American Sniper has set its sights on another record: Within a matter of days, it will overtake Steven Spielberg's WWII classic Saving Private Ryan to become the top-grossing war-themed film of all time in North America, not accounting for inflation. Clint Eastwood's history-making movie jumped the $200 million mark on Sunday,

putting it ahead of Michael Bay's Pearl Harbor, another WWII title, which topped out at $198.5 million domestically in 2001. American Sniper is distinct from those two film in being set during a modern-day conflict.

Saving Private Ryan, released in 1998, earned $216.7 million domestically. Taking inflation into account, that would equal roughly $312 million in today's terms. But a record is a record, and the history-making Sniper will cross $216 million sometime this week for Warner Bros. and Village Roadshow.

American Sniper is benefiting from a massive turnout in America's heartland, as well as from its six Oscar nominations, including best picture and best actor for Bradley Cooper's performance as the late Chris Kyle, a Navy SEAL who fought in the second Iraq war. In celebrating Sniper's $200 million milestone, Warners domestic distribution chief Dan Fellman said that Eastwood "created a gripping drama with a rare insight into the toll of war that has resonated with audiences in almost every demographic." Here's a rundown of how films addressing post-9/11 conflicts, or terrorism, have performed, according to Rentrak:

Lone Survivor

Release: 12/25/13

Rating: R

Gross: $125,088,651

Zero Dark Thirty

Release: 12/19/12

Rating: R

Gross: $95,720,716

Act of Valor

Release: 2/24/12

Rating: R

Gross: $70,012,847

Jarhead

Release: 11/4/05

Rating: R

Gross: $62,696,152

The Kingdom

Release: 9/28/07

Rating: R

Gross: $47,536,778

Green Zone

Release: 3/12/10

Rating: R

Gross: $35,497,337

The Hurt Locker

Release: 6/26/09

Rating: R

Gross: $17,017,811

Source: www.hollywoodreporter.com

On stage, Bradley Cooper plays Joseph Merrick, a disfigured man whose life story has been made into multiple theatre productions and a film. It is reported that the actor will next be heading to London for another run of The Elephant Man after it wraps on Broadway. While in New York Bradley has made a ritual of taking the subway to rehearsals and performances on a regular basis. But as he continues to enjoy public transport his career has taken off with not only an Oscar nod for his performance in American Sniper but also box office success. The total haul for American Sniper, which is up for six Academy Awards, stands at $200.4 million. Source: www.dailymail.co.uk

Bradley Cooper in Vanity Fair magazine, January 2015

A video featuring pictures of Bradley Cooper, his co-stars Jennifer Lawrence, Amy Adams, Sienna Miller, girlfriend Suki Waterhouse, etc., and scenes from "American Sniper".

Friday, January 30, 2015

Tuesday, January 27, 2015

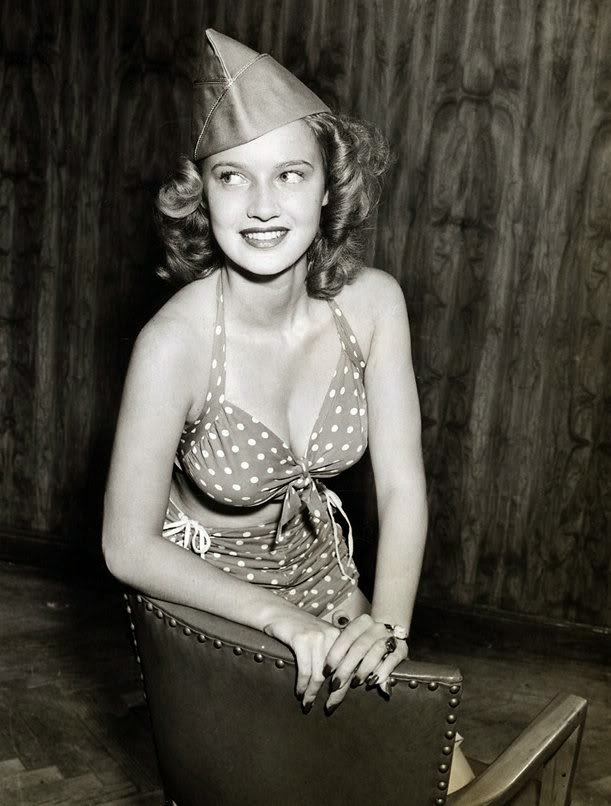

Donna Reed's Anniversary, World War II's Hollywood Pin-Ups

Happy Anniversary, Donna Reed!

"Forty pictures I was in, and all I remember is 'What kind of bra will you be wearing today, honey?' That was always the area of big decision - from the neck to the navel." -Donna Reed

They gave Donna Reed the best supporting actress Oscar (Sinatra got supporting actor, too), and so they should have. But there she was in this scene, there was Donna Reed, gazing into the depths of life with shocking bleakness and talking about how one day she’d go home and get married and join the country club and do all the “proper” things for the “proper” people.

The scene jumped out of the picture—how did Lorene and the lovely, sweet Donna Reed get all that self-loathing and contempt on screen? Well, maybe she was more interesting than anyone guessed. I looked the picture up in the collected reviews of Manny Farber and, wouldn’t you know it, he said this in The Nation in 1953: “Miss Reed… is an interesting actress whenever Cameraman Burnett Guffey uses a hard light on her somewhat bitter features.”

In truth, the scene is better than Farber suggests, and it leaves Montgomery Clift’s Prewitt (the self-conscious emotional heart of the picture) somewhat at a loss. Because Reed’s face has seen a truth that exceeds the rest of From Here to Eternity. In addition, the film was boldly cast: Deborah Kerr (it was going to be Joan Crawford) is a surprise as the disillusioned wife, Karen; Burt Lancaster is subtle as Sergeant Warden; Clift is Clift; and then, there was Frank Sinatra, who knew this was his title shot and wasn’t going to let it get away. -David Thomson

Maggio (Frank Sinatra) busts in on Prewitt (Montgomery Clift) and Loreen (Donna Reed) as they try to get to know each other in this scene from FROM HERE TO ETERNITY.

World War II pinups appeared in many forms, from fighter and bomber nose art and bomber jacket art to calendars, postcards, matchbooks, and playing cards. The term pinup was coined during World War II, when soldiers would "pin up" these idealized pictures on their barracks and foxhole walls, and sailors did the same to lockers and bulkheads. There were photos of Betty Grable and Rita Hayworth and Lana Turner, and hundreds of other calendar girls and Hollywood starlets whose only claim to fleeting fame was their image seared into a GI's brain from a ragged page of YANK or Esquire magazine. Servicemen soon began to create their own pinup art, decorating the noses of their planes and their bomber jackets with more primitive paintings of shapely babes. Source: www.skylighters.org

Servicemen would purchase such publications as Yank — the soldier’s magazine — which proudly displayed centerfolds of lovely young women in seductive poses, typically adorned in bathing suits, which the boys would “pin-up” on their barracks walls. However, prior to World War II and before the age of the photographic lens, soldiers and fighting men didn’t possess the luxury of hording an eight-byten image of their idol. Established stars such as Myrna Loy and Ida Lupino would hand out sandwiches at the Hollywood Canteen to soldiers on blackout assignments.

Penny Singleton, the pin-up girl of the Marine Corps — she was married to a Marine captain — established an alterations and repair community for the servicemen, which she called the “Sew and Sew Club.” The fair-haired actress, best known as the lead in the many Blondie pictures, enlisted a number of Hollywood personalities to assist her in this free-for-the-troops endeavor.

Such alluring cheesecake models as Marlene Dietrich, Jinx Falkenburg, Candy Jones, and Carole Landis entertained troops in foreign settings, and the troops were eternally grateful for their sacrifice. Little meant more to the American fighting man than to know that the ladies had them uppermost on their minds. To be greeted by a pin-up girl and given a fond farewell by her, before departure into war, was a gesture of profound magnitude. Linda Darnell, although a stunning pin-up girl whose beauty was out-of-this-world, enlisted in the Women’s Ambulance and Defense Corps of America and even took lessons on motor vehicle repair in her spare time.

Veronica Lake acquired over fifty sets of wings from cadets on one junket, as admiring gents surely wanted to pin their brass wings on the stunning Miss Lake’s dress. The wearing of military paraphernalia by pin-up girls became a common practice, for the gals showed the men in the armed forces that their simple little admiring gifts did not go unnoticed or unappreciated. -"The Pin-Up Girls of World War II" (2013) by Brett Kiser

US and British military culture in World War II promoted this preoccupation with sex. Over 5 million copies of Life magazine’s 1941 photo of Rita Hayworth (captioned the “Goddess of Love”) were sent out to US soldiers. Such “pin-ups” were ubiquitous among US forces. They were published not only in men’s magazines but in service publications like Stars and Stripes (or for Britain, Reveille).

The appeal of the “undisputed leader,” Betty Grable, “was less erotic than as a wholesome symbol of American womanhood,” based on a “carefully groomed exploitation of her good-natured hominess by 20th Century-Fox.” Hayworth, however, the “runner-up” to Grable, “exuded the sultry sex appeal of a mature woman” whose “appeal was more erotic than wholesome.”

Jane Russell’s “flamboyant sex appeal made her pin-ups wildly popular with GIs overseas.” Her large breasts were shamelessly exploited by movie producers as “the two great reasons for [her] rise to stardom.” Moralists at home opposed the pin-up craze. In 1944, the Postmaster General banned Esquire with its Vargas Girl fantasies, and Congressional hearings ensued. However, officers decided that pin-ups contributed to soldiers’ morale. In Britain, meanwhile, the cartoon heroine “Jane” boosted morale during the Blitz and thereafter by taking her clothes off during periods of bad news. “It was said that the first armored vehicle ashore on D-Day carried a large representation of naked Jane.” The comic-strip Jane “finally lost the last vestiges of her modesty during the Normandy campaign” in 1944, and soldiers said, “Jane gives her all.”

Behind the lines, by contrast, sex flourished in World War II. By one calculation, the average US soldier who served in Europe from D-Day through the end of the war had sex with 25 women. The peak was reached after the surrender of Germany in 1945. Condoms had to be rationed at four per man per month and medical officers considered this “entirely inadequate.” Over 80 percent of those who had been away over two years admitted to having regular sexual intercourse. In US-occupied Italy, three-quarters of US soldiers had intercourse with Italian women, on average once or twice a month.

War stories that focus on the front rarely discuss sex. For example, historian Stephen Ambrose gives detail-oriented accounts of battles, but only a vague mention that Paris after liberation in 1944 “over the next few days had one of the great parties of the war.” Ambrose mentions that German soldiers in the Battle of the Bulge were motivated by being told that hospitals in Belgium contained “many American nurses.” When the huge bureaucracy of the US Army’s Services of Supply moved to Paris, “a black market on a grand scale sprang up… The supply troops… got the girls, because they had the money, thanks to the black market.” Ambrose can take for granted that “girls” were a commodity in wartime cities. Aside from these occasional references, however, Ambrose bypasses sex, presumably because it does not matter at the front.

By some reports, “war aphrodisia” – common among soldiers in many wars – extended into many segments of society during “total war.” The million and a half US soldiers who filled England before D-Day in 1944 had a well-deserved reputation as “wolves in wolves’ clothing.” They were, in one British phrase of the time, “oversexed, overpaid, and over here.” England’s men were absent in large numbers, and its women had survived blackout and Blitz. The US soldiers’ presence contributed to a shake-up of British sexual mores, already under strain from the war. Back in the United States, “Victory Girls” gave free sex to soldiers as their “patriotic duty.”

The ill-defined “‘victory girl’ was usually assumed to be a woman who pursued sexual relations with servicemen out of a misplaced patriotism or a desire for excitement. She could also, without actually engaging in sexual relations, was testing the perimeters of social freedom in wartime America. According to FBI statistics, the number of women charged with morals violations doubled in the war years. A “surprising number were young married women.” Detroit banned unescorted women from bars after 8 pm. In Germany too, as social control disintegrated at the end of World War II, civilian gender limits expanded. In the Rhineland in 1945, advancing Allied forces found “Edelweiss gangs” of young men in pink shirts and bobby-sox, who “roamed the rubble hurling insults and stones at the Hitler Youth – when they were not trading sexual favors with willing girls.” Source: www.warandgender.com

"Forty pictures I was in, and all I remember is 'What kind of bra will you be wearing today, honey?' That was always the area of big decision - from the neck to the navel." -Donna Reed

They gave Donna Reed the best supporting actress Oscar (Sinatra got supporting actor, too), and so they should have. But there she was in this scene, there was Donna Reed, gazing into the depths of life with shocking bleakness and talking about how one day she’d go home and get married and join the country club and do all the “proper” things for the “proper” people.

The scene jumped out of the picture—how did Lorene and the lovely, sweet Donna Reed get all that self-loathing and contempt on screen? Well, maybe she was more interesting than anyone guessed. I looked the picture up in the collected reviews of Manny Farber and, wouldn’t you know it, he said this in The Nation in 1953: “Miss Reed… is an interesting actress whenever Cameraman Burnett Guffey uses a hard light on her somewhat bitter features.”

In truth, the scene is better than Farber suggests, and it leaves Montgomery Clift’s Prewitt (the self-conscious emotional heart of the picture) somewhat at a loss. Because Reed’s face has seen a truth that exceeds the rest of From Here to Eternity. In addition, the film was boldly cast: Deborah Kerr (it was going to be Joan Crawford) is a surprise as the disillusioned wife, Karen; Burt Lancaster is subtle as Sergeant Warden; Clift is Clift; and then, there was Frank Sinatra, who knew this was his title shot and wasn’t going to let it get away. -David Thomson

Maggio (Frank Sinatra) busts in on Prewitt (Montgomery Clift) and Loreen (Donna Reed) as they try to get to know each other in this scene from FROM HERE TO ETERNITY.

World War II pinups appeared in many forms, from fighter and bomber nose art and bomber jacket art to calendars, postcards, matchbooks, and playing cards. The term pinup was coined during World War II, when soldiers would "pin up" these idealized pictures on their barracks and foxhole walls, and sailors did the same to lockers and bulkheads. There were photos of Betty Grable and Rita Hayworth and Lana Turner, and hundreds of other calendar girls and Hollywood starlets whose only claim to fleeting fame was their image seared into a GI's brain from a ragged page of YANK or Esquire magazine. Servicemen soon began to create their own pinup art, decorating the noses of their planes and their bomber jackets with more primitive paintings of shapely babes. Source: www.skylighters.org

Servicemen would purchase such publications as Yank — the soldier’s magazine — which proudly displayed centerfolds of lovely young women in seductive poses, typically adorned in bathing suits, which the boys would “pin-up” on their barracks walls. However, prior to World War II and before the age of the photographic lens, soldiers and fighting men didn’t possess the luxury of hording an eight-byten image of their idol. Established stars such as Myrna Loy and Ida Lupino would hand out sandwiches at the Hollywood Canteen to soldiers on blackout assignments.

Penny Singleton, the pin-up girl of the Marine Corps — she was married to a Marine captain — established an alterations and repair community for the servicemen, which she called the “Sew and Sew Club.” The fair-haired actress, best known as the lead in the many Blondie pictures, enlisted a number of Hollywood personalities to assist her in this free-for-the-troops endeavor.

Such alluring cheesecake models as Marlene Dietrich, Jinx Falkenburg, Candy Jones, and Carole Landis entertained troops in foreign settings, and the troops were eternally grateful for their sacrifice. Little meant more to the American fighting man than to know that the ladies had them uppermost on their minds. To be greeted by a pin-up girl and given a fond farewell by her, before departure into war, was a gesture of profound magnitude. Linda Darnell, although a stunning pin-up girl whose beauty was out-of-this-world, enlisted in the Women’s Ambulance and Defense Corps of America and even took lessons on motor vehicle repair in her spare time.

Veronica Lake acquired over fifty sets of wings from cadets on one junket, as admiring gents surely wanted to pin their brass wings on the stunning Miss Lake’s dress. The wearing of military paraphernalia by pin-up girls became a common practice, for the gals showed the men in the armed forces that their simple little admiring gifts did not go unnoticed or unappreciated. -"The Pin-Up Girls of World War II" (2013) by Brett Kiser

US and British military culture in World War II promoted this preoccupation with sex. Over 5 million copies of Life magazine’s 1941 photo of Rita Hayworth (captioned the “Goddess of Love”) were sent out to US soldiers. Such “pin-ups” were ubiquitous among US forces. They were published not only in men’s magazines but in service publications like Stars and Stripes (or for Britain, Reveille).

The appeal of the “undisputed leader,” Betty Grable, “was less erotic than as a wholesome symbol of American womanhood,” based on a “carefully groomed exploitation of her good-natured hominess by 20th Century-Fox.” Hayworth, however, the “runner-up” to Grable, “exuded the sultry sex appeal of a mature woman” whose “appeal was more erotic than wholesome.”

Jane Russell’s “flamboyant sex appeal made her pin-ups wildly popular with GIs overseas.” Her large breasts were shamelessly exploited by movie producers as “the two great reasons for [her] rise to stardom.” Moralists at home opposed the pin-up craze. In 1944, the Postmaster General banned Esquire with its Vargas Girl fantasies, and Congressional hearings ensued. However, officers decided that pin-ups contributed to soldiers’ morale. In Britain, meanwhile, the cartoon heroine “Jane” boosted morale during the Blitz and thereafter by taking her clothes off during periods of bad news. “It was said that the first armored vehicle ashore on D-Day carried a large representation of naked Jane.” The comic-strip Jane “finally lost the last vestiges of her modesty during the Normandy campaign” in 1944, and soldiers said, “Jane gives her all.”

Behind the lines, by contrast, sex flourished in World War II. By one calculation, the average US soldier who served in Europe from D-Day through the end of the war had sex with 25 women. The peak was reached after the surrender of Germany in 1945. Condoms had to be rationed at four per man per month and medical officers considered this “entirely inadequate.” Over 80 percent of those who had been away over two years admitted to having regular sexual intercourse. In US-occupied Italy, three-quarters of US soldiers had intercourse with Italian women, on average once or twice a month.

War stories that focus on the front rarely discuss sex. For example, historian Stephen Ambrose gives detail-oriented accounts of battles, but only a vague mention that Paris after liberation in 1944 “over the next few days had one of the great parties of the war.” Ambrose mentions that German soldiers in the Battle of the Bulge were motivated by being told that hospitals in Belgium contained “many American nurses.” When the huge bureaucracy of the US Army’s Services of Supply moved to Paris, “a black market on a grand scale sprang up… The supply troops… got the girls, because they had the money, thanks to the black market.” Ambrose can take for granted that “girls” were a commodity in wartime cities. Aside from these occasional references, however, Ambrose bypasses sex, presumably because it does not matter at the front.

By some reports, “war aphrodisia” – common among soldiers in many wars – extended into many segments of society during “total war.” The million and a half US soldiers who filled England before D-Day in 1944 had a well-deserved reputation as “wolves in wolves’ clothing.” They were, in one British phrase of the time, “oversexed, overpaid, and over here.” England’s men were absent in large numbers, and its women had survived blackout and Blitz. The US soldiers’ presence contributed to a shake-up of British sexual mores, already under strain from the war. Back in the United States, “Victory Girls” gave free sex to soldiers as their “patriotic duty.”

The ill-defined “‘victory girl’ was usually assumed to be a woman who pursued sexual relations with servicemen out of a misplaced patriotism or a desire for excitement. She could also, without actually engaging in sexual relations, was testing the perimeters of social freedom in wartime America. According to FBI statistics, the number of women charged with morals violations doubled in the war years. A “surprising number were young married women.” Detroit banned unescorted women from bars after 8 pm. In Germany too, as social control disintegrated at the end of World War II, civilian gender limits expanded. In the Rhineland in 1945, advancing Allied forces found “Edelweiss gangs” of young men in pink shirts and bobby-sox, who “roamed the rubble hurling insults and stones at the Hitler Youth – when they were not trading sexual favors with willing girls.” Source: www.warandgender.com

Saturday, January 24, 2015

Ann Todd's Anniversary, H. G. Wells, Cornel Woolrich & F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood

Happy Anniversary, Ann Todd!

The Seventh Veil (1945) - British Classic Noir - Full Movie, starring James Mason, Ann Todd, Herbert Lom...The movie begins with Francesca (Ann Todd) in the hospital—mental hospital it’s soon revealed. Recovering from her unsuccessful suicide attempt, she tells her life’s story to psychiatrist Dr. Larsen (Herbert Lom). This is one of those rare films where the psychiatrist doesn’t fall in love with his patient.

She relates going to live with her crippled, pianist guardian, Nicholas, who imperiously turns her piano talents into concert pianist proportions. And she dutifully becomes famous, as a love of music drives her as much as it drives her cousin. Francesca’s first love is an “American” band leader (British actor Hugh McDermott, sans an American accent), but when she informs Nicholas she plans to marry, he decrees otherwise, as he is her guardian until she’s twenty-one. Nicholas commissions him to paint her portrait, which eventually hangs on Nicholas’ wall, á la Gene Tierney’s portrait in Laura, Joanne Woodward’s in Sleuth, Jennifer Jones’ in Portrait of Jennie.

Source: classicfilmfreak.com

The Passionate Friends (1948) - David Lean David Lean's film adaptation of the H. G. Wells story, starring Ann Todd, Trevor Howard and Claude Rains.

Ann Todd plays Sylvia Leeds Kent in "Sylvia" from "Alfred Hitchcock presents" (19 Jan. 1958)

Sylvia is a young woman who we think is contemplating suicide. Her ex-husband, Peter, married her for money. When he forged a check, her father agreed not to prosecute if he divorced her. Now Sylvia is again in touch with Peter, and wants him back. Peter calls her father and tells him that he will stay out of her life for a price. Sylvia's father tells her about his blackmail scheme, and she tells him that she bought a gun to use on Peter if they did not get back together. She goes to her room alone and is followed by her father, who is worried about her and tries to retrieve the gun.

The original "Rear Window" ("It Had to Be Murder", written by Cornell Woolrich in 1942) had no love story and no additional neighbors for L.B. Jeffries to spy on, and those elements were created by Alfred Hitchcock and John Michael Hayes in the 1954 film version. Woolrich enrolled at New York's Columbia University in 1921 where he spent a re1atively undistinguished year, until he was taken ill and was laid up for some weeks. It was during this illness, a Rear-Window-like confinement involving a gangrenous foot, according to one version of the story, that Woolrich started writing, producing his first novel, the Fitzgerald-esque Cover Charge, which was published in 1926. The following year a second 'jazz-age' novel, Children of the Ritz, won a college magazine's literary prize which led to Woolrich landing a job as a Hollywood screenwriter.

Woolrich moved to Hollywood in 1928, to work under contract to First National Pictures, apparently on the script of Children of the Ritz. Whatever Woolrich did during his stint in Hollywood, he received no screen credits under his own name. Although Woolrich had published six 'jazz-age' novels-party-antics and romances of the beautiful young things on the fringes of American society-between 1926 and 1932, he was unable to establish himself as a 'serious' writer. Perhaps because the 'jazz-age' novel was dead in the water by the nineteen thirties when the depression had begun to take hold, Woolrich was unable to find a publisher for his seventh novel, I Love You, Paris, so he literally threw away the typescript--and re-invented himself as a pulp writer. -“Writing in the Darkness: The World of Cornell Woolrich” (1999) by Eddie Duggan

Woolrich's biographer Francis M. Nevins describes "Phantom Lady" (1944) as a breakthrough for both Woolrich and Siodmak. It put Woolrich on the map as a source of dark, suspenseful screen stories, and allowed Siodmak to go on to make such noir classics as The Killers (1946) and Criss Cross (1949). In his performance as Henderson’s friend Marlowe, Franchot Tone seems hell-bent on one-upping Cook’s manic skin-pounder. Thomas Gomez is more restrained, giving a characteristically solid performance as the good-hearted cop who gets the great lines “I’ll get the murderer sooner or later. It’s always easier when they’re insane.”

Phantom Lady is prime Woolrich. Between 1942 and 1950, 15 Hollywood movies were made from Woolrich’s work. In 1946, his best year for sales, Woolrich earned around $60,000. But as time went on too many of his properties were sold for too little. Woolrich bitterly recalled that Alfred Hitchock paid $600 for the movie rights to Rear Window. Woolrich’s agent H. N. Swanson sold that story and seven others for $5,000. Woolrich’s first two novels showed the influence of his hero F. Scott Fitzgerald. His second book, Children of the Ritz (1927), won a $10,000 prize from College Humour magazine. -Ben Terrall (Noir City, Winter 2015)

In West of Sunset, novelist Stewart O' Nan imagines F. Scott Fitzgerald's final years, which he spent in Hollywood. The book opens in 1937 in North Carolina, where Fitzgerald is "just eking out a living" writing short stories, O'Nan tells NPR's Scott Simon. He is deeply in debt to his agent Harold Ober, O'Nan explains, "but he sees a chance to get out of debt by going to Hollywood and he seizes it." "Having nothing to add, with a view of the whole room, Scott lost himself in stargazing. Right beside Ronald Colman, Spencer Tracy was tucking into a tripledecker club; next to him, her famous lips pursed, Katharine Hepburn blew on a spoonful of tomato soup. Mayer and Cukor were showily spinning an hourglass-shaped cage of dice to see who’d pay. It was much like Cottage, his dining club at Princeton: while the place was open to all, the best tables were tacitly reserved for the chosen. The rest of them were extras." -"West of Sunset" (2014) by Stewart O'Nan

Ann Todd and Trevord Howard in "The Passionate Friends" (1948) directed by David Lean

Wells, H. G. (1866–1946) English novelist now best known for his science-fiction romances, including The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), and The Passionate Friends: A Novel (1913). Fitzgerald reviewed God, the Invisible King (1917) for the the Nassau Literary Magazine and in 1917 called The New Machiavelli (1911) “the greatest English novel of the century” (to Edmund Wilson, 1917). Wells influenced This Side of Paradise - his novel The Research Magnificent (1915) was one of the “quest novels” that influenced Amory Blaine, and Rosalind Connage is partly based on Beatrice Normandy from Tono-Bungay (1909).

When Edmund Wilson read the typescript of This Side of Paradise in November 1919, he described it as “an exquisite burlesque of Compton Mackenzie with a pastiche of Wells thrown in at the end”. However, Fitzgerald renounced Wells’s influence: “Such a profound and gifted man as John Dos Passos should never enlist in Wells’ faithful but aenemic platoon along with Walpole, Floyd Dell and Mencken’s late victim, Ernest Poole. The only successful Wellsian is Wells. Let us slay Wells, James Joyce and Anatole France that the creation of literature may continue”. Wells’s Outline of History (1920) was the foundation of Fitzgerald’s “College of One” plan for educating Sheilah Graham. In F. Scott Fitzgerald: His Art and His Technique, James E. Miller, Jr., sees the change from This Side of Paradise to The Great Gatsby as a very conscious change in Fitzgerald’s movement away from H. G. Wells’s technique of “saturation” toward Henry James’s technique of “selection”. Fitzgerald renounced Wells’s influence in his review of John Dos Passos’s Three Soldiers (1921), and his thinking through to “selection” as an essential aspect of the writer’s craft accounts for his strong criticism of Thomas Wolfe’s work.-"H. G. Wells: Aspects of a Life" (1985) by Anthony West

The Seventh Veil (1945) - British Classic Noir - Full Movie, starring James Mason, Ann Todd, Herbert Lom...The movie begins with Francesca (Ann Todd) in the hospital—mental hospital it’s soon revealed. Recovering from her unsuccessful suicide attempt, she tells her life’s story to psychiatrist Dr. Larsen (Herbert Lom). This is one of those rare films where the psychiatrist doesn’t fall in love with his patient.

She relates going to live with her crippled, pianist guardian, Nicholas, who imperiously turns her piano talents into concert pianist proportions. And she dutifully becomes famous, as a love of music drives her as much as it drives her cousin. Francesca’s first love is an “American” band leader (British actor Hugh McDermott, sans an American accent), but when she informs Nicholas she plans to marry, he decrees otherwise, as he is her guardian until she’s twenty-one. Nicholas commissions him to paint her portrait, which eventually hangs on Nicholas’ wall, á la Gene Tierney’s portrait in Laura, Joanne Woodward’s in Sleuth, Jennifer Jones’ in Portrait of Jennie.

Source: classicfilmfreak.com

The Passionate Friends (1948) - David Lean David Lean's film adaptation of the H. G. Wells story, starring Ann Todd, Trevor Howard and Claude Rains.

Ann Todd plays Sylvia Leeds Kent in "Sylvia" from "Alfred Hitchcock presents" (19 Jan. 1958)

Sylvia is a young woman who we think is contemplating suicide. Her ex-husband, Peter, married her for money. When he forged a check, her father agreed not to prosecute if he divorced her. Now Sylvia is again in touch with Peter, and wants him back. Peter calls her father and tells him that he will stay out of her life for a price. Sylvia's father tells her about his blackmail scheme, and she tells him that she bought a gun to use on Peter if they did not get back together. She goes to her room alone and is followed by her father, who is worried about her and tries to retrieve the gun.

The original "Rear Window" ("It Had to Be Murder", written by Cornell Woolrich in 1942) had no love story and no additional neighbors for L.B. Jeffries to spy on, and those elements were created by Alfred Hitchcock and John Michael Hayes in the 1954 film version. Woolrich enrolled at New York's Columbia University in 1921 where he spent a re1atively undistinguished year, until he was taken ill and was laid up for some weeks. It was during this illness, a Rear-Window-like confinement involving a gangrenous foot, according to one version of the story, that Woolrich started writing, producing his first novel, the Fitzgerald-esque Cover Charge, which was published in 1926. The following year a second 'jazz-age' novel, Children of the Ritz, won a college magazine's literary prize which led to Woolrich landing a job as a Hollywood screenwriter.

Woolrich moved to Hollywood in 1928, to work under contract to First National Pictures, apparently on the script of Children of the Ritz. Whatever Woolrich did during his stint in Hollywood, he received no screen credits under his own name. Although Woolrich had published six 'jazz-age' novels-party-antics and romances of the beautiful young things on the fringes of American society-between 1926 and 1932, he was unable to establish himself as a 'serious' writer. Perhaps because the 'jazz-age' novel was dead in the water by the nineteen thirties when the depression had begun to take hold, Woolrich was unable to find a publisher for his seventh novel, I Love You, Paris, so he literally threw away the typescript--and re-invented himself as a pulp writer. -“Writing in the Darkness: The World of Cornell Woolrich” (1999) by Eddie Duggan

Woolrich's biographer Francis M. Nevins describes "Phantom Lady" (1944) as a breakthrough for both Woolrich and Siodmak. It put Woolrich on the map as a source of dark, suspenseful screen stories, and allowed Siodmak to go on to make such noir classics as The Killers (1946) and Criss Cross (1949). In his performance as Henderson’s friend Marlowe, Franchot Tone seems hell-bent on one-upping Cook’s manic skin-pounder. Thomas Gomez is more restrained, giving a characteristically solid performance as the good-hearted cop who gets the great lines “I’ll get the murderer sooner or later. It’s always easier when they’re insane.”

Phantom Lady is prime Woolrich. Between 1942 and 1950, 15 Hollywood movies were made from Woolrich’s work. In 1946, his best year for sales, Woolrich earned around $60,000. But as time went on too many of his properties were sold for too little. Woolrich bitterly recalled that Alfred Hitchock paid $600 for the movie rights to Rear Window. Woolrich’s agent H. N. Swanson sold that story and seven others for $5,000. Woolrich’s first two novels showed the influence of his hero F. Scott Fitzgerald. His second book, Children of the Ritz (1927), won a $10,000 prize from College Humour magazine. -Ben Terrall (Noir City, Winter 2015)

In West of Sunset, novelist Stewart O' Nan imagines F. Scott Fitzgerald's final years, which he spent in Hollywood. The book opens in 1937 in North Carolina, where Fitzgerald is "just eking out a living" writing short stories, O'Nan tells NPR's Scott Simon. He is deeply in debt to his agent Harold Ober, O'Nan explains, "but he sees a chance to get out of debt by going to Hollywood and he seizes it." "Having nothing to add, with a view of the whole room, Scott lost himself in stargazing. Right beside Ronald Colman, Spencer Tracy was tucking into a tripledecker club; next to him, her famous lips pursed, Katharine Hepburn blew on a spoonful of tomato soup. Mayer and Cukor were showily spinning an hourglass-shaped cage of dice to see who’d pay. It was much like Cottage, his dining club at Princeton: while the place was open to all, the best tables were tacitly reserved for the chosen. The rest of them were extras." -"West of Sunset" (2014) by Stewart O'Nan

Ann Todd and Trevord Howard in "The Passionate Friends" (1948) directed by David Lean

Wells, H. G. (1866–1946) English novelist now best known for his science-fiction romances, including The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), and The Passionate Friends: A Novel (1913). Fitzgerald reviewed God, the Invisible King (1917) for the the Nassau Literary Magazine and in 1917 called The New Machiavelli (1911) “the greatest English novel of the century” (to Edmund Wilson, 1917). Wells influenced This Side of Paradise - his novel The Research Magnificent (1915) was one of the “quest novels” that influenced Amory Blaine, and Rosalind Connage is partly based on Beatrice Normandy from Tono-Bungay (1909).

When Edmund Wilson read the typescript of This Side of Paradise in November 1919, he described it as “an exquisite burlesque of Compton Mackenzie with a pastiche of Wells thrown in at the end”. However, Fitzgerald renounced Wells’s influence: “Such a profound and gifted man as John Dos Passos should never enlist in Wells’ faithful but aenemic platoon along with Walpole, Floyd Dell and Mencken’s late victim, Ernest Poole. The only successful Wellsian is Wells. Let us slay Wells, James Joyce and Anatole France that the creation of literature may continue”. Wells’s Outline of History (1920) was the foundation of Fitzgerald’s “College of One” plan for educating Sheilah Graham. In F. Scott Fitzgerald: His Art and His Technique, James E. Miller, Jr., sees the change from This Side of Paradise to The Great Gatsby as a very conscious change in Fitzgerald’s movement away from H. G. Wells’s technique of “saturation” toward Henry James’s technique of “selection”. Fitzgerald renounced Wells’s influence in his review of John Dos Passos’s Three Soldiers (1921), and his thinking through to “selection” as an essential aspect of the writer’s craft accounts for his strong criticism of Thomas Wolfe’s work.-"H. G. Wells: Aspects of a Life" (1985) by Anthony West

Wednesday, January 21, 2015

Orwell's political morality, Capra's American Dream, Eastwood's American Sniper

The 100 best novels: No 70 – Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell (1949): “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” Even as a child, he had been fascinated by the futuristic imagination of HG Wells (and later, Aldous Huxley). Finally, at the end of his short life, he fulfilled his dream. Nineteen Eighty-Four, arguably the most famous English novel of the 20th century, is a zeitgeist book. Orwell’s dystopian vision was deeply rooted both in its author’s political morality, and in its time, the postwar years of western Europe. After the third world war, Britain is now Airstrip One in the American superstate of Oceania, permanently in conflict with Eurasia and Eastasia. Winston Smith, a former journalist employed by the Ministry of Truth to rewrite old newspaper articles so that the historical record always supports state policy, decides to launch his own hopeless private rebellion against the oppression of “the Party” and its all-seeing, all-powerful dictator, Big Brother. Source: www.theguardian.com

The rise of Frank Capra from sickly, abused, impoverished Sicilian immigrant to what one of his sons calls “a shaper of how we view America” is the subject of Kenneth Bowser’s Frank Capra’s American Dream. This biography, produced by Tom and Frank Capra, Jr., attempts to replace the simplistic image of Capra as a sort of undiscriminating, sentimental populist with a more complex reality. What emerges from these interviews and film clips is an illuminating portrait of a tragically conflicted personality whose work, more than that of many directors, is barely veiled autobiography. The Capra seen here joins his fictional counterparts — Mr. Deeds, Mr. Smith, and John Doe — as an Everyman whose sudden wealth and fame, those driving myths of the “American Dream” that was Capra’s eternal subject, nearly destroy him. Source: brightlightsfilm.com

Harry Cohn believed that as an outsider, Frank Capra could not afford to dabble in global politics without having his loyalty questioned. Hollywood was already seen by too much of the rest of America as a nest of perversion and subversion, and the industry’s growing population of foreign-born filmmakers, writers, and actors had to walk an especially careful line. Capra’s infatuation with Mussolini soon subsided, but his sympathies remained maddeningly difficult to track, even for those who knew him. He supported Franco during the Spanish Civil War while most of his Hollywood colleagues were raising funds for the Loyalists.

At any given moment, Capra’s passions could be inflamed by populism or by distrust of the working class, by loathing for Communists or contempt for capitalists, by economic self-protection or New Deal generosity. Throughout the 1930s, his politics had been defined more by his quick temper than by any ideological consistency. His conflicting impulses were manifest in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, a comedy about an eccentric young New England poet who inherits $20 million and learns what it’s like to have the whole world reach into his pockets. Capra’s left-wing screenwriter Robert Riskin brought an unmistakable progressivism to the film, especially in an episode in which a farmer is driven to madness by his inability to feed and clothe his family in the Depression; his plight moves Deeds to a quasi-socialistic resolve to spread the wealth. But the movie’s ideas, and its ideals, are highly mutable.

All of his contradictory perspectives were even more apparent in You Can’t Take It With You, which he started shooting in early 1938. George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s comedy about the eccentricities of a large and chaotic New York family whose elderly patriarch has for years refused to pay any income tax allowed Capra (with Riskin’s considerable help) to combine his various economic and social hobbyhorses into something approaching a unified semiphilosophy. As the opening of his movie approached, Capra was rocked by a personal tragedy. While he was at the first Los Angeles press screening of You Can’t Take It With You, he received an emergency call summoning him to the hospital, where he learned that his severely disabled three-year-old son John had died.

In 1938, Capra attended an Anti-Nazi League rally titled “Quarantine Hitler” at the Philharmonic Auditorium. Before an audience of thirty-five hundred, he stepped to the microphone and spoke in support of a trade boycott, endorsing a statement that “capitulation to Hitler means barbarism and terror.” Capra never looked back. Like Ford, he was about to become one of the movie industry’s strongest advocates for America’s involvement in what he now believed was a rapidly approaching World War.

This is one of 26 Private SNAFU ('Situation Normal, All Fouled Up') cartoons made by the US Army Signal Corps to educate and boost the morale the troops. Originally created by Theodore Geisel (Dr. Seuss) and Phil Eastman, most of the cartoons were produced by Warner Brothers Animation Studios - employing their animators, voice actors (primarily Mel Blanc) and Carl Stalling's music." Private Snafu is the title character of a series of black-and-white American instructional cartoon shorts produced between 1943 and 1945 during World War II. The character was created by director Frank Capra, chairman of the U.S. Army Air Force First Motion Picture Unit, and most were written by Theodor "Dr. Seuss" Geisel, Philip D. Eastman, and Munro Leaf. Private Snafu cartoons were a military secret—for the armed forces only. Surveys to ascertain the soldiers' film favorites showed that the Snafu cartoons usually rated highest or second highest. The Snafu shorts are notable because they were produced during the Golden Age of Warner Bros. Directors such as Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Bob Clampett, and Frank Tashlin worked on them, and their characteristic styles are in top form. The Snafu films are also partly responsible for keeping the animation studios open during the war—by producing such training films, the studios were declared an essential industry.

Mark Harris tells how Hollywood changed World War II–and vice versa–through the stories of five legendary American film directors: John Ford, William Wyler, John Huston, Frank Capra, and George Stevens. Among them they were on the scene of almost every major moment of America’s war and in every branch of service.

With more than half a million American and British soldiers and naval personnel coming from five thousand ships along fifty miles of beach in the ten days following D-Day, creating a filmed overview of those first hours and of the week that followed would have been impossible, and neither John Ford nor George Stevens intended to try. Instead, they told their men not to put themselves in unnecessary danger and to focus on what was within their own field of vision as well as on their own safety. By the end of the first day of fighting, more than four thousand Allied soldiers were dead. Fourteen of the sixteen tanks that had tried to roll onto Omaha Beach that dawn had been destroyed. Some men, laden with equipment that included eighty-pound flamethrowers, sank and drowned when their landing craft foundered in shallow waters. Others were torn apart by machine-gun fire as they walked down the ramps into the water, or died because they became entangled in underwater obstructions placed just off the shore; others were killed by snipers or mortars as they took their first steps out of the surf and onto the beach.

In the days that followed, Ford’s men moved inland with the troops, and miles away, so did Stevens and the British and American forces to which his SPECOU unit was attached. Ford and Stevens were not close friends —they were both introspective and hard to read, and in Hollywood they largely avoided the company of other filmmakers— but they did admire and respect each other. Ford thought Stevens was an “artist” —a word he rarely used about fellow directors— Eventually, the two men seem to have connected, if only briefly. -"Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War" (2014) by Mark Harris

U.S. Navy SEAL Chris Kyle (played by Oscar nominee Bradley Cooper) is sent to Iraq with only one mission: to protect his brothers-in-arms. His pinpoint accuracy saves countless lives on the battlefield and, as stories of his courageous exploits spread, he earns the nickname “Legend.” However, his reputation is also growing behind enemy lines, putting a price on his head and making him a prime target of insurgents. He is also facing a different kind of battle on the home front: striving to be a good husband and father from halfway around the world. Despite the danger, as well as the toll on his family at home, Chris serves through four harrowing tours of duty in Iraq, personifying the spirit of the SEAL creed to “leave no one behind.”

But upon returning to his wife, Taya Renae Kyle (Sienna Miller), and kids, Chris finds that it is the war he can’t leave behind. Oscar-winning filmmaker Clint Eastwood (“Million Dollar Baby,” “Unforgiven”) is directing “American Sniper” from a screenplay written by Jason Hall, based on the book by Chris Kyle, with Scott McEwan and Jim DeFelice.

Clint Eastwood’s new film is political in the highest sense of the word. He dramatizes the use and abuse of state power in the light of great philosophical ideas. “American Sniper” is a movie of violent action —but its action is surrounded by a terrible stillness. Its story of war contains valor and horror— the destructive and self-destructive conflicts that are intrinsic to a person endowed with a warrior’s noble nature. As such, it’s a cinematic tragedy in the deepest and most classical sense of the term... a truncated and telescoped cinematic Bildungsroman, telling the story of Chris’s boyhood as a sort of founding myth: how an American boy grows up to become a singularly effective soldier.

Chris is a sort of Mozart of the rifle, but it takes a particular and peculiar confluence of circumstances for him to marshal his talent for something more than sport. From the earliest age, Chris is cast in the role of protector—he defends his younger brother, Jeff, from a bully in the schoolyard—and Chris’s father sets up the scenario in a dinner-table anecdote that plays out like country Plato, saying that there are three kinds of people, wolves (predators), sheep (victims), and sheepdogs (protecting sheep against wolves).

There’s a moment, early in the film, in which Eastwood cues, in a glance, the impending tragedy: a very brief shot of Chris, seen through a doorway, heading to rodeo grounds, which borrows from the final shot of John Ford’s “The Searchers.” It’s just a touch, but it’s a brilliant one—Eastwood marks Chris, from the start, with his coming isolation. Even in the young man’s easy days of sporting adventure, his character bears the seed of the awesome price that he’ll pay for his distinction, but it’s a distinction that arises from the enduring spirit of the Western, translated into modernity—for better and worse.

For Chris, America isn’t just a homeland and a sense of self; it’s an idea, and Eastwood dramatizes the mounting nightmare of a man of unique talent who is increasingly possessed by that idea. “American Sniper” is the story of a genius in crisis; it’s a movie like Eastwood’s “Bird,” in which Charlie Parker’s singular talent comes with a self-destructive streak. Chris undergoes a singularly demanding training to become a SEAL—he dares to contradict his marksmanship instructor’s order and proves that he sees more, and better, than his instructor does. For Eastwood, the military makes a man—which war then destroys.

Eastwood sets up Chris’s fighting with a mighty, intensely focussed abstraction. The lies behind the rush to war are never explored explicitly, nor is the war in Afghanistan or any debate regarding America’s general strategies against Al Qaeda. There’s no reference to the torture of Iraqis at Abu Ghraib, to debates over the Iraq War, or to any explicit policy discussions at all. Yet the movie doesn’t convey a sense of a whitewash. Chris senses that he’s defending the faith by violating its fundamental tenets, and that he’s being celebrated for the worst part of his service—and, even more, that the celebration of warriors reveals the ignorance of the unbearable truth of battle. Even as he becomes one of American society’s heroes, Chris becomes, in his own mind, a pariah, unfit for society. Eastwood includes in the cast of “American Sniper” soldiers who have been grievously wounded in combat, soldiers who have lost limbs, whose surviving limbs have been mutilated.

It’s casting akin to that of Harold Russell, a Second World War veteran who lost his hands in combat and was fitted with prosthetic hands, in William Wyler’s 1946 masterwork “The Best Years of Our Lives.” There, Russell—who had never acted in a movie—is one of the three stars, alongside Dana Andrews and Fredric March. In the course of that drama, it’s not Russell’s character but the former fighter pilot played by Andrews who is most conspicuously suffering from the emotional traumas of combat.

“American Sniper” is an angrily cautionary film, and its anger reflects back to its very title. What’s distinctively American about Eastwood’s sniper? He’s an accidental warrior, the product of experience—of family and intimate principle, not of a military academy or a hereditary warrior class. The film’s one strange omission involves gender; there are no women soldiers featured in it, but Eastwood strongly genders Chris’s idea of the warrior, as in a passing moment when he tells his young son to “look after our women”—Chris’s wife and their infant daughter.

Whatever American distinctiveness the title may suggest, there’s one thing from which Americans aren’t excepted: war is as devastating for them as for anyone, which makes the notion of political and moral exceptionalism all the more potentially self-destructive. “American Sniper” isn’t just a tragedy; it’s an American tragedy, a vision of American destiny as tragic. Far from patriotic pomp, it’s a vision that sees past the still eye of the American self-image to the whirlwind. Source: www.newyorker.com

The rise of Frank Capra from sickly, abused, impoverished Sicilian immigrant to what one of his sons calls “a shaper of how we view America” is the subject of Kenneth Bowser’s Frank Capra’s American Dream. This biography, produced by Tom and Frank Capra, Jr., attempts to replace the simplistic image of Capra as a sort of undiscriminating, sentimental populist with a more complex reality. What emerges from these interviews and film clips is an illuminating portrait of a tragically conflicted personality whose work, more than that of many directors, is barely veiled autobiography. The Capra seen here joins his fictional counterparts — Mr. Deeds, Mr. Smith, and John Doe — as an Everyman whose sudden wealth and fame, those driving myths of the “American Dream” that was Capra’s eternal subject, nearly destroy him. Source: brightlightsfilm.com

Harry Cohn believed that as an outsider, Frank Capra could not afford to dabble in global politics without having his loyalty questioned. Hollywood was already seen by too much of the rest of America as a nest of perversion and subversion, and the industry’s growing population of foreign-born filmmakers, writers, and actors had to walk an especially careful line. Capra’s infatuation with Mussolini soon subsided, but his sympathies remained maddeningly difficult to track, even for those who knew him. He supported Franco during the Spanish Civil War while most of his Hollywood colleagues were raising funds for the Loyalists.

At any given moment, Capra’s passions could be inflamed by populism or by distrust of the working class, by loathing for Communists or contempt for capitalists, by economic self-protection or New Deal generosity. Throughout the 1930s, his politics had been defined more by his quick temper than by any ideological consistency. His conflicting impulses were manifest in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, a comedy about an eccentric young New England poet who inherits $20 million and learns what it’s like to have the whole world reach into his pockets. Capra’s left-wing screenwriter Robert Riskin brought an unmistakable progressivism to the film, especially in an episode in which a farmer is driven to madness by his inability to feed and clothe his family in the Depression; his plight moves Deeds to a quasi-socialistic resolve to spread the wealth. But the movie’s ideas, and its ideals, are highly mutable.

All of his contradictory perspectives were even more apparent in You Can’t Take It With You, which he started shooting in early 1938. George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s comedy about the eccentricities of a large and chaotic New York family whose elderly patriarch has for years refused to pay any income tax allowed Capra (with Riskin’s considerable help) to combine his various economic and social hobbyhorses into something approaching a unified semiphilosophy. As the opening of his movie approached, Capra was rocked by a personal tragedy. While he was at the first Los Angeles press screening of You Can’t Take It With You, he received an emergency call summoning him to the hospital, where he learned that his severely disabled three-year-old son John had died.

In 1938, Capra attended an Anti-Nazi League rally titled “Quarantine Hitler” at the Philharmonic Auditorium. Before an audience of thirty-five hundred, he stepped to the microphone and spoke in support of a trade boycott, endorsing a statement that “capitulation to Hitler means barbarism and terror.” Capra never looked back. Like Ford, he was about to become one of the movie industry’s strongest advocates for America’s involvement in what he now believed was a rapidly approaching World War.

This is one of 26 Private SNAFU ('Situation Normal, All Fouled Up') cartoons made by the US Army Signal Corps to educate and boost the morale the troops. Originally created by Theodore Geisel (Dr. Seuss) and Phil Eastman, most of the cartoons were produced by Warner Brothers Animation Studios - employing their animators, voice actors (primarily Mel Blanc) and Carl Stalling's music." Private Snafu is the title character of a series of black-and-white American instructional cartoon shorts produced between 1943 and 1945 during World War II. The character was created by director Frank Capra, chairman of the U.S. Army Air Force First Motion Picture Unit, and most were written by Theodor "Dr. Seuss" Geisel, Philip D. Eastman, and Munro Leaf. Private Snafu cartoons were a military secret—for the armed forces only. Surveys to ascertain the soldiers' film favorites showed that the Snafu cartoons usually rated highest or second highest. The Snafu shorts are notable because they were produced during the Golden Age of Warner Bros. Directors such as Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng, Bob Clampett, and Frank Tashlin worked on them, and their characteristic styles are in top form. The Snafu films are also partly responsible for keeping the animation studios open during the war—by producing such training films, the studios were declared an essential industry.

Mark Harris tells how Hollywood changed World War II–and vice versa–through the stories of five legendary American film directors: John Ford, William Wyler, John Huston, Frank Capra, and George Stevens. Among them they were on the scene of almost every major moment of America’s war and in every branch of service.

With more than half a million American and British soldiers and naval personnel coming from five thousand ships along fifty miles of beach in the ten days following D-Day, creating a filmed overview of those first hours and of the week that followed would have been impossible, and neither John Ford nor George Stevens intended to try. Instead, they told their men not to put themselves in unnecessary danger and to focus on what was within their own field of vision as well as on their own safety. By the end of the first day of fighting, more than four thousand Allied soldiers were dead. Fourteen of the sixteen tanks that had tried to roll onto Omaha Beach that dawn had been destroyed. Some men, laden with equipment that included eighty-pound flamethrowers, sank and drowned when their landing craft foundered in shallow waters. Others were torn apart by machine-gun fire as they walked down the ramps into the water, or died because they became entangled in underwater obstructions placed just off the shore; others were killed by snipers or mortars as they took their first steps out of the surf and onto the beach.

In the days that followed, Ford’s men moved inland with the troops, and miles away, so did Stevens and the British and American forces to which his SPECOU unit was attached. Ford and Stevens were not close friends —they were both introspective and hard to read, and in Hollywood they largely avoided the company of other filmmakers— but they did admire and respect each other. Ford thought Stevens was an “artist” —a word he rarely used about fellow directors— Eventually, the two men seem to have connected, if only briefly. -"Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War" (2014) by Mark Harris

U.S. Navy SEAL Chris Kyle (played by Oscar nominee Bradley Cooper) is sent to Iraq with only one mission: to protect his brothers-in-arms. His pinpoint accuracy saves countless lives on the battlefield and, as stories of his courageous exploits spread, he earns the nickname “Legend.” However, his reputation is also growing behind enemy lines, putting a price on his head and making him a prime target of insurgents. He is also facing a different kind of battle on the home front: striving to be a good husband and father from halfway around the world. Despite the danger, as well as the toll on his family at home, Chris serves through four harrowing tours of duty in Iraq, personifying the spirit of the SEAL creed to “leave no one behind.”

But upon returning to his wife, Taya Renae Kyle (Sienna Miller), and kids, Chris finds that it is the war he can’t leave behind. Oscar-winning filmmaker Clint Eastwood (“Million Dollar Baby,” “Unforgiven”) is directing “American Sniper” from a screenplay written by Jason Hall, based on the book by Chris Kyle, with Scott McEwan and Jim DeFelice.

Clint Eastwood’s new film is political in the highest sense of the word. He dramatizes the use and abuse of state power in the light of great philosophical ideas. “American Sniper” is a movie of violent action —but its action is surrounded by a terrible stillness. Its story of war contains valor and horror— the destructive and self-destructive conflicts that are intrinsic to a person endowed with a warrior’s noble nature. As such, it’s a cinematic tragedy in the deepest and most classical sense of the term... a truncated and telescoped cinematic Bildungsroman, telling the story of Chris’s boyhood as a sort of founding myth: how an American boy grows up to become a singularly effective soldier.

Chris is a sort of Mozart of the rifle, but it takes a particular and peculiar confluence of circumstances for him to marshal his talent for something more than sport. From the earliest age, Chris is cast in the role of protector—he defends his younger brother, Jeff, from a bully in the schoolyard—and Chris’s father sets up the scenario in a dinner-table anecdote that plays out like country Plato, saying that there are three kinds of people, wolves (predators), sheep (victims), and sheepdogs (protecting sheep against wolves).

There’s a moment, early in the film, in which Eastwood cues, in a glance, the impending tragedy: a very brief shot of Chris, seen through a doorway, heading to rodeo grounds, which borrows from the final shot of John Ford’s “The Searchers.” It’s just a touch, but it’s a brilliant one—Eastwood marks Chris, from the start, with his coming isolation. Even in the young man’s easy days of sporting adventure, his character bears the seed of the awesome price that he’ll pay for his distinction, but it’s a distinction that arises from the enduring spirit of the Western, translated into modernity—for better and worse.

For Chris, America isn’t just a homeland and a sense of self; it’s an idea, and Eastwood dramatizes the mounting nightmare of a man of unique talent who is increasingly possessed by that idea. “American Sniper” is the story of a genius in crisis; it’s a movie like Eastwood’s “Bird,” in which Charlie Parker’s singular talent comes with a self-destructive streak. Chris undergoes a singularly demanding training to become a SEAL—he dares to contradict his marksmanship instructor’s order and proves that he sees more, and better, than his instructor does. For Eastwood, the military makes a man—which war then destroys.

Eastwood sets up Chris’s fighting with a mighty, intensely focussed abstraction. The lies behind the rush to war are never explored explicitly, nor is the war in Afghanistan or any debate regarding America’s general strategies against Al Qaeda. There’s no reference to the torture of Iraqis at Abu Ghraib, to debates over the Iraq War, or to any explicit policy discussions at all. Yet the movie doesn’t convey a sense of a whitewash. Chris senses that he’s defending the faith by violating its fundamental tenets, and that he’s being celebrated for the worst part of his service—and, even more, that the celebration of warriors reveals the ignorance of the unbearable truth of battle. Even as he becomes one of American society’s heroes, Chris becomes, in his own mind, a pariah, unfit for society. Eastwood includes in the cast of “American Sniper” soldiers who have been grievously wounded in combat, soldiers who have lost limbs, whose surviving limbs have been mutilated.

It’s casting akin to that of Harold Russell, a Second World War veteran who lost his hands in combat and was fitted with prosthetic hands, in William Wyler’s 1946 masterwork “The Best Years of Our Lives.” There, Russell—who had never acted in a movie—is one of the three stars, alongside Dana Andrews and Fredric March. In the course of that drama, it’s not Russell’s character but the former fighter pilot played by Andrews who is most conspicuously suffering from the emotional traumas of combat.

“American Sniper” is an angrily cautionary film, and its anger reflects back to its very title. What’s distinctively American about Eastwood’s sniper? He’s an accidental warrior, the product of experience—of family and intimate principle, not of a military academy or a hereditary warrior class. The film’s one strange omission involves gender; there are no women soldiers featured in it, but Eastwood strongly genders Chris’s idea of the warrior, as in a passing moment when he tells his young son to “look after our women”—Chris’s wife and their infant daughter.

Whatever American distinctiveness the title may suggest, there’s one thing from which Americans aren’t excepted: war is as devastating for them as for anyone, which makes the notion of political and moral exceptionalism all the more potentially self-destructive. “American Sniper” isn’t just a tragedy; it’s an American tragedy, a vision of American destiny as tragic. Far from patriotic pomp, it’s a vision that sees past the still eye of the American self-image to the whirlwind. Source: www.newyorker.com

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)