The day before Thanksgiving, Zelda Fitzgerald received a recording of F. Scott’s voice which delighted both her and Scottie. “It made me feel all safe in the center of things again and important.” She played it over and over. She told him she was busy writing, but “Fantastic exhuberance has deserted me and everything presents itself in psychological terms for novels.” On Thanksgiving Day after the turkey dinner at her mother’s she wrote Scott again: "It makes me remember all the times we’ve been together absolutely alone in some supended hour, a holiday from Time prowling about in those quiet place alienated from past and future where there is no sound save listening and vision is an anesthetic… My story limps homeward, 1,000 words to a gallon of coffee." -"Zelda: A Biography" (2011) by Nancy Milford

TURKEY REMAINS AND HOW TO INTER THEM WITH NUMEROUS SCARCE RECIPES

"At this post holiday season, the refrigerators of the nation are overstuffed with large masses of turkey, the sight of which is calculated to give an adult an attack of dizziness. It seems, therefore, an appropriate time to give the owners the benefit of my experience as an old gourmet, in using this surplus material. Some of the recipes have been in my family for generations. (This usually occurs when rigor mortis sets in.) They were collected over years, from old cook books, yellowed diaries of the Pilgrim Fathers, mail order catalogues, golf-bags and trash cans. Not one but has been tried and proven—there are headstones all over America to testify to the fact. Here goes:

1. Turkey Cocktail: To one large turkey add one gallon of vermouth and a demijohn of angostura bitters. Shake.

2. Turkey à la Francais: Take a large ripe turkey, prepare as for basting and stuff with old watches and chains and monkey meat. Proceed as with cottage pudding.

3. Turkey and Water: Take one turkey and one pan of water. Heat the latter to the boiling point and then put in the refrigerator. When it has jelled, drown the turkey in it. Eat. In preparing this recipe it is best to have a few ham sandwiches around in case things go wrong.

4. Turkey Mongole: Take three butts of salami and a large turkey skeleton, from which the feathers and natural stuffing have been removed. Lay them out on the table and call up some Mongole in the neighborhood to tell you how to proceed from there.

5. Turkey Mousse: Seed a large prone turkey, being careful to remove the bones, flesh, fins, gravy, etc. Blow up with a bicycle pump. Mount in becoming style and hang in the front hall.

6. Stolen Turkey: Walk quickly from the market, and, if accosted, remark with a laugh that it had just flown into your arms and you hadn't noticed it. Then drop the turkey with the white of one egg—well, anyhow, beat it.

7. Turkey à la Crême: Prepare the crême a day in advance. Deluge the turkey with it and cook for six days over a blast furnace. Wrap in fly paper and serve.

8. Turkey Hash: This is the delight of all connoisseurs of the holiday beast, but few understand how really to prepare it. Like a lobster, it must be plunged alive into boiling water, until it becomes bright red or purple or something, and then before the color fades, placed quickly in a washing machine and allowed to stew in its own gore as it is whirled around. Only then is it ready for hash. To hash, take a large sharp tool like a nail-file or, if none is handy, a bayonet will serve the purpose—and then get at it! Hash it well! Bind the remains with dental floss and serve.

9. Feathered Turkey: To prepare this, a turkey is necessary and a one pounder cannon to compel anyone to eat it. Broil the feathers and stuff with sage-brush, old clothes, almost anything you can dig up. Then sit down and simmer. The feathers are to be eaten like artichokes (and this is not to be confused with the old Roman custom of tickling the throat.)

10. Turkey à la Maryland: Take a plump turkey to a barber's and have him shaved, or if a female bird, given a facial and a water wave. Then, before killing him, stuff with old newspapers and put him to roost. He can then be served hot or raw, usually with a thick gravy of mineral oil and rubbing alcohol. (Note: This recipe was given me by an old black mammy.)

11. Turkey Remnant: This is one of the most useful recipes for, though not, "chic," it tells what to do with the turkey after the holiday, and how to extract the most value from it. Take the remants, or, if they have been consumed, take the various plates on which the turkey or its parts have rested and stew them for two hours in milk of magnesia. Stuff with moth-balls.

12. Turkey with Whiskey Sauce: This recipe is for a party of four. Obtain a gallon of whiskey, and allow it to age for several hours. Then serve, allowing one quart for each guest. The next day the turkey should be added, little by little, constantly stirring and basting.

13. For Weddings or Funerals: Obtain a gross of small white boxes such as are used for bride's cake. Cut the turkey into small squares, roast, stuff, kill, boil, bake and allow to skewer. Now we are ready to begin. Fill each box with a quantity of soup stock and pile in a handy place. As the liquid elapses, the prepared turkey is added until the guests arrive. The boxes delicately tied with white ribbons are then placed in the handbags of the ladies, or in the men's side pockets." —"The Crack-Up" (1945) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Thanks for the great American novels - List of favourite US fiction: The Great Gatsby (1925) by F Scott Fitzgerald. One of the most famous novels ever written, "The Great Gatsby" is about far more than one man’s deluded pursuit of the girl he once loved and clearly barely knew, it is the elegy of the American Dream. The prose is inspired, the images with their wasteland symbolism are chillingly exact and, above all, there is the disillusion conveyed by the narrator, Nick Carraway, the bewildered witness who is both intrigued and appalled by the excess and the cruelty. As a parable of innocence corrupted, The Great Gatsby, written by the doomed Fitzgerald at his most inspired, is difficult to surpass. Source: www.irishtimes.com

"Roxanne, standing beside, would lookintently at Jeff, dreaming that some shadowy recognition of this former friend had passed across that broken mind — but the head, pale, carven, would only move slowly in its sole gesture toward the light as if something behind the blind eyes were groping for another light long since gone out. These visits stretched over eight years — at Easter, Christmas, Thanksgiving, and on many a Sunday Harry had arrived, paid his call on Jeff, and then talked for a long while with Roxanne on the porch. He was devoted to her. He made no pretense of hiding, no attempt to deepen, this relation. She was his best friend as the mass of flesh on the bed there had been his best friend. She was peace, she was rest; she was the past. Of his own tragedy she alone knew." -THE LEES OF HAPPINESS by F. Scott Fitzgerald, published in "Tales of the Jazz Age" (1922)

One evening during Thanksgiving vacation, as they waited for dinner in the library of Christine Dicer’s house on Gramercy Park, Josephine said to Lillian: “I keep thinking how excited I’d have been a year ago. A new place, a new dress, meeting new men.” She paused for a moment. “Last night in bed I was thinking of the sort of man I really could love, but he’d be different from anybody I’ve ever met. He’d have to have certain things. He wouldn’t necessarily be very handsome, but pleasant looking; and with a good figure, and strong. Then he’d have to have some kind of position in the world, or else not care whether he had one or not; if you see what I mean. He’d have to be a leader, not just like everybody else. And dignified, but very pash, and with lots of experience, so I’d believe everything he said or thought was right. And every time I looked at him I’d have to get that thrill I sometimes get out of a new man; only with him I’d have to get it over and over every time I looked at him, all my life. I’d want to be always sure of loving him. It’s much more fun to love someone than to be loved by someone.” -EMOTIONAL BANKRUPTCY by F. Scott Fitzgerald, published in The Saturday Evening Post (1931)

Thursday, November 27, 2014

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Pre-Code for Holidays, The Women, Irving Thalberg & F. Scott Fitzgerald

Pre-Code Movies on TCM in December 2014 and Other Site News: As for the TCM Schedule, it’s unsurprisingly top heavy, with several Joan Crawford pictures, several Mae West and Cary Grant flicks, and even a couple of Warren William movies popping up all before the 3rd! There’s also a day filled with Edward G. Robinson pre-Codes (most of which I haven’t seen) on the 12th. Things peter out quickly, though, as TCM adjusts to be a bit more family friendly as the holiday approaches. The two quintessential pre-Code Christmas movies, Little Women and The Thin Man both get their bows around that time. So, hey, if you pick up the book, tune into TCM on the 20th and follow along! Source: pre-code.com

Robert Sklar argued that: "In the first half decade of the Great Depression, Hollywood's movie-makers perpetrated one of the most remarkable challenges to traditional values in the history of mass commercial entertainment." Sklar was writing in the early 1970s, when conventional wisdom suggested that few written records had escaped the studio shredder. Within a decade, however, film scholars gained access to several major archives containing a surfeit of documents detailing the bureaucratic operations of the Dream Factory. The Production Code Administration (PCA) Archive is one of the richest of these sources, describing the negotiations between PCA officials and the studios, movie by movie, script draft by script draft. In complete contradiction to the mythology of the Code not functioning during the early 1930s, its records reveal that this period actually saw by far the most interesting negotiations between the studios and the Code administrators over the nature of movie content, as the Code was implemented with increasing efficiency and strictness after 1930. Throughout the period, movie content was changed to conform to the Code's evolving case law.

A number of authoritative books - Lea Jacobs' The Wages of Sin, Tino Balio's Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, Ruth Vasey's The World According to Hollywood – have established quite unequivocally that the old account must be discarded, since it is demonstrably incorrect to suggest that movies made between 1930 and 1934 were “uncensored”. Individual recommendations might be disputed, often in hyperbolic language, but the Code's role in the production process was not a matter of contention, and studio personnel did not resist its implementation. Sklar's account of the Golden Age of Turbulence relied on an analysis of about 25 movies, or approximately one percent of Hollywood's total output of feature pictures between 1930 and 1934. The critical canon of “pre-Code cinema” to be found in the schedules of American Movie Classics, is now perhaps ten times that size.

The early 1930s is, indeed, one of Hollywood's Golden Ages of Turbulence, like the early 1970s and the early 1990s, when a combination of economic conditions and technological developments destabilised the established patterns of audience preference. As the Code's first administrator, Jason Joy, explained, studios had to develop a system of representational conventions “from which conclusions might be drawn by the sophisticated mind, but which would mean nothing to the unsophisticated and inexperienced”. Much of the work of self-regulation lay in the maintenance of this system of conventions, and as such, it operated, however perversely, as an enabling mechanism at the same time that it was a repressive one. The rules of both conduct and representation under these conditions were perhaps most cogently articulated by F. Scott Fitzgerald's Monroe Stahr in The Last Tycoon, explaining to his scriptwriters how the audience is to understand their heroine's motivation: "At all times, at all moments when she is on the screen in our sight, she wants to sleep with Ken Willard… Whatever she does, it is in place of sleeping with Ken Willard. If she walks down the street she is walking to sleep with Ken Willard, if she eats her food it is to give her enough strength to sleep with Ken Willard. But at no time do you give the impression that she would even consider sleeping with Ken Willard unless they were properly sanctified." Source: sensesofcinema.com

December 21, 2014, at 6:00 AM: THE WOMEN (1939) - TCM

A happily married woman lets her catty friends talk her into divorce when her husband strays.

Director: George Cukor Cast: Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, Paulette Goddard, Joan Fontaine, etc.

Writing credits (based on Clare Boothe Luce's play): Anita Loos, Jane Murfin, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Donald Ogden Stewart

Norma Shearer's beauty, hard work, down-to-earth charm and her marriage to Irving Thalberg, the film executive, made her a leading light of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios and a pillar of California film society. Miss Shearer kept some of her down-to-earth style in later years, even after Mr. Thalberg's death of pneumonia in 1937 had made her rich; he left her and their two children $4.5 million. Miss Shearer's popularity proved strong during her 20-year career, with many of the studio's plum roles hers for the taking, and approved by her husband. One example was the Lynn Fontanne role in the 1939 ''Idiot's Delight,'' opposite Clark Gable in the Alfred Lunt part. The movie was adapted from Robert E. Sherwood's antiwar play. She drew good reviews for another Broadway transition, ''The Women,'' and for ''Escape,'' a strong anti-Nazi drama co-starring Robert Taylor. Miss Shearer retired from the screen after making ''Her Cardboard Lover,'' which received poor notices in 1942. Source: www.nytimes.com

Irving Thalberg handed F. Scott Fitzgerald his new assignment: make Jean Harlow a star. Since "Red-Headed Woman" (1932) was an important picture, Eddie Mannix was present. Mannix, a former bouncer at Palisades Amusement Park and now a special aid to L. B. Mayer, was one executive who gave Fitzgerald trouble from the moment he entered MGM in 1931 to the moment he left for good in 1938. Ruling over the assembly, his thin knees drawn up beside him in his chair, was Thalberg himself. Everyone was there, except Jack Conway, the film’s director. “The directors did not appear at these showings,” Fitzgerald would later explain in The Last Tycoon, “officially because their work was considered done, actually because few punches were pulled here as money ran out in silver spools. There had evolved a delicate staying away.”

“Scott Fitzgerald is almost the only writer who never has cause to complain of his Hollywood welcome,” Dorothy Speare observed at the time. “He is famous even in Hollywood, where his meteoric arrivals and departures are discussed in film circles as avidly as they discuss themselves.” He was hired to help write a screen adaptation of Redheaded Woman (1931), a novel by his imitator Katharine Brush. Fitzgerald was faced with the problem of trying to write like a copy of himself, and it showed. As Fitzgerald later explained to his daughter: "Far from approaching it too confidently I was far too humble. I ran afoul of a bastard named [Marcel] de Sano, since a suicide, and let myself be gypped out of command. I wrote the picture and he changed as I wrote. I tried to get at Thalberg but was erroneously warned against it as 'bad taste.' Result—a bad script." Fitzgerald did eventually see Thalberg, but it was at Thalberg’s request; he had just read what Fitzgerald and his collaborator were preparing for Harlow, and he evidently smelled smoke once again. All that remains of the work which Fitzgerald did for Thalberg is an unfinished seventy-six page script, the one de Sano reworked. -"Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood" (1972) by Aaron Latham

Robert Sklar argued that: "In the first half decade of the Great Depression, Hollywood's movie-makers perpetrated one of the most remarkable challenges to traditional values in the history of mass commercial entertainment." Sklar was writing in the early 1970s, when conventional wisdom suggested that few written records had escaped the studio shredder. Within a decade, however, film scholars gained access to several major archives containing a surfeit of documents detailing the bureaucratic operations of the Dream Factory. The Production Code Administration (PCA) Archive is one of the richest of these sources, describing the negotiations between PCA officials and the studios, movie by movie, script draft by script draft. In complete contradiction to the mythology of the Code not functioning during the early 1930s, its records reveal that this period actually saw by far the most interesting negotiations between the studios and the Code administrators over the nature of movie content, as the Code was implemented with increasing efficiency and strictness after 1930. Throughout the period, movie content was changed to conform to the Code's evolving case law.

A number of authoritative books - Lea Jacobs' The Wages of Sin, Tino Balio's Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, Ruth Vasey's The World According to Hollywood – have established quite unequivocally that the old account must be discarded, since it is demonstrably incorrect to suggest that movies made between 1930 and 1934 were “uncensored”. Individual recommendations might be disputed, often in hyperbolic language, but the Code's role in the production process was not a matter of contention, and studio personnel did not resist its implementation. Sklar's account of the Golden Age of Turbulence relied on an analysis of about 25 movies, or approximately one percent of Hollywood's total output of feature pictures between 1930 and 1934. The critical canon of “pre-Code cinema” to be found in the schedules of American Movie Classics, is now perhaps ten times that size.

The early 1930s is, indeed, one of Hollywood's Golden Ages of Turbulence, like the early 1970s and the early 1990s, when a combination of economic conditions and technological developments destabilised the established patterns of audience preference. As the Code's first administrator, Jason Joy, explained, studios had to develop a system of representational conventions “from which conclusions might be drawn by the sophisticated mind, but which would mean nothing to the unsophisticated and inexperienced”. Much of the work of self-regulation lay in the maintenance of this system of conventions, and as such, it operated, however perversely, as an enabling mechanism at the same time that it was a repressive one. The rules of both conduct and representation under these conditions were perhaps most cogently articulated by F. Scott Fitzgerald's Monroe Stahr in The Last Tycoon, explaining to his scriptwriters how the audience is to understand their heroine's motivation: "At all times, at all moments when she is on the screen in our sight, she wants to sleep with Ken Willard… Whatever she does, it is in place of sleeping with Ken Willard. If she walks down the street she is walking to sleep with Ken Willard, if she eats her food it is to give her enough strength to sleep with Ken Willard. But at no time do you give the impression that she would even consider sleeping with Ken Willard unless they were properly sanctified." Source: sensesofcinema.com

December 21, 2014, at 6:00 AM: THE WOMEN (1939) - TCM

A happily married woman lets her catty friends talk her into divorce when her husband strays.

Director: George Cukor Cast: Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, Paulette Goddard, Joan Fontaine, etc.

Writing credits (based on Clare Boothe Luce's play): Anita Loos, Jane Murfin, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Donald Ogden Stewart

Norma Shearer's beauty, hard work, down-to-earth charm and her marriage to Irving Thalberg, the film executive, made her a leading light of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios and a pillar of California film society. Miss Shearer kept some of her down-to-earth style in later years, even after Mr. Thalberg's death of pneumonia in 1937 had made her rich; he left her and their two children $4.5 million. Miss Shearer's popularity proved strong during her 20-year career, with many of the studio's plum roles hers for the taking, and approved by her husband. One example was the Lynn Fontanne role in the 1939 ''Idiot's Delight,'' opposite Clark Gable in the Alfred Lunt part. The movie was adapted from Robert E. Sherwood's antiwar play. She drew good reviews for another Broadway transition, ''The Women,'' and for ''Escape,'' a strong anti-Nazi drama co-starring Robert Taylor. Miss Shearer retired from the screen after making ''Her Cardboard Lover,'' which received poor notices in 1942. Source: www.nytimes.com

Irving Thalberg handed F. Scott Fitzgerald his new assignment: make Jean Harlow a star. Since "Red-Headed Woman" (1932) was an important picture, Eddie Mannix was present. Mannix, a former bouncer at Palisades Amusement Park and now a special aid to L. B. Mayer, was one executive who gave Fitzgerald trouble from the moment he entered MGM in 1931 to the moment he left for good in 1938. Ruling over the assembly, his thin knees drawn up beside him in his chair, was Thalberg himself. Everyone was there, except Jack Conway, the film’s director. “The directors did not appear at these showings,” Fitzgerald would later explain in The Last Tycoon, “officially because their work was considered done, actually because few punches were pulled here as money ran out in silver spools. There had evolved a delicate staying away.”

“Scott Fitzgerald is almost the only writer who never has cause to complain of his Hollywood welcome,” Dorothy Speare observed at the time. “He is famous even in Hollywood, where his meteoric arrivals and departures are discussed in film circles as avidly as they discuss themselves.” He was hired to help write a screen adaptation of Redheaded Woman (1931), a novel by his imitator Katharine Brush. Fitzgerald was faced with the problem of trying to write like a copy of himself, and it showed. As Fitzgerald later explained to his daughter: "Far from approaching it too confidently I was far too humble. I ran afoul of a bastard named [Marcel] de Sano, since a suicide, and let myself be gypped out of command. I wrote the picture and he changed as I wrote. I tried to get at Thalberg but was erroneously warned against it as 'bad taste.' Result—a bad script." Fitzgerald did eventually see Thalberg, but it was at Thalberg’s request; he had just read what Fitzgerald and his collaborator were preparing for Harlow, and he evidently smelled smoke once again. All that remains of the work which Fitzgerald did for Thalberg is an unfinished seventy-six page script, the one de Sano reworked. -"Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood" (1972) by Aaron Latham

Friday, November 21, 2014

"The Great Gatsby" (1949) starring Alan Ladd

F. Scott Fitzgerald's classic story of the "prohibition crowd," which he told with real irony and pity in "The Great Gatsby" back in 1925, has been brought to the screen by Paramount with particular emphasis upon the aspects of the sentimental romance that formed the thread of the novel's fragile plot. Indeed, there are reasons for suspecting that Paramount selected this old tale primarily as a standard conveyance for the image of its charm boy, Alan Ladd. For most of the tragic implications and bitter ironies of Mr. Fitzgerald's work have gone by the board in allowing for the generous exhibition of Mr. Ladd. The period of the Nineteen Twenties is briefly and inadequately sketched with a jumble of gay Long Island parties, old clothes, old songs and old cars. The baneful influence of prohibition and the disillusionment of post-World War I are not in the least integrated into the projection of the man.

A bit of illumination of the brittle and faithless jazz-age type is delivered in irritating snatches by our old friend, Betty Field, playing the married woman whom Gatsby loves in vain. And Barry Sullivan turns in a moderately sturdy account of the lady's Yale-man husband who is rotten at the core. As the pious observer and narrator of all that happens in this film. Macdonald Carey does a fair imitation of a youthful Father Time, and Ruth Hussey is mainly scenery as a wise-cracking golfing champ. Howard da Silva, Shelley Winters and Elisha Cook Jr. have secondary roles which they fill without any distinction or significance to the Fitzgerald tale. Source: www.nytimes.com

"The Great Gatsby" (1949) directed by Elliott Nugent, starring Alan Ladd and Betty Field

A bit of illumination of the brittle and faithless jazz-age type is delivered in irritating snatches by our old friend, Betty Field, playing the married woman whom Gatsby loves in vain. And Barry Sullivan turns in a moderately sturdy account of the lady's Yale-man husband who is rotten at the core. As the pious observer and narrator of all that happens in this film. Macdonald Carey does a fair imitation of a youthful Father Time, and Ruth Hussey is mainly scenery as a wise-cracking golfing champ. Howard da Silva, Shelley Winters and Elisha Cook Jr. have secondary roles which they fill without any distinction or significance to the Fitzgerald tale. Source: www.nytimes.com

"The Great Gatsby" (1949) directed by Elliott Nugent, starring Alan Ladd and Betty Field

F. Scott Fitzgerald, Luxury goods, Tinseltown

F. Scott Fitzgerald was so much the professionally successful American author trying to beat the old masters, was so poisonously bright and yet so fluently and vulnerably self-absorbed, that he flattered every writer of his own generation into feeling old and wise. But he was American youth writing— with a miraculously intact belief in romantic love that made the critics see through the college exhibitionism in This Side of Paradise. They were naturally generous and enthusiastic in a way serious critics of fiction are not today. They recognized that Fitzgerald was better than he allowed himself to be. He was the shining boy, already the Chatterton of our literature, who even at college had known that he wanted to be “one of the greatest writers who have ever lived.” Glenway Wescott was to say at the time of his death, “he had the best narrative gift of the century.” These “writing friends” were his nearest critics, his most loyal —from Wilson and John Peale Bishop at college to Gertrude Stein, Hemingway, Lardner, Dos Passos, and others; how clearly he was their “darling,” their “genius,” just as he was only too soon to become their “fool.” Peter Monro Jack thought Fitzgerald might have been the Proust of his generation, that his misfortunes were due to a lack of constructive and helpful criticism. Of course no writer ever gets enough of this—perhaps not even a Maupassant working directly under Flaubert, or an Eliot revising and cutting The Waste Land under the tutelage of Ezra Pound. Even when Fitzgerald was sick and desperate, he worked his way through the open anxieties of Tender Is the Night to the biting authenticity of The Last Tycoon, some of whose pages have the eerie clarity of a man writing from hell.

He said it all in a letter to his daughter written a few months before his death: “… I wish now I‘d never relaxed or looked back—but said at the end of The Great Gatsby: ‘I‘ve found my line—from now on this comes first. This is my immediate duty— without this I‘m nothing.‘” To be a Proust you have, at the very least, to give up the world and give in to the “tyrant” of your intelligence, even if it threatens to devour you. Far from giving up his world—he was about as metaphysical in his tastes as Franklin D. Roosevelt—he could never make up his mind (until it was made up for him, by the nearness of death) whether he was Jay Gatsby trying to win back the love of his life from the rich, or Dick Diver bestowing his “trick of the heart” on the shallow fashionables along the Riviera, or Monroe Stahr trying to do an honest inside job in Hollywood. And it is to be noticed that richer and subtler as the novels become, the heroes grow progressively more alone, became more aware—Fitzgerald‘s synonym for a state near to death.

That fear of awareness and aloneness is in our culture; Fitzgerald‘s critics could not have helped him there. For as they emphasize here over and again, he wanted two different things equally well—and though his art found its “tensile balance” in this conflict, it certainly exhausted him as a man. There was a headlong fatality about him which, in the long silence between The Great Gatsby and Tender Is the Night, the critics could only watch in amazement, some in derision. Fitzgerald‘s collapse served the critics of the thirties only too well. It was a time when many who sat in judgment over him showed that they actually feared fresh individual writing. Only a few reviewers, notably John Chamberlain and C. Hartley Grattan, publicly recognized the emotional depth and active social intelligence of Tender Is the Night as well as its more obvious neuroticism.

There is ill-concealed exasperation even in some of the more affirmative essays written after The Last Tycoon and The Crack-up. One reason for this is Fitzgerald‘s “romanticism.” This term has always been meaningless when applied to our literary history, but it has a special sting now both in our hardboiled culture (Time, for example, once disposed of Fitzgerald as “the last U.S. Romantic") and in our academic literary culture. Serious criticism of fiction in America today has no sense of assisting a creative movement; it footnotes the old masters. It insists on explanations of the creative achievement in fiction even when there may be none easily forthcoming, and tends to distrust, just a little, a writer who constantly crossed and recrossed the border line between highbrow and popular literature in this country, and who actually wrote some of his best stories for the smooth-paper magazines.

But Fitzgerald is one of those novelists whom it is easier to appreciate than to explain, and whom it is possible, and even fascinating, to read over and over—it has often been remarked that Tender Is the Night grows better on each re-reading—without always being able to account for the sources of your pleasure. American critics return again and again to the fact that in a land of promise, “failure” will always be a classic theme. And that the modern American artist‘s struggle for integrity against the foes in his own household shows its richest meaning in a writer like Fitzgerald, who found those foes in his own heart. These late essays round out an historical cycle—not simply from war to war, or from success to neglect to revival, as it is now the fashion to do, we are so hungry for real writers—but from American to American, from self to self. -"F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Man and his Work" (1951) by Alfred Kazin

A bare 0.004 percent of the world's adult population controls nearly $30 trillion in assets, 13 percent of the world's total wealth, according to a new study released Thursday. And perhaps unsurprisingly, the study by the Swiss bank UBS and luxury industry consultant Wealth-X said the concentration of money in the hands of the ultra-rich is growing. The report said 211,275 million people qualify as "ultra-high net worth" (UHNW) -- those with assets above $30 million. Of them, 2,325 have more than $1 billion.

As F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, the rich are different. The average UHNW-er spends $1 million a year on luxury goods and services. Yet, the study points out, luxury items can be "part and parcel of their lifestyle and are not necessarily considered a 'luxury.'" Source: www.i24news.tv

F. Scott Fitzgerald (Letter to Zelda, April 1938): "You are not married to a rich millionaire of thirty but to a pretty broken and prematurely old man who hasn't a penny except what he can bring out of a weary mind and a sick body. I have heard nothing from you and a word would be reassuring because I am always concerned about you."

The Day of the Locust meets The Devil in the White City and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil in this juicy, untold Hollywood story. By 1920, the movies had suddenly become America’s new favorite pastime, and one of the nation’s largest industries. Yet Hollywood’s glittering ascendency was threatened by a string of headline-grabbing tragedies—including the murder of William Desmond Taylor, the popular president of the Motion Picture Directors Association, a legendary crime that has remained unsolved until now. Along the way, Mann brings to life Los Angeles in the Roaring Twenties: a sparkling yet schizophrenic town filled with party girls, drug dealers, religious zealots, newly-minted legends and starlets already past their prime—a dangerous place where the powerful could still run afoul of the desperate.

In his unfinished novel The Last Tycoon, F. Scott Fitzgerald would write that Hollywood could only be understood “dimly and in flashes.” Fewer than half a dozen people, he said, had “ever been able to keep the whole equation of pictures in their heads.”

Zukor was one of those few. Not until 1948 did the government finally force the movie studios —all of them, not just Paramount— to divest themselves of their theater chains. By then Zukor was happily ensconced as Chairman Emeritus. In 1953 he published a memoir, The Public Is Never Wrong, which he dedicated to his wife Lottie. Of the Taylor case, Zukor said it made for “good reading,” and recalled the fodder it gave to “dozens of special correspondents” who painted Hollywood as “a wicked, wicked city.” Of William Desmond Taylor’s papers, or the actions he’d taken after reading them, Zukor said nothing. He took that secret with him to the grave. On Hollywood Boulevard, the locusts now ruled. Movie premieres had been replaced with drug deals. And across the backlots of the once thrumping movie studios, a terrible silence prevailed. The system Adolph Zukor and Marcus Loew had worked so diligently to create was in its final days. -"Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood" (2014) by William J. Mann

He said it all in a letter to his daughter written a few months before his death: “… I wish now I‘d never relaxed or looked back—but said at the end of The Great Gatsby: ‘I‘ve found my line—from now on this comes first. This is my immediate duty— without this I‘m nothing.‘” To be a Proust you have, at the very least, to give up the world and give in to the “tyrant” of your intelligence, even if it threatens to devour you. Far from giving up his world—he was about as metaphysical in his tastes as Franklin D. Roosevelt—he could never make up his mind (until it was made up for him, by the nearness of death) whether he was Jay Gatsby trying to win back the love of his life from the rich, or Dick Diver bestowing his “trick of the heart” on the shallow fashionables along the Riviera, or Monroe Stahr trying to do an honest inside job in Hollywood. And it is to be noticed that richer and subtler as the novels become, the heroes grow progressively more alone, became more aware—Fitzgerald‘s synonym for a state near to death.

That fear of awareness and aloneness is in our culture; Fitzgerald‘s critics could not have helped him there. For as they emphasize here over and again, he wanted two different things equally well—and though his art found its “tensile balance” in this conflict, it certainly exhausted him as a man. There was a headlong fatality about him which, in the long silence between The Great Gatsby and Tender Is the Night, the critics could only watch in amazement, some in derision. Fitzgerald‘s collapse served the critics of the thirties only too well. It was a time when many who sat in judgment over him showed that they actually feared fresh individual writing. Only a few reviewers, notably John Chamberlain and C. Hartley Grattan, publicly recognized the emotional depth and active social intelligence of Tender Is the Night as well as its more obvious neuroticism.

There is ill-concealed exasperation even in some of the more affirmative essays written after The Last Tycoon and The Crack-up. One reason for this is Fitzgerald‘s “romanticism.” This term has always been meaningless when applied to our literary history, but it has a special sting now both in our hardboiled culture (Time, for example, once disposed of Fitzgerald as “the last U.S. Romantic") and in our academic literary culture. Serious criticism of fiction in America today has no sense of assisting a creative movement; it footnotes the old masters. It insists on explanations of the creative achievement in fiction even when there may be none easily forthcoming, and tends to distrust, just a little, a writer who constantly crossed and recrossed the border line between highbrow and popular literature in this country, and who actually wrote some of his best stories for the smooth-paper magazines.

But Fitzgerald is one of those novelists whom it is easier to appreciate than to explain, and whom it is possible, and even fascinating, to read over and over—it has often been remarked that Tender Is the Night grows better on each re-reading—without always being able to account for the sources of your pleasure. American critics return again and again to the fact that in a land of promise, “failure” will always be a classic theme. And that the modern American artist‘s struggle for integrity against the foes in his own household shows its richest meaning in a writer like Fitzgerald, who found those foes in his own heart. These late essays round out an historical cycle—not simply from war to war, or from success to neglect to revival, as it is now the fashion to do, we are so hungry for real writers—but from American to American, from self to self. -"F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Man and his Work" (1951) by Alfred Kazin

A bare 0.004 percent of the world's adult population controls nearly $30 trillion in assets, 13 percent of the world's total wealth, according to a new study released Thursday. And perhaps unsurprisingly, the study by the Swiss bank UBS and luxury industry consultant Wealth-X said the concentration of money in the hands of the ultra-rich is growing. The report said 211,275 million people qualify as "ultra-high net worth" (UHNW) -- those with assets above $30 million. Of them, 2,325 have more than $1 billion.

As F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, the rich are different. The average UHNW-er spends $1 million a year on luxury goods and services. Yet, the study points out, luxury items can be "part and parcel of their lifestyle and are not necessarily considered a 'luxury.'" Source: www.i24news.tv

F. Scott Fitzgerald (Letter to Zelda, April 1938): "You are not married to a rich millionaire of thirty but to a pretty broken and prematurely old man who hasn't a penny except what he can bring out of a weary mind and a sick body. I have heard nothing from you and a word would be reassuring because I am always concerned about you."

The Day of the Locust meets The Devil in the White City and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil in this juicy, untold Hollywood story. By 1920, the movies had suddenly become America’s new favorite pastime, and one of the nation’s largest industries. Yet Hollywood’s glittering ascendency was threatened by a string of headline-grabbing tragedies—including the murder of William Desmond Taylor, the popular president of the Motion Picture Directors Association, a legendary crime that has remained unsolved until now. Along the way, Mann brings to life Los Angeles in the Roaring Twenties: a sparkling yet schizophrenic town filled with party girls, drug dealers, religious zealots, newly-minted legends and starlets already past their prime—a dangerous place where the powerful could still run afoul of the desperate.

In his unfinished novel The Last Tycoon, F. Scott Fitzgerald would write that Hollywood could only be understood “dimly and in flashes.” Fewer than half a dozen people, he said, had “ever been able to keep the whole equation of pictures in their heads.”

Zukor was one of those few. Not until 1948 did the government finally force the movie studios —all of them, not just Paramount— to divest themselves of their theater chains. By then Zukor was happily ensconced as Chairman Emeritus. In 1953 he published a memoir, The Public Is Never Wrong, which he dedicated to his wife Lottie. Of the Taylor case, Zukor said it made for “good reading,” and recalled the fodder it gave to “dozens of special correspondents” who painted Hollywood as “a wicked, wicked city.” Of William Desmond Taylor’s papers, or the actions he’d taken after reading them, Zukor said nothing. He took that secret with him to the grave. On Hollywood Boulevard, the locusts now ruled. Movie premieres had been replaced with drug deals. And across the backlots of the once thrumping movie studios, a terrible silence prevailed. The system Adolph Zukor and Marcus Loew had worked so diligently to create was in its final days. -"Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood" (2014) by William J. Mann

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

F. Scott Fitzgerald's Fiction and Self-Creation

“It is an escape into a lavish, romantic past that perhaps will not come again into our time.” -F. Scott Fitzgerald on The Last Tycoon

“Fitzgerald’s work has always deeply moved me,” writes John T. Irwin, author of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Fiction: An Almost Theatrical Innocence (2014). Irwin intersperses together biographical details and sharp essays about his literary idol’s most celebrated stories, evoking a young Scott who deserted Princeton and his mature version: the disillusioned screenwriter living in Hollywood two decades later. This is a thoroughly researched study, in a more academic tone as opposed to previous scrutinies Fool For Love (2012) by Scott Donaldson and Fitzgerald’s salacious biography by Jeffrey Meyers (2013).

The book is divided into six highly engaging chapters pointing out several thematic categories: “Compensating Visions in The Great Gatsby,” “Fitzgerald as a Southern Writer,” “The Importance of Repose,” “An Almost Theatrical Innocence,” “Fitzgerald and the Mythical Method,” and “On the Son’s Own Terms.” Throughout these episodes, Irwin emphasizes Fitzgerald’s theatrical performance as writer vs. his real-life character and the conflict originated by his self-creations, resulting in a meritorius analysis of the range of his prose—far more varied and complex than many critics who pigeonholed him as the ephemeral Jazz Age’s chronicler could ever presume.

In Romantic Revisions in Novels from the Americas (2013) Lauren Rule Maxwell had explored the influence of John Keats (Fitzgerald’s favorite poet), highlighting the shirts passage of The Great Gatsby, tracing it back to Keats’s long poem The Eve of St. Agnes (1820). Irwin utilizes the same type of invocation relating to possible influences from popular noir writers as Dashiell Hammett or Raymond Chandler on Fitzgeraldian story-telling techniques.

In 1915, Scott had written in his ledger: “If I couldn’t be perfect, I wouldn’t be anything” -which can be linked to his fragment from The Great Gatsby (now considered the great American novel but unfortunately rejected from the Modern Library in the early 1940s because of low sales): “Jay Gatsby of West Egg sprung from his Platonic conception of himself. He was a son of God — and to this conception he was faithful to the end.” Edmund Wilson, Fitzgerald’s editor and ‘intellectual conscience’, completed the unfinished novel The Last Tycoon (1941) using Fitzgerald’s personal notes and drafts, and reckoned his Princeton friend as “a martyr, a sacrificial victim, a semi-divine personage” after his premature death (aged 44).

Irwin uses Sartre’s notion of ‘the Other’ to interpret Gatsby's journey across two New York suburbs. He finds Gatsby constantly reinventing a persona to be admired by others, remodeling his past in order to fit in the wealthy milieu. Irwin argues that St. Paul’s genius wordsmith also sort of recomposed his own life by adapting it into new social circles, like New York’s 1920s modernity, French Riviera’s bohemia, or Hollywood’s commissary. In all of these disparate environments, Fitzgerald is capable of stripping their deceptive façades; in one of his Catholic stories, Absolution, an amusement park is a symbol of the false world of material obscenity confronted with an imperishable God.

Irwin states in Chapter II: “Scott Fitzgerald understood that in the twentieth century, when America would become the richest and most powerful nation in the world, the struggle between money and breeding, between the arrogance of wealth and the reticence of good instincts, between greed and human values, would become the deepest, most serious theme of the American novel.” The narrator of The Great Gatsby, Nick, muses: “He talked a lot about the past, and I gathered that he wanted to recover something, some idea of himself perhaps, that had gone into loving Daisy.”

Likewise, in So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures (2014), Maureen Corrigan draws parallels between Fitzgerald’s scenarios with frequent allusions to his era’s pop culture tropes. In her chapter “Rhapsody in Noir,” she stretches the notion that “Gatsby” is a herald of the hardboiled pulp fiction, as is reflected in James Gatz/Jay Gatsby’s underworld activities.

J. D. Salinger once said he was drawn to Fitzgerald because of his “intellectual power,” since he was one of the rare visionaries who would anticipate the fall (or death) of the American Dream, the advent of our present rootless U.S.A. “Of course the past can be repeated,” Gatsby assures to Nick Carraway.

The eyes of Dr. T. J. Eckleburg’s advertisement seem to signal the collapse of America’s self-image. “I’m going to fix everything just the way it was before,” Gatsby determines without remotely suspecting his betraying fate. In the essay Fitzgerald’s Brave New World, Edwin Fussell mentions the uniqueness of the American experience exemplified by expressions as “ragged edge of the universe,” or “damp gleam of hope” through The Great Gastby: “After exploring his materials to their limits, Fitzgerald knew that he had discovered a universal pattern of desire and belief and that in it was compounded the imaginative history of modern, especially American, civilization.” Roger Lewis, in his essay Money, Love, and Aspiration in The Great Gatsby (2002) proposes: “The last sentence of the novel, ‘So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past,’ points out that all of our great dreams are grounded in impossibility.”

Fitzgerald’s wife and muse Zelda Sayre had been diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1930, and their relationship hit hard times; however their granddaughter Eleanor Lanahan affirmed: “their marriage was one of the great love stories of all time, the tragedies were there, but love survived.” In 1933, in the Fitzgeralds’ rented Victorian cottage La Paix, under psychiatrist Thomas Rennie’s supervision, Zelda and Scott had a heated argument when he reminded her of the terrible cost of becoming a writer and “endless trying to dig out the essential truth, the essential justice.” In 1938, in a letter to Frances Turnbull, Fitzgerald warned her that as a writer, “you have to sell your heart, your strongest reactions.” In another letter, Fitzgerald would write of Zelda’s illness almost pridefully: “I cherish her most extravagant hallucinations.”

In 1931, Margaret Egloff had felt Ernest Hemingway was being ungrateful to Fitzgerald (who had helped and promoted Hemingway selflessly), but she thought Fitzgerald accepted the “sense of the fight to the death between men for supremacy.” “Shy and deeply introverted… Fitzgerald was a man divided. He was analytical, with a mania for artistic perfection. He had markings of fame and fortune, but also a temperament which doomed him to see himself as a failure. He might be called a natural schizo —an artist at war with himself and the world around him,” opines Tommy Buttita in The Lost Summer: A Personal Memoir of F. Scott Fitzgerald (2003).

Fitzgerald’s duality is exposed in his own remark: “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” In the Chapter 4 (‘An Almost Theatrical Innocence’), “Fitzgerald’s sense of persevering through humiliations and struggles is part of what he pours into the Pat Hobby character, the other part being a wry humor at Hobby’s expense meant to cauterize any hint of self-pity… also served perhaps as a defense mechanism, an imaginative exorcism of any fear that he himself could ever sink that low.”

Caught in a claustophobic Hollywood in his later years (“Isn’t Hollywood a dump… A hideous town, full of the human spirit at a new low of debasement”), Fitzgerald suffered from insomnia, continually craving Coca-Cola and fudge to combat his hypoglycemia. He felt displaced and out of touch, relegated now to a position as freelance screenwriter. Despite his harsh criticism towards the Factory of Dreams, “he wasn’t a film snob, he was fascinated by films. He had a gift for dialogue,” according to Budd Schulberg, with whom he’d collaborated during the Winter Carnival fiasco in 1939.

On the bright side, the Tinseltown atmosphere allowed Fitzgerald to develop crushes on actresses, like Lois Moran (his romantic affair in 1927), Maureen O’Sullivan (who requested him to rewrite her role for A Yank at Oxford) or Loretta Young (whom he described as ‘his type’). During his sleepless nights, Fitzgerald annotated many painful thoughts that would be included in his Crack-Up essay Sleeping and Waking: “I need not have broken myself trying to break what was unbreakable… what if all, after death, was an eternal quivering on the edge of an abyss, with everything base and vicious in oneself urging one forward and the baseness and viciousness of the world just ahead. No choice, no road, no hope — I am a ghost now as the clock strikes four.”

In 1945 Edmund Wilson had edited The Crack-Up (a collection of Fitzgerald’s autobiographical essays originally published in Esquire magazine in 1936), reviewed by Lionel Trilling as a proof of his “heroic awareness”: “The root of Fitzgerald’s heroism is to be found, as it sometimes is in tragic heroes, in his power of love.” In one of his revelations found in The Crack-Up, he confessed to having forgotten “the complicated dark mixture of my youth and infancy that made me a fiction writer instead of a fireman or a soldier," and how he had "buried my first childish love of myself, my belief that I would never die like other people, and that I wasn’t the son of my parents.” Irwin adduces: “Significantly, this description of the death of his childish self-love and his belief that he would never die is immediately preceded by the author’s pointing out another ‘dark corner’ in the cellar.”

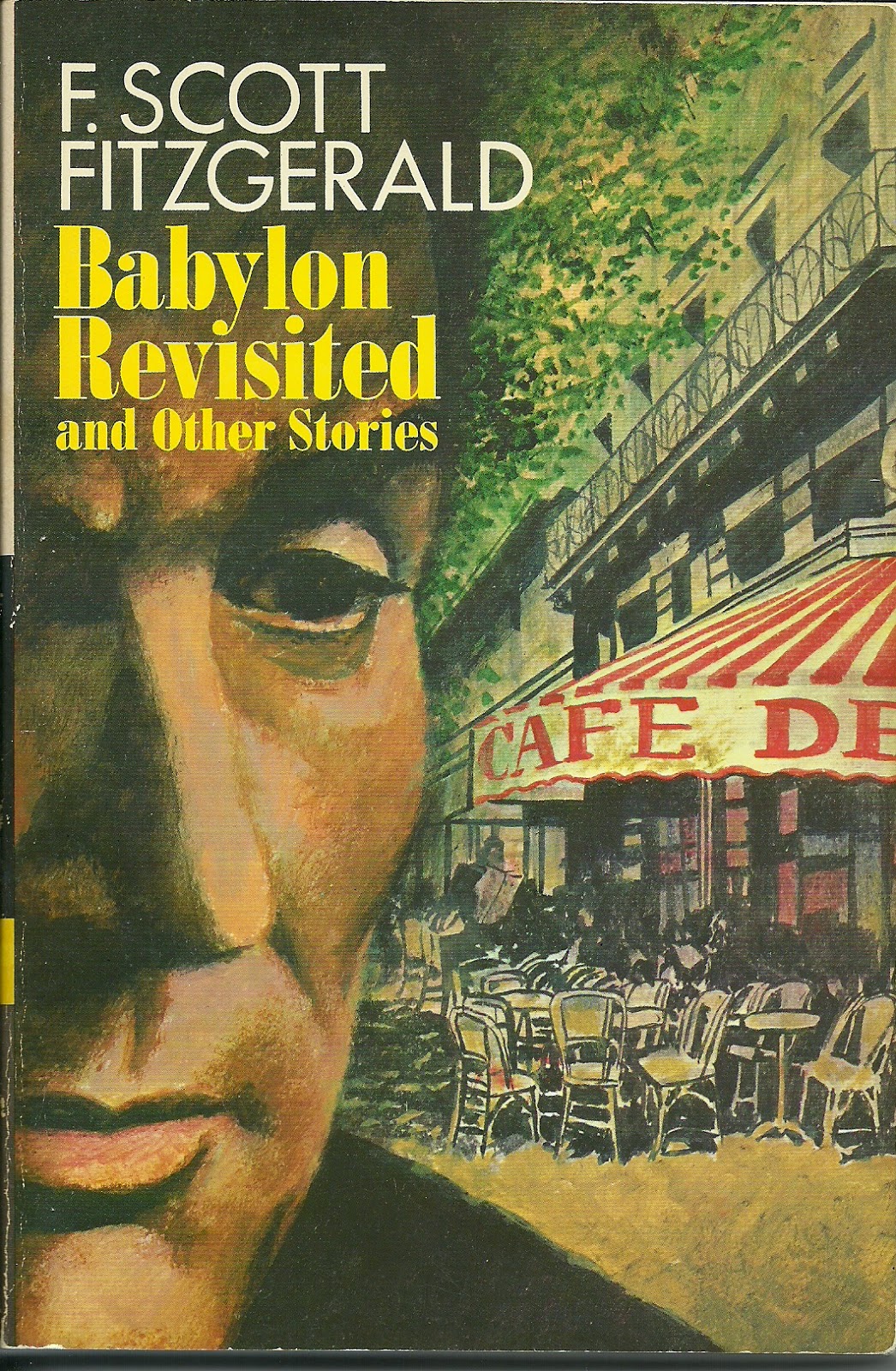

Working with producer Lester Cowan on Babylon Revisited (a short story inspired on the 1929 stock market crash), Fitzgerald saw as a small triumph being able to bring Cowan to tears by enacting one of his sorrowful vignettes on the phone. “At last I’ve made a son-of-a-bitch producer cry,” he consoled himself. Fitzgerald’s screenplay wouldn’t materialize and although he had participated in a handful of film projects (Red-Headed Woman, A Yank at Oxford, Marie Antoinette, Gone With the Wind, The Women, Madame Curie), he received only one screen credit in 1938 for Three Comrades.

Sheilah Graham (a Hollywood gossip columnist) maintained a three-year sentimental relationship with Fitzgerald and helped him focus on his final novel The Last Tycoon. Monroe Stahr (a composite character of Fitzgerald and producer Irving Thalberg) is torn between his duty at the studios and a romance with Kathleen Moore (inspired by Graham), while the corrupt cliqués are revealed to the reader with frankness and melancholic irony.

On 21 December 1940, Fitzgerald collapsed on the floor at Sheilah Graham’s apartment after suffering a fatidic massive heart attack. His nurse and secretary Frances Kroll Ring discovered an envelope put aside containing $700, enough to receive the cheapest funeral at hand (mourned by only thirty attendants, Zelda and Sheilah not among them). “It was devastating,” said Ms Kroll, as she rememorated Scott’s gentlemanly demeanor: “He was a kind man but he converted that kindness into weakness.”

Ernest Hemingway (long-time estranged from his former mentor), referred to Fitzgerald as “the great tragedy of talent in our bloody generation”. Alice Toklas (Gertrude Stein’s muse) called him: “the most sensitive, the most distinguished, the most gifted and intelligent of all his contemporaries. And the most lovable – he is one of those great tragic American figures.”

“I look out at it, and I think it is the most beautiful history in the world. It is the history of all aspiration, not just the American Dream but the human dream. And if I came at the end of it, that too is a place in the line of the pioneers.” -Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald

Article first published as F. Scott Fitzgerald's Fiction and Self-Creation on Blogcritics.

Also republished in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and obtained the stamp of approval of F. Scott Fitzgerald's granddaughter Eleanor Anne Lanaham (author of "Scottie: The Life of Frances Scott Fitzgerald Lanahan Smith" and co-author of "Zelda: An Illustrated Life: The Private World of Zelda Fitzgerald") with her encouraging and kind words: "What an extraordinary blog! Shows the complexity, talent and charm of F. Scott" Thank you very much, Eleanor, a true honor for me to be appreciated by my article on one of the greatest writers, F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Friday, November 14, 2014

Louise Brooks' Anniversary, Flappers & Philosophers (F. Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald)

Happy Anniversary, Louise Brooks!

Louise Brooks — The stunning tastemaker of the ’20s & ’30s, who made women everywhere chop their hair, and created the bold and wildly popular “flapper girl” movement. Louise Brooks’ dark and exotic looks drew a throng of faithful followers that continues to this day. Early on her onscreen talent was often criticized for being somewhat lackluster– but all that changed with a trip to Berlin. Director G.W. Pabst cast her in two films– Pandora’s Box (1928), and Diary of a lost Girl (1929), that not only cast all doubts about her talent, it also rose her following to cult status. Source: selvedgeyard.com

The flapper era was the time of the worship of youth. Flappers were women of the Jazz Age. Flappers had short hair worn no longer than chin length, called bobs. Their hair was often dyed and waved into flat, head-hugging curls and accessorized with wide, soft headbands. It was a new and most original style for women. A lot of make-up was worn by flappers that they even put on in public which was once unheard of and considered something done only by actresses and whores. Flappers wore short, straight dresses often covered with beads and fringes, usually without pantyhose. Young flappers were known to be very rebellious against their parents, and society blamed their waywardness partially on the media, movies, and film stars like Louise Brooks.

Louise Brooks was a big part of the Jazz Age and had a lot of influence on the women of the 1920 s. Being a film star with a great, original personality she is known for being one of the most extraordinary women to set forth the Flapper era. Her sleek and smooth looks with her signature bob helped define the flapper look. On November 14, 1906, in Cherryvale, Kansas, Mary Louise Brooks was born. In 1910, Brooks performed in her first stage role as Tom Thumb s bride in a Cherryvale church benefit. Over the next few years she danced at men s and women s clubs, fairs, and various other gatherings in southeastern Kansas. At ten years old she was already a serious dancer and very much interested in it. In 1920, Brook s family moved to Wichita, Kansas, and at 13 years old she began studying dance.

Louise Brooks had a typical education and family life. She was very interested in reading and the arts, so in 1922 she traveled to New York City and joined the Denishawn Dance Company. This was the leading modern dance company in America at the time. In 1923, Brooks toured the United States and Canada with Denishawn by train and played a different town nearly every night, but one year later she leaves Denishawn and moves back to New York City. Not too long after her return, she gets a job as a chorus girl in the George White Scandals. Following this she and a good friend of hers sailed to Europe. At 17 years old she gained employment at a leading London nightclub. She became famous in Europe as the first person to dance the Charleston in London, and her performances were great successes.

In 1925, Louise Brooks returned to New York and joins Ziegfeld Follier, and performed in the Ziegfeld production, Louie the 14th. That summer she had an affair with Charlie Chaplin. At the same time, Brooks also appeared in her first film, The Streets of Forgotten Men, and signed a five year contract with Paramount. This same year, she had her first appearance on a magazine cover.

In 1926, she featured as a flapper in A Social Celebrity which launched her film career and introduced the flapper era. Brooks considered F. Scott Fitzgerald had created the flapper figure, and she actually existed in "Scott Fitzgerald's mind and the antics he planted in his mad wife Zelda's mind." -“Flapper Culture and Style: Louise Brooks and the Jazz Age” (The Louise Brooks Society)

"Thrilling scandals by an anxious uncle," yawned Ardita. "Have it filmed. Wicked clubman making eyes at virtuous flapper. Virtuous flapper conclusively vamped by his lurid past. Plans to meet him at Palm Beach. Foiled by anxious uncle." "Will you tell me why the devil you want to marry him?" "I'm sure I couldn't say," said Audits shortly. "Maybe because he's the only man I know, good or bad, who has an imagination and the courage of his convictions. Maybe it's to get away from the young fools that spend their vacuous hours pursuing me around the country. But as for the famous Russian bracelet, you can set your mind at rest on that score. He's going to give it to me at Palm Beach... if you'll show a little intelligence." She put her chin in the air like the statue of France Aroused, and then spoiled the pose somewhat by raising the lemon for action. "Lucky girl," he sighed "I've always wanted to be rich and buy all this beauty." Ardita yawned. "I'd rather be you," she said frankly. "You would... for about a day. But you do seem to possess a lot of nerve for a flapper." -"Flappers and Philosophers" (1920) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

To their own surprise and delight, Scott and Zelda discovered that they were being heralded as models in the cult of youth. Scott was asked to lecture before audiences that were ready to adore him as their spokesman. A literary gossip column reported, “We watched him wave his cigarette at an audience one night not long ago, and capture them by nervous young ramblings, until he had the room (mostly ‘flappers’) swaying with delight. This admiration embarrassed him much —but after we had escaped into the outer darkness he acknowledged, with a grin, that he rather liked it.” Still he and Zelda were safe, Scott thought, “apart from all that,” and if the city bewitched them by offering fresh roles for them, they played them because “We felt like small children in a great bright unexplored barn.”

Zelda was asked by McCall’s magazine for a 2,500-word article on the modern flapper, and they offered her ten cents a word. In June the Metropolitan Magazine did publish her “Eulogy on the Flapper.” Above the article was a sketch of Zelda done by Gordon Bryant. Zelda wrote that the flapper was dead and that she grieved the passing of so original a model, for she saw in the flapper a code for living well: 'Perceiving these things, the Flapper awoke from her lethargy of sub-debism, bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure, she covered her face with powder and paint because she didn’t need it and she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring. She was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do. Mothers disapproved of their sons taking the Flapper to dances, to teas, to swim and most of all to heart. She had mostly masculine friends, but youth does not need friends—it needs only crowds.' -"Zelda: A Biography" (2011) by Nancy Milford

Louise Brooks — The stunning tastemaker of the ’20s & ’30s, who made women everywhere chop their hair, and created the bold and wildly popular “flapper girl” movement. Louise Brooks’ dark and exotic looks drew a throng of faithful followers that continues to this day. Early on her onscreen talent was often criticized for being somewhat lackluster– but all that changed with a trip to Berlin. Director G.W. Pabst cast her in two films– Pandora’s Box (1928), and Diary of a lost Girl (1929), that not only cast all doubts about her talent, it also rose her following to cult status. Source: selvedgeyard.com

The flapper era was the time of the worship of youth. Flappers were women of the Jazz Age. Flappers had short hair worn no longer than chin length, called bobs. Their hair was often dyed and waved into flat, head-hugging curls and accessorized with wide, soft headbands. It was a new and most original style for women. A lot of make-up was worn by flappers that they even put on in public which was once unheard of and considered something done only by actresses and whores. Flappers wore short, straight dresses often covered with beads and fringes, usually without pantyhose. Young flappers were known to be very rebellious against their parents, and society blamed their waywardness partially on the media, movies, and film stars like Louise Brooks.

Louise Brooks was a big part of the Jazz Age and had a lot of influence on the women of the 1920 s. Being a film star with a great, original personality she is known for being one of the most extraordinary women to set forth the Flapper era. Her sleek and smooth looks with her signature bob helped define the flapper look. On November 14, 1906, in Cherryvale, Kansas, Mary Louise Brooks was born. In 1910, Brooks performed in her first stage role as Tom Thumb s bride in a Cherryvale church benefit. Over the next few years she danced at men s and women s clubs, fairs, and various other gatherings in southeastern Kansas. At ten years old she was already a serious dancer and very much interested in it. In 1920, Brook s family moved to Wichita, Kansas, and at 13 years old she began studying dance.

Louise Brooks had a typical education and family life. She was very interested in reading and the arts, so in 1922 she traveled to New York City and joined the Denishawn Dance Company. This was the leading modern dance company in America at the time. In 1923, Brooks toured the United States and Canada with Denishawn by train and played a different town nearly every night, but one year later she leaves Denishawn and moves back to New York City. Not too long after her return, she gets a job as a chorus girl in the George White Scandals. Following this she and a good friend of hers sailed to Europe. At 17 years old she gained employment at a leading London nightclub. She became famous in Europe as the first person to dance the Charleston in London, and her performances were great successes.

In 1925, Louise Brooks returned to New York and joins Ziegfeld Follier, and performed in the Ziegfeld production, Louie the 14th. That summer she had an affair with Charlie Chaplin. At the same time, Brooks also appeared in her first film, The Streets of Forgotten Men, and signed a five year contract with Paramount. This same year, she had her first appearance on a magazine cover.

In 1926, she featured as a flapper in A Social Celebrity which launched her film career and introduced the flapper era. Brooks considered F. Scott Fitzgerald had created the flapper figure, and she actually existed in "Scott Fitzgerald's mind and the antics he planted in his mad wife Zelda's mind." -“Flapper Culture and Style: Louise Brooks and the Jazz Age” (The Louise Brooks Society)

"Thrilling scandals by an anxious uncle," yawned Ardita. "Have it filmed. Wicked clubman making eyes at virtuous flapper. Virtuous flapper conclusively vamped by his lurid past. Plans to meet him at Palm Beach. Foiled by anxious uncle." "Will you tell me why the devil you want to marry him?" "I'm sure I couldn't say," said Audits shortly. "Maybe because he's the only man I know, good or bad, who has an imagination and the courage of his convictions. Maybe it's to get away from the young fools that spend their vacuous hours pursuing me around the country. But as for the famous Russian bracelet, you can set your mind at rest on that score. He's going to give it to me at Palm Beach... if you'll show a little intelligence." She put her chin in the air like the statue of France Aroused, and then spoiled the pose somewhat by raising the lemon for action. "Lucky girl," he sighed "I've always wanted to be rich and buy all this beauty." Ardita yawned. "I'd rather be you," she said frankly. "You would... for about a day. But you do seem to possess a lot of nerve for a flapper." -"Flappers and Philosophers" (1920) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

To their own surprise and delight, Scott and Zelda discovered that they were being heralded as models in the cult of youth. Scott was asked to lecture before audiences that were ready to adore him as their spokesman. A literary gossip column reported, “We watched him wave his cigarette at an audience one night not long ago, and capture them by nervous young ramblings, until he had the room (mostly ‘flappers’) swaying with delight. This admiration embarrassed him much —but after we had escaped into the outer darkness he acknowledged, with a grin, that he rather liked it.” Still he and Zelda were safe, Scott thought, “apart from all that,” and if the city bewitched them by offering fresh roles for them, they played them because “We felt like small children in a great bright unexplored barn.”

Zelda was asked by McCall’s magazine for a 2,500-word article on the modern flapper, and they offered her ten cents a word. In June the Metropolitan Magazine did publish her “Eulogy on the Flapper.” Above the article was a sketch of Zelda done by Gordon Bryant. Zelda wrote that the flapper was dead and that she grieved the passing of so original a model, for she saw in the flapper a code for living well: 'Perceiving these things, the Flapper awoke from her lethargy of sub-debism, bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure, she covered her face with powder and paint because she didn’t need it and she refused to be bored chiefly because she wasn’t boring. She was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do. Mothers disapproved of their sons taking the Flapper to dances, to teas, to swim and most of all to heart. She had mostly masculine friends, but youth does not need friends—it needs only crowds.' -"Zelda: A Biography" (2011) by Nancy Milford

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

.jpg)

_01.jpg)