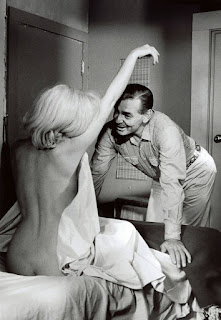

A nude scene long believed lost featuring Marilyn Monroe in John Huston’s The Misfits has been re-discovered. The footage, cut from the film by Huston, was previously believed to have been destroyed. The whereabouts of the footage was uncovered by Charles Casillo, the author of Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon. Casillo discovered that the footage had not been destroyed during an interview with The Misfits producer's (Frank Taylor) son Curtice Taylor, who revealed that he had kept in a locked cabinet since his father's death nearly twenty years ago in 1999. Living up to her sex symbol status, Monroe reportedly went nude while filming without warning, much to the chagrin of director, John Huston. Her impromptu disrobing was not appreciated by Huston, however, who felt it was unnecessary for the scene. Source: deadline.com

While Something's Got to Give (1962) is listed as Marilyn Monroe’s last film, The Misfits was her last completed movie before her death from a drug overdose in 1962. Bored while waiting for Monroe to arrive on the set, Clark Gable volunteered to do a number of hazardous routines which included being dragged by a truck travelling at 30 mph. On the last day of filming, he allegedly said, "Christ, I'm glad this picture's finished. She [Monroe] damn near gave me a heart attack." The next day, he suffered a massive heart coronary which led to his death eleven days later. According to Arthur Miller, Clark Gable had already seen a rough cut of the movie by the last day of filming, and said: "This is the best picture I have made, and it's the only time I've been able to act."

In his study on Marilyn Monroe, Graham McCann describes the character of Roslyn as having “the abstraction, and the intimacy, of a figure in a dream” (1988, p.155). Undoubtedly the film acknowledges the oneiric qualities of Monroe/Roslyn. Indeed, the vision of the movie as a whole seems to gesture towards an understanding of Monroe and her character as the ultimate misfit, an individual unable to completely find her place in either the ideal or the real. As Montgomery Clift’s character remarks: “I can’t figure you floating around here like this”; to which Roslyn replies: “I don’t know where I belong”. Clark Gable plays an aging cowboy whose life has lost purpose and who is reduced to capturing wild horses — the symbols of the free life he loved — for dog food. Marilyn/Roslyn is the only beautiful thing in the whole ugly desert, in the whole world, in this whole dump of toughness, atom bomb, death. Source: wcreynolds.com

Michelle Morgan, who has studied Marilyn Monroe’s life for 30 years, was able to track down some of the last living people associated with the screen legend to further investigate how the star helped pioneer an unlikely movement in Hollywood for other actresses yearning to make it without resorting to the casting couch. “She had said that she never fell for it,” Morgan told Fox News. In the mid-1950s, Monroe spoke out about being harassed by an executive whom she did not name. "She was very intelligent about that, to keep his name out of the article. But she certainly did speak about it," Morgan said. “She was never going to let herself be victimized. She spoke about it and as a result, inspired other people. She was one of the few actresses in Hollywood at that time who was speaking out about that.” Morgan added: “I think based on the things she said herself and the outspoken way she approached Hollywood, I personally don’t believe she was ever a victim of the casting couch. I think she was able to walk away." Arthur Miller said: “She was making fun of the situation as she was playing it. That was the difference. People thought they could imitate her by being cute. But she was being cute and making fun of being cute at the same time. There was another dimension, which is very difficult to do.”

Harassment in Hollywood wasn’t the only hot topic on Marilyn Monroe’s mind. Frustrated for constantly being cast in “dumb blonde” roles, Monroe wasn’t shy about letting the film studio know she was willing to risk her growing success just for the chance to play different characters. The scene in which Monroe’s white halter dress blows over her hips as she steps onto a New York subway grate while being ogled by 5000 onlookers made her an icon. And while some may believe the actress was exploiting her sex-appeal, Morgan said she was proud of making a bold statement. “I think she enjoyed the fact that she was an attractive woman who had an effect on other people. Not just on men, but on people around her… I thinks she really used the skirt scene… to get out of these dumb blond roles and… as a way of getting power because she worked so hard to get it… And at the end of the day, it was just a scene for a film. A very successful one.” Source: www.foxnews.com

In the summer of 2002 a book of photographs was published called Becoming Marilyn, featuring pictures taken in 1949 by photographer André de Dienes of a young model who was preparing to make the leap into Hollywood stardom. In reviewing Becoming Marilyn, Newsweek magazine commented that the book’s “images catching Norma Jeane as she mutates to ‘Marilyn.’” This statement reflects the basic premise of the myth of Marilyn Monroe: a real girl (named Norma Jean) metamorphosed into something that was not a person, but a concept: “Marilyn.” And it is an ideal seen as being distinct from the woman’s reality. “Marilyn” was only a fantasy of femininity, an imaginary role the actress performed with immense success, but which eventually destroyed her. Norman Mailer shows this response par excellence in his notorious, ranting catalog of Marilyn’s contradictions. She was, as Mailer describes her: a lover of books who did not read, a proud inviolate artist who could haunch over to publicity; a female spurt of wit and sensitive energy who could hang like a sloth for days in a muddy-mooded coma; a child-girl, yet an actress to loose a riot by dropping her glove at a premiere; a fountain of charm and a dreary bore; an ambulating cyclone of beauty and a dank hunched-up drab at her worst; lover of life and a cowardly hyena of death who drenched herself in chemical stupors... Simone de Beauvoir wrote that 'Woman is all that man desires and all that he does not attain'.” That's Marilyn. —"The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe" (2005) by Sarah Churchwell

Marilyn's Last Sessions (2013): A novel based on the records of Marilyn Monroe's analysis is grimly fascinating. The "last sessions" of the title are those that Marilyn had in the final two years of her life with the psychiatrist Ralph Greenson. In the 1950s Greenson, who had worked with Freud in pre-war Vienna, was at the top of his profession and highly regarded both by his psychoanalytical colleagues. In Michel Schneider's portrayal of Marilyn, she is deeply strange, part changeling, part demon, part lost soul. Marilyn's Last Sessions tells the story of a double tragedy. Marilyn was self-destructive, but also she was one of those people who damage anyone who comes too close. Jean-Paul Sartre said of her, "It's not just light that comes off her, it's heat. She burns through the screen." As the actress said herself, "I drag Marilyn Monroe around with me like an albatross". By late 1961, for Dr Greenson, Marilyn was both patient and ever-present family friend. Marilyn, he found, could not abide the notion of any imperfection in ‘certain ideal figures in her life.’ Greenson came up later with a more acute summation of her predicament: "she was an intellectual who shielded herself from the pain of thinking by talking in a little girl's voice and putting on a show of being dumb."

‘Marilyn could not rest until peace had been reestablished,’ Greenson wrote. But the psychiatrist thought her inability to handle anything she perceived as hurtfulness, along with her abnormal fear of homosexuality—Greenson was to write—‘were ultimately the decisive factors that led to her death.’ Marilyn herself told journalist W. J. Weatherby, ‘People tried to make me into a lesbian. I just laughed. No sex is wrong if there’s love in it.’ Earlier, speaking of her life in 1948, she said the sexual side of relations with men had so far been a disappointment. ‘Then it dawned on me,’ she said, ‘that other people, other women, were different than me. They could feel things I couldn’t. And when I started reading books I ran into the words “frigid,” “rejected,” and “lesbian.” I wondered if I was all three of them. There was also the sinister fact that a well-made woman had always thrilled me to look at.’ Source: www.theguardian.com

No comments :

Post a Comment