"The Crooked Way" directed by Robert Florey in 1949, starring John Payne, Ellen Drew and Sonny Tufts (Full Movie)

Between 1952 and 1957, Phil Karlson made several films noirs that characterized the changing manner of noir expression in the fifties: Scandal Sheet -based on Sam Fuller’s novel The Dark Page- (1952), Kansas City Confidential (1952), 99 River Street (1953), Hell’s Island (1955), Tight Spot (1955), The Phenix City Story (1955), The Brothers Rico (1957). Karlson used the evocative lighting of cinematographers Burnett Guffey (Scandal Sheet, Tight Spot, The Brothers Rico), George Diskant (Kansas City Confidential), and Franz Planer (99 River Street) to display a classical chiaroscuro richness in many sequences while using on-location sets and story themes prevalent in many crime dramas of the decade.

Between 1952 and 1957, Phil Karlson made several films noirs that characterized the changing manner of noir expression in the fifties: Scandal Sheet -based on Sam Fuller’s novel The Dark Page- (1952), Kansas City Confidential (1952), 99 River Street (1953), Hell’s Island (1955), Tight Spot (1955), The Phenix City Story (1955), The Brothers Rico (1957). Karlson used the evocative lighting of cinematographers Burnett Guffey (Scandal Sheet, Tight Spot, The Brothers Rico), George Diskant (Kansas City Confidential), and Franz Planer (99 River Street) to display a classical chiaroscuro richness in many sequences while using on-location sets and story themes prevalent in many crime dramas of the decade. His leading noir characters, always men and best portrayed by John Payne, who starred in three Karlson noirs— Kansas City Confidential, 99 River Street, and Hell’s Island—are invariably trapped by a flawed past in a web of present-day circumstances that generate fear of being caught for a crime they did not do. Indeed, the Karlson-Payne films, particularly Kansas City Confidential and 99 River Street, are among the decade’s most compelling cinematic correlatives to the terror evoked in Cornell Woolrich’s fiction; yet this interior turmoil is contained in actions governed by a fifties milieu of often brutal criminal activity now seen as intrinsic to America’s social foundation.

His leading noir characters, always men and best portrayed by John Payne, who starred in three Karlson noirs— Kansas City Confidential, 99 River Street, and Hell’s Island—are invariably trapped by a flawed past in a web of present-day circumstances that generate fear of being caught for a crime they did not do. Indeed, the Karlson-Payne films, particularly Kansas City Confidential and 99 River Street, are among the decade’s most compelling cinematic correlatives to the terror evoked in Cornell Woolrich’s fiction; yet this interior turmoil is contained in actions governed by a fifties milieu of often brutal criminal activity now seen as intrinsic to America’s social foundation. The past that haunts the present, that serves as a component in foreboding a terrible future, is the central nightmare in Karlson’s world. In both films, the Payne characters come into the stories with lives broken in the past that leave them bitter but stronger, and quite without warning they find themselves in a harsh battle with fate. Joe Rolfe’s frame-up in Kansas City Confidential enrages him as he seeks to exonerate his appearance of guilt in a bank robbery. He did time on a gambling rap, and the suspicion because of this past lands him in jail, where the striking pattern of vertical lines reflected in a low-lit jail cell reinforces the terror of an arbitrary world where you can be picked up for nothing you have done wrong.

The past that haunts the present, that serves as a component in foreboding a terrible future, is the central nightmare in Karlson’s world. In both films, the Payne characters come into the stories with lives broken in the past that leave them bitter but stronger, and quite without warning they find themselves in a harsh battle with fate. Joe Rolfe’s frame-up in Kansas City Confidential enrages him as he seeks to exonerate his appearance of guilt in a bank robbery. He did time on a gambling rap, and the suspicion because of this past lands him in jail, where the striking pattern of vertical lines reflected in a low-lit jail cell reinforces the terror of an arbitrary world where you can be picked up for nothing you have done wrong. Released, Rolfe assumes the guise of one of the robbers —unknown, as they are, to each other— and tracks down his cohorts one by one, determined to find the robbery’s mastermind. As the Mexican authorities shoot one of them, Rolfe, but feet away, watches as Pete Harris (beautifully played by an early Jack Elam) crumples slowly to his death; Rolfe is dreading the man’s last-breath opportunity to betray Rolfe’s true identity. When he is beaten by the other two, Kane and Romano, at their rendezvous on a Caribbean island, low-angle shots in low-key lighting maintain the tension of how much physical punishment Rolfe can take without relenting. These moments are tests in Karlson’s world, as much of violence as of the psychological resilience his characters need to withstand persecution. And invariably they are shown in close shots. Unlike the close-up, which is inspective, the close shot for filmmakers like Karlson is isolating: men take their punches, and confront their fear in the image of their battered, sweaty faces —alone.

Released, Rolfe assumes the guise of one of the robbers —unknown, as they are, to each other— and tracks down his cohorts one by one, determined to find the robbery’s mastermind. As the Mexican authorities shoot one of them, Rolfe, but feet away, watches as Pete Harris (beautifully played by an early Jack Elam) crumples slowly to his death; Rolfe is dreading the man’s last-breath opportunity to betray Rolfe’s true identity. When he is beaten by the other two, Kane and Romano, at their rendezvous on a Caribbean island, low-angle shots in low-key lighting maintain the tension of how much physical punishment Rolfe can take without relenting. These moments are tests in Karlson’s world, as much of violence as of the psychological resilience his characters need to withstand persecution. And invariably they are shown in close shots. Unlike the close-up, which is inspective, the close shot for filmmakers like Karlson is isolating: men take their punches, and confront their fear in the image of their battered, sweaty faces —alone. 99 River Street is Karlson’s best film noir and one that defines well the defeated noir protagonist in the postwar era. Ernie Driscoll is a social representative of a world that encourages success and its rewards. As a frustrated man of lost possibilities, he knows the exhilaration of having “a chance at the top,” as he tells Linda. “It’s the most important thing in the world.” A victim of an eye injury in the boxing ring, he has been reduced to a person without accomplishment in a world that “knows you only if it can exploit you.” He drives a taxi now, and his unfaithful wife cannot stand it. Driscoll, like Rolfe, is no stranger to violence, but unlike him, and poignantly so, he has not learned callousness from his setbacks.

99 River Street is Karlson’s best film noir and one that defines well the defeated noir protagonist in the postwar era. Ernie Driscoll is a social representative of a world that encourages success and its rewards. As a frustrated man of lost possibilities, he knows the exhilaration of having “a chance at the top,” as he tells Linda. “It’s the most important thing in the world.” A victim of an eye injury in the boxing ring, he has been reduced to a person without accomplishment in a world that “knows you only if it can exploit you.” He drives a taxi now, and his unfaithful wife cannot stand it. Driscoll, like Rolfe, is no stranger to violence, but unlike him, and poignantly so, he has not learned callousness from his setbacks. Ernie and his actress-friend Linda James, with whom he shares cups of drugstore coffee and sympathy, are characters attenuated by bad breaks in life in the manner that only creative people recognize. Their sensitivity, encouraged by performance —he in the fight ring and she on stage— exempts them from a total submission to noir hell. They function, as dreamers do, in a world all too often out of touch with their needs.

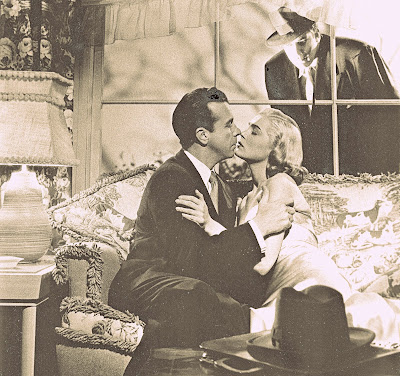

Ernie and his actress-friend Linda James, with whom he shares cups of drugstore coffee and sympathy, are characters attenuated by bad breaks in life in the manner that only creative people recognize. Their sensitivity, encouraged by performance —he in the fight ring and she on stage— exempts them from a total submission to noir hell. They function, as dreamers do, in a world all too often out of touch with their needs. It is interesting that Linda deceives Ernie into believing she killed a man in rage and self-defense for an acting audition, but she delivers her greatest “performance” (certainly the best screen time of Evelyn Keyes’s career) when she attempts to seduce Pauline Driscoll’s killer with what must surely be one of the most erotically charged scenes in American cinema up to then, replete with insinuations of welcome rough sex. Her ruse, filmed in a medium-close panning shot of seemingly endless length, displays a rare moment of the metamorphic noir woman, a creature here who performs against her type to reveal a nonetheless compelling, dark side of her personality. “In a work of art intensity and speed can be creative forces, generating beauty and significance; outside of art, they can be, and often are, destructive,” wrote Jack Shadoian of the film. “99 River Street uses the American dynamism to condemn it; this is where it and other films of its period differ from similar films of the thirties and forties. Their insistence, often to the point of exaggeration, is, whether consciously or not, a moral one... Yet films like 99 River Street have no obvious moral ax to grind — one has to feel their bitterness. -"Street with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film Noir" (2002) by Andrew Dickos

It is interesting that Linda deceives Ernie into believing she killed a man in rage and self-defense for an acting audition, but she delivers her greatest “performance” (certainly the best screen time of Evelyn Keyes’s career) when she attempts to seduce Pauline Driscoll’s killer with what must surely be one of the most erotically charged scenes in American cinema up to then, replete with insinuations of welcome rough sex. Her ruse, filmed in a medium-close panning shot of seemingly endless length, displays a rare moment of the metamorphic noir woman, a creature here who performs against her type to reveal a nonetheless compelling, dark side of her personality. “In a work of art intensity and speed can be creative forces, generating beauty and significance; outside of art, they can be, and often are, destructive,” wrote Jack Shadoian of the film. “99 River Street uses the American dynamism to condemn it; this is where it and other films of its period differ from similar films of the thirties and forties. Their insistence, often to the point of exaggeration, is, whether consciously or not, a moral one... Yet films like 99 River Street have no obvious moral ax to grind — one has to feel their bitterness. -"Street with No Name: A History of the Classic American Film Noir" (2002) by Andrew Dickos John Payne in "The Crooked Way" (1949) directed by Robert Florey

John Payne in "The Crooked Way" (1949) directed by Robert Florey Nathaniel Rich believes that dread is the subject of noir. Guilt better explains the boomerang effect of many of the best noirs in which the investigator must seek his own guilty self, as in "Scandal Sheet" and "The Crooked Way"; As Jack Shadoian puts it, “society is the gangster.” Film noir then can be defined by a subject, a locale and a character. Its subject is crime, almost always a murder but sometimes a theft. Its locale is the contemporary world, usually a city at night. Its character is a fallible or tarnished man or woman. He might be a supporting character, an insurance investigator such as Edward G. Robinson in Double Indemnity or Edmond O’Brien in The Killers. He might be a reporter, such as John Derek in Scandal Sheet or a returning veteran, keen on discovering what happened to a friend or relative, as in "Cornered" (1945), "Act of Violence", and "Dead Reckoning", both of 1947. Not a few noir heroes are amnesiacs carrying out an investigation leading to themselves, such as John Hodiak in "Somewhere in the Night" (1946), and John Payne in "The Crooked Way" (1949) -This is pure noir, featuring an amnesiac vet with a criminal past that seeks him out. John Alton’s superb inematography amplifies the noir plot.

Nathaniel Rich believes that dread is the subject of noir. Guilt better explains the boomerang effect of many of the best noirs in which the investigator must seek his own guilty self, as in "Scandal Sheet" and "The Crooked Way"; As Jack Shadoian puts it, “society is the gangster.” Film noir then can be defined by a subject, a locale and a character. Its subject is crime, almost always a murder but sometimes a theft. Its locale is the contemporary world, usually a city at night. Its character is a fallible or tarnished man or woman. He might be a supporting character, an insurance investigator such as Edward G. Robinson in Double Indemnity or Edmond O’Brien in The Killers. He might be a reporter, such as John Derek in Scandal Sheet or a returning veteran, keen on discovering what happened to a friend or relative, as in "Cornered" (1945), "Act of Violence", and "Dead Reckoning", both of 1947. Not a few noir heroes are amnesiacs carrying out an investigation leading to themselves, such as John Hodiak in "Somewhere in the Night" (1946), and John Payne in "The Crooked Way" (1949) -This is pure noir, featuring an amnesiac vet with a criminal past that seeks him out. John Alton’s superb inematography amplifies the noir plot. 99 River Street (1953): John Payne, an ex-boxer, has an anger management problem. When his unfaithful wife is murdered, he becomes the chief suspect. Nobody is on the level, even Keyes, an actress, who fakes a murder to get a part in a play. Jack Lambert, an icon of a hood, makes the proceedings even more sinister. That male anxieties can only be allayed by women’s return to domesticity gets full support in this film. Keyes gives up her profession as an actress to be the happy wife of her gas station operator husband. -"What is Film Noir?" by William Park (2011)

99 River Street (1953): John Payne, an ex-boxer, has an anger management problem. When his unfaithful wife is murdered, he becomes the chief suspect. Nobody is on the level, even Keyes, an actress, who fakes a murder to get a part in a play. Jack Lambert, an icon of a hood, makes the proceedings even more sinister. That male anxieties can only be allayed by women’s return to domesticity gets full support in this film. Keyes gives up her profession as an actress to be the happy wife of her gas station operator husband. -"What is Film Noir?" by William Park (2011) John Payne and director Phil Karlson in the celebration of Mary Murphy´s birthday on the set of Hell´s Island (1955)

John Payne and director Phil Karlson in the celebration of Mary Murphy´s birthday on the set of Hell´s Island (1955)Any list of noir’s toughest directors would have to include such pugilistic auteurs as Anthony Mann, Robert Aldrich, Richard Fleischer, and Sam Fuller. That said, the toughest noir director of them all might well have been Phil Karlson. He worked his way up from prop man to assistant director, and eventually to director at “Poverty Row” studios that churned out low-budget fare like timber mills spitting out piles of pulp. Karlson’s best film, 99 River Street. John Payne stars as Ernie Driscoll, an ex-boxer turned taxi driver who endures the longest night of his life after his wife dumps him for a jewelry thief. The film is a pitch-perfect example of the Dark Night of the Soul, the noir subgenre wherein a character wrestles with his or her demons over the course of a single treacherous night.

Led by an excellent John Payne, the cast features some of classic noir’s best players: Evelyn Keyes, Peggie Castle, Jack Lambert, and Brad Dexter. In many ways, this film is the ultimate Karlson picture. At its core is the frustration of a man of violence boxed in by situations which keep moving out of his control. Naturally, since this is a Karlson picture, when redemption comes, it comes with a hard right hook. Source: www.criminalelement.com

Led by an excellent John Payne, the cast features some of classic noir’s best players: Evelyn Keyes, Peggie Castle, Jack Lambert, and Brad Dexter. In many ways, this film is the ultimate Karlson picture. At its core is the frustration of a man of violence boxed in by situations which keep moving out of his control. Naturally, since this is a Karlson picture, when redemption comes, it comes with a hard right hook. Source: www.criminalelement.com Ernie Driscoll (John Payne) is a washed-up boxer who was on the verge of becoming champ until he injured his eye in the ring. He's married to the gorgeous Pauline (Peggie Castle), who was hoping for the good life, and now spends her time being angry and disappointed. Unlike most noir heroes, who usually make a bad decision at some point, Ernie is mostly innocent; he never consciously makes a choice to enter the underworld. On the contrary, his dream is to save up enough money to open a gas station! His mistake came years earlier when he confused the adoration of his female fans -- like Pauline -- for the real thing. ("When I was a kid I thought I'd grow up and meet a girl who'd stick in my corner, no matter what. Then I grew up," he says.) Pauline betrays him, his career betrays him, and his own brute strength betrays him. When he loses his temper, he has the power to kill, and thus his assault and battery charge could result in some real, hard time.

Ernie Driscoll (John Payne) is a washed-up boxer who was on the verge of becoming champ until he injured his eye in the ring. He's married to the gorgeous Pauline (Peggie Castle), who was hoping for the good life, and now spends her time being angry and disappointed. Unlike most noir heroes, who usually make a bad decision at some point, Ernie is mostly innocent; he never consciously makes a choice to enter the underworld. On the contrary, his dream is to save up enough money to open a gas station! His mistake came years earlier when he confused the adoration of his female fans -- like Pauline -- for the real thing. ("When I was a kid I thought I'd grow up and meet a girl who'd stick in my corner, no matter what. Then I grew up," he says.) Pauline betrays him, his career betrays him, and his own brute strength betrays him. When he loses his temper, he has the power to kill, and thus his assault and battery charge could result in some real, hard time. Andrew Sarris wrote that one of Karlson's themes was the outbreak of violence in a world controlled by criminals and the corrupt. The film opens on an absolutely astonishing boxing sequence, close-up, ringside and off-kilter, that Martin Scorsese surely studied before he made Raging Bull. Karlson continues this low-angle violence throughout, and even echoes certain key shots over the course of the film. Many small moments further establish his agenda, such as when Rawlins simultaneously takes a belt of liquor and slugs a man in the jaw. In another scene, Linda plays out a lengthy post-murder scene in panicked close-up, with no cuts or cutaways. Source: www.combustiblecelluloid.com

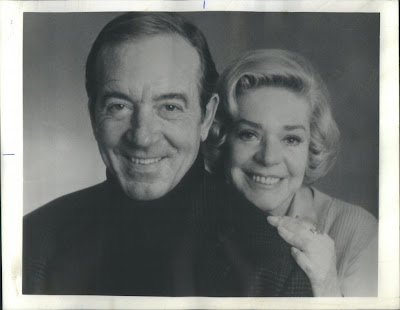

Andrew Sarris wrote that one of Karlson's themes was the outbreak of violence in a world controlled by criminals and the corrupt. The film opens on an absolutely astonishing boxing sequence, close-up, ringside and off-kilter, that Martin Scorsese surely studied before he made Raging Bull. Karlson continues this low-angle violence throughout, and even echoes certain key shots over the course of the film. Many small moments further establish his agenda, such as when Rawlins simultaneously takes a belt of liquor and slugs a man in the jaw. In another scene, Linda plays out a lengthy post-murder scene in panicked close-up, with no cuts or cutaways. Source: www.combustiblecelluloid.com John Payne and Alice Faye in a Press photo for "Good News" (1974)

John Payne and Alice Faye in a Press photo for "Good News" (1974)"Good News" was not designed to win critical acclaim or Tony awards or to dazzle the leading lights of the serious stage. M-G-M filmed the story in the 1940's with Peter Lawford as the quarterback and June Allyson as the student librarian who tutors him. Abe Burrows, who directed the piece, rewrote the book by Laurence Schwab and Buddy de Silva, casting the football coach and the astronomy professor as the romantic leads. Harry Rigby wanted Alice to play the astronomy professor. One factor that led Alice to accept the offer was her costar, whom she handpicked. "I told Harry Rigby, the producer, I'd only do the show if I could have someone I knew-like John Payne-as my co-star," Alice told columnist Douglas Dean. "I hadn't seen him in seventeen years, but I knew we'd work well together. Harry contacted him and when he said yes-well, I was hooked."

The public would be as eager to see John Payne again as they were to see Alice Faye, and the combination would be dynamite. Payne's movie career had effectively ended in 1961, when he stepped out in front of a car in New York traffic. He sustained injuries to his face, which required 150 stitches, and his leg, which was broken in four places. Laid up for months, he gradually healed, but had to teach himself to walk again. Fortunately, his skill as a businessman and some astute real estate investments assured him of a livelihood after the loss of his acting career. "John was a very well-read person and a fine businessman," Alice once stated, the combination once leading him to buy the film rights to a little-known short story called "Miracle on 34th Street." He was, she said, "the least actorish of all the men I worked with." When the company finally did open at the St. James Theatre in New York on December 23, 1974, they did it without John Payne, whose original contract had expired by that time. "His leg hurt a great deal," Alice remembered, "making it very difficult for him to sing and dance and finally just move around on the stage. It wasn't as much fun anymore." -"Alice Faye: A Life Beyond the Silver Screen" (Hollywood Legends) by Jane Lenz Elder (2011)

The public would be as eager to see John Payne again as they were to see Alice Faye, and the combination would be dynamite. Payne's movie career had effectively ended in 1961, when he stepped out in front of a car in New York traffic. He sustained injuries to his face, which required 150 stitches, and his leg, which was broken in four places. Laid up for months, he gradually healed, but had to teach himself to walk again. Fortunately, his skill as a businessman and some astute real estate investments assured him of a livelihood after the loss of his acting career. "John was a very well-read person and a fine businessman," Alice once stated, the combination once leading him to buy the film rights to a little-known short story called "Miracle on 34th Street." He was, she said, "the least actorish of all the men I worked with." When the company finally did open at the St. James Theatre in New York on December 23, 1974, they did it without John Payne, whose original contract had expired by that time. "His leg hurt a great deal," Alice remembered, "making it very difficult for him to sing and dance and finally just move around on the stage. It wasn't as much fun anymore." -"Alice Faye: A Life Beyond the Silver Screen" (Hollywood Legends) by Jane Lenz Elder (2011) In an interview backstage at the Geary Theater in San Francisco, where Payne was co-starring with Alice Faye in the Broadway-bound musical “Good News” he said, “No one thought I would live. I had a fractured skull. My left leg was broken in four places. My chin was literally cut off. There was a question of whether or not the leg would have to be amputated.” Only the proximity of Roosevelt Hotel to the accident saved his life. But the story was not widely reported at the time. To the public, John Payne, mysteriously and suddenly, disappeared. Payne did return to Hollywood but he grew disillusioned with acting, which he called “the hardest-working job in existence.”

In an interview backstage at the Geary Theater in San Francisco, where Payne was co-starring with Alice Faye in the Broadway-bound musical “Good News” he said, “No one thought I would live. I had a fractured skull. My left leg was broken in four places. My chin was literally cut off. There was a question of whether or not the leg would have to be amputated.” Only the proximity of Roosevelt Hotel to the accident saved his life. But the story was not widely reported at the time. To the public, John Payne, mysteriously and suddenly, disappeared. Payne did return to Hollywood but he grew disillusioned with acting, which he called “the hardest-working job in existence.”