Dr. Thomas J. West: I think that Ozark is significantly more interesting than Breaking Bad. It’s not that I don’t like Breaking Bad. In fact, like so many other viewers, I found myself utterly transfixed by Bryan Cranston’s performance as Walter White, the school teacher who turns to cooking high-grade meth to help pay his medical bills and begins a slide into moral depravity. And it has to be said that in some ways Ozark is a bit derivative of Breaking Bad (though it’s also fair to point out that Breaking Bad was itself derivative of other crime dramas that preceded it). Like its predecessor, it focuses on a mild-mannered man who gets increasingly caught up in the world of drug cartels and money laundering. Marty flees to the Ozarks with his wife Wendy and their two children Jonah and Charlotte to set up a new series of money laundering operations for his drug cartel overlords, as they get further sucked into the criminal vortex.

For far too much of its run, Breaking Bad seemed to work overtime to make Walter White's wife Skyler into the sort of castrating bitch stereotype that is all-too-common in premium cable dramas focused on the “struggles” of deeply dysfunctional men. Ozark, however, takes a very different approach to the question of criminality. To start with, Bateman’s Marty is no Walter White. Though Bateman does have moments of intensity, for the most part he’s a far colder personality, more cerebral and ultimately less hubristic than Walter ever was. More than that, though, the series seems genuinely invested in its female characters and how they contend with changing fortunes of the Byrdes.

One of the fascinating things about this show is the fact that Marty and Wendy, despite everything, do seem to genuinely love one another, and there is never any question that they also love their children and will do anything to protect them. By the time that we get to the 3rd season, Wendy’s own sense of what is best for her family has begun to diverge sharply from Marty’s, in part because, when it comes right down to it, she’s more ambitious than he is. Whereas a show like Breaking Bad, with its relentless and cloying interest in Walter’s toxic masculinity, would paint such ambition as deviant and dangerous, in terms of the narrative it is Wendy’s ambition that keeps things rolling forward and, strangely enough we in the audience find ourselves wanting her to succeed. She’s the antihero that we’re led to cheer for her as she steadily keeps up with Marty, forging alliances with unscrupulous billionaires (and then betraying them), manipulating politicians to get a casino gambling license approved, and cozying up to Navarro.

Marty is a long way from Walter White. And as played with intriguing opacity by Jason Bateman, those differences are what helps Ozark find its own rhythm. The horror of Breaking Bad was its reveal of the murderous, greedy megalomaniac hiding beneath the surface of a seemingly mild-mannered chemistry teacher. In Ozark, our antihero never deliberately kills anyone, never plots anybody’s death and never really changes from the slightly wonkish number-cruncher we meet at the beginning of the first season. We’re not even sure if he’s actually evil—if anything, Ozark’s horror is that the audience doesn’t know precisely how to feel about this wholly anonymous nobody. In Arrested Development, Michael Bluth was always confident in the fact that he was brighter than all the spoiled idiots in his family—a realization that often led to laughs when his overconfidence resulted in his own comedic undoing. Marty carries that same edge of superiority into every scene he enters, especially when he lands in the Ozarks, using his polite, unthreatening manner to sweet-talk failing local-yokel business owners into selling their shops, presenting himself as an “angel investor” whose financial acumen can turn their stores around. Marty is the very model of a blank-slate financial planner: He’s got a head for numbers and is adept at convincing people to trust him, but he seems so devoted to logic that he’s almost entirely programmed out anything about himself that might be human. Marty justifies his potential involvement with the cartel by explaining flatly, “I wouldn’t be a mule, I wouldn’t be a dealer — I’d be just pushing my mouse around my desk.”

That kind of rationalization is how he handles everything in Ozark. Walter White built his meth empire to feed his need for power, getting off on being the badass after decades of feeling like an ineffectual loser. Marty does nothing out of emotion or for his ego—everything is executed with the bloodlessness and cold efficiency of a keystroke. As Marty’s life gets more complicated in Ozark and different people want him dead, he doesn’t discover a newfound, darker persona or get a taste for killing. In fact, Marty never once even mentions the idea of bumping off any of his many adversaries—a move that Walter White and other characters have discovered is a handy way of getting out of tight spots. Marty is too buttoned-down to ever consider something so heinous. If he’s indeed evil, it’s the kind that’s a lot less showy.

Sure, he may launder drug dealers’ millions, but Marty is not a monster, os is he? In the aftermath of

Breaking Bad, there’s been a lot of talk about why we watch (and maybe even root for) dastardly characters, and the answer is usually that because they’re such nuanced, compelling figures we become magnetized by their contradictions and mixture of charm and malice.

Ozark challenges that assumption by giving us an antihero so plainly ordinary that there’s no sheer glee or revulsion in watching Marty try to outfox his foes. When Mason tells Marty, “There’s gotta be a god, because there’s the devil. I think you’re the fucking devil.” That statement is a shock to Marty—and maybe the audience too. At the height of his power, Heisenberg arrogantly demanded to his underlings, “Say my name.” But most monsters aren’t like that—more often, they’re like Marty, who hopes you don’t notice him at all. Source: medium.com

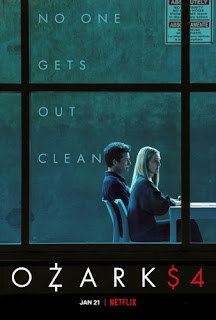

The Byrde family fans flocked to Netflix to watch “Ozark” Season 4, Part 1, drawing more viewers than any other TV series in its debut week. The first half of the final season of

Ozark landed at No. 1 on Netflix’s English-language TV Top 10 list for the week of Jan. 17-23, with 77 million hours viewed in just its first three days. One of the “Ozark” directors, Amanda Marsalis, revealed that Part 2 will drop sometime this May. So, we’re only a few short months away from the end of the Byrd family’s story. Netflix dropped the first seven episodes (Part 1) on Friday, Jan. 21. While Marty seems more jaded on Season 4, Wendy looks even more hardened and controlling. During one sparring session with Jonah, Wendy spits out, “You need to grow up. This is America. People don’t care where your fortune came from.” When trying to woo a potential business partner who’s wary of associating with money launderers, Wendy says, “It’s the only way to make the bad mean something: Bury it. Bury it. Pile good on top of good.” Clearly, Wendy is justifying her own actions this way. As the Byrdes expand from a typical upper-middle class family into a political power couple, they’re becoming more than an oddity; with their win-at-all-costs attitude, ever-deepening pockets, and lack of comeuppance for irrefutable wrongs, they represent the corruption rooted within USA.

One has to wonder if there’s enough truth in Wendy’s convictions to save her family; if her “go big or go home” attitude, paired with a loose moral compass, is just the thing that will get her out of trouble. This is America, and in America, powerful people with lots of powerful friends tend to make out OK. On the other hand, the Byrdes have been toying with folks—the Snells, the Navarros, etc.—who shoot first and worry about the clean up later. If Wendy keeps pissing people off, can she really expect her money, power, and privilege to insulate her from a bullet? And even if she does manage to survive, will she really be able to do enough good to bury the bad she’s already assembled? If she can save her life, can she also save her soul? When Part 2 hits, we’ll finally hear how much “Ozark” has still to say. The beginning of “The Beginning of the End”—the inevitable title of “Ozark’s” Season 4 premiere—flashes forward to a scene still not put in context by the time Part 1 comes to a close. Marty and Wendy are driving down the road, accompanied by their children, Charlotte and Jonah, as well as the smooth voice of Sam Cooke singing “Bring It On Home To Me.” A meeting with the FBI is mentioned. An event at their casino, the Missouri Belle, comes up. A clock is put, presumably, on their time left in Missouri: only 48 hours to go. As is prone to happen in the rare moments when the Byrdes are feeling good about things, disaster strikes. A car-carrier trailer is in the wrong lane, heading straight for the family minivan. Marty jerks the steering wheel to avoid a head-on collision, but the abrupt swerve sends their vehicle out of control. The crumpled van settles off-road, upside-down somewhere near the woods, and an eerie presence creeps over the area. Source: indiewire.com