Monday, November 10, 2014

Mabel Normand's Anniversary, F. Scott Fitzgerald's Hollywood Almanac

TILLIE'S PUNCTURED ROMANCE

Mack Sennett Productions 6000 ft., released Nov. 14, 1914 (Dressler No. 1) dir. Mack Sennett cast: Marie Dressler (Tillie Banks), Charlie Chaplin (Charlie, a City Slicker), Mabel Normand (Mabel, his girl friend), Mack Swain (John Banks, Tillie's Father), Charles Bennett (Douglas Banks, Tillie's Uncle), Charles Murray (Detective), Charley Chase (Detective), Edgar Kennedy (Restaurant Proprietor), Harry McCoy (Pianist), Minta Durfee (Maid), Phyllis Allen (Wardress), Alice Davenport (Guest), Slim Summerville (Policeman), Al St. John (Policeman), Wallace MacDonald (Policeman), Joe Bordeaux (Policeman), G. G. Ligon (Policeman), Gordon Griffith (Newsboy), Billie Bennett (Girl), Rev. D. Simpson (Himself), William Hauber (Policeman) Location: Keystone studio, Los Angeles, CA finished: 7/25/1914

Happy Anniversary, Mabel Normand!

Mabel Normand (1892-1930) was the brief queen of the silent era. Her first picture, Over the Garden Wall, was filmed in 1910 for Vitagraph. From there she joined Keystone Studios, and played a large part in their success. She worked with Charlie Chaplin and Fatty Arbuckle.

Unique for the time, she wrote, directed and starred in several films. Her most memorable being “Mickey” (1918). In 1918 she moved to Goldwyn Studios, where her taste for alcohol and cocaine started taking its toll. She was released from her contract with Goldwyn and went back to Keystone Studios. The 1920s were fraught with scandal – she was associated with two murders. The first, William Desmond Taylor in 1922, and Courtland Dines in 1924. After a long bout with tuberculosis, she died in 1930.

Mabel Normand was once asked by a reporter about her hobbies, to which she replied, “I don’t know. Say anything you like, but don’t say I love to work. That sounds like Mary Pickford, that prissy bitch. Just say I like to pinch babies and twist their legs. And get drunk.”

Pat Hobby’s apartment lay athwart a delicatessen shop on Wilshire Boulevard. And there lay Pat himself, surrounded by his books—the Motion Picture Almanac of 1928 and Barton’s Track Guide, 1939—by his pictures, authentically signed photographs of Mabel Normand and Barbara LaMarr (who, being deceased, had no value in the pawn-shops)—and by his dogs in their cracked leather oxfords, perched on the arm of a slanting settee.

Pat was at “the end of his resources”—though this term is too ominous to describe a fairly usual condition in his life. He was an old-timer in pictures; he had once known sumptuous living, but for the past ten years jobs had been hard to hold—harder to hold than glasses. “Think of it,” he often mourned. “Only a writer—at forty-nine.” All this afternoon he had turned the pages of The Times and The Examiner for an idea. Though he did not intend to compose a motion picture from this idea, he needed it to get him inside a studio. If you had nothing to submit it was increasingly difficult to pass the gate. But though these two newspapers, together with Life, were the sources most commonly combed for “originals,” they yielded him nothing this afternoon. There were wars, a fire in Topanga Canyon, press releases from the studios, municipal corruptions, and always the redeeming deeds of “The Trojuns,” but Pat found nothing that competed in human interest with the betting page. -"No Harm Trying" from "The Pat Hobby Stories" (1940) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

During Fitzgerald’s second year in Hollywood his hopeful ambition turned to discontent. For someone who came there as he had, out of need, there was depression in the flat, drugstore sprawl of Los Angeles with its unnatural glaring sun. Around the studio the older writers treated him with respect, though some of the brash younger ones, who had mastered a technique comparable to making Panama hats under water, made him feel his unimportance. Hollywood was such an industrial town that not to be a power in the movies was to be unknown. “I thought it would be so easy, but it’s been a disappointment. It’s so barren out here. I don’t feel anything out here,” said Fitzgerald.

After working several weeks on A Yank at Oxford, he had been switched to a Remarque war novel, Three Comrades. He liked the material but disliked the interminable story conferences where, as he once said, “personality was worn down to the inevitable low gear of collaboration.” His co-writer, Ted Paramore, was another frustration. According to Fitzgerald Paramore was still turning out “Owen Wister dialogue”—putting such expressions as “Consarn it!” in the mouth of a German sergeant.

The future looked even brighter when Metro took up his option for a year’s renewal of contract at $1250 a week, but in January producer Joe Manckiewicz rewrote the script of Three Comrades so that very few of Fitzgerald’s words remained. Though Manckiewicz liked the way Fitzgerald had brought the characters to life against their background, he found Fitzgerald’s dialogue too flowery—the work of a novelist rather than a scenarist. Fitzgerald’s touches of magic also seemed irrelevant. For example, when one of the three comrades phoned his sweetheart, an angel was supposed to plug in the connection at the hotel switchboard. “How do you film that?” someone asked drily.

Fitzgerald was crushed by what he considered the mutilation of an honest and delicate script, for it wasn’t his nature to write tongue in cheek. “37 pages mine,” he scrawled on Manckiewicz’ version, “about 1/3, but all shadows and rhythm removed.” “To say I’m disillusioned,” he wrote Manckiewicz, “is putting it mildly. For nineteen years I’ve written best selling entertainment, and my dialogue is supposedly right up at the top…. You had something and you have arbitrarily and carelessly torn it to pieces. … I am utterly miserable at seeing months of work and thought negated in one hasty week. I hope you’re big enough to take this letter as it’s meant—a desperate plea to put back the flower cart, the piano-moving, the balcony, the manicure girl—all those touches that were both natural and new. I thought you were going to play fair.” -"Scott Fitzgerald" (2001) by Andrew Turnbull

Friday, November 07, 2014

Orson Welles's final film, Hemingway & Fitzgerald

Great news for movie lovers generally and Orson Welles fans in particular: The director’s storied but unfinished final film, The Other Side of the Wind, may finally be completed and shown next year. As the New York Times reports, the production company Royal Road Entertainment has managed to strike a deal to buy the rights to the movie, with the aim of screening it in California by May 6, 2015, which would have been Welles’ 100th birthday.

According to the Times, the script has its origins in “a tense encounter in 1937 between Ernest Hemingway and a young Welles.” Welles said that a “whiskey-drinking Hemingway” mocked him as one of the “effeminate boys of the theater,” and, when he “mocked him back, Hemingway threw a chair and they scuffled—settling it with a toast that led to an on-again, off-again friendship.” Hemingway apparently “serves as the primary model for Huston’s character.” Source: www.slate.com

A historic hospital where Zelda Fitzgerald, wife of author F. Scott Fitzgerald, died in a fire is for sale. Several historic buildings on the site of the famous Highland Hospital in the northern Montford neighborhood are currently on the market, said Debbie Lane, a realtor with NAI Beverly-Hanks. They include one of the first buildings constructed in Montford and structures used as Highland Hospital, established by Dr. Robert S. Carroll, a distinguished psychiatrist who treated addictions as well as nervous and mental disorders. Carroll moved the hospital from downtown to the Montford location in 1909. In 1948 a fire broke out in the main building, killing nine women including Zelda Fitzgerald, according to the National Park Service, which lists the hospital site as on the National Register of Historic Places. Source: www.citizen-times.com

Zelda had hawk's eyes and a thin mouth and deep-south manners and accent. Watching her face you could see her mind leave the table and go to the night's party and return with her eyes blank as a cat's and then pleased, and the pleasure would show along the thin line of her lips and then be gone. Zelda was jealous of Scott's work and as we got to know them, this fell into a regular pattern. Scott would resolve not to go on all-night drinking parties and to get some exercise each day and work regularly. He would start to work and as soon as he was working well Zelda would begin complaining about how bored she was and get him off on another drunken party. Scott was very much in love with Zelda and he was very jealous of her. He told me many times on our walks of how she had fallen in love with the French navy pilot. But she had never made him really jealous with another man since. This spring she was making him jealous with other women and on the Montmartre parties he was afraid to pass out. This continued for years but, for years too, I had no more loyal friend than Scott when he was sober.

Scott was a man then who looked like a boy with a face between handsome and pretty. He had very fair wavy hair, a high forehead, excited and friendly eyes and a delicate long-lipped Irish mouth. His chin was well built and he had good ears and a handsome, almost beautiful, unmarked nose. This should not have added up to a pretty face, but that came from the colouring, the very fair hair and the mouth. His talent was as natural as the pattern that was made by the dust on a butterfly's wings. At one time he understood it no more than the butterfly did and he did not know when it was brushed or marred. Later he became conscious of his damaged wings and of their construction and he learned to think and could not fly any more because the love of flight was gone and he could only remember when it had been effortless. -"A Moveable Feast" (1964) by Ernest Hemingway

According to the Times, the script has its origins in “a tense encounter in 1937 between Ernest Hemingway and a young Welles.” Welles said that a “whiskey-drinking Hemingway” mocked him as one of the “effeminate boys of the theater,” and, when he “mocked him back, Hemingway threw a chair and they scuffled—settling it with a toast that led to an on-again, off-again friendship.” Hemingway apparently “serves as the primary model for Huston’s character.” Source: www.slate.com

A historic hospital where Zelda Fitzgerald, wife of author F. Scott Fitzgerald, died in a fire is for sale. Several historic buildings on the site of the famous Highland Hospital in the northern Montford neighborhood are currently on the market, said Debbie Lane, a realtor with NAI Beverly-Hanks. They include one of the first buildings constructed in Montford and structures used as Highland Hospital, established by Dr. Robert S. Carroll, a distinguished psychiatrist who treated addictions as well as nervous and mental disorders. Carroll moved the hospital from downtown to the Montford location in 1909. In 1948 a fire broke out in the main building, killing nine women including Zelda Fitzgerald, according to the National Park Service, which lists the hospital site as on the National Register of Historic Places. Source: www.citizen-times.com

Zelda had hawk's eyes and a thin mouth and deep-south manners and accent. Watching her face you could see her mind leave the table and go to the night's party and return with her eyes blank as a cat's and then pleased, and the pleasure would show along the thin line of her lips and then be gone. Zelda was jealous of Scott's work and as we got to know them, this fell into a regular pattern. Scott would resolve not to go on all-night drinking parties and to get some exercise each day and work regularly. He would start to work and as soon as he was working well Zelda would begin complaining about how bored she was and get him off on another drunken party. Scott was very much in love with Zelda and he was very jealous of her. He told me many times on our walks of how she had fallen in love with the French navy pilot. But she had never made him really jealous with another man since. This spring she was making him jealous with other women and on the Montmartre parties he was afraid to pass out. This continued for years but, for years too, I had no more loyal friend than Scott when he was sober.

Scott was a man then who looked like a boy with a face between handsome and pretty. He had very fair wavy hair, a high forehead, excited and friendly eyes and a delicate long-lipped Irish mouth. His chin was well built and he had good ears and a handsome, almost beautiful, unmarked nose. This should not have added up to a pretty face, but that came from the colouring, the very fair hair and the mouth. His talent was as natural as the pattern that was made by the dust on a butterfly's wings. At one time he understood it no more than the butterfly did and he did not know when it was brushed or marred. Later he became conscious of his damaged wings and of their construction and he learned to think and could not fly any more because the love of flight was gone and he could only remember when it had been effortless. -"A Moveable Feast" (1964) by Ernest Hemingway

Monday, November 03, 2014

"Nothing Sacred" (Fredric March), F. Scott Fitzgerald's "The Women"

Carole Lombard and Fredric March in "Nothing Sacred" (1937) directed by William A. Wellman

Hazel Flagg (Carole Lombard) of Warsaw, Vermont, receives the news that her terminal case of radium poisoning from a workplace incident was a complete misdiagnosis with mixed emotions. She is happy not to be dying, but she, who has never traveled the world, was going to use the money paid to her by her factory to go to New York in style. She believes her dreams can still be realized when Wally Cook (Fredric March) arrives in town. He is a New York reporter with the Morning Star newspaper. He believes that Hazel's valiant struggle concerning her impending death is just the type of story he needs to resurrect his name within reporting circles after a recent story he wrote led to scandal and a major demotion at the newspaper. He proposes to take Hazel to New York both to report on her story but also to provide her with a grand farewell to life. She accepts. Wally's story results in Hazel becoming the toast of New York. In spending time together, Wally and Hazel fall in love.

The physical altercations between March and Lombard where they push, kick, and slug one another brought out the ire of the ever vigilante Breen Office, which thought that it was excessively violent. Breen was especially aghast by a man socking and kicking a woman — even if it was for comedic effect. Breen also had the usual complaints about excessive drinking and sexual innuendo. In the midst of shooting Nothing Sacred, the Marches held a dinner party and special screening of the documentary The Spanish Earth written and produced by Ernest Hemingway.

The documentary was in support of the loyalist cause in the Spanish Civil War — strongly anti-fascist and Anti-General Francisco Franco. Hemingway came to Hollywood to give the documentary exposure and to raise money for the loyalist cause. The special screening at the Marches home was just one of several events, and the dinner/ screening guests included John Ford, Joan Crawford, Franchot Tone, Myrna Loy, Samuel Goldwyn, and the writers Lillian Hellman and F. Scott Fitzgerald. -"Fredric March: A Consummate Actor" (2013) by Charles Tranberg

Ernest Hemingway, who, Fitzgerald had written, “talked with the authority of success,” had come to Scott, who “talked with the authority of failure,” for a place to stay and some spending money. Fitzgerald had written that he and Ernest could “never sit across the same table again”; he said that they had “walked over one another with cleats.” In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” Hemingway had written that the very rich had ruined Scott Fitzgerald, and since then he had more than once hinted that movie money had taken up the job where the Eastern rich had left off. But now Ernest, who said that he was waiting for a check from one of the national magazines, needed some of that Hollywood wealth. Scott gave him twenty-five dollars a week allowance.

Fredric March and Joan Crawford in "Susan and God" (1940) directed by George Cukor

Being assigned to The Women was a double disappointment for Fitzgerald. Not only had Infidelity been stopped, but he had been transferred onto, then off of, a story which promised to become a classic film memorial to Irving Thalberg. In a sense the picture Marie Antoinette was Thalberg’s own The Last Tycoon— it was to have been his masterpiece, but his death left it unfinished. Fitzgerald wrote another note to Stromberg: 'Let us change Mary from a passive, simple, easily influenced character, to the exact opposite—an active, intelligent, and courageous character, and see what effect this would have upon the plot of The Women.' To echo the author, a new kind of heroine, in some ways more like Sheilah Graham, who took care of Scott, than the Zelda who required so much care herself. But this new Mary did not intrigue Stromberg or the front office. Fitzgerald was back to the old, familiar heroine he began with. Fitzgerald’s adaptation of The Women is more a step backwards in the direction of the talkative Three Comrades than a step forward into the quiet world of Infidelity. But most of all, Fitzgerald’s screenplay was a step into the classic Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer mold.

To be sure that Fitzgerald understood what type of script was expected of him, Stromberg sent him off to one of the studio projection rooms to see Metro’s Grand Hotel. Ever since the early thirties when Thalberg produced the movie, an all-star extravaganza which paraded many of the company’s most dazzling beauties, including Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford, Metro had been known as “the Grand Hotel of the studios.” Besides the mystical Garbo and the voracious Crawford, this distinctly feminine studio also boarded Jean Harlow, the goddess-whore; Myrna Loy, the unlikely wife; Joan Fontaine, the governess who married well; coy Paulette Goddard; musical Jeanette MacDonald; tragic Luise Rainer; and Rosalind Russell, the heavyweight bust.

Once again one of Fitzgerald’s pictures had gotten good notices, but he failed to share in the glory. By the time the movie was released, he was looking for another job. While The Women was making money all across the country, Fitzgerald wrote his agent Leland Hayward that it would be futile to ask Stromberg for employment. “I reached a dead end on The Women,” he said. -"Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood" (1972) by Aaron Latham

Fredric March in "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" (1931) directed by Rouben Mamoulian

If ever there was a Jekyll and Hyde character, it was F. Scott Fitzgerald, a man of two completely different personalities. One Scott was kind; the other cruel. One was completely mature; the other never grew up. One wanted to be loved and admired; the other wanted to be despised. One tried to make people better than they were; the other tore them down. One was careful to the point of hypochondria; the other reckless of his health and safety. There was Scott the considerate husband and Scott his wife's oppressor; the proud father and the father who embarrassed his daughter. The Scott Fitzgerald I knew best was the mature man, although Jekyll sometimes turned into Hyde. It was, of course, his drinking which brought on the transformation, when even his usually wan and self-contained expression changed into flushed anger. “Which is the real you?” I once asked him. And he replied, “The sober man.” -"The Real F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thirty-Five Years Later" (1976) by Sheilah Graham

Hazel Flagg (Carole Lombard) of Warsaw, Vermont, receives the news that her terminal case of radium poisoning from a workplace incident was a complete misdiagnosis with mixed emotions. She is happy not to be dying, but she, who has never traveled the world, was going to use the money paid to her by her factory to go to New York in style. She believes her dreams can still be realized when Wally Cook (Fredric March) arrives in town. He is a New York reporter with the Morning Star newspaper. He believes that Hazel's valiant struggle concerning her impending death is just the type of story he needs to resurrect his name within reporting circles after a recent story he wrote led to scandal and a major demotion at the newspaper. He proposes to take Hazel to New York both to report on her story but also to provide her with a grand farewell to life. She accepts. Wally's story results in Hazel becoming the toast of New York. In spending time together, Wally and Hazel fall in love.

The physical altercations between March and Lombard where they push, kick, and slug one another brought out the ire of the ever vigilante Breen Office, which thought that it was excessively violent. Breen was especially aghast by a man socking and kicking a woman — even if it was for comedic effect. Breen also had the usual complaints about excessive drinking and sexual innuendo. In the midst of shooting Nothing Sacred, the Marches held a dinner party and special screening of the documentary The Spanish Earth written and produced by Ernest Hemingway.

The documentary was in support of the loyalist cause in the Spanish Civil War — strongly anti-fascist and Anti-General Francisco Franco. Hemingway came to Hollywood to give the documentary exposure and to raise money for the loyalist cause. The special screening at the Marches home was just one of several events, and the dinner/ screening guests included John Ford, Joan Crawford, Franchot Tone, Myrna Loy, Samuel Goldwyn, and the writers Lillian Hellman and F. Scott Fitzgerald. -"Fredric March: A Consummate Actor" (2013) by Charles Tranberg

Ernest Hemingway, who, Fitzgerald had written, “talked with the authority of success,” had come to Scott, who “talked with the authority of failure,” for a place to stay and some spending money. Fitzgerald had written that he and Ernest could “never sit across the same table again”; he said that they had “walked over one another with cleats.” In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” Hemingway had written that the very rich had ruined Scott Fitzgerald, and since then he had more than once hinted that movie money had taken up the job where the Eastern rich had left off. But now Ernest, who said that he was waiting for a check from one of the national magazines, needed some of that Hollywood wealth. Scott gave him twenty-five dollars a week allowance.

Fredric March and Joan Crawford in "Susan and God" (1940) directed by George Cukor

Being assigned to The Women was a double disappointment for Fitzgerald. Not only had Infidelity been stopped, but he had been transferred onto, then off of, a story which promised to become a classic film memorial to Irving Thalberg. In a sense the picture Marie Antoinette was Thalberg’s own The Last Tycoon— it was to have been his masterpiece, but his death left it unfinished. Fitzgerald wrote another note to Stromberg: 'Let us change Mary from a passive, simple, easily influenced character, to the exact opposite—an active, intelligent, and courageous character, and see what effect this would have upon the plot of The Women.' To echo the author, a new kind of heroine, in some ways more like Sheilah Graham, who took care of Scott, than the Zelda who required so much care herself. But this new Mary did not intrigue Stromberg or the front office. Fitzgerald was back to the old, familiar heroine he began with. Fitzgerald’s adaptation of The Women is more a step backwards in the direction of the talkative Three Comrades than a step forward into the quiet world of Infidelity. But most of all, Fitzgerald’s screenplay was a step into the classic Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer mold.

To be sure that Fitzgerald understood what type of script was expected of him, Stromberg sent him off to one of the studio projection rooms to see Metro’s Grand Hotel. Ever since the early thirties when Thalberg produced the movie, an all-star extravaganza which paraded many of the company’s most dazzling beauties, including Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford, Metro had been known as “the Grand Hotel of the studios.” Besides the mystical Garbo and the voracious Crawford, this distinctly feminine studio also boarded Jean Harlow, the goddess-whore; Myrna Loy, the unlikely wife; Joan Fontaine, the governess who married well; coy Paulette Goddard; musical Jeanette MacDonald; tragic Luise Rainer; and Rosalind Russell, the heavyweight bust.

Once again one of Fitzgerald’s pictures had gotten good notices, but he failed to share in the glory. By the time the movie was released, he was looking for another job. While The Women was making money all across the country, Fitzgerald wrote his agent Leland Hayward that it would be futile to ask Stromberg for employment. “I reached a dead end on The Women,” he said. -"Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood" (1972) by Aaron Latham

Fredric March in "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" (1931) directed by Rouben Mamoulian

If ever there was a Jekyll and Hyde character, it was F. Scott Fitzgerald, a man of two completely different personalities. One Scott was kind; the other cruel. One was completely mature; the other never grew up. One wanted to be loved and admired; the other wanted to be despised. One tried to make people better than they were; the other tore them down. One was careful to the point of hypochondria; the other reckless of his health and safety. There was Scott the considerate husband and Scott his wife's oppressor; the proud father and the father who embarrassed his daughter. The Scott Fitzgerald I knew best was the mature man, although Jekyll sometimes turned into Hyde. It was, of course, his drinking which brought on the transformation, when even his usually wan and self-contained expression changed into flushed anger. “Which is the real you?” I once asked him. And he replied, “The sober man.” -"The Real F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thirty-Five Years Later" (1976) by Sheilah Graham

Friday, October 31, 2014

"An Alcoholic Case" for Halloween, Jazz Age

Ray Milland as Don Birnam in "The Lost Weekend" (1945) directed by Billy Wilder

"Had the day really gone, had it really managed to pass, he was still sane, still alive? The room was cool, the sunlight had long since left the carpet, though he hadn’t realized it till now. He turned to look out the window. The sun had withdrawn also from the apartment building across the way, it was getting dark. Now what? What about the night, how was he going to survive it?— for he knew that sleep, in this keyed-up state, was beyond possibility. Or was Helen going to arrive and attempt again to rescue him from that night? Never! He would face a nightmare night of devils and creeping horror and shrieking empty bottles twenty times more dreadful than the dreadful day, rather than face Helen, rather than open the door to her. Let her ring the bell, let her ring her head off, he was beyond reach now. He clutched the arms of the chair, fixed his eye on the door, and waited for the bell to ring." -"The Lost Weekend" (1944) by Charles R. Jackson

"Some Halloween jokester had split the side windows of the bus and she shifted back to the Negro section in the rear for fear the glass might fall out. Two nurses she knew were waiting in the hall of Mrs Hixson's Agency. 'What kind of case have you been on?' 'Alcoholic,' she said. 'Gretta Hawks told me about it--you were on with that cartoonist who lives at the Forest Park Inn.' The phone rang in a continuous chime. [...] He was looking at the corner where he had thrown the bottle the night before. She stared at his handsome face, weak and defiant--afraid to turn even half-way because she knew that death was in that corner where he was looking. She knew death--she had heard it, smelt its unmistakable odour, but she had never seen it before it entered into anyone, and she knew this man saw it in the corner of his bathroom; that it was standing there looking at him while he spat from a feeble cough and rubbed the result into the braid of his trousers. It shone there crackling for a moment as evidence of the last gesture he ever made." -"An Alcoholic Case" (1937) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

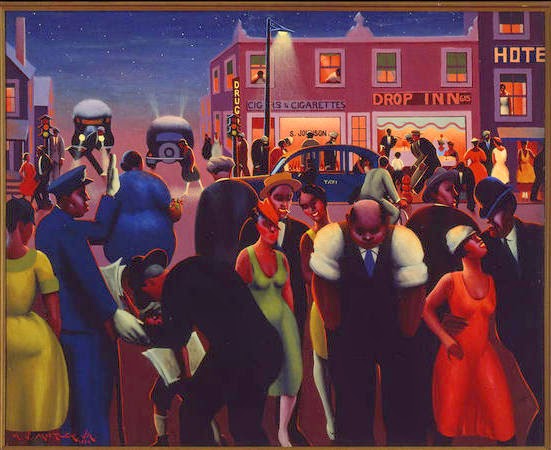

Artist Archibald J. Motley Jr.'s Jazz Age imagery on display at LACMA: Achibald J. Motley Jr. was an artist intrigued by the night. It is there in a large number of his paintings, which tap into the joys and dramas of life after dark, onstage and backstage, in the streets of Chicago or during a feverish nighttime church service. His neon-lighted scenes emerged from the Midwestern wing of the Harlem Renaissance, as the African American community asserted itself nearly a century ago as a major creative force in art, literature and music. "Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist," on exhibition through Feb. 1 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is the first wide-ranging survey of his vivid work since a 1991show at the Chicago History Museum.

With about 45 paintings, the LACMA show (which opened at Duke's Nasher Museum of Art) is not a full retrospective but represents "the highlights of an amazing career," says Powell. While the early portraits, Powell says, "deal with family and friends, 'Tongues (Holy Rollers)' is the extended family: The family of the community. The family of black folks at church, at the park, in clubs. It's all a big reflection on Jazz Age Chicago." The exhibition is organized into sections focused on his early portraits, commentary on race, his year in Paris, and Chicago street and night scenes. The later section includes the sound of vintage jazz recordings pumped into the room. While Motley's initial renown in art circles began to fade in the 1940s as interest grew in abstraction and attention focused even more on New York City, his work was rediscovered during the black arts movement of the '60s and '70s, Powell says. Source: www.latimes.com

"Had the day really gone, had it really managed to pass, he was still sane, still alive? The room was cool, the sunlight had long since left the carpet, though he hadn’t realized it till now. He turned to look out the window. The sun had withdrawn also from the apartment building across the way, it was getting dark. Now what? What about the night, how was he going to survive it?— for he knew that sleep, in this keyed-up state, was beyond possibility. Or was Helen going to arrive and attempt again to rescue him from that night? Never! He would face a nightmare night of devils and creeping horror and shrieking empty bottles twenty times more dreadful than the dreadful day, rather than face Helen, rather than open the door to her. Let her ring the bell, let her ring her head off, he was beyond reach now. He clutched the arms of the chair, fixed his eye on the door, and waited for the bell to ring." -"The Lost Weekend" (1944) by Charles R. Jackson

"Some Halloween jokester had split the side windows of the bus and she shifted back to the Negro section in the rear for fear the glass might fall out. Two nurses she knew were waiting in the hall of Mrs Hixson's Agency. 'What kind of case have you been on?' 'Alcoholic,' she said. 'Gretta Hawks told me about it--you were on with that cartoonist who lives at the Forest Park Inn.' The phone rang in a continuous chime. [...] He was looking at the corner where he had thrown the bottle the night before. She stared at his handsome face, weak and defiant--afraid to turn even half-way because she knew that death was in that corner where he was looking. She knew death--she had heard it, smelt its unmistakable odour, but she had never seen it before it entered into anyone, and she knew this man saw it in the corner of his bathroom; that it was standing there looking at him while he spat from a feeble cough and rubbed the result into the braid of his trousers. It shone there crackling for a moment as evidence of the last gesture he ever made." -"An Alcoholic Case" (1937) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Artist Archibald J. Motley Jr.'s Jazz Age imagery on display at LACMA: Achibald J. Motley Jr. was an artist intrigued by the night. It is there in a large number of his paintings, which tap into the joys and dramas of life after dark, onstage and backstage, in the streets of Chicago or during a feverish nighttime church service. His neon-lighted scenes emerged from the Midwestern wing of the Harlem Renaissance, as the African American community asserted itself nearly a century ago as a major creative force in art, literature and music. "Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist," on exhibition through Feb. 1 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is the first wide-ranging survey of his vivid work since a 1991show at the Chicago History Museum.

With about 45 paintings, the LACMA show (which opened at Duke's Nasher Museum of Art) is not a full retrospective but represents "the highlights of an amazing career," says Powell. While the early portraits, Powell says, "deal with family and friends, 'Tongues (Holy Rollers)' is the extended family: The family of the community. The family of black folks at church, at the park, in clubs. It's all a big reflection on Jazz Age Chicago." The exhibition is organized into sections focused on his early portraits, commentary on race, his year in Paris, and Chicago street and night scenes. The later section includes the sound of vintage jazz recordings pumped into the room. While Motley's initial renown in art circles began to fade in the 1940s as interest grew in abstraction and attention focused even more on New York City, his work was rediscovered during the black arts movement of the '60s and '70s, Powell says. Source: www.latimes.com

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

The Man with X-Ray Eyes: a cautionary tale for Halloween, "Premature Burial" (1962)

Halloween is a special time. It is the one time of year when everyone gives of themselves. What they give can be anything from candy to a scare. We thought this October, we here at Mania would give you 31 Days of Horror films. Get ready for 31 films that will run gauntlet from scary to campy.

From the opening score by Les Baxter to director Roger Corman’s final shock the Man with X-Ray Eyes (formerly known as X) is a time capsule of the Sixties B horror genre worth every penny Corman put on screen. Ray Milland portrays Dr. James Xavier, a man obsessed with discovering the secrets to better and clearer vision. His experiments are not to benefit mankind with better eyesight but to see past all that is hidden from the world and what lies beyond. Xavier believes that his visionary experiment will bring the medical field to a new level where doctors have the capabilities to be living x-ray machines.

It is this obsession that is his downfall and his own shortsightedness that will cause his self-experimentation to go horribly wrong. Really there isn’t anything new here in the realm of mad scientist plots. They go all the way back to Mary Shelly’s Doctor Victor Frankenstein. Man wants answers and will ignore the laws of both man and nature to find them, ending with one horrific conclusion. The Sixties were uncertain times. The United States was rediscovering itself in terms of what was acceptable or not for race, sex and freedom. Corman walks a tightrope by showing his perception of the era and how men and women saw each other instead of focusing on his original intent, a horror film. One example of how he accomplished this is at a swinging dance party after Xavier has the ability to see them without their clothes. Another example deals with how the poor and destitute see Xavier as their savior. He is reduced to performing parlor tricks with his eyes to make ends meet.

The ending is a bigger than expected finale given the budget and the era of the film. Corman doesn’t waste a single penny on screen and gives the audience a ride on a plot that has been done to death. The final moments are a brilliant conclusion and will leave no fan of the genre disappointed. The Man with X-Ray Eyes is a great cautionary tale and the perils of science and man’s quest for knowledge.

Source: www.mania.com

"Premature Burial" (1962) directed by Roger Corman, starring Ray Milland, Hazel Court and Heather Angel, based on a short story by Edgar Allan Poe (published in 1844 in The Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper).

Set in the early dark Victorian-era 1830s or '40s (also similar to Charles Dickens' fiction of rain-soaked London streets), we follow Guy Carrell (Ray Milland), who is obsessed with the fear of death. He is most obsessed with the fear of being buried alive. Though his fiancee Emily (Hazel Court) says he has nothing to be afraid of, he still thinks he will be buried alive (a common fear and in reality an occasional occurrence). So deluded, he seeks help from a few people, including his sister Kate (Heather Angel), but he still is haunted by the fear of death and the sense that someone close wants him dead.

From the opening score by Les Baxter to director Roger Corman’s final shock the Man with X-Ray Eyes (formerly known as X) is a time capsule of the Sixties B horror genre worth every penny Corman put on screen. Ray Milland portrays Dr. James Xavier, a man obsessed with discovering the secrets to better and clearer vision. His experiments are not to benefit mankind with better eyesight but to see past all that is hidden from the world and what lies beyond. Xavier believes that his visionary experiment will bring the medical field to a new level where doctors have the capabilities to be living x-ray machines.

It is this obsession that is his downfall and his own shortsightedness that will cause his self-experimentation to go horribly wrong. Really there isn’t anything new here in the realm of mad scientist plots. They go all the way back to Mary Shelly’s Doctor Victor Frankenstein. Man wants answers and will ignore the laws of both man and nature to find them, ending with one horrific conclusion. The Sixties were uncertain times. The United States was rediscovering itself in terms of what was acceptable or not for race, sex and freedom. Corman walks a tightrope by showing his perception of the era and how men and women saw each other instead of focusing on his original intent, a horror film. One example of how he accomplished this is at a swinging dance party after Xavier has the ability to see them without their clothes. Another example deals with how the poor and destitute see Xavier as their savior. He is reduced to performing parlor tricks with his eyes to make ends meet.

The ending is a bigger than expected finale given the budget and the era of the film. Corman doesn’t waste a single penny on screen and gives the audience a ride on a plot that has been done to death. The final moments are a brilliant conclusion and will leave no fan of the genre disappointed. The Man with X-Ray Eyes is a great cautionary tale and the perils of science and man’s quest for knowledge.

Source: www.mania.com

"Premature Burial" (1962) directed by Roger Corman, starring Ray Milland, Hazel Court and Heather Angel, based on a short story by Edgar Allan Poe (published in 1844 in The Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper).

Set in the early dark Victorian-era 1830s or '40s (also similar to Charles Dickens' fiction of rain-soaked London streets), we follow Guy Carrell (Ray Milland), who is obsessed with the fear of death. He is most obsessed with the fear of being buried alive. Though his fiancee Emily (Hazel Court) says he has nothing to be afraid of, he still thinks he will be buried alive (a common fear and in reality an occasional occurrence). So deluded, he seeks help from a few people, including his sister Kate (Heather Angel), but he still is haunted by the fear of death and the sense that someone close wants him dead.

Friday, October 24, 2014

Marlene Dietrich: exhibit on LACMA, Donald Spoto's biography

"It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily." —Marlene Dietrich in "Shanghai Express" (1932)

LACMA is currently hosting a fabulous new exhibit on Hollywood costume design called Hollywood Costume, running until March 2, 2015, at the Wilshire May Company building. Concurrently the LACMA Tuesday senior matinee has scheduled its monthly films built around a famed designer. October is devoted to Paramount's Travis Banton, who with Adrian (MGM), Orry-Kelly (Warner Brothers) and Edith Head (Paramount) helped create the gorgeous movie costumes of the Golden Age of Hollywood. Banton created the great Marlene Dietrich gowns that she wore through her '30s Paramount career.

Dietrich's first American film, Morocco, screened this week, and it was a revelation—not so much for the Dietrich costumes but for how the actress was first presented to American films audiences in 1930. Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo were icons and eternal symbols of glamour from the very beginning of their careers. Both actresses were foreign born stars (Germany and Sweden) whose status and popularity was more rarefied than home-grown product. Critics and big city audiences appreciated these beauties, but most Americans wanted Jean Harlow and Myrna Loy. Garbo was considered the actress, Dietrich the symbol of foreign mystery and allure.

Josef Von Sternberg had made Marlene Dietrich a star with the classic The Blue Angel. Watching this film today, it is hard to figure out how she became a legend. She was plump and not particularly alluring. Van Sternberg brought her to Hollywood, and together they made six films together that are revered today as classics. Von Sternberg convinced Dietrich to lose weight, and her glamorous image—created by striking camera work and inventive direction—was responsible for the icon known as Marlene Dietrich. Watching Morocco the other day was fascinating in that you could see Dietrich move from amateur to star as the film progresses. In the beginning Dietrich looks plump and unsure of herself in her two musical numbers. Later, as her obsession with legionnaire Gary Cooper increases, you see the transformation from minor actress to assured star. Morocco is a terrible movie but pretty campy, especially at the end when Marlene kicks off her high heals and staggers into the desert with the other female camp followers to stay with her man. Ironically, Dietrich received her only Oscar nomination for this kitschy role.

In just two short years, "Marlene Dietrich, icon extraordinaire" was born in Shanghai Express—probably the best of the Von Sternberg films. The baby fat is gone, the hair is longer and more lustrous, and her face has a sculpted look backed by feathers and luminous photography. As visually striking as the Von Sternberg films were, they threatened to destroy Dietrich the actress. By the end of the '30s she was called box-office poison and in dire need of a career change. She found it playing Frenchie in the great western/comedy Destry Rides Again with James Stewart. Dietrich was still glamorous, but she was alive and funny for the first time on-screen.

During the war years, Marlene Dietrich devoted herself to supporting the U.S. war effort against her homeland. She had famously turned down Adolf Hitler's offer to return to Germany as a superstar. Touring war zones and giving all her support to defeating Germany made her a legend in the United States and a pariah in her native land. Dietrich was given the Medal of Freedom by the U.S. in 1945. Marlene Dietrich became truly interesting as an actress after the the war. She may be the only actress from that era to actually look better as she got older.

In 1948, Dietrich gave her greatest performance in Billy Wilder's A Foreign Affair. At age 46 she looked better than she had in Morocco back in 1930. And her performance was staggering. Yet there was no Oscar nomination, and the film was so controversial that it vanished quickly. Loretta Young won the 1947 Best Actress award for The Farmer's Daughter. Dietrich should have romped home with this award for her spectacular performance. In 1950 she stole Alfred Hitchcock's Stagefright from a pallid Jane Wyman, and in 1957 gave another magnificent performance as Christine Vole in Billy Wilder's courtroom thriller Witness for the Prosecution. Playing the German wife of accused murderer Tyrone Power, Dietrich was amazing, still the glamour icon deep into her 50s.

One last great role came with her hysterical cameo in Orson Welles' Touch of Evil. Looking like she was doing retakes from her 1947 camp classic Golden Earrings, Dietrich had a field day as the all-knowing Tanya. Dietrich continued her career as a singer and sex symbol for the next 20 years. After a disastrous stage fall, she retreated to her Paris apartment and was a total recluse for the last 11 years of her life. Academy Award-winner Max Shell made a documentary about the fabulous star. Released in 1984, Marlene was extravagantly reviewed even though only Dietrich's voice was used as she refused to be photographed. As Norma Desmond exclaimed in Sunset Boulevard, "Great stars are ageless," but great stars like Dietrich were smart enough to retreat behind the legend. Marlene Dietrich is a gay icon not only because of her fabulous film career—her bisexual lifestyle is filled with enough famous lovers of both sexes to stagger the imagination.

Marlene Dietrich was the eternal symbol of beauty and glamor for almost 50 years. But if you have to pick just one Dietrich film to watch, get Billy Wilder's A Foreign Affair. It is all there—the voice, the face, great songs, gorgeous cinematography, brilliant Wilder dialog and the greatest performance the legend known as Marlene Dietrich ever gave. Source: www.frontiersla.com

Dietrich smoothly engineered an evening à deux at Horn Avenue, and soon there flourished an affair that was (at least for Cooper) as hot as Morocco itself. This was no real challenge for Dietrich, since Cooper, although married, readily succumbed to the offer; he had also been involved with Clara Bow and, even more seriously, with Lupe Velez. Of course, von Sternberg was not at all pleased with this new development, but he knew better than to complain. Some people can evoke from their lovers an attention that is frankly deferential. This ability Dietrich seems to have raised to the level of a fine art, for remarkably often in her life her lovers were not only grateful admirers but somehow felt bound to her.

Men were especially vulnerable to this, Cooper among them: for the remainder of Morocco, he was her devoted ally, far more ardent to please and attend her in life than in the story they were filming. Von Sternberg, though firmly out of this romantic running of the bulls, quietly raged with jealousy and resentment, according to both Dietrich (“They didn’t like each other . . . [it was] jealousy”) and actor Joel McCrea, a friend of Cooper’s (“Jo was jealous . . . and Cooper hated him”). But to make things more complicated still, Cooper soon had his own reasons for jealousy when he learned that Maurice Chevalier had briefly become a rival. Chevalier’s autobiography claims the friendship was “simply camaraderie,” but his wife used it as the basis for a successful divorce petition. It would be easy to regard Marlene Dietrich’s vigorous sexual life as irresponsible, frankly hedonistic or even symptomatic of an almost obsessive carnality. But her affairs, no matter how brief or nonexclusive, were always focussed and intense, never merely casual, anonymous trysts. Lavish in bestowing amatory favors, Dietrich in fact equated sex more with the offering of comfort —or perhaps more accurately, the complex, benevolent control she exerted in romances was her gratification. Sex was something nurturing she offered those she respected (like von Sternberg), those she thought were lonely (like Chevalier) or those she thought to be in need (like Cooper, who complained, poor man, that he was being nagged by both his wife and by Lupe Velez).

Essentially a woman of clear preferences and antipathies, Dietrich concealed none of them. She disliked most modern art (von Sternberg’s occasional tutorials notwithstanding), noodles, horse races, evangelism, fish, after-dinner speeches, politics, American sandwiches, opera and slang; she favored Punch and Judy shows, apple strudel, circus performers, speeding in an open roadster, pickles, perfumes, romantic novels by Sudermann and doleful poetry by Heine. There was, however, nothing about her of the Byronic heroine, and her attitude toward intimacy was a great deal simpler than von Sternberg’s, and without much reflection. “I had nothing to do with my birth,” she said around this time, “and I most likely will have nothing to do with my future. My philosophy of life is simply one of resignation.”

Her convictions, accordingly, were based simply on experience, and this had unequivocally taught her that Josef von Sternberg was certainly good for her. While he saw her as a beautiful woman who could wreak emotional havoc by simply being, he was at the same time one of the moths drawn ineluctably to her flame. Dietrich was an exciting woman whose eroticism was, to those she liked, neither cheaply accessible nor teasingly withheld. For von Sternberg, she also seemed to promise more than she at any one time delivered—not only more sensual satisfaction but also more artistic possibilities for her exploitation as an actress. However, intimacy revealed to von Sternberg another part of her nature: that there was perhaps nothing in her emotional life reserved for only one or even a dozen people she liked. And this realization prompted von Sternberg to withdraw.

The coolly detached seducer of the self-destructive man, she was an earthy woman who simply cavorted according to her nature (thus The Blue Angel). But the tarnished performer could also be a faithful follower (Morocco), a hooker with a curious higher morality (Dishonored), a weary traveler living by wit and charm (Shanghai Express), a mother devoted to her child (Blonde Venus). Although she always insisted her roles had nothing to do with her true character, the truth was just the opposite: they were in fact coded chapters in a kind of tribute-biography von Sternberg made of her, a series of essays that could have been called “All the Things You Are.” But he also saw her, in everyday life, as capricious, even sometimes shallow; his fantasy about her was therefore being chastened and his goddess revealed as thoroughly human, frail and fallible.

Dietrich was becoming more and more blunt in pursuing actresses she found attractive; among them were Paramount’s Carole Lombard and Frances Dee, whose unregenerate heterosexuality did not dissuade Dietrich from her usual stratagems of flower deliveries and romantic blandishments. Lombard, a beautiful, brash blonde, was unamused: “If you want something,” she told Dietrich after finding one too many sweet notes and posies in her dressing room at Paramount, “you come on down when I’m there. I’m not going to chase you.”

Dietrich took Hemingway as something of a counselor and father-figure, calling him (as did others) her “Papa.” She was most of all one of his buddies, and in this regard the relationship was perhaps unique in his life. By a kind of tacit common consent, they were never lovers—a situation that might have aborted friendship with this man who simultaneously revered and feared women. His “loveliest dreams,” as he said, were often of Dietrich, who was “awfully nice in dreams”—a sentiment worthy of von Sternberg. With Dietrich, Hemingway could simultaneously enjoy the nurturing adulation of a beautiful and famous woman and the matey fellowship of someone who never threatened him by demanding sex; in this way, Marlene Dietrich was the ideal Hemingway heroine. He called her 'The Kraut'.

Dietrich’s cavalier independence and the role of lover primus inter pares was finally too much for Jean Gabin; he married the French actress Maria Mauban. This was a devastating blow to Dietrich, who could never understand why a man she still loved (or ever had loved) would commit to another woman. When Robert Kennedy asked her, at a Washington luncheon in 1963, why she said she left Jean Gabin, she replied, “Because he wanted to marry me. I hate marriage. It is an immoral institution. But he still loves me.” The Gabin affair ended in 1946. Dietrich now had no prospects of European film work and therefore accepted an offer from Hollywood to appear in a film called Golden Earrings. Because she had been absent from Hollywood three full years (and had not starred in a successful film since 1939), Leisen had to convince Paramount that Dietrich was the right choice to play Lydia, a vulgar but seductive Middle European gypsy who helps a British intelligence officer smuggle a poison gas formula out of Nazi Germany just before the war by disguising him as her peasant husband. When she was first offered the role, Dietrich was still in Europe and visited gypsy camps to see how the women looked, dressed and behaved.

Now at the studio for wardrobe and makeup tests, she assured Leisen she would play Lydia with complete fidelity to realism—to European neorealism, in fact, which flinched at nothing. This she did stonishingly well, for although Dietrich could not of course completely abandon her pretension to youthful beauty (nor would the studio have desired it), she dispatched the role of a greasy, sloppy gypsy with the kind of fresh comic panache not seen since her Frenchy in Destry Rides Again.

As a sex-starved wench, she swoops down on the stuffy hero played by Ray Milland, supervising his transformation into a Hungarian peasant. Munching bread, gnawing on a fish-head supper, spitting for good luck, diving for Milland’s lips and chest, she is the complete, manhungry virago—at once crude, funny and sensuous throughout the aridly incredible narrative. “You look like a wild bull!” she whispers to Milland after she has finished with his disguising makeup, pierced his ears and clipped on the golden earrings; then she nearly growls, “The girls—will—go—mad—for you!” Often resembling the seductive young Gloria Swanson, Dietrich does not simply breathe in this picture; she seems to exhale fire.

But the appealing comic nonsense of the completed Golden Earrings did not apply to the rigors of production, for there were bitter feuds. Milland, who had just won an Oscar playing an alcoholic in Billy Wilder’s harrowing film The Lost Weekend, disliked Dietrich and feared she would steal the picture (which she handily did). He also found her commitment to realism somewhat revolting—especially in the eating scene, when she repeatedly stuck a fish in her mouth, sucked out the eye, pulled off the head, swallowed it and (after Leisen had shot the scene) promptly stuck her finger in her throat and vomited. The Legion of Decency’s censure (she could not keep her hands off Milland) was officially an acute embarrassment for the studio, although it was also splendid free publicity: the picture returned three million dollars in the next two years.

From Paris that summer of 1947, Dietrich wrote to her Paramount hairdresser, Nellie Manley, that she was “living quietly at the Hotel Georges V, cooking whatever can be cooked. The attitude and the feelings of the people are not as good as they were during the war. It is depressing, but not hopeless.” Her fortunes improved that August, when Billy Wilder stopped in Paris to visit her after filming exterior shots for a forthcoming “black comedy” about life in occupied postwar Berlin; he offered Dietrich the role of Erika von Schlütow in the picture, to be called A Foreign Affair. At first she rejected it, hesitating to play the German mistress of an American army officer who loses him to a winsome visiting congresswoman and is then taken away by military police after her Nazi past is revealed.

With his patented brand of acerbic moral cynicism, Wilder had prepared A Foreign Affair as a satiric criticism of widespread military corruption amid the ruins of Berlin, of the Allied involvement in a shameful black market, and of the self-righteous abuse of German civilians by occupying American soldiers. When filming began in December, Dietrich’s co-star as the prissy, investigating congresswoman was Jean Arthur; the leading man was John Lund; and the pianist in the cabaret was none other than Hollander himself, invited in tribute to his long association as Dietrich’s composer.

Like Pasternak, Wilder understood the value of deglamorizing Dietrich. Her first appearance in A Foreign Affair goes beyond anything in Golden Earrings: her hair is unbrushed, her face smirched with toothpaste, water trickles from her mouth as she brushes and gargles. This character is no Amy Jolly, no Concha Perez. As the story proceeds, it becomes clear that Erika can manipulate American officers as easily as she did Nazis, one of whom was her attended as a fashionable companion. But she has suffered privately, socially and by postwar deprivation for her guilty past; her act at the Lorelei cabaret, singing “Black Market” and “The Ruins of Berlin,” expresses her cool cynicism, her distrust of any nation’s claim to moral supremacy and her necessary, fearful suspicion of everyone.

The role was perfect for Dietrich, for she had been long confirmed by Hollywood as von Sternberg’s icon of the tarnished woman masked with pain and capable of love and all of whom she easily the sudden acknowledgment of her own need for tenderness and forgiveness— indeed, for redemption from the past. “I knew,” Wilder said years later, “that whatever obsession she had with her appearance, she was also a thorough professional. From the time she met von Sternberg she had always been very interested in his magic tricks with the camera—tricks she tried to teach every cameraman in later pictures.” -"Blue Angel: the Life of Marlene Dietrich" (2000) by Donald Spoto

LACMA is currently hosting a fabulous new exhibit on Hollywood costume design called Hollywood Costume, running until March 2, 2015, at the Wilshire May Company building. Concurrently the LACMA Tuesday senior matinee has scheduled its monthly films built around a famed designer. October is devoted to Paramount's Travis Banton, who with Adrian (MGM), Orry-Kelly (Warner Brothers) and Edith Head (Paramount) helped create the gorgeous movie costumes of the Golden Age of Hollywood. Banton created the great Marlene Dietrich gowns that she wore through her '30s Paramount career.

Dietrich's first American film, Morocco, screened this week, and it was a revelation—not so much for the Dietrich costumes but for how the actress was first presented to American films audiences in 1930. Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo were icons and eternal symbols of glamour from the very beginning of their careers. Both actresses were foreign born stars (Germany and Sweden) whose status and popularity was more rarefied than home-grown product. Critics and big city audiences appreciated these beauties, but most Americans wanted Jean Harlow and Myrna Loy. Garbo was considered the actress, Dietrich the symbol of foreign mystery and allure.

Josef Von Sternberg had made Marlene Dietrich a star with the classic The Blue Angel. Watching this film today, it is hard to figure out how she became a legend. She was plump and not particularly alluring. Van Sternberg brought her to Hollywood, and together they made six films together that are revered today as classics. Von Sternberg convinced Dietrich to lose weight, and her glamorous image—created by striking camera work and inventive direction—was responsible for the icon known as Marlene Dietrich. Watching Morocco the other day was fascinating in that you could see Dietrich move from amateur to star as the film progresses. In the beginning Dietrich looks plump and unsure of herself in her two musical numbers. Later, as her obsession with legionnaire Gary Cooper increases, you see the transformation from minor actress to assured star. Morocco is a terrible movie but pretty campy, especially at the end when Marlene kicks off her high heals and staggers into the desert with the other female camp followers to stay with her man. Ironically, Dietrich received her only Oscar nomination for this kitschy role.

In just two short years, "Marlene Dietrich, icon extraordinaire" was born in Shanghai Express—probably the best of the Von Sternberg films. The baby fat is gone, the hair is longer and more lustrous, and her face has a sculpted look backed by feathers and luminous photography. As visually striking as the Von Sternberg films were, they threatened to destroy Dietrich the actress. By the end of the '30s she was called box-office poison and in dire need of a career change. She found it playing Frenchie in the great western/comedy Destry Rides Again with James Stewart. Dietrich was still glamorous, but she was alive and funny for the first time on-screen.

During the war years, Marlene Dietrich devoted herself to supporting the U.S. war effort against her homeland. She had famously turned down Adolf Hitler's offer to return to Germany as a superstar. Touring war zones and giving all her support to defeating Germany made her a legend in the United States and a pariah in her native land. Dietrich was given the Medal of Freedom by the U.S. in 1945. Marlene Dietrich became truly interesting as an actress after the the war. She may be the only actress from that era to actually look better as she got older.

In 1948, Dietrich gave her greatest performance in Billy Wilder's A Foreign Affair. At age 46 she looked better than she had in Morocco back in 1930. And her performance was staggering. Yet there was no Oscar nomination, and the film was so controversial that it vanished quickly. Loretta Young won the 1947 Best Actress award for The Farmer's Daughter. Dietrich should have romped home with this award for her spectacular performance. In 1950 she stole Alfred Hitchcock's Stagefright from a pallid Jane Wyman, and in 1957 gave another magnificent performance as Christine Vole in Billy Wilder's courtroom thriller Witness for the Prosecution. Playing the German wife of accused murderer Tyrone Power, Dietrich was amazing, still the glamour icon deep into her 50s.

One last great role came with her hysterical cameo in Orson Welles' Touch of Evil. Looking like she was doing retakes from her 1947 camp classic Golden Earrings, Dietrich had a field day as the all-knowing Tanya. Dietrich continued her career as a singer and sex symbol for the next 20 years. After a disastrous stage fall, she retreated to her Paris apartment and was a total recluse for the last 11 years of her life. Academy Award-winner Max Shell made a documentary about the fabulous star. Released in 1984, Marlene was extravagantly reviewed even though only Dietrich's voice was used as she refused to be photographed. As Norma Desmond exclaimed in Sunset Boulevard, "Great stars are ageless," but great stars like Dietrich were smart enough to retreat behind the legend. Marlene Dietrich is a gay icon not only because of her fabulous film career—her bisexual lifestyle is filled with enough famous lovers of both sexes to stagger the imagination.

Marlene Dietrich was the eternal symbol of beauty and glamor for almost 50 years. But if you have to pick just one Dietrich film to watch, get Billy Wilder's A Foreign Affair. It is all there—the voice, the face, great songs, gorgeous cinematography, brilliant Wilder dialog and the greatest performance the legend known as Marlene Dietrich ever gave. Source: www.frontiersla.com

Dietrich smoothly engineered an evening à deux at Horn Avenue, and soon there flourished an affair that was (at least for Cooper) as hot as Morocco itself. This was no real challenge for Dietrich, since Cooper, although married, readily succumbed to the offer; he had also been involved with Clara Bow and, even more seriously, with Lupe Velez. Of course, von Sternberg was not at all pleased with this new development, but he knew better than to complain. Some people can evoke from their lovers an attention that is frankly deferential. This ability Dietrich seems to have raised to the level of a fine art, for remarkably often in her life her lovers were not only grateful admirers but somehow felt bound to her.

Men were especially vulnerable to this, Cooper among them: for the remainder of Morocco, he was her devoted ally, far more ardent to please and attend her in life than in the story they were filming. Von Sternberg, though firmly out of this romantic running of the bulls, quietly raged with jealousy and resentment, according to both Dietrich (“They didn’t like each other . . . [it was] jealousy”) and actor Joel McCrea, a friend of Cooper’s (“Jo was jealous . . . and Cooper hated him”). But to make things more complicated still, Cooper soon had his own reasons for jealousy when he learned that Maurice Chevalier had briefly become a rival. Chevalier’s autobiography claims the friendship was “simply camaraderie,” but his wife used it as the basis for a successful divorce petition. It would be easy to regard Marlene Dietrich’s vigorous sexual life as irresponsible, frankly hedonistic or even symptomatic of an almost obsessive carnality. But her affairs, no matter how brief or nonexclusive, were always focussed and intense, never merely casual, anonymous trysts. Lavish in bestowing amatory favors, Dietrich in fact equated sex more with the offering of comfort —or perhaps more accurately, the complex, benevolent control she exerted in romances was her gratification. Sex was something nurturing she offered those she respected (like von Sternberg), those she thought were lonely (like Chevalier) or those she thought to be in need (like Cooper, who complained, poor man, that he was being nagged by both his wife and by Lupe Velez).

Essentially a woman of clear preferences and antipathies, Dietrich concealed none of them. She disliked most modern art (von Sternberg’s occasional tutorials notwithstanding), noodles, horse races, evangelism, fish, after-dinner speeches, politics, American sandwiches, opera and slang; she favored Punch and Judy shows, apple strudel, circus performers, speeding in an open roadster, pickles, perfumes, romantic novels by Sudermann and doleful poetry by Heine. There was, however, nothing about her of the Byronic heroine, and her attitude toward intimacy was a great deal simpler than von Sternberg’s, and without much reflection. “I had nothing to do with my birth,” she said around this time, “and I most likely will have nothing to do with my future. My philosophy of life is simply one of resignation.”

Her convictions, accordingly, were based simply on experience, and this had unequivocally taught her that Josef von Sternberg was certainly good for her. While he saw her as a beautiful woman who could wreak emotional havoc by simply being, he was at the same time one of the moths drawn ineluctably to her flame. Dietrich was an exciting woman whose eroticism was, to those she liked, neither cheaply accessible nor teasingly withheld. For von Sternberg, she also seemed to promise more than she at any one time delivered—not only more sensual satisfaction but also more artistic possibilities for her exploitation as an actress. However, intimacy revealed to von Sternberg another part of her nature: that there was perhaps nothing in her emotional life reserved for only one or even a dozen people she liked. And this realization prompted von Sternberg to withdraw.

The coolly detached seducer of the self-destructive man, she was an earthy woman who simply cavorted according to her nature (thus The Blue Angel). But the tarnished performer could also be a faithful follower (Morocco), a hooker with a curious higher morality (Dishonored), a weary traveler living by wit and charm (Shanghai Express), a mother devoted to her child (Blonde Venus). Although she always insisted her roles had nothing to do with her true character, the truth was just the opposite: they were in fact coded chapters in a kind of tribute-biography von Sternberg made of her, a series of essays that could have been called “All the Things You Are.” But he also saw her, in everyday life, as capricious, even sometimes shallow; his fantasy about her was therefore being chastened and his goddess revealed as thoroughly human, frail and fallible.

Dietrich was becoming more and more blunt in pursuing actresses she found attractive; among them were Paramount’s Carole Lombard and Frances Dee, whose unregenerate heterosexuality did not dissuade Dietrich from her usual stratagems of flower deliveries and romantic blandishments. Lombard, a beautiful, brash blonde, was unamused: “If you want something,” she told Dietrich after finding one too many sweet notes and posies in her dressing room at Paramount, “you come on down when I’m there. I’m not going to chase you.”

Dietrich took Hemingway as something of a counselor and father-figure, calling him (as did others) her “Papa.” She was most of all one of his buddies, and in this regard the relationship was perhaps unique in his life. By a kind of tacit common consent, they were never lovers—a situation that might have aborted friendship with this man who simultaneously revered and feared women. His “loveliest dreams,” as he said, were often of Dietrich, who was “awfully nice in dreams”—a sentiment worthy of von Sternberg. With Dietrich, Hemingway could simultaneously enjoy the nurturing adulation of a beautiful and famous woman and the matey fellowship of someone who never threatened him by demanding sex; in this way, Marlene Dietrich was the ideal Hemingway heroine. He called her 'The Kraut'.

Dietrich’s cavalier independence and the role of lover primus inter pares was finally too much for Jean Gabin; he married the French actress Maria Mauban. This was a devastating blow to Dietrich, who could never understand why a man she still loved (or ever had loved) would commit to another woman. When Robert Kennedy asked her, at a Washington luncheon in 1963, why she said she left Jean Gabin, she replied, “Because he wanted to marry me. I hate marriage. It is an immoral institution. But he still loves me.” The Gabin affair ended in 1946. Dietrich now had no prospects of European film work and therefore accepted an offer from Hollywood to appear in a film called Golden Earrings. Because she had been absent from Hollywood three full years (and had not starred in a successful film since 1939), Leisen had to convince Paramount that Dietrich was the right choice to play Lydia, a vulgar but seductive Middle European gypsy who helps a British intelligence officer smuggle a poison gas formula out of Nazi Germany just before the war by disguising him as her peasant husband. When she was first offered the role, Dietrich was still in Europe and visited gypsy camps to see how the women looked, dressed and behaved.

Now at the studio for wardrobe and makeup tests, she assured Leisen she would play Lydia with complete fidelity to realism—to European neorealism, in fact, which flinched at nothing. This she did stonishingly well, for although Dietrich could not of course completely abandon her pretension to youthful beauty (nor would the studio have desired it), she dispatched the role of a greasy, sloppy gypsy with the kind of fresh comic panache not seen since her Frenchy in Destry Rides Again.

As a sex-starved wench, she swoops down on the stuffy hero played by Ray Milland, supervising his transformation into a Hungarian peasant. Munching bread, gnawing on a fish-head supper, spitting for good luck, diving for Milland’s lips and chest, she is the complete, manhungry virago—at once crude, funny and sensuous throughout the aridly incredible narrative. “You look like a wild bull!” she whispers to Milland after she has finished with his disguising makeup, pierced his ears and clipped on the golden earrings; then she nearly growls, “The girls—will—go—mad—for you!” Often resembling the seductive young Gloria Swanson, Dietrich does not simply breathe in this picture; she seems to exhale fire.

But the appealing comic nonsense of the completed Golden Earrings did not apply to the rigors of production, for there were bitter feuds. Milland, who had just won an Oscar playing an alcoholic in Billy Wilder’s harrowing film The Lost Weekend, disliked Dietrich and feared she would steal the picture (which she handily did). He also found her commitment to realism somewhat revolting—especially in the eating scene, when she repeatedly stuck a fish in her mouth, sucked out the eye, pulled off the head, swallowed it and (after Leisen had shot the scene) promptly stuck her finger in her throat and vomited. The Legion of Decency’s censure (she could not keep her hands off Milland) was officially an acute embarrassment for the studio, although it was also splendid free publicity: the picture returned three million dollars in the next two years.

From Paris that summer of 1947, Dietrich wrote to her Paramount hairdresser, Nellie Manley, that she was “living quietly at the Hotel Georges V, cooking whatever can be cooked. The attitude and the feelings of the people are not as good as they were during the war. It is depressing, but not hopeless.” Her fortunes improved that August, when Billy Wilder stopped in Paris to visit her after filming exterior shots for a forthcoming “black comedy” about life in occupied postwar Berlin; he offered Dietrich the role of Erika von Schlütow in the picture, to be called A Foreign Affair. At first she rejected it, hesitating to play the German mistress of an American army officer who loses him to a winsome visiting congresswoman and is then taken away by military police after her Nazi past is revealed.

With his patented brand of acerbic moral cynicism, Wilder had prepared A Foreign Affair as a satiric criticism of widespread military corruption amid the ruins of Berlin, of the Allied involvement in a shameful black market, and of the self-righteous abuse of German civilians by occupying American soldiers. When filming began in December, Dietrich’s co-star as the prissy, investigating congresswoman was Jean Arthur; the leading man was John Lund; and the pianist in the cabaret was none other than Hollander himself, invited in tribute to his long association as Dietrich’s composer.

Like Pasternak, Wilder understood the value of deglamorizing Dietrich. Her first appearance in A Foreign Affair goes beyond anything in Golden Earrings: her hair is unbrushed, her face smirched with toothpaste, water trickles from her mouth as she brushes and gargles. This character is no Amy Jolly, no Concha Perez. As the story proceeds, it becomes clear that Erika can manipulate American officers as easily as she did Nazis, one of whom was her attended as a fashionable companion. But she has suffered privately, socially and by postwar deprivation for her guilty past; her act at the Lorelei cabaret, singing “Black Market” and “The Ruins of Berlin,” expresses her cool cynicism, her distrust of any nation’s claim to moral supremacy and her necessary, fearful suspicion of everyone.

The role was perfect for Dietrich, for she had been long confirmed by Hollywood as von Sternberg’s icon of the tarnished woman masked with pain and capable of love and all of whom she easily the sudden acknowledgment of her own need for tenderness and forgiveness— indeed, for redemption from the past. “I knew,” Wilder said years later, “that whatever obsession she had with her appearance, she was also a thorough professional. From the time she met von Sternberg she had always been very interested in his magic tricks with the camera—tricks she tried to teach every cameraman in later pictures.” -"Blue Angel: the Life of Marlene Dietrich" (2000) by Donald Spoto

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

_02.jpg)

_by_Don_English.png)

_02.jpg)

.jpg)