James Stewart as Ransom Stoddard in "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" (1962) directed by John Ford

James Stewart as Ransom Stoddard in "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" (1962) directed by John FordVery little published work has specifically addressed the relationship between masculinity and film performance. Two key book length studies include Steven Cohan’s "Masked Men: Masculinity and the Movies in the Fifties" and Dennis Bingham’s "Acting Male: Masculinities in the Films of James Stewart, Jack Nicholson and Clint Eastwood".

Bingham’s "Acting Male" is closer to a ‘star study’ of three actor case studies - Robert Sklar’s "City Boys: Cagney, Bogart, Garfield" is similar in this regard.

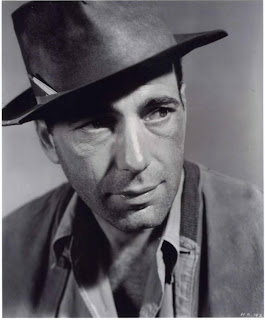

Bingham’s "Acting Male" is closer to a ‘star study’ of three actor case studies - Robert Sklar’s "City Boys: Cagney, Bogart, Garfield" is similar in this regard. John Garfield as Tony Fenner in "We Were Strangers" (1949) directed by John Houston

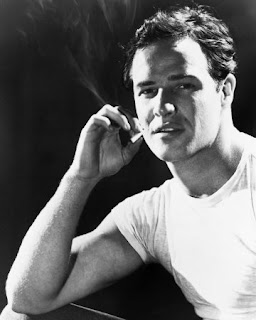

John Garfield as Tony Fenner in "We Were Strangers" (1949) directed by John HoustonRobert Sklar takes smoldering Method-actor Garfield's later roles in "Force of Evil" and "We Were Strangers" and finds them wanting in "psychological dimension -the sense that what was being communicated through repression was a complex inner life" which at that time was forcefully communicated by up-and-coming Method actors Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando.

Humphrey Bogart as Paul Fabrini in "They drive by night" (1940) directed by Raoul Walsh

Humphrey Bogart as Paul Fabrini in "They drive by night" (1940) directed by Raoul WalshFollowing Bogart's acting style from juvenile to heavy to his restrained humors as romantic hero, then to comic actor ("The African Queen") and to later tries at widening his image, Sklar skillfully contrasts the star's two portraits of paranoid characters, Fred C. Dobbs in "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre" and Captain Queeg in "The Caine Mutiny", and finds the much- praised Queeg far less complex or convincing than Dobbs, and in fact excruciating.

And Cagney "does not merely inhabit or present [the figure of Tom Bowers in The Public Enemy]...he creates it...His short, quick movements, his clipped diction, his mobile eyes and mouth, are counterpointed with...an almost sultry languor". -Kirkus Reviews.

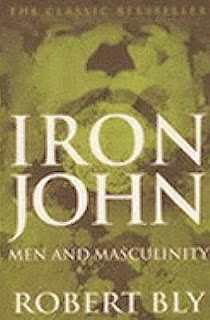

And Cagney "does not merely inhabit or present [the figure of Tom Bowers in The Public Enemy]...he creates it...His short, quick movements, his clipped diction, his mobile eyes and mouth, are counterpointed with...an almost sultry languor". -Kirkus Reviews. Robert Bly’s "Iron John: A Book About Men" is noteworthy for its engagement with the idea of masculinity as a collective and communal practice. Bly admires the stoicism of the ‘fifties male’, bemoans the feminine ‘soft male’ of the 1970s and calls for men to uncover the ‘deep’ masculinity inherent in all men than has been hidden as a result of social and cultural changes of the past few decades, articularly feminism. In this way, Bly’s work appears to conform to a wider pattern in film and masculinity studies in seeing masculinity as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’.

Robert Bly’s "Iron John: A Book About Men" is noteworthy for its engagement with the idea of masculinity as a collective and communal practice. Bly admires the stoicism of the ‘fifties male’, bemoans the feminine ‘soft male’ of the 1970s and calls for men to uncover the ‘deep’ masculinity inherent in all men than has been hidden as a result of social and cultural changes of the past few decades, articularly feminism. In this way, Bly’s work appears to conform to a wider pattern in film and masculinity studies in seeing masculinity as either ‘hard’ or ‘soft’. Social historians such as Michael Kimmel have attempted to locate crises of masculinity historically, quantifying them schematically according to dominant social positions such as ‘profeminist, antifeminist, and promale’. Kimmel defines crises of masculinity as cultural and historical ‘moments of gender confusion that assume a prominent position in the public consciousness’, offering examples in Restoration England (1688–1714) and the US in the years 1880 to 1914.

Social historians such as Michael Kimmel have attempted to locate crises of masculinity historically, quantifying them schematically according to dominant social positions such as ‘profeminist, antifeminist, and promale’. Kimmel defines crises of masculinity as cultural and historical ‘moments of gender confusion that assume a prominent position in the public consciousness’, offering examples in Restoration England (1688–1714) and the US in the years 1880 to 1914. Harrison Ford as Henry Turner in "Regarding Henry" (1991) directed by Mike Nichols

Harrison Ford as Henry Turner in "Regarding Henry" (1991) directed by Mike NicholsSimilarly, Fred Pfeil suggests the 1990s signalled a shift in masculine subjectivity towards a more sensitive, domesticated male, as performed by Harrison Ford in "Regarding Henry" (1991) or Arnold Schwarzenegger in "Kindergarten Cop" (1990). Pfeil terms 1991 ‘The Year of Living Sensitively’ and suggests such representations offer a direct contrast to the ‘rampagers’ of the "Lethal Weapon" (1987 and 1989) and "Die Hard" (1988) films from the previous decade. Jonathan Rutherford has even gone so far as to categorise supposedly conflicting masculine identities as the ‘New Man’ and ‘Retributive Man’. The New Man is ‘an expression of the repressed body of masculinity. It is a response to the structural changes of the past decade and specifically to the assertiveness and feminism of women’.

Ultimately, these position pieces argue that the masculine tropes described emerge from a critical convergence of events shaping masculine identities during specified periods. Masculinity, as scholars such as R. W. Connell have pointed out, is a fluid identity and constantly in flux. Since what constitutes ‘being a man’ continually changes according to the particular social or cultural moment, adapt, change and, in effect, recycle their male identities. Yet movement too far in either direction is considered to undermine masculinity.

Ultimately, these position pieces argue that the masculine tropes described emerge from a critical convergence of events shaping masculine identities during specified periods. Masculinity, as scholars such as R. W. Connell have pointed out, is a fluid identity and constantly in flux. Since what constitutes ‘being a man’ continually changes according to the particular social or cultural moment, adapt, change and, in effect, recycle their male identities. Yet movement too far in either direction is considered to undermine masculinity. Edward Norton and Brad Pitt as The Narrator and Taylor Durden in "Fight Club" (1999) directed by David Fincher

Edward Norton and Brad Pitt as The Narrator and Taylor Durden in "Fight Club" (1999) directed by David FincherThe excessive, performative nature of the 'Wild Man' has been explored in numerous literary and cinematic examples but arguably most prominently in Chuck Palahniuk’s 1996 novel, "Fight Club", and via the ‘excess and absurdity’ of the 1999 film version starring Brad Pitt as 'Wild Man' Tyler Durden. The novel and film have received an extraordinary amount of critical and academic attention, mostly focusing on the portrayal of destructive, misogynist masculinity.

Although Palahniuk said in interviews that he had not read "Iron John", Tyler and Jack (played by Edward Norton in the film) could have been lifted from its pages, resonating themes of father loss and overdependence on the mother, initiation ceremonies (head shaving), and the supposedly feminising effects of consumer culture.

Although Palahniuk said in interviews that he had not read "Iron John", Tyler and Jack (played by Edward Norton in the film) could have been lifted from its pages, resonating themes of father loss and overdependence on the mother, initiation ceremonies (head shaving), and the supposedly feminising effects of consumer culture. Jack moves into Tyler’s dilapidated house and they start an underground boxing club to give men the opportunity to release their primal aggression and reclaim their sense of masculinity. When the fight clubs become a national success, Tyler decides to ‘take it up a notch’ and Project Mayhem is born: a full-scale anti-capitalist terrorist organisation with the ultimate aim of overthrowing corporate America and eradicating consumer debt.

Jack moves into Tyler’s dilapidated house and they start an underground boxing club to give men the opportunity to release their primal aggression and reclaim their sense of masculinity. When the fight clubs become a national success, Tyler decides to ‘take it up a notch’ and Project Mayhem is born: a full-scale anti-capitalist terrorist organisation with the ultimate aim of overthrowing corporate America and eradicating consumer debt. However, women are ultimately more threatening to men than consumerism and Tyler’s misogyny culminates in his verbal and emotional response to Marla (Helena Bonham Carter); women are ‘tumours’, ‘scratches on the roof of your mouth’, and ‘predators posing as house pets’.

However, women are ultimately more threatening to men than consumerism and Tyler’s misogyny culminates in his verbal and emotional response to Marla (Helena Bonham Carter); women are ‘tumours’, ‘scratches on the roof of your mouth’, and ‘predators posing as house pets’. At the same time, in labelling herself as ‘infectious waste’, Marla corroborates the image of women as dirty and contaminated, further reinforced by Tyler’s donning of rubber gloves during a sexual encounter.

At the same time, in labelling herself as ‘infectious waste’, Marla corroborates the image of women as dirty and contaminated, further reinforced by Tyler’s donning of rubber gloves during a sexual encounter. Representations of the 'Wild Man' in "Fight Club" explicitly model themselves in opposition to the figure of the 'Wimp'. Tyler Durden’s 'Wild Man' is repeatedly set against Jack, whose softness is amplified when framed in conjunction with Tyler’s hypermasculinity. "Fight Club" demonstrates a self-conscious awareness of this opposition by playing with the conventions of masculinity and femininity. -"Masculinity and Film Performance: Male Angst in Contemporary American Cinema" by Donna Peberdy (2011)

Representations of the 'Wild Man' in "Fight Club" explicitly model themselves in opposition to the figure of the 'Wimp'. Tyler Durden’s 'Wild Man' is repeatedly set against Jack, whose softness is amplified when framed in conjunction with Tyler’s hypermasculinity. "Fight Club" demonstrates a self-conscious awareness of this opposition by playing with the conventions of masculinity and femininity. -"Masculinity and Film Performance: Male Angst in Contemporary American Cinema" by Donna Peberdy (2011)

No comments :

Post a Comment