise of what had just happened in 1954 at the siege of Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam. That is a resounding French defeat, with the USA on the wrong side of history again. Source: kennedysandking.com

Jonathan Rosenbaum (The Chicago Reader): "Warren Beatty sounds off angrily and shrewdly about politics, delivering what is possibly his best film and certainly his funniest and liveliest." Bulworth (1998) is a onetime Kennedy liberal (like Beatty himself), an incumbent senator from California who is accused by an opponent of being "old liberal wine trying to pour himself into a new conservative bottle." Distraught because of his own corruption and the sad state of American politics, Bulworth hires an assassin to kill him, an act that gives Beatty a new lease on life. Invigorated, he sets about appropriating African-American slang and culture, as well as telling "the truth." Beatty directed, produced and co-wrote "Bulworth," and it's doubtful that any other Hollywood power could have put a story like this on the screen or would want to. A shrewd political observer for decades, Beatty has fashioned a hilarious morality tale that delivers a surprisingly potent, angry message beneath the laughs. Hollywood rarely embraces political satire on this level as if it were impolite and would make people uncomfortable but Beatty's lampoon excels as sharp commentary.

The coolest stuff in "Bulworth" happens in the second half when the candidate, having decided that he doesn't want to die after all, romances a young black woman (Halle Berry) and hides out at her family's ghetto residence. Beatty deserves huge credit for pulling off an enterprise as audacious and risky as "Bulworth," for giving such a frisky and intelligent performance, and for drawing the best from his supporting actors: Jack Warden as Bulworth's senior aide, Christine Baranski as his brittle wife, Paul Sorvino as a vicious lobbyist, Don Cheadle as a South Central Los Angeles gang leader and especially Oliver Platt as Bulworth's flustered, bellicose chief operative.

You could call him insane, but if you look at it more romantically, perhaps he is "posessed" by the "spirit" of social justice, a mere vessel for the truths that need to be told. He is a character unaware of the significance in what he is saying. To him, if he's not completely insane, he's simply a man who broke down and decided to tell it like it is (ala Peter Finch in Network). There's even a performance by poet-playwright Amiri Baraka as a homeless muse who resurfaces throughout the film to counsel Bulworth, "You got to be a spirit. You got to sing -- don't be no ghost." That piece of poetry may be the closest Beatty comes to a pure statement here: 'Take control of your life,' he seems to say; 'don't let the system play you for a fool.' Nominee for Best Writing in 1999, Screenplay written directly for the screen by Warren Beatty and Jeremy Pikser, Bulworth is a quintessential example of a 'contemporary classic' for our generation. Source: www.sfgate.com

Is JFK a good movie? Actually, it’s a great movie that looks better with each passing year. JFK has a mad genius, making the ultimate point of that Kennedy may have been murdered as part of an institutional coup d’état by powerful shadowy forces, usurping democracy by preventing citizens from investigating further. Stone keeps bringing the movie back to two men. There’s Jim Garrison, whom JFK paints as a fair, reasonable, good-humored man—trying to run a major investigation on a piddly budget, while seeing his faith in institutions tested many times. And then there’s John Kennedy, whom JFK recognizes as a divisive figure, sparking heated arguments among American citizens. “It’s up to you,” Garrison says directly into the camera at the end of the closing argument of the only major criminal trial related to the Kennedy assassination. But as Stone shows the revolting headshot in the Zapruder film, he also reminds the audience that this is a film about a gifted President whose administration ended horrifically—and undemocratically. If Stone hasn’t exactly solved the Kennedy assassination, he has captured—with a dark cinematic flair that leaves you reeling—why it still looms like a sickening nightmare. Source: thedissolve.com