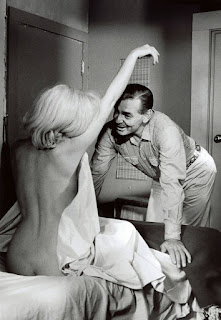

On March 15, 1956, principal photography on Bus Stop began on location in Phoenix. The work Marilyn had done the previous year at the Actors Studio with Strasberg did make her a better actress, as was revealed in this movie. Everything about her as Cherie comes across as genuine and touching, from the way her body slumps exhaustedly in a chair to the exasperation and anger she displays when Bo pushes her around. But this new depth in Marilyn’s acting came at a price. Now there were demons on the set—her own demons that she called up from her past to use in her acting. The past was with her constantly now—and the pressures she put herself under were worse than ever. “She was the most nervous actor I’d ever worked with,” Don Murray said. “She would break out into hives and her body would be covered with little red splotches, and they’d have to cover up with makeup.”

During the production of Bus Stop, a young publicist named Patricia “Pat” Newcomb was assigned to handle Marilyn’s press and would briefly enter Marilyn’s inner circle. A few years later Newcomb would become one of the major players in the last months of Marilyn’s life. Newcomb was young, smart, and fiercely loyal to her celebrity clients. She was also known to have a volatile temper—she would slam her office door so hard that a framed picture of Dean Martin would fall off the wall, shattering the glass “every other day.” Rupert Allan, who handled most of Marilyn’s press relations, told biographer Donald Spoto that Pat Newcomb would take phone messages for Marilyn—many from men wanting to meet her. “Pat intercepted Marilyn’s messages,” Allan said. Then, according to Allan, things went too far. Newcomb didn’t particularly look like Marilyn, but perhaps with the right lighting and makeup she could pass for some unfamiliar people.

Fred Lawrence Guiles wrote in his biography, “Patricia Newcomb was a twenty-five-year-old Mills College graduate who resembled Marilyn physically. They were almost exactly the same height (almost five feet six); her thick hair was medium blond and hung loose to her shoulders.” Rupert Allan asserted that Newcomb went through “a lesbian phase” but also dated men. Marilyn protested about Pat, ‘She’s not Marilyn!’” It would be nearly five years before she and Marilyn would be in contact again. And at that time Newcomb would become one of the most important and controversial people in Marilyn’s life—known as the keeper of her secrets and one of the last people to see Marilyn on the day she died. The head of Marilyn’s public relations firm, Arthur Jacobs, recommended she give Newcomb another try. Newcomb entered Marilyn’s life again, but this time the two would work well together and become close. Those who knew Marilyn well in her last years say that the two women would become extraordinarily close. Rupert Allan and Ralph Roberts (among others) would come to believe that Pat Newcomb became obsessed with Marilyn as she became more and more a part of her famous client’s life.

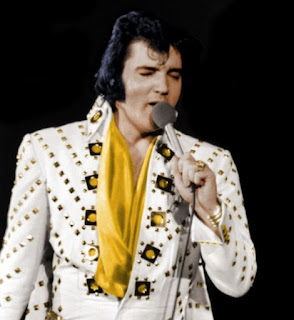

On November 16, 1960, Marilyn was awoken by the phone and, in her half-sleep state, was informed that Clark Gable had died. He died of a coronary thrombosis while recuperating in the hospital from a heart attack. In childhood she had fantasized that Gable was her father. He behaved tenderly and protectively toward her during the harrowing months they spent making The Misfits. Now she had lost another connection to a father figure. Marilyn was overwhelmed with despair. To make matters worse, she worried that perhaps her frustrating absences during the shooting had contributed to Gable’s death. His widow made statements to the press suggesting that the maddening delays in making The Misfits had contributed to his heart attack. Kay Gable never mentioned Marilyn by name, but the implication seemed clear: “That picture helped kill my husband. It wasn’t the physical exertion that did it; it was the horrible tension—that eternal waiting. He waited around forever, for everybody. He’d get so angry waiting.”

Marilyn spent Christmas Eve quietly in her apartment with her new public relations agent, Pat Newcomb. For a present, Marilyn gave Newcomb a mink coat. It was an extravagant gift for a recent employee—and someone she had clashed with and mistrusted in the past. Perhaps it was Marilyn’s way of saying she had been wrong about her initial impression. That evening, however, she received a “forest of poinsettias” from Joe DiMaggio. She invited him to visit her, and they did spend Christmas night alone together. They quietly began seeing each other again. Always very discreet, DiMaggio would visit her at her apartment. He would arrive late in the evening, use the service elevator, enter through the kitchen door, and leave by dawn. DiMaggio remained concerned not only at the apparent wasteland of Marilyn’s emotional life but her increasingly haggard appearance. The release of The Misfits also devastated her. Before its premiere she had tremendous hopes that this performance might be the start of a turning point in her career. So much effort had gone into it and had backfired. Bosley Crowther, in the all-important New York Times, said: “Miss Monroe—well, she is completely blank and unfathomable as a new divorcée. There is really not much about her that is very exciting or interesting.” Despite a few excellent reviews, the critics’ opinions leaned toward the negative. Now Marilyn’s dreams of being taken seriously as an actress seemed as far away as ever. She had let down the Strasbergs. She had let down her fans. She had let down herself.

Fox announced that they planned to cast her in the lead of Goodbye Charlie, by George Axelrod, which had been a Broadway flop starring Lauren Bacall. The plot revolved around a callous playboy, Charlie, who is killed by a lover’s jealous husband and instantly reincarnated in the body of a gorgeous woman—to be played by Marilyn. Although Charlie materializes in glorious female form, his/her mind and mannerisms remain those of a male. The studio was eager to collect the last picture Marilyn owed them on her contract and thought the novelty of Marilyn Monroe playing a man trapped inside her famous curves would be a box-office bonanza. Marilyn, however, was appalled at the idea of having to butch it up. She couldn’t bear the thought of her femininity being questioned. Obsessing over homosexuality during a psychiatric session with Greenson, Marilyn had expressed rage when he informed her that there was something feminine and masculine in both genders, and she became mortified that anything masculine might be perceived in her. Now she was being asked to act masculine on screen for laughs. “The studio people want me to do Goodbye Charlie,” she fumed to the press. “But I’m not going to do it. I don’t like the idea of playing a man in a woman’s body.” George Cukor claimed that she could not be directed: “You couldn’t reach her, she was like underwater.” Her clash with director Cukor during the filming of Something's Gotta Give could be attributed to her difficulties about connecting with a gay director. But Monroe had acted this way with other directors she deemed unsympathetic.

“It’s Pat Newcomb who knows more about Marilyn Monroe than anyone else,” Jeanne Martin (Dean Martin’s wife) commented once. In Monroe biographies, the shadowy Pat Newcomb often comes across as being a not very forthcoming person, mostly because of her silences and dodges when it comes to discussing Marilyn in her very few interviews. Newcomb and Marilyn had psychological traits in common. Jeanne, who socialized with both women, observed that Newcomb, like Marilyn, “had highs and lows.” Both of them used prescription drugs, especially sedatives. Both women relied heavily on their psychiatrists. Newcomb was at Marilyn’s side at almost every major event in 1961–62, hovering protectively on the sidelines. When not working, the two women socialized together, and it was through Newcomb that Marilyn reacquainted herself with Peter Lawford and his wife, Pat Kennedy Lawford, the sister of John and Bobby Kennedy. Newcomb would often stay at Marilyn’s apartment when she was in New York and—at times—at her home in Los Angeles. People who were around at the time go so far as to say that Newcomb became obsessed with Marilyn.

Because of Newcomb’s feverish dedication to Marilyn, her intentions began to confuse the star. Marilyn both craved this devotion and feared it. Some say Newcomb wanted more from Marilyn than she was prepared to give. But—at this stage in her life—without a husband or steady lover, Marilyn needed someone who extended complete dedication, unconditional love. This is what Newcomb offered. In return—as she did with anyone who was devoted to her—Marilyn made extreme demands. If Marilyn tried to call Newcomb at home and got a busy signal, she would become hysterical. When she finally got through she would scream and yell. Eventually Marilyn had a separate phone line installed in Newcomb’s apartment so she could reach her at all times. As always, Marilyn would do her best to repay Newcomb’s loyalty. After she complained that her car wasn’t working well, Marilyn gave Newcomb a new Thunderbird. And after wearing them a few times, Marilyn gave Pat a valuable pair of emerald earrings Frank Sinatra had given her. But after Marilyn’s death, Newcomb seemed to want to distance herself from their intensely personal and multilayered relationship. In spite of what Newcomb had to say, all the evidence shows that she and Marilyn were very close. When Newcomb suggested Rupert Allan he should go through her—instead of contacting Marilyn directly—Allan snapped back that he had been a friend of Marilyn’s for a long time. Michael Selsman, who also worked with Newcomb at the Arthur P. Jacobs agency, claims that there was a lot of talk about a possible lesbian relationship between Marilyn and Newcomb—and it wasn’t coming from the show-business community. The rumors spread among people in Marilyn’s circle “who knew her and worked with her.”

“Pat Newcomb was the closest confidante to Marilyn,” Milt Ebbins, Peter Lawford’s agent and friend, who was part of Marilyn’s social set, commented. “Was there something sexual between them? I have no proof of that, but they were very close. Constantly together. Marilyn loved her, she was very fond of her.” Susan Strasberg pointed out that “the adrenaline rush that came from Marilyn’s involvement with Pat Newcomb became somewhat sexualized.” Strasberg would say that Marilyn had nicknamed Newcomb “Sybil,” implying friendly “sibling rivalry.” But as their relationship intensified, Marilyn’s feelings grew more complicated, with paranoid undertones. For her there was a clear line of masculine and feminine behavior, and the confusing of genres terrified her. She was paranoid about finding anything masculine in herself. Marilyn began discussing Newcomb in her sessions with Dr. Greenson, with homosexuality a major concern. “She could not bear the slightest hint of anything homosexual,” Greenson wrote. “She had an outright phobia of homosexuality and yet unwittingly fell into situations which had homosexual coloring, which she then recognized and projected onto the other, who then became her enemy.”

“Marilyn’s mother was schizophrenic,” Susan Strasberg observed. “As a result Marilyn’s feelings toward women were complex and ambivalent.” In his correspondence Greenson gave an example of Marilyn’s relationship with a girlfriend named “Pat,” who had put a blond streak in her hair, close to Marilyn’s color. Marilyn interpreted Newcomb’s emulation as an attempt to “take possession of her,” feeling that identification meant “homosexual possessiveness.” Greenson wrote that Marilyn “burned with fury against this girl,” accusing her of trying to “rob her most valuable possession.” So much of Marilyn’s identity, her public persona, was being the sexual desire of men. Her whole projection of herself was based on that. Newcomb’s perceived passionate feelings threatened her. But—with everything in her life becoming more confusing and unclear—she pressed ahead with the relationship. “She could be very touching,” Newcomb recalled. “I always felt a kind of watching out for her. But deep down at the core she was really strong. And you’d forget it because she seemed so vulnerable.” Sometimes Marilyn’s suppressed angst surfaced, and she would say something “quite cruel,” Newcomb revealed. “She could be quite mean.” Newcomb declined all offers to publish a memoir of her time with Marilyn. This may seem an odd stance for a woman whose entire career has been devoted to maintaining the public image of Marilyn Monroe. She only gave interviews to Donald Spoto, Anthony Summers, Lois Banner and Gary Vitacco-Robles.

“Marilyn’s vocabulary included words I’d never ever heard of, and she wielded them like a sailor with no embarrassment,” Susan Strasberg once said. “She had quite a temper when she lost control.” As the months went on, Marilyn’s love-hate relationship with Newcomb would grow more extreme. It would crescendo on the last mysterious day of Marilyn’s life. In mid-June 1962, Marilyn entered a hypomanic phase of activity, socializing and publicizing herself. To combat the ongoing negative publicity of her dismissal from Something’s Got to Give, Marilyn had Newcomb set up in-depth interviews with Redbook and LIFE. Marilyn also agreed to a photo layout for Cosmopolitan. Marilyn was desperately trying to convince the public—and herself—that she was more than a sex symbol. The amount of medication Marilyn was taking cannot be overlooked. Greenson’s family said that he was trying to wean Marilyn from her dependency on Nembutal by prescribing chloral hydrate, a sedative he felt was not as addictive. Newcomb admitted that she and Marilyn shared pills at times. “One time I just wanted to relax, and there wasn’t valium and she gave me a pill and I was knocked out,” Newcomb said. “I was so detached. I was scared.”

On Friday afternoon, August 3, 1962, Marilyn filled two prescriptions at a pharmacy on Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills. One was for Phenergan, a drug used to treat allergies, and the other for Nembutal. Greenson and Engelberg had been weaning Marilyn off of Nembutal for weeks, substituting the milder drug chloral hydrate. Marilyn would take that with a glass of milk before bed. That evening Pat Newcomb had dinner with Marilyn in a Santa Monica French restaurant, whose name she can’t remember. When talking to Donald Spoto she said, “Afterwards we came back to the house. We just sat around—” Then Newcomb indicated the journalist’s tape recorder, stating, “I want to shut this off.” On Saturday, August 4, 1962, Mrs. Murray found Marilyn quiet and contemplative. She had tentative plans of going to Peter Lawford’s house for dinner in the evening. Some say that Robert Kennedy had planned to make a quick trip from San Francisco to attend the party, specifically to talk to Marilyn. Legend has come down through the years that Marilyn’s foul mood toward Newcomb was because she had been able to sleep for twelve hours straight while Marilyn slept very little. That’s probably partially true. However, there was something else going on that Pat Newcomb has been silent about for decades. Many years later Milt Ebbins evasively said that Newcomb was party to many secret things regarding Marilyn in her last months.

The reason for Marilyn’s fury the last days of her life is that she had come to believe that Pat Newcomb had become romantically involved with Bobby Kennedy—an involvement that would have overlapped with the time frame in which Marilyn had been seeing him. We can only imagine Marilyn’s rage and confusion. Bobby’s desire for her, his love for her, is what was going to make the thirty-six-year-old love goddess feel relevant again. Pat Newcomb was an attractive, sexy, intelligent woman who was four years younger than her. But she wasn’t Marilyn Monroe. If Bobby did have an intimate entanglement with Marilyn’s assistant/press agent while Marilyn was relying on his affection, she must have felt worthless. It was Newcomb, along with Peter Lawford, who had gotten Marilyn involved with the Kennedys in the first place. Now Marilyn felt betrayed by someone she considered a trustworthy friend. She had been demanding explanations and details about the affair from Newcomb all week. Newcomb did admit that she saw Bobby Kennedy shortly before Marilyn died. She could not remember the exact evening but revealed: “I had dinner with him, but it was just before that night.” When you’re fragile, empty, and lonely—as Marilyn was that summer—any slight or rejection becomes amplified. It can feel fatal. It can feel like The End. —"Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon" (2018) by Charles Casillo

In December 1961 Marilyn's psychiatrist Dr. Ralph Greenson labeled her a 'borderline paranoid schizophrenic' in a letter sent to Anna Freud. Rather than work in a vacuum, Dr. Greenson obtained a second opinion by consulting psychologist Dr. Milton Wexler. After taking a doctorate at Columbia University, studying under Theodor Reik, a disciple of Freud, he became one of the country’s first nonphysicians to set up in practice as a psychoanalyst. Also a member of the Los Angeles Psychoanalytic Society, Dr. Wexler would go on to become a pioneer in the study and treatment of Huntington’s disease, forming the Hereditary Disease Foundation. Wexler also felt strongly that Marilyn Monroe suffered at least from borderline paranoid schizophrenia after sitting in on three sessions with her at Dr. Greenson’s home. “Yes, I treated her,” he said in 1999. “I will say that I agreed with Dr. Greenson that she presented borderline symptoms of the disease that had run in her family. I found her to be very proactive in wanting to treat those borderline symptoms, as well. One misconception about her treatment is that it was Dr. Greenson’s idea that she move in with his family. She never moved in with the Greensons. Instead, it was my suggestion that she spend as much time there as possible in order to create the environment that she lacked as a child. That was my theory at the time and Dr. Greenson agreed.” To ignore the findings of these two doctors makes no sense all of these many years later. However dominant, “Marilyn Monroe” was only one persona among many that emerged from and were created by the original Norma Jeane Baker. —"The Secret Life of Marilyn Monroe" (2009) by J. Randy Taraborrelli