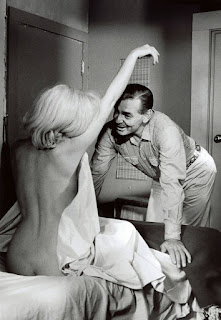

Soon there were Marilyn's visits to Joe DiMaggio’s home on Beach Street in San Francisco, the house he had bought for $14,000 in the early days of his success and where his sister Marie played hostess. Sometimes the couple would go fishing, Marilyn bundled up in leather jacket, jeans, and scarf. They were rarely recognized, and the times when they were spotted DiMaggio angrily told reporters to ‘beat it.’ On his home turf, DiMaggio offered a tranquility rarely experienced by Marilyn. On the matter of his brief marriage to Marilyn, their divorce and moving reunion, Joe DiMaggio’s intact silence is well known and can only be respected. “I didn’t want to give up my career,” Marilyn had said to columnist Earl Wilson, “and that’s what Joe wanted me to do most of all. He wanted me to be the beautiful ex-actress, just like he was the great former ballplayer. We were to ride into some sunset together. But I wasn’t ready for that kind of journey yet. I wasn’t even thirty, for heaven’s sake!” On his deathbed, Joe DiMaggio said in 1999: “I don’t feel bad about dying. At least, I’ll be with Marilyn again.” It was not the first time DiMaggio had said that, according to Morris Engelberg. “We were sitting together in the patio one night, talking about his illness, and he said he wished to be with Marilyn again.”

Dinner With DiMaggio: Memories of an American Hero promises a rare glimpse into the private life of a frequently misunderstood man, and although occasionally prone to sensationalism, for the most part it delivers. Joe met his first wife, showgirl Dorothy Arnold, on a film set. Their son, Joe DiMaggio Jr., was born in 1941, but the couple were soon embroiled in a bitter divorce. “Dorothy was always trying to get between my little guy and me,” Joe told his friend Dr. Rock Positano. Although he was a lifelong movie fan, Joe’s brushes with Hollywood left him unimpressed. In the late 1940s, he was dining at the Stork Club with some of the biggest names in the movie industry, including Marlene Dietrich and the Bogarts. “I knew better than to pry,” Positano says, claiming that Joe gradually opened up. “He also spoke with [lawyer] Morris Engelberg about Marilyn,” he adds, “but I never knew what he told each of us, and Morris and I never compared notes.”

Joe thought Marilyn was both beautiful and “highly intelligent,” as Positano revealed in a recent interview for People magazine. “He had a tremendous amount of respect for Marilyn because she was a really great actress.” Nonetheless, her star was rising when she married Joe, and babies seem not to have been an immediate priority. His jealousy, and her ambition, were more likely causes of the split. When crowds gathered to watch her standing over a subway grate during filming of The Seven Year Itch, columnist Walter Winchell dragged a reluctant Joe along. The couple separated shortly afterward. “Doc, Marilyn told me that no man ever satisfied her like I did,” Joe said. Although respectful in public, Joe apparently took a dim view of her third husband, Arthur Miller. Sinatra told Joe that Marilyn kept a photo of him hidden in a closet, which “drove Miller crazy and right to the divorce court.” In the final years of her life, Marilyn grew close to Joe again. Talk of reconciliation was rife, but she insisted they were just good friends. Joe had probably been hurt by Marilyn’s relationship with Frank Sinatra, but by 1962, when her alleged involvement with John F. Kennedy occurred, the president had distanced himself from Sinatra. Positano repeats the tale of Joe snubbing Bobby Kennedy at Yankee Stadium in 1965. Marilyn had a long history of depression, and was addicted to sleeping pills. Joe told Positano that she would sometimes neglect her appearance. “Though Joe saw Marilyn’s behaviour become erratic, he was unsophisticated about mental illness,” Positano reflects. During his final trip to New York in 1999, a frail Joe was in a nostalgic mood. “I miss Marilyn more than ever,” he confided. One of his proudest achievements was the opening of the Joe DiMaggio Children’s Hospital in Florida.

One of Lee Strasberg’s standard suggestions—practically a requirement—was that students enhance their reservoir of primal memories and emotions (what he called “sense memory”) by entering psychoanalysis. He and Paula were undergoing analysis, and both felt, among its other advantages, that it had strengthened their marriage. Turning to Milton Greene for advice on the subject, Marilyn was soon given a referral. Greene himself had been in therapy for several years with Dr. Margaret Herz Hohenberg, who, like Lee Strasberg, had come to the United States from Hungary. A follower of the Viennese school of psychoanalysis founded by Sigmund Freud, Hohenberg, at fifty-seven, was a tall, heavy woman with white hair that was often braided and wrapped around her head. On Milton Greene’s recommendation, Marilyn met with the analyst. By March 1955, she was seeing Margaret Hohenberg five times a week.

Monroe’s presence on the block did not go unnoticed; Hohenerg’s neighbors would frequently stop her on the street and inquire, “How is Miss Monroe doing today?” During their sessions, for which Marilyn invariably arrived late, they dealt with the traumas of Monroe’s chaotic childhood, her lack of self-esteem, her lust for approval, her dread of rejection, her obsessive search for a father figure. To facilitate the analytic process, the actress recorded her thoughts and dreams in a series of binders that, in 2010, were posthumously published as a single volume called Fragments, which seemed an appropriate title considering Hohenberg’s pronouncement, made soon after she met Marilyn, that the actress possessed “a fragmented mind.” Typical of Marilyn’s nightmarish notations in Fragments is one that reads: “For Dr. H—Tell her about that dream of the horrible, repulsive man—who is trying to lean too close to me in the elevator—and my panic and then my thought despising him—does that mean I’m attached to him? He even looks like he has a venereal disease.” After six months of treatment, Hohenberg diagnosed Monroe as suffering from borderline personality disorder, a psychological condition characterized by intense turmoil and instability in relationships and behavior.

Marilyn demonstrated two of the conditions commonly associated with Borderline Personality Disorder: dissociation and depersonalization. Under stress, her mind and body would literally shut down, which helped explain (at least to Hohenberg) why Marilyn was always late for appointments and had difficulty remembering her lines when appearing in films. Strangely enough, Hohenberg also determined that Marilyn had a hearing dysfunction in her right ear. She sent her to Dr. Eugen Grabscheid, an audiologist, who confirmed that she had a mild case of Ménière’s disease, a permanent buildup of fluids in the inner ear, a potentially dangerous, difficult-to-treat ailment that led to hearing loss and bouts of dizziness. —"Joe & Marilyn: Legends in Love" (2014) by C. David Heymann

Dinner With DiMaggio: Memories of an American Hero promises a rare glimpse into the private life of a frequently misunderstood man, and although occasionally prone to sensationalism, for the most part it delivers. Joe met his first wife, showgirl Dorothy Arnold, on a film set. Their son, Joe DiMaggio Jr., was born in 1941, but the couple were soon embroiled in a bitter divorce. “Dorothy was always trying to get between my little guy and me,” Joe told his friend Dr. Rock Positano. Although he was a lifelong movie fan, Joe’s brushes with Hollywood left him unimpressed. In the late 1940s, he was dining at the Stork Club with some of the biggest names in the movie industry, including Marlene Dietrich and the Bogarts. “I knew better than to pry,” Positano says, claiming that Joe gradually opened up. “He also spoke with [lawyer] Morris Engelberg about Marilyn,” he adds, “but I never knew what he told each of us, and Morris and I never compared notes.”

Joe thought Marilyn was both beautiful and “highly intelligent,” as Positano revealed in a recent interview for People magazine. “He had a tremendous amount of respect for Marilyn because she was a really great actress.” Nonetheless, her star was rising when she married Joe, and babies seem not to have been an immediate priority. His jealousy, and her ambition, were more likely causes of the split. When crowds gathered to watch her standing over a subway grate during filming of The Seven Year Itch, columnist Walter Winchell dragged a reluctant Joe along. The couple separated shortly afterward. “Doc, Marilyn told me that no man ever satisfied her like I did,” Joe said. Although respectful in public, Joe apparently took a dim view of her third husband, Arthur Miller. Sinatra told Joe that Marilyn kept a photo of him hidden in a closet, which “drove Miller crazy and right to the divorce court.” In the final years of her life, Marilyn grew close to Joe again. Talk of reconciliation was rife, but she insisted they were just good friends. Joe had probably been hurt by Marilyn’s relationship with Frank Sinatra, but by 1962, when her alleged involvement with John F. Kennedy occurred, the president had distanced himself from Sinatra. Positano repeats the tale of Joe snubbing Bobby Kennedy at Yankee Stadium in 1965. Marilyn had a long history of depression, and was addicted to sleeping pills. Joe told Positano that she would sometimes neglect her appearance. “Though Joe saw Marilyn’s behaviour become erratic, he was unsophisticated about mental illness,” Positano reflects. During his final trip to New York in 1999, a frail Joe was in a nostalgic mood. “I miss Marilyn more than ever,” he confided. One of his proudest achievements was the opening of the Joe DiMaggio Children’s Hospital in Florida.

One of Lee Strasberg’s standard suggestions—practically a requirement—was that students enhance their reservoir of primal memories and emotions (what he called “sense memory”) by entering psychoanalysis. He and Paula were undergoing analysis, and both felt, among its other advantages, that it had strengthened their marriage. Turning to Milton Greene for advice on the subject, Marilyn was soon given a referral. Greene himself had been in therapy for several years with Dr. Margaret Herz Hohenberg, who, like Lee Strasberg, had come to the United States from Hungary. A follower of the Viennese school of psychoanalysis founded by Sigmund Freud, Hohenberg, at fifty-seven, was a tall, heavy woman with white hair that was often braided and wrapped around her head. On Milton Greene’s recommendation, Marilyn met with the analyst. By March 1955, she was seeing Margaret Hohenberg five times a week.

Monroe’s presence on the block did not go unnoticed; Hohenerg’s neighbors would frequently stop her on the street and inquire, “How is Miss Monroe doing today?” During their sessions, for which Marilyn invariably arrived late, they dealt with the traumas of Monroe’s chaotic childhood, her lack of self-esteem, her lust for approval, her dread of rejection, her obsessive search for a father figure. To facilitate the analytic process, the actress recorded her thoughts and dreams in a series of binders that, in 2010, were posthumously published as a single volume called Fragments, which seemed an appropriate title considering Hohenberg’s pronouncement, made soon after she met Marilyn, that the actress possessed “a fragmented mind.” Typical of Marilyn’s nightmarish notations in Fragments is one that reads: “For Dr. H—Tell her about that dream of the horrible, repulsive man—who is trying to lean too close to me in the elevator—and my panic and then my thought despising him—does that mean I’m attached to him? He even looks like he has a venereal disease.” After six months of treatment, Hohenberg diagnosed Monroe as suffering from borderline personality disorder, a psychological condition characterized by intense turmoil and instability in relationships and behavior.

Marilyn demonstrated two of the conditions commonly associated with Borderline Personality Disorder: dissociation and depersonalization. Under stress, her mind and body would literally shut down, which helped explain (at least to Hohenberg) why Marilyn was always late for appointments and had difficulty remembering her lines when appearing in films. Strangely enough, Hohenberg also determined that Marilyn had a hearing dysfunction in her right ear. She sent her to Dr. Eugen Grabscheid, an audiologist, who confirmed that she had a mild case of Ménière’s disease, a permanent buildup of fluids in the inner ear, a potentially dangerous, difficult-to-treat ailment that led to hearing loss and bouts of dizziness. —"Joe & Marilyn: Legends in Love" (2014) by C. David Heymann

A 2013 study published in the journal Hippocampus found that daily sexual activity was not only associated with generation of more new neurons, but also with enhanced cognitive function. Research on humans has yielded similar findings. It turned out that both men and women who had engaged in any kind of sex over the past year had higher scores on the word recall test. Furthermore, for men only, being sexually active was linked to better performance on the number sequencing task. The results revealed that women who engaged in more frequent sexual intercourse had better recall of abstract words on the test. A new study out this year (also in the Archives of Sexual Behavior) that involved 6,000 adults age 50 and over explored how sexual frequency was associated with performance on two episodic memory tasks administered two years apart. Participants who had sex more often had better performance on the memory test. It's worth noting that more emotional closeness during sex was linked to better memory performance, too. As always, more research is necessary, especially research that can help to establish cause-and-effect in humans and that explores what actually happens in the brain in response to frequent sex. That said, the overall pattern of findings to date is consistent with the idea that sex may very well be beneficial for our brains and our cognitive performance. Source: www.psychologytoday.com