“Why do you hate me?” I asked Jay again in our Belleville apartment. I was going to keep asking until I got an answer out of him. He didn’t deny it. If anything, he looked surprised that I didn’t already know the answer. 20 years later I was shocked to learn from a magazine interview with Jay Farrar that there was an “incident” that he saw as the last straw. Something that I’d completely forgotten about. Apparently still an “incident” he’d never forgiven me for. We had just finished a show in St. Louis, and this was back when I was still drinking so it was before our first record deal. I never made another record with alcohol in my bloodstream after No Depression. Jay’s girlfriend, Monica, had gotten tipsy during the show, and she fell asleep in the back of our van, waiting for us to load out. Jay was our designated driver for the night, so he was mostly sober. After we loaded out, I stumbled into the van and sat next to Monica. She woke up, and we started talking with incoherent babbling. We were leaning in to each other, and I was earnestly slurring, “I love you, Monica. I’ve always loved you.” Monica was sweetly slurring right back, not without pity, “Aw, I love you, too, Jeff.” Innocent stuff. Obnoxious, maybe, but not anything with sinister motives. I was just a drunk having a bad case of loving everyone. Jay heard it all and watched our inebriated snuggling unfold from the van’s rearview mirror. He was upset, which he had every right to be. If some drunk started weepingly confessing his love for my girlfriend, I’d be pissed, too. Jay confronted me about it when we got back home. He thought I was hitting on her, or trying to seduce her. Even in my drunken stupor, that hadn’t been my intention. I was trying to tell a friend how much she meant to me, and because of the alcohol, I was doing it stupidly. There wasn’t any attempts at kissing, nothing even remotely sexual. It was just two drunks telling each other, “I love you.” As drunks do. That was still too much for Jay to bear. When we got back to Belleville, I apologized, he quit the band, and I’m pretty sure I cried. It was a big deal. I knew I’d fucked up, and it inspired me to quit drinking, which I somehow managed to do. Years later, when he was interviewed, he talked about that night in the van like it was the ultimate betrayal, the moment that killed Uncle Tupelo. His telling added details that were villainous, like that I’d been stroking Monica’s hair (that doesn’t sound like me).

Even without alcohol I still have an impulse from time to time to mope and feel sorry for myself and want to be taken care of. The cure? My badass wife. She simply won’t have that shit. Not even a tiny bit. You know, “Sex, drugs, and rock and roll”? I always kind of looked down on championing anything but the rock and roll part. Anyone can do drugs or have sex or do sex-drugs or have drug-sex. To me, rock and roll required more awareness and commitment. My first sexual encounter was at the age of fourteen. The unfortunate truth of how I lost my virginity is the specific type of sexual initiation which is still romanticized as a “You hit the jackpot” kind of fantasy. The older woman taking a male virgin and teaching him carnality is a scenario still accepted as not just okay but ideal. Any naysaying to the contrary is casually shamed into silence by the pervasive masculinity of our collective mind-set. Well, the truth is, it was as wrong and damaging as would be easily accepted were the gender roles reversed. At fourteen, I wasn’t anywhere near being emotionally prepared to dive into that. I enjoyed hanging out with Leslie. She was twenty-five and loved great music. She was funny, and I just thought of her as my friend. Toward the end of the summer before my sophomore year in high school, she informed me she was planning to leave Belleville and move back to her hometown. So we listened to music, and then she said we should leave because her roommate was coming soon. She grabbed a bottle of champagne from her fridge, a blanket, and took me to a nearby park. It was dark and empty, we laid on the blanket and passed the champagne, and then she climbed on top of me. I didn’t fight it, but it felt very wrong. I don’t know what I was expecting to happen, but I swear a part of me was still waiting for her to give me an album or some token to remember her by. So that’s how it happened. Technically, I was consenting, but only so far as a fourteen-year-old can consent. I told a few friends, trying to find a way to express the pain and confusion of the whole ordeal. Instead, because I was a guy, among my guy friends, my statutory victimhood was celebrated. Even to the point of jealousy at my good fortune. My mom knew something was wrong, but I was sickened by the thought of sharing any of it with her. I know my dad genuinely loved my mom. And she loved him, too, but maybe not as much. When I was a kid, I thought that she wasn’t getting what she needed emotionally from him. But in hindsight, it was probably the other way around. It was my dad who had no chance. She wasn’t going to trust a man with her happiness.

To exalt an artist’s suffering as being somehow unique or noble makes me cringe. When someone’s heart aches because a girl said she still loved him but really she was sleeping with somebody else and that made him sad, they’re plugged into something universal—if we all learn anything from being alive on this planet, it’s that people will lie to you for different motives. I love old records. I definitely love sad songs the most. It was not about being able to write the perfect lyrics or a melody that will crawl up inside a listener’s head and never leave. It was realizing that I’m okay being vulnerable. My comfort level with being vulnerable is probably my superpower. I wasn’t the cool kid. I wasn’t the strongest. I wasn’t the smartest person. I wasn’t the one you turned to if you had a question. I wasn’t ruggedly handsome or boyishly charming. I wasn’t the captain of the football team, or the kid everybody in school voted was the most likely to succeed. I was the guy who could burst into tears in front of his peers and not care what they thought. I had a bone-crushing earnestness, a weaponized sincerity, and I was learning how to put all of those feelings into songs. I was impervious to my peers’ shame. They couldn’t make me recoil with their snickering or judgmental sneers. I’d sung these same songs to my mother, in the quiet of our kitchen, and if I could open up to her and not be destroyed by a disapproving arch of an eyebrow, what could a crowd of strangers possibly do?

The way I feel about my wife Susie, the way she’s loved me and changed me, it can’t be in my songs. It’s too big for songs. Maybe, occasionally, I can get a part of it to fit. Sometimes it gets deep in the track where I can feel it but it’s never put into words. If you’ve ever been in a relationship that you took for granted, even when it was the one thing holding you together, and you somehow didn’t lose it despite acting like an idiot, then you know how difficult it is to convey that amount of gratitude, much less set it to music. I wouldn’t know where to begin. 'Let’s go so we can get back'—interview with Jeff Tweedy. Source: www.rollingstone.com

Wilco was out in full force at the Val Air—one of those venerable Midwestern ballrooms where big bands once played, on the same circuit as Buddy Holly’s fatal tour. Behind the buoyant melodic simplicity of Tweedy’s acoustic guitar on the set-opening “Handshake Drugs”, guitarist Nels Cline raised a squall reminiscent of Neil Young with Crazy Horse, while drummer Glenn Kotche (who served as opening act and encore returnee on the solo tour) provided punctuation throughout the set that went well beyond typical rock propulsion. “Nobody suffers like that dude!” Tweedy said in the voice of a fan, both summarizing and satirizing what has seemed to be a large part of his appeal in recent years as Wilco’s brooding, mercurial frontman. Tweedy seemed almost borderline giddy that night. At least that was the impression reinforced during Wilco’s performance of the beatlesque “Hummingbird” to a decidedly older Des Moines crowd than the one at the university, where he exercised the dorkiest of rock star moves by running in place for extended mid-song calisthenics. Source: www.nodepression.com

“They don’t make music the way they used to,” the boomers and Gen Xers will mutter. And they’ll be right. Music today, at least most of it, is fundamentally different from what it was in the days of yore. For decades, musicians and engineers have employed dynamic range compression to make recordings sound fuller. Compression boosts the quieter parts and tamps down louder ones to create a narrower range. Historically, compression was usually applied during the mastering stage, the final steps through which a finished recording becomes a commercial release. The compression of dynamic range—the gap between the loud and quiet moments—of popular music has been used in recording studios for decades. The more aggressive use of compression in recent years is illustrated by these two song samples. In “This Is America,” the peak levels are clipped and the average loudness is less varied than in “What’s Going On.” The distance between the peaks and the average, a measure of how much the song’s range has been squeezed, is six decibels greater in Marvin Gaye’s song than it is in Childish Gambino’s track. In the predigital era, compression required a mastering engineer whose job is to create the physical master for the manufacturing process, to employ restraint and finesse. With digital audio, a few mouse clicks can compress the dynamic range with brute force. The result is music that sounds more aurally aggressive — like the television commercials. During the 1990s, as digital technology infiltrated the recording process, some mastering engineers wielded compression like a cudgel, competing to produce the loudest recordings. This recording industry “loudness war” was driven by linked aesthetic and economic imperatives. Maximum loudness, it was thought, was a prerequisite for commercial success. Over time, with listeners increasingly consuming music through earbuds and cheap computer speakers, engineers and producers found themselves working in a denuded sonic landscape, many of them longing for the rich and diverse audio ecosystems of old. Source: www.nytimes.com

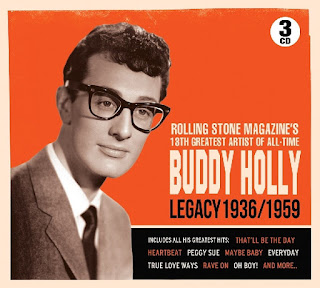

Mike Berry's version of the song that Buddy Holly never recorded himself. In New York Buddy Holly also formed the 'Maria Music' publishing company with which "Stay Close To Me" was filed. Buddy Holly produced Lou Giordano's version of the song which was issued on Brunswick Records (55115) on January 27, 1959.

"I dreamed the girl I’d marry and the family we’d raise/In the mountains of New York City precious would be those days/But what my heart could not foresee thought these dreams would come through/My time remaining would be brief I give these dreams to you/You and me my brother in these guitars we trust/Our dreams might not mean much to the world but/They mean the world to us." —"Visionary Heart" (2016), a song written by Dion Dimucci dedicated to Buddy Holly

Some fans were often quick to sense that a veritable ‘Superman’ lurked beneath his ‘Clark Kentish’ exterior. Although Buddy Holly had composed the brilliant Reminiscing, he gave saxophonist King Curtis songwriter credits as part of his fees for flying to Clovis' recording studios. Detailing the woes of a jilted lover, Buddy’s characteristic hiccups and Curtis’ bawdy saxophone express a sense of longing for love without being maudlin. Murray Deutch, a Peer Southern executive who had received “some good songs” from Norman Petty in the past, never established a kinship with the Clovis producer: “Warmth wasn’t something you got with Norman Petty. He was the kind of guy who’d give you ice in the wintertime.” Going by legend, J.P. Richardson (The Big Bopper), who was battling flu like symptoms, approached Waylon Jennings about possibly taking his place on the plane. His hope was to get to the next venue early enough to get a shot from a doctor to battle his cold. Tommy Allsup has always maintained that he was approached by Ritchie Valens throughout the night about taking his place on board the airplane. However, Surf Ballroom's manager Carroll Anderson had a different recall about how Valens and Richardson wound up on that flight, and it differs dramatically from the memories of Waylon Jennings and Tommy Allsup. Carroll Anderson: “Buddy Holly got ahold of the Big Bopper, and the Big Bopper said, ‘Well, I’ll go with you if you split it.’ And then Holly said, ‘Let’s take Ritchie Valens along and it’ll only cost us thirty six dollars apiece.’”

Carroll Anderson’s memories of what went on that night in arranging the charter and the subsequent passengers that wound up on board a doomed Bonanza comes pretty damn close to substantiating Dion DiMucci’s story on what went on that evening when it came to who was to fly and who wasn’t. Dion DiMucci (“Dion: The Wanderer Talks Truth”): “Buddy gathered up the headliners and told us he couldn’t take another night on the bus; he was going to try to charter a plane to take us to the next stop on the tour, Moorhead, Minnesota. He found a single―engine craft that could sit three in addition to the pilot. The problem was that there were four headliners―Buddy, Ritchie, the Big Bopper, and me. Someone would have to ride the bus. In a closed dressing room, we flipped a coin to see who was going to fly. The Big Bopper and I won the toss. Then Buddy told us what the flight would cost: $36. I couldn’t bring myself to spend a month’s rent on an hour’s flight to Minnesota. I said to Ritchie, ‘You go.’ Only the four of us knew who was getting on the plane when we left the dressing room that night. Of the four who were in that room, I’m the only one who survived beyond February 3, 1959.” Jennings’ comment about Holly, Richardson and Valens being “bugs for flying” denotes that there was much interest expressed prior to that tragic February 3rd plane ride by the three singers in flying. Much has been made over how Allsup stuck to the same story with little variation since the 1970s, yet little has been made over the consistency of Carroll Anderson’s memories of that night, even though his recollections changed little over the years, too, and seem to fly in direct contrast to Mr. Allsup’s own story. ―"In Flanders Field: Death and Rebirth of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. Richardson" (2017) by Ryan Vandergriff

Some fans were often quick to sense that a veritable ‘Superman’ lurked beneath his ‘Clark Kentish’ exterior. Although Buddy Holly had composed the brilliant Reminiscing, he gave saxophonist King Curtis songwriter credits as part of his fees for flying to Clovis' recording studios. Detailing the woes of a jilted lover, Buddy’s characteristic hiccups and Curtis’ bawdy saxophone express a sense of longing for love without being maudlin. Murray Deutch, a Peer Southern executive who had received “some good songs” from Norman Petty in the past, never established a kinship with the Clovis producer: “Warmth wasn’t something you got with Norman Petty. He was the kind of guy who’d give you ice in the wintertime.” Going by legend, J.P. Richardson (The Big Bopper), who was battling flu like symptoms, approached Waylon Jennings about possibly taking his place on the plane. His hope was to get to the next venue early enough to get a shot from a doctor to battle his cold. Tommy Allsup has always maintained that he was approached by Ritchie Valens throughout the night about taking his place on board the airplane. However, Surf Ballroom's manager Carroll Anderson had a different recall about how Valens and Richardson wound up on that flight, and it differs dramatically from the memories of Waylon Jennings and Tommy Allsup. Carroll Anderson: “Buddy Holly got ahold of the Big Bopper, and the Big Bopper said, ‘Well, I’ll go with you if you split it.’ And then Holly said, ‘Let’s take Ritchie Valens along and it’ll only cost us thirty six dollars apiece.’”

Carroll Anderson’s memories of what went on that night in arranging the charter and the subsequent passengers that wound up on board a doomed Bonanza comes pretty damn close to substantiating Dion DiMucci’s story on what went on that evening when it came to who was to fly and who wasn’t. Dion DiMucci (“Dion: The Wanderer Talks Truth”): “Buddy gathered up the headliners and told us he couldn’t take another night on the bus; he was going to try to charter a plane to take us to the next stop on the tour, Moorhead, Minnesota. He found a single―engine craft that could sit three in addition to the pilot. The problem was that there were four headliners―Buddy, Ritchie, the Big Bopper, and me. Someone would have to ride the bus. In a closed dressing room, we flipped a coin to see who was going to fly. The Big Bopper and I won the toss. Then Buddy told us what the flight would cost: $36. I couldn’t bring myself to spend a month’s rent on an hour’s flight to Minnesota. I said to Ritchie, ‘You go.’ Only the four of us knew who was getting on the plane when we left the dressing room that night. Of the four who were in that room, I’m the only one who survived beyond February 3, 1959.” Jennings’ comment about Holly, Richardson and Valens being “bugs for flying” denotes that there was much interest expressed prior to that tragic February 3rd plane ride by the three singers in flying. Much has been made over how Allsup stuck to the same story with little variation since the 1970s, yet little has been made over the consistency of Carroll Anderson’s memories of that night, even though his recollections changed little over the years, too, and seem to fly in direct contrast to Mr. Allsup’s own story. ―"In Flanders Field: Death and Rebirth of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. Richardson" (2017) by Ryan Vandergriff