Buddy Holly is often underestimated. The sentimental veneer of his music belies his underlying emotional resiliency, his passion for beauty, and his consummate control. The story of rock and roll is the tale of outsiders gaining control of an entertaiment mechanism in order to extract from it personal significance (which is the only way to achieve mass significance). Buddy Holly never talked too much, he listened, and he was a very bright guy. Onstage, he was uninhibited; offstage, he was quiet, shy and withdrawn even with friends. Buddy Holly didn't inspire the ecstatic adoration than Elvis did, nor was he able, like Chuck Berry, to stay above the fray and comment upon it. Holly was always in the struggle himself. Never sure if his success would last, he sought something permanent—something that would indeed last "through times till all times end." Love gave him that sense of permanence. Buddy Holly's life was an enactment of the American Dream, and his music mirrored this spirit. For Buddy Holly, the promises might have failed in the past, but he still hoped for the best, even when it was unrealistic to expect it. —"Remembering Buddy: The Definitive Biography of Buddy Holly" (2001) by John Goldrosen

I’d be sitting around the Sands, hanging out with all those guys or lounging in the steam room with a whole other pocket of people—Frank Sinatra, Gregory Peck, Don Rickles. Today it’s hard for people to get an idea of how incredible Vegas was in those days, the kind of intensity that existed there. The sense of fashion, the sense of klieg-light visibility the casinos stimulated. I don’t think there’s ever been anything quite like Vegas in its golden era. Today, Vegas is this huge Disneyland for grown-ups where you get all these spectacles thrown at you with no real heart and soul, none of the real magic of what Vegas was back then. The type of people that run the casinos today are a different kind of animal altogether. Today it’s all corporate, which means lawyers and contracts and fine print. Eventually, I made it into the innest in crowd there ever was: The Rat Pack. I got to live the high wild life—something I’d only dreamed of back in Ottawa.

All the established songwriters of the day—Cole Porter, Sammy Cahn, and Irving Berlin—were busy writing songs for crooners like Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, and Perry Como. They weren’t about to start writing songs for me, that’s for sure. Anyway, these guys hated rock ’n’ roll, since they thought it was the death knell for most crooners. Overnight it was a brash new world, but they figured it was just a novelty sensation that would go away. Rock ’n’ roll had made serious inroads into the charts by the late fifties, but it wouldn’t be until the British Invasion in the early sixties that the big band singer became obsolete—except in Vegas, but then Vegas is another country. It took almost ten years for rock to take over the charts. Even if you were famous like Elvis, there just weren’t many writers out there writing rock ’n’ roll songs. Those who pioneered the rock ’n’ roll revolution—Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis—had mainly written their own songs. The only guys writing pop and rock ’n’ roll songs for other people in the fifties were the Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller duo, and the inimitable Doc Pomus.

In 1957 I played "Diana" to Chuck Berry and he threw me out of the room. “Listen, kid, let me give you a bit of advice, quit what you’re doing and get a real job.” Undaunted, I went over to see Fats Domino, who was in his dressing room, hoping for some better luck. I said, “Mr. Domino, I’ve got a song for you.” Domino listened to “Diana.” He looked at me quizzically and then beamed in that way Fats did, flashing his big teeth. “Now that’s sincere,” he said: “Not my kinda thing, son, not a song I could sing, understand? I’m old.” He advised to me: “If you want people to hear that song, you best record it yourself.” A year later, “Diana” was number one in the United States. I was hardly a pretty boy. When you’re unsophisticated, your expression is raw, raw but pure. I wasn’t afraid to sing “I’m just a lonely boy.” Clyde McPhatter, the lead singer of The Drifters, was insanely jealous of my success. He was a bitter, angry guy for someone who sang such sweet songs.

I was even different from the Southern guitar-slinging white boys, Buddy Holly (from Lubbock, Texas) and Eddie Cochran (who was born in Minnesota, but his parents came from Oklahoma). I was pretty damn sure of myself—had to be, to survive in that atmosphere. You can see a bit of the Anka alien in the film Lonely Boy, the 1962 documentary directed by Roman Kroitor and Wolf Koenig, especially in that scene in the station wagon where I’m sitting there, totally cool, calm, and affectless with people yapping away all around me. It’s an odd scene for somebody all of twenty-one, even I have to admit—but if I hadn’t had that kind of self-control I’d never have made it. No rock star today would stand for what we put up with on those horrible buses on tour. Those rock ’n’ roll tours would run as long as eighty days, we’d do as many as seventy cities—nobody got any sleep. After you’d sit on the bus for hours on end, looking at cornfields, you’d get to a broken-down theater where you’d line up next to each other in the crummy dressing rooms with your pomade and your hair dryer, hanging your suits in the shower to steam them out. I don’t know how we didn’t blow the electricity with all those hair dryers going at the same time. It was hard work, but we had nothing to compare it to.

Eddie Cochran was a typical rock ’n’ roller from California, but had the same aspects as the Southern guys. He was a quasi-cowboy, a cool cat. He had that swagger about him, the James Dean look. Eddie Cochran had his first hit “Sittin’ in the Balcony” and then had been in the movie The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) by Frank Tashlin. Eddie Cochran kind of mumbled like Marlon Brando and James Dean, and was fun to be around, a delight. He was a ladies’ man, and a good-time party guy. Buddy was tight with Eddie Cochran. They had a lot in common, except the drinking and womanizing. But Jerry Lee Lewis was off the charts. I can’t even explain how abusively unpredictable this guy could be. His whole lingo and attitude were redneck obnoxious—it was just nothing like I’d ever seen before. Buddy Holly was the only one who knew how to deal with Jerry Lee. Buddy was utterly unshockable—Jerry Lee’s behavior didn’t faze him one bit. Sometimes Buddy would fish Jerry Lee, totally soused, out of bars, drag him back to the hotel, put him under the shower, and get him to the theater on time.

Bobby Darin’s real name was Walden Robert Cassotto. He wasn’t exactly a pretty boy. He had the rugged good looks of a bulbous-nosed, crooked-mouthed hood, but still attractive—a John Garfield type. Like me, Bobby sprang from obscurity in 1958 and became famous with a recording of one of his own compositions, a rock ’n’ roll ditty called “Splish Splash.” Later on he made a hip transition with “Mack the Knife,” from Kurt Weill’s Threepenny Opera. Louis Armstrong had made a successful recording of it a few years earlier. Darin used to say, “The only person I loved until I met my wife Sandra Dee was my mother, and she died.” He’d been brought up by his grandmother, a vaudeville singer, and he learned at age thirty-two that Giovannina Cassotto, who he thought was his elder sister, was actually his mother.

Buddy Holly was an entirely different story. He had a soft shyness about him. He was a country boy, very raw, simple, modest, and sensitive. A very straightforward kind of guy. I was impressed with his guitar-driven sound and he respected what I did as a songwriter. In the beginning I was Buddy Holly’s nemesis. Buddy and I were neck-and-neck all the way with our hits “That’ll Be the Day” and “Diana.” He’d look at my picture in record-shop windows and say, “Who is this kid Anka, pushing me off the charts?” Like me, Buddy Holly wrote his own songs so he wasn’t dependent on outside writers like Boudleaux and Felice Bryant, who wrote the Everly Brothers’ songs. Buddy also had his own group, The Crickets; he didn’t play with pickup bands like the Everlys. We were all buddies, but those guys had that country-western, Southern clique thing going, and at the end of the day were in a bag all of their own. The difference between me and the Southern boys was that I wasn’t a guitar player, I had no idea where all of that was going, that guitar-driven rock sound. But in 1957, who could have guessed the next wave of rock and roll would be wailing electric guitars. The incredible sound that Buddy got on his guitar was the secret ingredient he passed on to The Beatles and The Rolling Stones—he was very influential with everybody in the next generation.

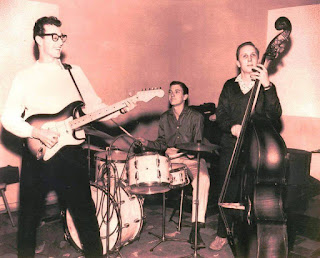

The influence of his Fender Stratocaster sound was where his genius lay. In Britain they’d never seen anything like it. They thought it was an outer-space guitar. English kids found his guitar sound sexy, and the glasses only added to his friendly appeal. And then there was that great hiccupy way he sang, “Love like yours will surely come my way, A-hey, A-hey-hey.” His ’55 Stratocaster got stolen on that British tour and he had to finish it with a blond Gibson. In comparison, Elvis was a different animal altogether—blunt, rough, and sex-charged. Their look couldn’t have been more different. There was no overt sexuality with Buddy like there was with Elvis. Buddy was also a singer-songwriter and that was the big difference between Elvis the entertainer and Buddy the confessional storyteller. That was the key change for The Beatles or The Stones, so Buddy’s influence in the end was more far-reaching than Elvis’s. Surely, Elvis was a larger-than-life CinemaScope American image. But Buddy provided the scaled-down guitar-band blueprint for most of the ’60s bands, especially in Great Britain. Buddy Holly loved my song “You Are My Destiny” with its big Don Costa production. He was looking for something different in his career. “I need to change my arrangements and try what you’re doing with your songs.” He wanted to leave The Crickets and move on. He asked me to write a song with him: “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore.” The whole focus of “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” was to do it with a big band, with violins and horns, a big, plush orchestral sound that would frame his voice, impart a more romantic aura to his songs.

It was crazy how much touring we all did, but who knew if it was going to last? The critics were saying that rock ’n’ roll was a novelty and would quickly fade away. Believe it or not, it could have easily happened that way—there were very few places where rock ’n’ rollers could perform. Jerry Lee Lewis was just a nightmare. I didn’t like him and he hated me. We fought constantly. He was spewing venom at me at 25,000 feet crossing the Pacific Ocean. We were fighting and yelling and throwing things at each other. Admittedly I was this annoying young brat, and it was especially grating to him that I had all these hit records. He loved to pick on me, saying I looked like a squashed-down Danny Thomas. I wasn’t too shy about shoving it in his face that I was higher in the charts than he was. There were pillow fights on the plane to Australia. Pop heartthrob vs. the Killer, round one. Although Buddy and The Crickets had three hits in Australia (“That’ll Be the Day,” “Oh, Boy!,” and “Peggy Sue”), Jerry Lee demanded his name be bigger than anyone else’s on the bill. Buddy said that was okay with him, but in the end my name got top billing, which really rankled Jerry Lee. Buddy started to steal the show in Australia, emerging at the forefront.

Unlike today, these guys were true song-pluggers, who went out and worked their catalog and had a sensitivity to the material. That’s how you got records made then. Now the recording/publishing business is more like the banking business. When we got back from our big Australian tour, Irvin Feld signed us up to do Alan Freed’s Big Beat Show at the Brooklyn Paramount Theatre from March 28 through May 1958. No Jerry Lee, but me, Buddy Holly, and The Everly Brothers joining up again with Chuck Berry, Clyde McPhatter and The Drifters. After we did that show, Alan Freed, the disc jockey, wanted to manage me. In those days, you could be a disc jockey and manage someone. Different set of rules back then. There’s a definite conflict of interest there, but the business was looser. Freed was a kind of forceful, tall, imposing-type guy. He was a true innovator in radio programming, but he ended up a kind of a tragic figure, getting caught up in the payola scandal. In those days, everybody did it—you could barely walk into the Brill Building without seeing someone handing a DJ a big envelope. But Freed got nailed as the fall guy for the payola practice.

Buddy Holly was getting even more dissatisfied with The Crickets: he wanted to go out on his own, he was outgrowing them. I saw that Buddy had an amazing future ahead of him. We became close, tight friends. We got to the point where we were talking about writing songs together and combining our different strengths as songwriters and producers, creating a situation where we could work together. We planned to start a publishing company together. By the end of the all-star tours we were separating ourselves out from the rest of the pack. During much of the time I knew him, Buddy was involved in some form of litigation with his manager (over money issues), and disputes with The Crickets (over the direction the band was going). Sometime that fall, after I got back, Buddy called Irvin Feld and me. He was sounding a bit desperate. He’d broken up with The Crickets and was having problems with his management. He told us he was out of money, and was going through problems with Norman Petty, who had apparently stolen money from him and his band. While he was away and before he could explain what he was doing, The Crickets had sided with his manager and Buddy felt betrayed. He had married this woman he’d met in New York, Maria Elena—she was the secretary at his record company—and wanted to move there. Buddy said he needed money fast, so we created a parallel tour to the one we were on, just for Buddy.

The tour was called the Winter Dance Party, just some name to make it sound lively and fun because it was in the middle of the winter and it was way out in these remote ballrooms and arenas in the Midwest. It was Buddy, the Big Bopper, Ritchie Valens and Dion. Waylon Jennings was Buddy’s bass player at that point—I think Buddy was paying him 75 bucks a week, and incidentally he never got paid for that tour. In 1958, Buddy went into the studio to record what turned out to be his final hit, “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore.” I really loved the way it came out. Dick Jacobs, the musical conductor at Decca studios, got his copyist to quickly write the lead sheets from Buddy’s guitar version. They wrote the arrangements for strings and rhythm very quickly. When I got to the studio there was this eighteen-piece orchestra, including eight violins, two violas, two cellos, and a harp, as well as string players recruited from the New York Symphony Orchestra. These were top session players, like Al Caiola and Abraham “Boomie” Richman from the Benny Goodman Band on tenor sax. Buddy sang it in his classic up-tempo Texas voice. His characteristic “buy-bees,” “golly-gees,” and hiccuppy vocals were so infectious and worked so well against the lush orchestration that, when he finished, he got a round of applause from those initially dubious studio musicians.

Buddy Holly talked about his new wife, Maria Elena, endlessly. Maria Elena had wanted to come on the tour, but she was pregnant and throwing up, and Buddy wouldn’t let her. Buddy would tape songs for her on his Ampex tape recording machine at his apartment. He’d written the song “Maria Elena” for her, recorded a few years later by Altenor Lima in 1963. Buddy Holly’s story was that of love. He sang about what he knew and the pureness and the simplicity of his voice reinforced that sincerity. Elvis, on the other hand, performed his songs; he personalized them with his own theatrical delivery, but by the sixties this type of song interpreter had become less convincing than groups and singers like Buddy writing their own material. Mostly, Buddy wrote in major keys: A, E, and D. That was Buddy’s magic sound.

Buddy’s vibe was always very upbeat, optimistic. He was happy he’d finally gotten rid of Norman Petty. He wasn’t the only one with problems with his manager. Don and Phil Everly were fighting their ex-manager over money, too. When I think of the difference between the way the fans saw me and the way they saw Buddy Holly, I feel it was because his approach was so personal. Buddy laid down a vibe that was unique to him. Straightforward, no technology. One microphone for him, one in front of the band, period. Nothing like it's made today. Buddy had grown up in poverty, wearing Levis and T-shirts, but now he was getting to be a real spiffy dresser. When Buddy talked about all the plans he had for a new studio and his European tour, he was just bursting with energy and optimism. One of the reasons Buddy took the plane on that fateful night was because of the way General Artists Corporation had planned the tour, without any logic to the geography. The crash that killed Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper was such a monumental disaster that left an unfillable gap in rock ’n’ roll. Time really seemed to just stop. Buddy Holly’s death left a big hole in my life, an enormous silence. The one thing I’ve learned is that great pop songs never go away. The influence of the ’50s carries on today. —"My Way: An Autobiography" (2013) by Paul Anka

I was even different from the Southern guitar-slinging white boys, Buddy Holly (from Lubbock, Texas) and Eddie Cochran (who was born in Minnesota, but his parents came from Oklahoma). I was pretty damn sure of myself—had to be, to survive in that atmosphere. You can see a bit of the Anka alien in the film Lonely Boy, the 1962 documentary directed by Roman Kroitor and Wolf Koenig, especially in that scene in the station wagon where I’m sitting there, totally cool, calm, and affectless with people yapping away all around me. It’s an odd scene for somebody all of twenty-one, even I have to admit—but if I hadn’t had that kind of self-control I’d never have made it. No rock star today would stand for what we put up with on those horrible buses on tour. Those rock ’n’ roll tours would run as long as eighty days, we’d do as many as seventy cities—nobody got any sleep. After you’d sit on the bus for hours on end, looking at cornfields, you’d get to a broken-down theater where you’d line up next to each other in the crummy dressing rooms with your pomade and your hair dryer, hanging your suits in the shower to steam them out. I don’t know how we didn’t blow the electricity with all those hair dryers going at the same time. It was hard work, but we had nothing to compare it to.

Eddie Cochran was a typical rock ’n’ roller from California, but had the same aspects as the Southern guys. He was a quasi-cowboy, a cool cat. He had that swagger about him, the James Dean look. Eddie Cochran had his first hit “Sittin’ in the Balcony” and then had been in the movie The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) by Frank Tashlin. Eddie Cochran kind of mumbled like Marlon Brando and James Dean, and was fun to be around, a delight. He was a ladies’ man, and a good-time party guy. Buddy was tight with Eddie Cochran. They had a lot in common, except the drinking and womanizing. But Jerry Lee Lewis was off the charts. I can’t even explain how abusively unpredictable this guy could be. His whole lingo and attitude were redneck obnoxious—it was just nothing like I’d ever seen before. Buddy Holly was the only one who knew how to deal with Jerry Lee. Buddy was utterly unshockable—Jerry Lee’s behavior didn’t faze him one bit. Sometimes Buddy would fish Jerry Lee, totally soused, out of bars, drag him back to the hotel, put him under the shower, and get him to the theater on time.

Bobby Darin’s real name was Walden Robert Cassotto. He wasn’t exactly a pretty boy. He had the rugged good looks of a bulbous-nosed, crooked-mouthed hood, but still attractive—a John Garfield type. Like me, Bobby sprang from obscurity in 1958 and became famous with a recording of one of his own compositions, a rock ’n’ roll ditty called “Splish Splash.” Later on he made a hip transition with “Mack the Knife,” from Kurt Weill’s Threepenny Opera. Louis Armstrong had made a successful recording of it a few years earlier. Darin used to say, “The only person I loved until I met my wife Sandra Dee was my mother, and she died.” He’d been brought up by his grandmother, a vaudeville singer, and he learned at age thirty-two that Giovannina Cassotto, who he thought was his elder sister, was actually his mother.

Buddy Holly was an entirely different story. He had a soft shyness about him. He was a country boy, very raw, simple, modest, and sensitive. A very straightforward kind of guy. I was impressed with his guitar-driven sound and he respected what I did as a songwriter. In the beginning I was Buddy Holly’s nemesis. Buddy and I were neck-and-neck all the way with our hits “That’ll Be the Day” and “Diana.” He’d look at my picture in record-shop windows and say, “Who is this kid Anka, pushing me off the charts?” Like me, Buddy Holly wrote his own songs so he wasn’t dependent on outside writers like Boudleaux and Felice Bryant, who wrote the Everly Brothers’ songs. Buddy also had his own group, The Crickets; he didn’t play with pickup bands like the Everlys. We were all buddies, but those guys had that country-western, Southern clique thing going, and at the end of the day were in a bag all of their own. The difference between me and the Southern boys was that I wasn’t a guitar player, I had no idea where all of that was going, that guitar-driven rock sound. But in 1957, who could have guessed the next wave of rock and roll would be wailing electric guitars. The incredible sound that Buddy got on his guitar was the secret ingredient he passed on to The Beatles and The Rolling Stones—he was very influential with everybody in the next generation.

The influence of his Fender Stratocaster sound was where his genius lay. In Britain they’d never seen anything like it. They thought it was an outer-space guitar. English kids found his guitar sound sexy, and the glasses only added to his friendly appeal. And then there was that great hiccupy way he sang, “Love like yours will surely come my way, A-hey, A-hey-hey.” His ’55 Stratocaster got stolen on that British tour and he had to finish it with a blond Gibson. In comparison, Elvis was a different animal altogether—blunt, rough, and sex-charged. Their look couldn’t have been more different. There was no overt sexuality with Buddy like there was with Elvis. Buddy was also a singer-songwriter and that was the big difference between Elvis the entertainer and Buddy the confessional storyteller. That was the key change for The Beatles or The Stones, so Buddy’s influence in the end was more far-reaching than Elvis’s. Surely, Elvis was a larger-than-life CinemaScope American image. But Buddy provided the scaled-down guitar-band blueprint for most of the ’60s bands, especially in Great Britain. Buddy Holly loved my song “You Are My Destiny” with its big Don Costa production. He was looking for something different in his career. “I need to change my arrangements and try what you’re doing with your songs.” He wanted to leave The Crickets and move on. He asked me to write a song with him: “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore.” The whole focus of “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” was to do it with a big band, with violins and horns, a big, plush orchestral sound that would frame his voice, impart a more romantic aura to his songs.

It was crazy how much touring we all did, but who knew if it was going to last? The critics were saying that rock ’n’ roll was a novelty and would quickly fade away. Believe it or not, it could have easily happened that way—there were very few places where rock ’n’ rollers could perform. Jerry Lee Lewis was just a nightmare. I didn’t like him and he hated me. We fought constantly. He was spewing venom at me at 25,000 feet crossing the Pacific Ocean. We were fighting and yelling and throwing things at each other. Admittedly I was this annoying young brat, and it was especially grating to him that I had all these hit records. He loved to pick on me, saying I looked like a squashed-down Danny Thomas. I wasn’t too shy about shoving it in his face that I was higher in the charts than he was. There were pillow fights on the plane to Australia. Pop heartthrob vs. the Killer, round one. Although Buddy and The Crickets had three hits in Australia (“That’ll Be the Day,” “Oh, Boy!,” and “Peggy Sue”), Jerry Lee demanded his name be bigger than anyone else’s on the bill. Buddy said that was okay with him, but in the end my name got top billing, which really rankled Jerry Lee. Buddy started to steal the show in Australia, emerging at the forefront.

Unlike today, these guys were true song-pluggers, who went out and worked their catalog and had a sensitivity to the material. That’s how you got records made then. Now the recording/publishing business is more like the banking business. When we got back from our big Australian tour, Irvin Feld signed us up to do Alan Freed’s Big Beat Show at the Brooklyn Paramount Theatre from March 28 through May 1958. No Jerry Lee, but me, Buddy Holly, and The Everly Brothers joining up again with Chuck Berry, Clyde McPhatter and The Drifters. After we did that show, Alan Freed, the disc jockey, wanted to manage me. In those days, you could be a disc jockey and manage someone. Different set of rules back then. There’s a definite conflict of interest there, but the business was looser. Freed was a kind of forceful, tall, imposing-type guy. He was a true innovator in radio programming, but he ended up a kind of a tragic figure, getting caught up in the payola scandal. In those days, everybody did it—you could barely walk into the Brill Building without seeing someone handing a DJ a big envelope. But Freed got nailed as the fall guy for the payola practice.

Buddy Holly was getting even more dissatisfied with The Crickets: he wanted to go out on his own, he was outgrowing them. I saw that Buddy had an amazing future ahead of him. We became close, tight friends. We got to the point where we were talking about writing songs together and combining our different strengths as songwriters and producers, creating a situation where we could work together. We planned to start a publishing company together. By the end of the all-star tours we were separating ourselves out from the rest of the pack. During much of the time I knew him, Buddy was involved in some form of litigation with his manager (over money issues), and disputes with The Crickets (over the direction the band was going). Sometime that fall, after I got back, Buddy called Irvin Feld and me. He was sounding a bit desperate. He’d broken up with The Crickets and was having problems with his management. He told us he was out of money, and was going through problems with Norman Petty, who had apparently stolen money from him and his band. While he was away and before he could explain what he was doing, The Crickets had sided with his manager and Buddy felt betrayed. He had married this woman he’d met in New York, Maria Elena—she was the secretary at his record company—and wanted to move there. Buddy said he needed money fast, so we created a parallel tour to the one we were on, just for Buddy.

The tour was called the Winter Dance Party, just some name to make it sound lively and fun because it was in the middle of the winter and it was way out in these remote ballrooms and arenas in the Midwest. It was Buddy, the Big Bopper, Ritchie Valens and Dion. Waylon Jennings was Buddy’s bass player at that point—I think Buddy was paying him 75 bucks a week, and incidentally he never got paid for that tour. In 1958, Buddy went into the studio to record what turned out to be his final hit, “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore.” I really loved the way it came out. Dick Jacobs, the musical conductor at Decca studios, got his copyist to quickly write the lead sheets from Buddy’s guitar version. They wrote the arrangements for strings and rhythm very quickly. When I got to the studio there was this eighteen-piece orchestra, including eight violins, two violas, two cellos, and a harp, as well as string players recruited from the New York Symphony Orchestra. These were top session players, like Al Caiola and Abraham “Boomie” Richman from the Benny Goodman Band on tenor sax. Buddy sang it in his classic up-tempo Texas voice. His characteristic “buy-bees,” “golly-gees,” and hiccuppy vocals were so infectious and worked so well against the lush orchestration that, when he finished, he got a round of applause from those initially dubious studio musicians.

Buddy Holly talked about his new wife, Maria Elena, endlessly. Maria Elena had wanted to come on the tour, but she was pregnant and throwing up, and Buddy wouldn’t let her. Buddy would tape songs for her on his Ampex tape recording machine at his apartment. He’d written the song “Maria Elena” for her, recorded a few years later by Altenor Lima in 1963. Buddy Holly’s story was that of love. He sang about what he knew and the pureness and the simplicity of his voice reinforced that sincerity. Elvis, on the other hand, performed his songs; he personalized them with his own theatrical delivery, but by the sixties this type of song interpreter had become less convincing than groups and singers like Buddy writing their own material. Mostly, Buddy wrote in major keys: A, E, and D. That was Buddy’s magic sound.

"Keep on shining on" (2009), The Buddy Holly Tribute song by The Crickets Sound Project: recorded and performed by Pete Carroll.