Life and Death on Breaking Bad by Jonah Goldberg — When we first meet Walter White, he is an overqualified high-school chemistry teacher who works part time at a car wash for extra money. (In what becomes a crucial plot device, Walter worked for a tech startup but took a stupid buyout for $5,000. The company went on to be worth billions.) In the first 20 minutes of the first episode, he is diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Impeccably decent and upright, Walter is confronted with the horror of leaving his wife, teenage son (who has cerebral palsy), and unborn daughter destitute. He gets the idea that he could use his skills as a scientist to cook methamphetamine (crystal meth). The once-promising professional (The Dr. Jekyll of Walter White) slowly turns into the Mr. Hyde of his street name “Heisenberg” (an homage to the author of the uncertainty principle). When we meet him, Walter White is not an antihero; he’s even a hero in the small ways good fathers, dedicated teachers, and faithful husbands are. And what he becomes is not an antihero but simply, straightforwardly, a villain. What begins as a kind of play on the Thomistic principle that it is moral for a man to steal bread to feed his starving child grows into a painfully realistic tale of how a good man becomes evil.

Over time, Walter’s definition of self-defense grows beyond any moral justification, and his reluctance to kill shrinks to almost nothing. Once you step outside the borders of morality and the law, self-interest becomes self-justifying. Indeed, this is how pragmatism unchained from moral principles simply becomes a Nietzschean will to power. But the choices Walter makes have tragic consequences. The lies he needs to tell to his wife, Skyler, ultimately destroy his marriage. She cannot abide the deception, and when she finds out about Walter’s new profession, she wants a divorce. This plotline is absolutely brutal to watch and is easily the best treatment of a family coming unglued in any television show. Skyler, too, finally becomes seduced into Walter’s world. Personal corruption is infectious. What the viewer has only dimly suspected, thanks to Cranston’s incredibly subtle portrait, is now coming to the fore: Walter enjoys being Heisenberg.

One of the reasons he enjoys it is that, unlike the underachieving high-school chemistry teacher of his former life, Heisenberg is the best there is at something. While he could once live with the fact that his former peers have gotten rich in the private sector (off his ideas, he tells himself), it is now a source of seething resentment. The sins of pride and envy—rather than greed—are the secrets to Walter White’s character. The arrogance of Walter’s intellect, married to the bitterness of not fulfilling his potential, seduce him to the idea that he can set the rules, that he is smart enough to control all of the variables in life. Untethered from traditional morality, he’s set adrift, believing that he can chart his own course through raw intellect alone. Actually, the money is meaningless to him save as a measure of his ability and superiority. Gilligan and the other writers brilliantly draw out how envy of the success of others fuels a sense of superiority and entitlement. In one telling scene, White tells his students the (true) story of how the inventor of the synthetic diamond was rewarded by GE with a $10 bond. The subtext is that Walter never got the recognition he deserved as a scientist, and he yearns to correct that as an illegal meth cooker.

“I just feel like I never had a choice in any of this,” he explains. “I want a say, for once.” As Jackson Cuidon writes, “When you first watch the scene, not knowing the kind of person Walt is going to choose to be, it’s a poignant moment. Walt wants to spend his last months with his wife on his own terms, rather than as a powerless and weak and hollowed-out shell of who he used to be.” When Walter says this in the first season, he means it. The problem is that, over time, he takes this desire for control over his own life and externalizes it to society. His response to cancer transforms him into a cancer in his family and in his community. Cuidon is entirely right that the essence of Breaking Bad is choice: Walter chooses to become evil. Breaking Bad is not a religious allegory (though it could be seen as one). The lies Walter hears are not coming from the Devil, they’re coming from Walter himself. (Gilligan has said that while he can believe there’s no Heaven, he can’t abide by the idea there’s no Hell.) An even more striking aspect of Breaking Bad is the omnipresent backdrop of the horrors of drug addiction. Meth is particularly evil, ravaging not just addicts but whole communities. Walter becomes evil as he rationalizes away that fact.

And here is where I think Gilligan himself has it wrong. “Walt has behaved at times in what could be regarded as an evil fashion, but I don’t think he’s an evil man,” he told the website Vulture. “He is an extremely self-deluded man. We always say in the writers’ room, if Walter White has a true superpower, it’s not his knowledge of chemistry or his intellect, it’s his ability to lie to himself.” But what is evil if not the ability to delude yourself into believing you are the sole arbiter of what is right and wrong based on your self-interest? Freedom itself is not evil, but freedom devoid of conscience is very close to the definition of evil. Hitler, Stalin—the historical figures we use as stand-ins for metaphysical evil—believed they were acting on their own personal definitions of the good. They didn’t feel constrained by the “slave morality” (Nietzsche’s term) of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Of the many conservative themes in Breaking Bad, the one I appreciate most is the fragility of civilization: Preserving it requires a constant struggle. When I say “civilization,” I don’t mean just the particular swath of time and culture we call “Western Civ”; I mean families, communities, and individuals. These can be healthy only when individuals are willing to take on faith that some moral laws are there for a good reason. As G. K. Chesterton tells us, pure reason doesn’t get humanity very far. The merely rational man will not make commitments to causes greater than his own self-interest.

We need binding dogmas to constrain us even when our intellects or appetites try to seduce us to a different path. Long before one gets into the partisan or ideological precepts and dogmas, there is at the irreducible core of conservatism the idea that human nature is what it is. Nation-states, technologies, cultures, even religions come and go, but what always remains is humanity. Breaking Bad is one of those special stories from a great novel because it grapples with the crooked timber of humanity as it is, and painfully demonstrates that, once you choose to break out of the cage of civilization, you are not so much free as you are lost. Source: www.nationalreview.com

Our moral expectations in the world of art differ from our expectations in the real world around us. The people we are at work, at the grocery store, play by one set of largely artificial rules: the rules of civilization. But beneath—or perhaps beside—the person of manners, custom, and law resides a different being. The moral universe of cinema sometimes mirrors the real world, but just as often the actors on the screen play roles more consistent with the moral universe of our inner savage. It’s like a scene in some science fiction movie where the protagonist develops a roll of film and finds that the people he photographed are different from those he saw with his naked eye. Art captures a reality that we tend to deny in the “real world” around us. In novels, movies, TV, video games, and almost every other realm of our shared culture, the moral language of the narrative is in an almost entirely different dialect from the moral language of the larger society. When we suspend disbelief, we also suspend adherence to the conventions and legalisms of the outside world. Instead, we use the more primitive parts of our brains, which understand right and wrong as questions of “us” and “them.” Our myths are still with us on the silver screen, and they appeal to our sense of tribal justice. We enter the movie theater a citizen of this world, but when we sit down, we become denizens of the spiritual jungle, where our morality becomes tribal the moment the lights go out. When we lose our civilizational confidence—and pride—in what it has accomplished, we are committing a suicidal act on a civilizational scale. —"Suicide of the West" (2018) by Jonah Goldberg

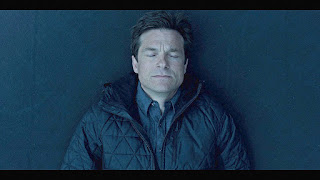

Martin 'Marty' Byrde (Jason Bateman in Ozark): If I want to put all $7,945,400 into a hot tub, get buck naked and play Scrooge McDuck, that is 100% my business. You see, the hard reality is how much money we accumulate in life is not a function of who's president or the economy or bubbles bursting or bad breaks or bosses. It's about the American work ethic. The one that made us the greatest country on Earth. It's about bucking the media's opinion as to what constitutes a good parent. Deciding to miss the ball game, the play, the concert, because you've resolved to work and invest in your family's future. And taking responsibility for the consequences of those actions. Patience. Frugality. Sacrifice. When you boil it down, what do those three things have in common? Those are choices. Money is not peace of mind. Money's not happiness. Money is, at its essence, that measure of a man's choices. Half of all American adults have more credit card debt than savings. 25% have no savings at all. And only 15% of the population is on track to fund even one year of retirement. Suggesting what? The middle class is evaporating? Or the American Dream is dead? You wouldn't be sitting there listening to me if the latter were true. You see, I think most people just have a fundamentally flawed view of money. Is it simply an agreed-upon unit of exchange for goods and services? $3.70 for a gallon of milk? Thirty bucks to cut your grass? Or, is it an intangible? Security or happiness - peace of mind.

“The question of whether America is in decline cannot be answered yes or no. Both answers are wrong, because the assumption that somehow there exists some predetermined inevitable trajectory, the result of uncontrollable external forces, is wrong. Nothing is inevitable. Nothing is written. For America today, decline is not a condition. Decline is a choice.” —Charles Krauthamer (1950-2018)

No comments :

Post a Comment