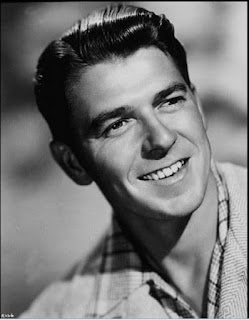

Son of the Midwest, movie star, and mesmerizing politician―America’s fortieth president comes to three-dimensional life in this gripping and profoundly revisionist biography. In this “monumental and impressive” biography, Max Boot, the distinguished political columnist, illuminates the untold story of Ronald Reagan, revealing the man behind the mythology. Drawing on interviews with over one hundred of the fortieth president’s aides, friends, and family members, as well as thousands of newly available documents, Boot provides “the best biography of Ronald Reagan to date”. The story begins not in star-studded Hollywood but in the cradle of the Midwest, small-town Illinois, where Reagan was born in 1911 to Nelle Clyde Wilson, a devoted Disciples of Christ believer, and Jack Reagan, a struggling, alcoholic salesman. Max Boot vividly creates a portrait of a handsome young man, indeed a much-vaunted lifeguard, whose early successes mirrored those of Horatio Alger. Reagan’s 1980 presidential election augured a shift that continues into this century. Boot writes not as a partisan but as a historian seeking to set the story straight. He explains how Reagan was an ideologue but also a supreme pragmatist who signed pro-abortion and gun control bills as governor, cut deals with Democrats in both Sacramento and Washington, and befriended Mikhail Gorbachev to end the Cold War. A master communicator, Reagan revived America’s spirits after the traumas of Vietnam and Watergate. With its revelatory insights, Reagan: His Life and Legend is no apologia, depicting a man with a good-versus-evil worldview derived from his moralistic upbringing and Hollywood westerns. Source: amazon.com

From dusty small-town roots, to the glitter of Hollywood, and then on to commanding the world stage, REAGAN (2024) is a cinematic journey of a great man overcoming the odds. Told through the voice of Viktor Petrovich, a former KGB agent who followed Reagan's ascent, REAGAN captures the indomitable spirit of the American dream. Starring Dennis Quaid, Penelope Ann Miller and Jon Voight.

Some big names on the entertainment circuit regularly dropped by Nancy Davis’s East Lake Shore Drive apartment. Spencer Tracy, chaperoned by Katharine Hepburn, came to visit “so often,” Nancy recalled, “that he practically became a member of the family”—and often to dry out; Walter Huston and his wife, Nan, moved in while they were starring in Dodsworth; Helen Hayes was a regular, as was Colleen Moore, Mary Martin, and Lillian Gish; Carol Channing brought Eartha Kitt. “Jimmy Cagney was always there,” Nancy recalled. Mary Martin, a longtime patient of Nancy's step-father Dr. Loyal Davis’s, was rehearsing Lute Song, a Broadway musical with Yul Brynner. There was a small part—a Chinese handmaiden—that suited Nancy’s nascent talents. Three weeks into rehearsal, however, the director disagreed. John Houseman found Nancy’s acting skills “awkward and amateurish” for a top-drawer Broadway production. “I suggested to the producer that she was not physically convincing,” recalled Houseman, who had been hired after Nancy joined the cast. He was told to take it up with Mary Martin. Fire Nancy Davis?—not a chance, Martin argued. Her bad back took precedence, and she wasn’t about to alienate her precious doctor by sacking his step-daughter.

On January 2, 1949, Nancy Davis got a call from her agent, informing her that “someone from Metro” had seen one of her TV appearances and suggested she fly out to Los Angeles for a screen test. Who that “someone” might be wasn’t a mystery. On and off, she had dated Benny Thau, MGM’s collegial vice president, who was said to have employed the practice of the casting couch. Though he was short, balding, and, at fifty-one, old enough to be her father, Nancy found in Thau an enthusiastic and supportive companion. No doubt his influence in Hollywood lent her countenance an attractive glow. However, despite an embarrassment of riches invested in her test, there was no heat on the screen. George Cukor was one of Hollywood’s A-list directors—MGM’s top director—who drew remarkable performances from his female stars. The scene Cukor chose for Nancy was from East Side, West Side, a high-priority studio project. He recruited hunky Howard Keel to read opposite her. It still didn’t add up to much. Cukor knew what a star looked like when he saw one. After watching a print of the finished test, “he told the studio Nancy had no talent.” In most cases, if a tastemaker of George Cukor’s esteem delivered such a verdict, the star-making machinery would have ground to a halt. But Thau had the power to veto the director’s opinion.

On March 2, 1949, MGM announced that the studio had given a seven-year contract to Nancy Davis at a starting salary of $300 a week. She was twenty-eight years old (dropped down to a more marketable twenty-six on the official document). One of her professional goals was snagging an eligible bachelor from among Hollywood’s leading men. Six months later, Ronald Reagan separated himself from the pack. During her Hollywood career, Nancy Davis dated many actors, including Clark Gable, Robert Stack, and Peter Lawford; she later called Gable the nicest of the stars she had met after Reagan. Dick Powell had been instrumental in securing Ronald Reagan a seat on the board of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG). Reagan later wote in his memoirs about Dick Powell, “I was one of the thousands who were drawn to this very kind man, and who would think of him as a best friend. Sometimes, our paths took us in different directions, and months would pass without either of us seeing the other. When we did meet again, it would be as if no interruption had occurred. I cannot recall Dick Powell ever saying an unkind word about anyone.”

When Nancy Davis met Ronald Reagan on November 15, 1949, he had risen to president of the SAG. She had noticed that her name had appeared on the Hollywood blacklist. Davis sought Reagan's help to maintain her employment in Hollywood and for having her name removed from the list. Reagan informed her that she had been confused with another actress. The two began dating and their relationship was the subject of many gossip columns; one Hollywood press account described their nightclub-free times together as "the romance of a couple who have no vices."

On March 10, 1947, three days before the Academy Awards ceremony, the board of the Screen Actors Guild met in a hastily called session to resolve a thorny jurisdictional problem. Because of a newly enacted resolution that prohibited members with production interests from serving on the board, Robert Montgomery, its president, announced his resignation, along with Jimmy Cagney, Dick Powell, Franchot Tone, and John Garfield. Replacement officers were pressed into immediate service, along with a vote to name Montgomery’s successor. George Murphy and Gene Kelly were nominated from the floor. Gene Kelly rose and placed Ronnie’s name in contention. Ronnie, as it happened, was conspicuously absent. He was attending a gathering of the American Veterans Committee, a group that linked veterans to potential employers, unaware that a consequential summit was taking place. When the vote was tabulated, the outcome was decisive. William Holden called later that night with the results. Ronald Reagan had been elected president of the Screen Actors Guild. The news delighted Ronnie. Whatever burden SAG had caused him, whatever turmoil in its ranks, deep down he loved the politics. He was as proud of the role he had played in the guild’s evolution as of any movie he had ever made.

The presidency of the Screen Actors Guild gave him the soapbox from which to launch an anticommunism campaign, and a faction of his membership was ready to ride sidekick. There had always been a predominantly conservative element at the top of the guild. Robert Montgomery, Dick Powell, Robert Taylor, Ronald Colman, George Murphy and Adolphe Menjou, among others, were determined to oust the leftist influence that they said corrupted Hollywood and was a threat to American ideals. They belonged as well to the Motion Picture Alliance, whose members included Gary Cooper, Ginger Rogers, John Wayne, Ward Bond, Charles Coburn, and ZaSu Pitts. The MPA’s charter made no bones about its ultimate goal. “In our special field of motion pictures, we resent the growing impression that this industry is made up of, and dominated by, Communists, radicals and crackpots,” it stated. “We pledge to fight any effort of any group or individual, to divert the loyalty of the screen from the free America that gave it birth.” The MPA set its sights on suspected sympathizers—“subversives,” as it labeled them. The Screen Actors Guild became a hotbed of infighting. On September 12, 1947, at a routine SAG board meeting, a proposal was raised that would require all SAG members to sign a loyalty oath. Ronnie felt it was self-defeating, and instead he proposed making the oath voluntary. It was passed after little debate. About the HUAC hearings, Reagan said: “It’s so simple. All you’ve got to do is just name a couple of names that have already been named.”

His divorce from Jane Wyman took Hollywood by surprise. “Such a thing was so far from even being imagined by me,” Ronnie later admitted. He had a more conventional outlook, the product of Midwestern expectations. In a town where marriage was the shakiest of propositions, the Reagan-Wyman union had seemed like a solid bet. It was almost as though the film community had a stake in its success. Friends like the Powells and the Hustons were disheartened by the news, but no one took it as badly as Ronnie. He was back in Eureka, Illinois, back as Dutch, for the weekend, visiting his old coach Ralph McKinzie and anointing the Pumpkin Festival queen, when the story broke in the local Illinois papers. It hit him, people said, “like a ton of bricks.” When he returned home, Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons circled like a pair of vultures. Louella, his longtime advocate, picked at him first. No match for her meddling, Ronnie poured out his heart, unmindful that the seal of the confessional didn’t apply. Indiscreetly, he admitted that Jane had told him she still loved him but was no longer in love with him. That distinction seemed beyond his grasp. Even so, he was willing to give her plenty of space, hoping it would reignite a flame. “Right now, Jane needs very much to have a fling,” he said. “And I intend to let her have it. She is sick and nervous and not herself.” Hedda Hopper piled on in a subsequent Modern Screen column that aired all the couple’s private affairs.

As early as 1940, with the world on the brink of war, Dick Powell had tried persuading Ronald Reagan to run for Congress on the Republican ticket. The likelihood of that happening, at the time, was low. Reagan's flag was still firmly planted in Democratic soil, and switching parties was unthinkable. It was a nonstarter in 1950 when someone put his name up as a candidate for mayor of Hollywood, an honorary position. That left a cheesy, tinsel aftertaste. Local Democrats had asked him to run for Congress in 1952. Not to be outdone, that same year, Holmes Tuttle, an influential Republican contributor and prominent L.A. businessman, proposed that Reagan seek a Senate seat. Reagan loved Roosevelt’s view that common people can have a vision that included all social classes for the good of the country. Reagan had even supported the election of Harry Truman, whom he admired. But, lately, he’d become disillusioned with the Democratic Party and its penchant toward “encroaching government control.”

Reagan deplored “the problems of centralizing power in Washington,” which he felt took inalienable rights and freedoms away from citizens. To him, it seemed the party’s liberal faction also went to great lengths to defend the shady Hollywood clique that had romanticized and dabbled in communism. All this served to redirect Reagan’s political antennae. His closest friends—Dick Powell, Bill Holden, Robert Taylor and Bob Cummings—were steadfast Republicans who had tirelessly drawn him to their side. And he’d gone for Ike in 1952, the first time Reagan had ever voted for a Republican candidate. From the 1970s on, the movies had turned away from the old studio era. By the time he took office as President of the USA, the Hollywood dream factory had turned its gaze to stories of anti-heroes, moral ambiguity, cruelty, and violence. Ronald Reagan never liked those movies. The sex scenes embarrassed him, too. On the national stage, he tried to project the old-style moral certainty of the classics he loved.

The key to Reagan’s success, like that to Roosevelt’s, was his ability to restore Americans’ faith in their country. Reagan was called the “great communicator” with reason. He was the most persuasive political speaker since Roosevelt and Kennedy, combining conviction, focus, and humor in a manner none of his contemporaries could approach. Reagan’s critics often dismissed the role of conviction in his persuasiveness; they attributed his speaking skill to his training as an actor. But this was exactly wrong. Reagan wasn’t acting when he spoke; his rhetorical power rested on his wholehearted belief in all the wonderful things he said about the United States and the American people, about their brave past and their brilliant future. He believed what Americans have always wanted to believe about their country, and he made them believe it too. Reagan told stories and jokes better than any president since Lincoln. He understood the disarming power of humor: that getting an audience to laugh with you is halfway to getting them to agree with you. He was not a warm person, but he seemed to be, which in politics is more important. Many people loathed his policies, but almost no one disliked him personally.

Democratic elections are, at their most basic level, popularity contests, and Reagan knew how to be popular. Like Roosevelt and other successful presidents, he realized that progress comes in pieces. If he got four-fifths of his ask in a negotiation, he took it and ran. He knew he could return for the rest. Reagan’s timing—some called it his luck—was no less essential to his success than his ability. “I know in my heart that man is good,” Reagan had said at the dedication of his library. “That what is right will always eventually triumph.” These lines of the Reagan creed were etched over his grave at the Reagan Library. But the closing words of his poignant farewell to the American people were the ones that were better remembered, that captured the belief that made him irresistible to so many. The shadow of forgetfulness was growing long across his path, yet his optimism and faith in his country remained undiminished as he wrote, “I know that for America there will always be a bright dawn ahead.” —Sources: "Reagan: The Life" (2015) by Henry William Brands and "Ronald Reagan: An American Journey" (2018) by Bob Spitz

No comments :

Post a Comment