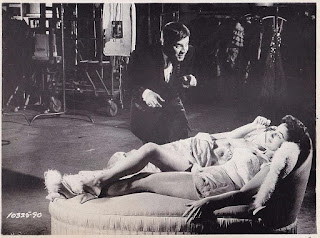

Frank Tashlin made a couple of bizarre films with Jayne Mansfield, who one might argue was a cartoon version of 20th Century Fox’s other zaftig blonde, Marilyn Monroe. Mansfield’s first real success had been in the Broadway version of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? and her part was an explicit parody of Monroe. Her first film with Tashlin at Fox was The Girl Can’t Help It, which includes many early stars of rock and roll, like Fats Domino, Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent. As the critic Dave Kehr pointed out in his article for The New York Times: "The most absurd figure in Tashlin's films is not the heavy-bosomed blonde but the pathetic male in a pure, helpless state of arousal, continually provoked by the eroticized environment that surrounds him." Jayne Mansfield became a living cartoon of nuclear-powered 50’s femininity in “The Girl Can’t Help It”; Jerry Lewis was her polar opposite, a frightened kid trembling on the edge of a hormonal explosion. In 1956 Mansfield and Lewis had appeared together in Las Vegas, posing with a cake at the Sands Hotel's fourth anniversary celebration. Mansfield was beautiful and curvaceous but possessed comic timing and a sympathetic warmth that many other bombshells couldn't--still can't--muster. Tashlin's films have been somewhat neglected in the US, in part because of his close association with Jerry Lewis. “Decades before postmodernism became fashionable, Tashlin was gleefully constructing a world of simulacra and surfaces in which images refer only to other images and characters cobble their identities from mass media and pop culture.” Frank Tashlin died in 1972, but the world he satirized 50 years ago is still with us, in some ways more than ever. Source: www.moviediva.com

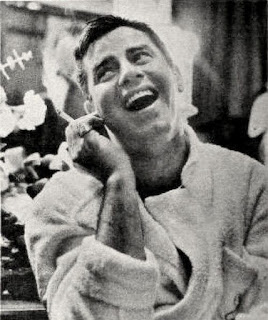

"I remember as a kid, having dreams at nights of becoming a superclown and saving the world from terrible troubles" —Jerry Lewis

Especially as he gained more control over his movies, Jerry Lewis offered up truly schizophrenic characters. An unleashed maniac offering episodes of comedic anarchy as it can barely contain itself is the core character. But Lewis wants you to love this maniac and know he has the soul of a poet. He establishes this with scenes so mawkish that their pumped-up sugar drools out the sides of the screen. On the one hand, he is a force of nature maniacally destructive and sputteringly out of control. The plots of many of the Lewis films are simple: The Bellboy -- Lewis is amok in a hotel; The Ladies' Man -- amok in an all-girls' boarding house; Who's Minding the Store? -- amok in a department store. On the other, he is a tormented soul, a wounded butterfly, a romantic, an emotionally stunted child. Jim Carrey, however, never looks back in his offensive routines. If you've always wondered what it was about Jerry Lewis that sent the French into ecstasy and the loyal fan screaming, check him out in The Disorderly Orderly. If it leaves you cold, venture no further into Lewis land. —Scanlines (1999) by Louis Black for The Austin Chronicle

Jerry Lewis was a challenging and enigmatic figure long before the French got their hands on him. Although the merits of Jerry Lewis's self-directed films have been hotly debated, comparatively little attention has been paid to the highly successful 1950s films that made possible his move into film directing. Lewis first met Dean Martin in August 1944 when they were signed as individual attractions at New York's Glass Hat Club. Martin was the headliner, while Lewis played his record act and served as master of ceremonies. That's My Boy (1951) had a serious-minded story that anticipates such melodramas of masculine crisis as Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Tea and Sympathy (1956), and Home from the Hill (1960). The film's plot deals with questions of how to be a man, and how to be a man among men, with Lewis playing a characteristic psychoneurotic cowed by a hyper-athletic father but finding solace in the sheltering embrace of Martin's gentle buddy. The Stooge (1952) offers the most dramatically sustained exploration of the two-man relationship, with its intermingling of affection and hostility, togetherness and difference. The promise of their union coexisted with a strong awareness that the competition between the two men, and between their distinctive talents, always threatened to rend the partnership asunder. News of Dean Martin's dissatisfaction began to filter into the public arena during the troubled production of 3 Ring Circus. Lewis reported: "During the filming Dean kept blowing his top at me and everyone else, saying he was fed up to the ears playing a stooge.... It developed into psychological warfare for the balance of the picture". Their partnership was clearly on a downward spiral. Reported schisms and rumor-mongering made it difficult for audiences to believe that their freewheeling, fun-loving act was grounded in authentic feeling.

The Spring 2018 FILMS OF THE GOLDEN AGE is out! Articles: The Five Lane Sisters, Jerry Lewis Part I (by Charles Tranberg), James Mason, Kaye Ballard, Tom Tyler, SHANE (1953), SECRETS OF THE FRENCH POLICE (1932), and the regular feature OVERLOOKED IN HOLLYWOOD (profiles on Lester Vail, Mary Nolan, Lewis Wilson, Peggy Conklin, Rebel Randall, and Paul Page). Charles Tranberg: People might have found Dean Martin more handsome but I would say that is probably true that Jerry Lewis was "cuter." Ironically, despite of Martin being the official heartthrob of the duo, Shawn Levy hints in The King of Comedy (1997) that Jerry Lewis had the most active sexual life, since Martin's seduction game often worked on a superficial level. Lewis himself had confessed to Levy: "I never could stay mad at women, because I had a high sex drive."

When the end came in 1956 the masquerade was over. While he could win over popular audiences, the new Jerry Lewis who rose with such untimely haste from the ashes of the beloved entertainment team met with a remarkably hostile reception from cultural tastemakers. Attacks on his aspirations and abilities were to become commonplace in the press long before "the French" staked their claim to him. The opposition grew more vocal as Lewis explored territories barred to the simple funnyman of old. By the end of the decade he was not just one of the best beloved of American entertainers; he was also just about the most reviled. Films such as The Caddy, Scared Stiff, The Stooge, and Living It Up had teased with the Lewis figure's status as a harassed misfit, but the team's partnership dynamic had always trammeled the poignancy. Unshackled from his quarrelsome partner, Lewis was free to use his familiar Idiot/Kid figure to develop a more extended treatment of the comic misfit as a beleaguered outcast questing for acceptance. Lewis contextualized the traumatic breakup of Martin within a bionarrative of abandonment that stretched back to his lonely childhood. Lewis fleshed out this biographical narrative in an article by journalist Bill Davidson: "I've Always Been Scared," shortly after the partnership folded, in February 1957. This article exposed a bruised sensitivity cowering in the shadow of the manic clown. "All my life," Lewis declares, "I've been afraid of being alone". In a story he would repeat, Lewis portrays himself as a pathetic outsider who deploys the mask of comedy as a protective shield. Seeking love and acceptance via the showbiz success his father never attained, Lewis is compelled to win the substitute gratifications of applause and laughter: "If I could make people laugh, I thought, they'd like me and let me be with them".

The psychological narrative articulated by these articles highlights the degree to which Lewis's star image occupied a very different constellation from the carefree zany of old. Whereas earlier publicity stressed the congruence between the onstage and offstage selves of Martin and Lewis, Lewis's solo career instituted a strategic opposition between the "real" man alone and the onscreen comic misfit. "It may be," offers Look magazine, "that audiences are drawn to him because they see or sense the real Jerry, the lonely man of many complexes" ("Always in a Crowd-Always Alone," 1958). The director of six Martin and Lewis pictures and two of Lewis's solo films Norman Taurog told Arthur Marx: "In the beginning, he was a doll. He listened, did what I told him, and didn't bother anyone. Then one day I noticed him looking through the camera between takes and starting to make suggestions to Lyle Gregg, our cameraman, on things he had no business making suggestions about: how high a crane to put the camera on, or what kind of lens to use.... I used to tell him, 'For God's sake, Jerry, why do you want to waste your energy doing things other people are getting paid for? Nobody goes to a Martin and Lewis movie because you directed a scene. They go because it says on the marquee-Jerry Lewis in so and so; not Jerry Lewis, cameraman. Save your energy for acting'."

The Delicate Delinquent flaunts Lewis's allegiance to the youth audience. At the same time, it also distances him from the energetic and rebellious excess that marked his earlier performances. Rather than abandoning himself to the delights of sheer abandon, Lewis's delicate delinquent, Sydney Pythias, is searching (literally) for direction. Mistaken for a gang member after a street rumble, the good natured orphan is hauled off to the neighborhood precinct house, where he encounters patrolman Mike Damon (McGavin). A reformed juvenile offender himself, Damon has a mission to save slum kids from criminal temptations. Sydney is perfect for such rehabilitation as he lacks social and familial ties, or any other external context of self-definition. "How does a guy know what he wants to be?" he asks Damon. "Especially somebody like me? I'll tell you what I am-I'm a nowhere." Sydney's eventual success suggests that a good heart will eventually triumph over insecurity and sheer ineptitude. For Bosley Crowther, Sydney's characteristically Lewisian eccentricities sat rather uncomfortably with the idealized authority he is allowed at the end of this "serious-message comedy": "Mr. Lewis runs a gamut from Hamlet to clown. Mr. Lewis, trying to act hard like a man, trying to fit odd-shaped blocks into odd-shaped holes, is a delirious comedian. The good intention of his message may be missed in this eccentricity."

Robert Kass suggested in Films in Review that Lewis emblematized the otherness of "young America gone berserk". From a more celebratory perspective, J. Hoberman proposes that "the young Jerry was America's id. His every cute outburst threatened to escalate into loss of control; the sight of his big mouth promised a kind of ecstatic self-annihilation" ("The Nutty Retrospective," Village Voice, 15 December 1988). The uncontrolled eruptions of Lewis's body connected with the rebellious stirrings of a nascent youth culture, which would itself erupt into national and international consciousness with the primal beat of rock 'n' roll. As Karal Ann Marling argues, "Like Elvis, Jerry Lewis seemed rebellious because he wouldn't stand still; he both projected and aroused strong emotion through motion". —Larger Than Life / Movie Stars of the 1950s: Jerry Lewis (2010) by Frank Krutnik